Terrie L. Pendleton: Cofounder, Lesbian Women of Color

Terrie Pendleton founded Lesbian Women of Color in Richmond, VA, in 1991 to provide “a sense of belonging, a safe place,” an alternative to isolation.

Edited for the web by Merril Mushroom. Interview by Rose Norman, January 16, 2016.

Terrie L. Pendleton: I was born June 5, 1956, to a 17-year-old mother and a father in the military, who were not married. I grew up in the small town of Ardmore, Pennsylvania, which is just outside of Philadelphia and on the main line in an upscale area. But my neighborhood, my African American community, was on the outskirts of this upscale area. I suppose families who were somewhat affluent lived in Ardmore.

My grandmother, Marjorie Pendleton, was the first African American, registered nurse in that area. She was very well known to both white and African Americans for her outspoken dedication to people of color and to her church, Mount Calvary Baptist Church. I am the oldest of four children and grew up pretty traditionally African American. I went to school in an all-Black community and school until integration, when we were bused to a white school called Penn Wynne Elementary School when I was in 4th or 5th grade. It was interesting and strange to leave your community of African American teachers, African American mentors, and people that look like you to go to a school where people didn’t look you. I think that people of color have always understood the transition or the issue of going in and out of different communities. Although it was strange, we learned how to act and how to be in that community, the integrated community; and we learned who we were, who we really are, in our own community. I don’t remember it being stressful at all or very hard. It was not that way for me. My sisters were really close to me, and we were able to navigate that system well, I think.

Biographical Note

Terrie L. Pendleton, born June 5, 1956, grew up in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. She joined the Army and served from 1977 to 1980. She lived in Germany from 1980 to 1985, when she moved to Virginia with her then partner, a woman she had met in the military. She moved to Richmond, Virginia in 1987. In Richmond, she earned a bachelor’s degree from Virginia Commonwealth University, and she earned a master’s in social work to become a licensed, clinical social worker, a profession she has practiced there ever since.

I came to Richmond in 1985 with a partner I had met in the military. We had been together for ten years. I joined the military in 1977, completing basic training at Fort McLellan, AL; going to Fort Lee, VA, for my educational training; and then going to Fort Campbell, KY, where I met the woman who was my partner for ten years. We went overseas to Germany. We had a holy union in Nashville, TN, prior to leaving for Germany in 1979. I got out of the military in 1980, came back to the states to discharge from the military, and went back to Germany to stay there with my partner for another four or five years. We came to Virginia in 1985, stationed at Fort Lee.

At that point, my relationship with that partner broke up. In about 1987, I moved to Richmond from Petersburg, VA, thirty minutes south of Richmond down [interstate highway] I-95. At that point, I identified as a lesbian, and I wanted to know where all the African American lesbians were in Richmond. I could not seem to locate them. I thought, “how odd!”

TP: Having been here [in Richmond] since 1987, I do now identify myself as a Southerner. Even though I don’t like to play in the dirt, I like the Southern way of living, the food, the hospitality, the people. I like being in the South and probably would move further South when the time comes. I’m partnered again for 23 years now with a woman I love very much. We have not decided to marry legally yet. We couldn’t believe it that this would come in our lifetime, so we hadn’t thought about it. We’re thinking about it now.

My gosh, I am a feminist and an activist, and a woman who thinks very clearly about the identification of race and gender and sexuality.

TP: I’ve always thought of myself as a feminist. I didn’t have those words until I started school down here at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College [in Richmond], and then Virginia Commonwealth University for a bachelor’s degree in general studies/minority resource services, and a minor in women’s studies and psychology. That is when I realized that my gosh, I am a feminist and an activist, and a woman who thinks very clearly about the identification of race and gender and sexuality.

