Blanche Jackson: Market Wimmin and Maat Dompim Womyn of Color Land Project

Edited for the web by Merril Mushroom, notes from phone interview by Rose Norman on March 26, 2013

Blanche Jackson: I had a 2500 square-foot loft in New York with two wood-burning stoves and a roof garden. People stayed with me from time to time. Someone told me about this nice woman who had just graduated from Hunter College needing a temporary place to stay in New York. She turned my roof garden into a roof farm. At some point, we asked ourselves why are we carrying horse manure up an aluminum ladder to an expanded platform, and then up another aluminum ladder to a trapdoor. Why don’t we live someplace where you can just put the seeds in the ground, and the ground is right under your feet?

About that time, the early 1980s, I went to a Quaker lesbian conference in a place called Heathcote in Maryland. They said they were looking for more members. I went back and told my then-partner, Amoja Three Rivers, about it. We decided to move there. That’s how I got out of New York.

A few friends loaded up a rented truck, and a couple of them followed us to Maryland to see what we had gotten ourselves into. The kindness of our friends to this day touches me deeply. That place turned into kind of a snake pit for us. After four months, presentation mode fell away. We got into the nitty-gritty of what this group was like. I had a little bit of savings, and I bought an Isuzu truck. When we announced we were leaving, trying to be considerate, that just enraged the person who was the head honcho there. The next thing we knew, we were being taken to court. Now, I had paid my rent up until the last two months, and partial rent the last two months (there was a problem with my loft in New York). The rent at Heathcote was twice everybody else’s rent because I wanted a cabin on the hill. It had a kitchen, but no bathroom.

Biographical note

Blanche Jackson, born in Brooklyn Hospital, Brooklyn, New York, grew up in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, the youngest of three children. Her parents were in their late 40s when she was born. Her sister was sixteen years older, her brother twelve years older. She attended Catholic school the first five years of school; then, she attended public schools, all in Brooklyn. Four years after graduating from high school, she started a two-year program in advertising and public relations at a community college in Manhattan. She was one of only two students who completed that degree in the night school program. She worked in advertising long enough to know she wanted to do something else.

They kept sending us summons, and I answered the first summons. A friend had loaned me a lawyer who told me it was a frivolous suit that a judge would throw out, and they’d leave us both alone. I answered my summons to show the community it was a frivolous suit.

Did I mention there was also a snowstorm? It was the worst blizzard in 20 years—and the cabin was on a hill? I would try to get my four-wheel-drive truck up the hill, and it would slide back down. I did not get out of the cabin when I intended to get out, and we were marooned in Baltimore for a while. And the court process didn’t turn out the way we expected. It was a strange thing. One person from the community showed up at court with her friend. They swore us in, including swearing in the friend without ever asking her name. I found this alarming. The judge decided that I owed them $3000 although I never followed the logic of why. The judge did tell them that the document they were using as evidence (a lease on notebook paper with no year on it, with the heading “Heathcote Community”) had no legal standing because of the “Heathcote Community” name on it. Then they said, “Heathcote Incorporated,” and the judge allowed the case to proceed. (Earlier, I had actually bought some lease forms at a stationery store and tried to get them to use them, but they kept ignoring this at meetings, and I had given up. When they finally got around to doing my lease, I didn’t have those forms with me. That’s why the lease was handwritten on notebook paper.) The judge decreed that I owed $3000. But he told them that since they were a corporation, they would have to use their corporate lawyer proceed with the case.

BJ: While we were at Heathcote, we met a wonderful woman, Vickey, whose parents owned a plant nursery in Pennsylvania. Vickey would come from Pennsylvania to show us how to make the chicken coop that Amoja had made livable [for us], insulated and everything. Nobody from the community would help, but she would come from Pennsylvania to do it. Her parents gave us a little plot of land, and we grew gourds. Before we left New York, we had taken percussion lessons. We were going to women’s music festivals, and Amoja had timed [the crop] so that we could leave, and the day we came back the gourds and vegetables would be ready. She planned things out. She could do things like that.

England