The issue of being African American and a lesbian in a community of color is very different from being a lesbian in the mainstream culture. Of course, there are going to be many different stories and ways to look at it, and many different ways that people grow up. For me, my lesbianism started before I joined the military. I had a love affair with a woman in my community, and she was older than I was. I really didn’t understand lesbianism as a construct, but I knew that I was attracted to her, I loved her, and I cared for her very much. I was a product of a matriarchal household. I lived with my grandmother, my mother, and an aunt in a home that my grandmother bought. Seeing my grandmother as a very strong African American woman, of course, I had no doubt in my mind that I was the same way, and that I could do whatever I wanted. I could be whoever I wanted. Being from that household really did build my character and who I was to be: a very strong person in my own right. So, lesbianism came into my life way before I understood it per se. I had a relationship with that woman before going into the military. I was still trying to understand my sexuality with men, but it really was not something that I was interested in doing. I think I dabbled in relationships with men until I got into the military because it was normal, it was what I knew. When I joined the military, I realized I didn’t have to do that.

I decided that I was going to find lesbians of color; and I was going to try to figure out what they wanted and what their lives were about… and what they would like to be involved with.

TP: Here in Virginia I wondered where the African American women were, and why I didn’t see them at the only lesbian bar I knew, Babe’s on Terry St. I had a few friends, and I asked them, “Where are all the women of color, and why aren’t they present at meetings of Richmond Lesbian Feminists? Do they see themselves as feminists? How do they view themselves?” I decided that I was going to find lesbians of color; and I was going to try to figure out what they wanted and what their lives were about… and what they would like to be involved with.

In 1991, I put an ad in Style Weekly magazine, still in production today, a very progressive magazine here in Richmond, where you could put ads. I pretty much said something like “lesbians of color, where are you? I would like to meet you for friendships, getting to know each other, and sharing thoughts and ideas.”

Our dictum is that in spite of an oppressive society, we as women-loving-women who are of color can organize a diverse group that will allow us to examine avenues of empowerment.

I have some writings we did. Here is one of the things that came out of it [reading]:

The Lesbian Women of Color was founded in 1991 to primarily address and respond to the question, “Where are the Black lesbians in Richmond?” and “What does the community have to offer Black lesbians?” In the ensuing dialogue, we realized that if the community was lacking in activities, it was because we were not visible; nor, had we acknowledged our needs. In addition, we as Lesbians of color were not putting forth efforts to address our concerns.

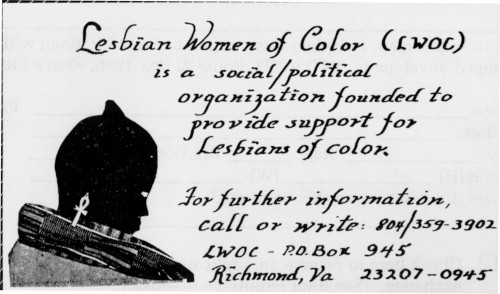

Lesbian Women of Color (LWOC) is a progressive, social, cultural, and political organization that addresses the needs and concerns of African American lesbians and other lesbians of color who acknowledge and identify culturally, socially, and psychologically with an ethnic group or race that is non-Anglo in origin.

The founding members felt very strongly about the need to encourage lesbians of color to express their feelings and needs as related to living in a society that relates negatively to us as women (sexism), lesbians (homophobia) and as people of color (racism). The wounds of these societal scars run deep. Our vision is to provide lesbians of color with a sense of belonging, a safe place to express anger and frustration; and to provide alternatives to loneliness & isolation.

Our dictum is that in spite of an oppressive society, we as women-loving-women who are of color can organize a diverse group that will allow us to examine avenues of empowerment.

Other goals consist of planning social events, political events, and cultural events. A major long-range goal is to open and own a space that is operated by lesbians of color. The space will function as a social, cultural, and recreational center. The Lesbian Women of Color encourages inquiries about our group. Group coordinator Terrie Pendleton can provide more information. Please contact her at [phone], or contact group number at Lisa [phone number].

The LWOC expresses sincere thanks to the Richmond Lesbian Feminist staff for their statement of support. A special thanks to Beth Marschak for her wisdom and encouragement.

This was one statement sent out to the universe. This was not the ad. I think it was a statement we put in the Richmond Lesbian Feminist newsletter, and came out a little later than the ad. That ad garnered so many calls to my number that it was unbelievable, lesbians of color coming out of the woodwork. From that ad, we had several meetings at my small apartment in the Fan [historic downtown district of Richmond]. We began to organize.

I have another letter here that we wrote:

“Dear Sister, Greetings from the Lesbian Women of Color! This short letter is to introduce you to our organization, and to invite you to explore the possibilities of affiliation with L.W.O.C. Enclosed you will find a copy of our Mission Statement, a Calendar of Events, and a special invitation to join us April 5, 1992, for a Potluck Social Evening at Fieldens. The L.W.O.C. is in its first year of existence, and we are looking to encouraging participation and support from positive women. In order to support our women, discretion and confidentiality are strongly observed. Hoping to hear from you!”

TP: So, we started meeting monthly at my apartment, reaching out to other lesbians of color, and putting out a monthly newsletter. There was a core team that included Robyn Troublefield and Lisa Boone-Wadji,[1] and it just kind of flew off. Robyn Troublefield was very instrumental in putting out the newsletter.

Out of LWOC came excitement in Richmond among lesbians of color about who we were, about political involvement, and I realized that the sisters had not… When you are a minority of any kind, and being a lesbian, of course, makes you marginalized, you identify so much with, well, in those days, I identified so much with being connected to something, having a will to grow something, having a desire to make something happen. My desire was so strong that I think sometimes, I was very misunderstood. Words like “aggressive” and “bossy,” things like that, I think that women attributed to me. Yet, in my mind it was just a passion and a desire to bring women of color together, and to say, “Hey, Richmond, you have been a part of our ostracism and a part of our being marginalized. And we are no longer going to allow that to happen.”

The women who became the core group of LWOC, probably four to eight people, had the same amount of passion that I had. We really worked very hard at putting things together. We began organizing by reaching out to other lesbians of color and putting together events. I have a handwritten flyer for an event held April 5, 1992.

Dr. Judith Bradford is a lesbian, not a woman of color, who ran a very large department at Virginia Commonwealth University. She was involved in or was the lead on the National Lesbian Health Care Survey. I went to VCU, so I knew many people that I met there; and Dr. Bradford was one of the people who mentored me. She agreed to come on April 5, 1992, at Fieldens, a main social, party place, a very large hall, where predominately gay men met after hours. You had to know somebody to get in there. They loaned us the space, and we had the potluck, and Dr. Bradford came. It was quite an event for lesbian women of color and white women from Richmond Lesbian Feminists who knew Dr. Bradford. I think it was one of the first events that drew such a large crowd of women from the different cultures together. The LGBT community in Richmond was very segregated, very segregated in the late 1980s and early ‘90s. It was unbelievable. That’s my remembrance of it.

We also had movies like Thelma and Louise. We tried to make women of color aware of what was going on in their world. I think Black women, and Black people who were gay, felt they weren’t involving themselves in this larger, predominately white, gay rights struggle because “what they hell have they ever done for us?” That was kind of the word I was getting from the women who were part of the LWOC community. They felt the white community had never reached out to them.

One of the things that happened was that Beth Marschak and I grew to be very good friends, and we are still are friends today. We worked very diligently to bring white lesbians and African American lesbians, or lesbians of color, together during that time. We tried to collaborate more and to see what the distance was all about.

Urvashi Vaid was the executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force at that time. The University of Virginia’s Bisexual and Gay organization brought her to Virginia. LWOC pulled together carpooling for women of color to go to Charlottesville for the free lecture on March 25, 1992. I’m looking at a flyer saying, “Join the Lesbian Women of Color to celebrate the University of Virginia’s Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Awareness Day. We will be carpooling to hear Vaid, and afterward, going a new club, Triangles. The lecture is free at UVA’s Newcomb Hall.” That’s an example of the kinds of things we did. We would find out what was going on politically and socially in our community, and we would make it known to lesbians of color.

Here’s another one: “Lesbian Women of Color invite you to an evening out [April 25, 1992], a time to socialize with members and relax. Meet at Metropolis [another gay club] at 8 pm. Bring a friend.” We did things like that.

Here is the mission statement:[2]

Lesbian Women of Color is a Social/Political organization founded to provide support for Lesbian Women of Color. Our goal is to develop sisterhood and to create a network of Lesbian Women of Color by:

*Sharing life experiences relating to Racism and Exclusion Bringing about unification of Lesbian Women of Color

*Exploring Multi-cultural connections through music, traditions, rituals, food, dance, art, and literature.

*Educating ourselves and others outside the community regarding issues that pertain to the Lesbian community

*Sharing feelings about personal issues.

The interest of the L.W.O.C includes: Supporting charitable organizations, lecture presentations, women’s workshops, and planned social activities.

TP: After we had met for quite a lot of times, an Asian woman came to a meeting saying that she wanted white women to be able to come to the group meetings. That caused quite an uproar. It was unbelievable. She wanted white women to come to the meetings, and she could not understand why we needed this group to be solely for women of color. Quite a bit of controversy was going on there. The women at this particular meeting were adamant that the group was not trying to be prejudiced against white women. We tried to help this woman understand that we felt we needed this time for ourselves.

What happened from there was a lot of dialogue, and I think that changed some people. Some of our women were partnered with women who were not of color. We later learned that the Asian woman had a partner who was white. That was the first time we had a dialogue about why white women couldn’t come, and what was the purpose of that. At that point, it began to be questionable about who LWOC was.

None of the events we held were for women of color only. None of them. They were open to all women. But the organizational meetings and the mission continued to be focused on women of color. The Asian woman just did not agree that the organizational meetings should not allow women who were not of color.

At some point a little later, people got less interested in the political side, and LWOC started morphing out of what I knew it to be, which was a political and social organization founded to do educational socializing and community involvement, into more of a social group, which became the Gatekeepers. A [lesbian] couple, Lil and Bootsie, were part of the LWOC membership who didn’t seem to want to be involved in educational and political programming. They wanted it to be more of a social organization.

At the time of the split, and that’s how my memory is bringing it to me, there was dissension between that couple and the core LWOC group (myself, Lisa Boone-Wadji, Robin Troublefield, and others). At some point, people stopped referring to us as LWOC and started referring to us as Gatekeepers. I let go of all of my involvement, and I was no longer doing anything with Gatekeepers.

My memory of all that is foggy. I know that organization [Gatekeepers] grew out of LWOC, and that LWOC was my brain child, and my passion, and my identification. Of course, there are always many more women involved behind the scenes. Getting the ad in the paper, asking the question to my friends, beginning the group meetings at my home, I own all that. But the organization itself grew into the political, social, and educational piece that it was because of other women who had the same vision as I did. The two other women most closely involved in the beginning of LWOC were Robyn Troublefield and Lisa Boone-Wadji. Lisa had been married to an African man, had two boy babies, and had just come into her lesbianism.

Gatekeepers grew out of LWOC, and they pretty much ousted me from the head of LWOC. That was a very stressful time. I remember being with my partner (now of 23 years), and I cried like a baby that they ousted me. It was a horrible situation. Then LWOC was over, and Gatekeepers became the new name. They did lots of social events, and nothing activist or political that I can remember. I believe LWOC lasted three or four years before Gatekeepers took the helm, so that was 1991-1993 or 1994/95. In the work that I did after that, I identify it as the work of LWOC, but LWOC really did not exist by then as an organization.

After LWOC

TP: Some things came about later because of LWOC and my interest in programming for women that was more than social. For instance, I was involved in facilitating an African American, educational, counseling group. It was an eight-week group, starting in October 2001. [Reading from a document] “The purpose of this group is to provide a nurturing and therapeutic environment in which Lesbians of African descent will be empowered to enhance their emotional and spiritual growth. Friends Meeting House, $10/session.” Facilitators were myself – Terrie Pendleton – and Aqueelah As-Salaam.

I also facilitated an African American, lesbian, educational, counseling group, the Connection Group, held October 16 to December 4, 2002. It was for “Lesbian, bisexual, and questioning women connecting for support and personal growth. This is an 8-week, drop-in group.” We had a sliding scale, $7 to $10. It was a good group. That was something that came out of my desire to have a group where women could come and to talk about themselves, their lesbianism, their culture, and hopefully, to get a better sense of themselves.

TP: I don’t know if I can be considered ever as a member of Richmond Lesbian Feminists. I sent money to them, I got their newsletter, and I went to some of their events. Yes, I guess I could be considered a member. I knew them and I was involved with Richmond Lesbian Feminists before starting LWOC, but I never voted or anything like that. I was just a member at large, not a core member.

When I started LWOC, RLF was supportive. I worked with Beth Marschak quite a lot in getting Richmond Lesbian Feminists and LWOC to do things together. For a long time, they contributed material from their newsletter to our newsletter, Lesbian Women of Color: Information You Can Use Newsletter. Robyn Troublefield managed that newsletter, along with the core group. That started in 1992.

[Excerpt from a LWOC newsletter]: “Lesbian Women of Color encourages submissions of news events and information welcoming to the lesbian. If you wish to put information in our monthly calendar, please contact Lisa. Publicize your party meeting, etc., utilizing LWOC’s resources. Community info courtesy of Richmond Lesbian Feminists.”Many women of color did not get the Richmond Lesbian Feminist newsletter. They didn’t even know what it was.

You asked the question about how we managed finances. LWOC had no financial background. We were not as organized around finances as RLF was. I remember a beautiful Christmas event we had once downtown. We sold tickets, and the money just went back into a pot to help to do something else. Women donated money, and we used it to produce the newsletter and social events, renting a hall for events.

Lesbians of color, in my best understanding, being a lesbian of color and having been involved with many women of color who are lesbians, I don’t think we have seen the need to get involved. We stay in our community. We know we are lesbians. However, the whole political aspect of being gay in this Richmond community never seemed to faze women of color. It just wasn’t part of their world, meaning by that, what is going on with their family, their church, their job, their partner. They just weren’t interested in gay activism. I know African American lesbians who went to churches that denounced their sexuality; but they still went there because it was their church. It was their community.

I think they would involve themselves in activism around race, but I don’t think they did much with the women’s movement. I don’t think that was unusual. For people of color, race trumps everything. Who am I? What can you see of me? You first see that I’m Black and that I’m a woman. Unless I tell you I’m a lesbian, you don’t see that. So that’s not as important to fight against.

TP: I was involved in Equality Virginia, before it was called that, for a long time as a member, attending rallies and working on behind the scenes and stuff. I have also been involved with ROSMY, Richmond Organization for Sexual Minority Youths.

One of the things is that, even though now, in Richmond, you see more African American people involved in activism, there are still not many people that the [lesbian] community can call and ask to do something. I myself have moved away from the gay activism scene. When we’re looking for people of color to be involved in things even in 2016, there are very few in this area. I don’t know what that’s about.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University.

Terrie L. Pendleton, for more information, see also:

AIDS Changes Everything: Terrie Pendleton [sic]. Videos from the RVA, LGBTQ History Event, June 2, 2014 at Richmond Triangle Players, sponsored by SAGE.

Archives, Richmond Lesbian Feminists

http://www.gayrva.com/tag/richmond-lesbian-feminists

Marschak, Beth, and Alex Lorch, Lesbian and Gay Richmond, Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Prentiss, Apryl, “Celebrating 40 years, Richmond Lesbian Feminists were there for the best and worst of times,” gayRVA.com, July 18, 2015,

http://www.lgbtqnation.com/2015/07/celebrating-40-years-richmond-lesbian-feminists-were-there-for-the-best-and-worst-of-times/

Richmond Lesbian-Feminists, Facebook,

https://www.facebook.com/Richmond-Lesbian-Feminists-310820415707969/

accessed November 18, 2015

Shepherd, Suzanne A., “Dignity, Recognition, and Equality: Lesbian Feminists in Richmond, VA, 1974-79,” M.A. thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, History Department, Richmond, VA, December 2007, 88 p.

Terrie Pendleton at an LGBTQ History Program sponsored by Diversity Richmond at Triangle Players, July 2, 2014. “Activism: Terrie Pendleton” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F_jqc5eqLj0

[1] We have been unable to confirm the spelling of this surname.

[2] This duplicates the wording of one of the documents that Terrie Pendleton mailed to Rose Norman, but is not the exact wording read during the recorded interview, which reads slightly differently, as follows: Lesbian Women of Color is an organization founded to provide support for lesbian women of color, to share experiences related to racism and exclusion, explore multicultural connections through music, traditions, rituals, food, dance, and art, educating ourselves and others outside of the African American community regarding issues regarding lesbian women of color, and to create a network of lesbian women of color so that we may better understand and respect ourselves and others.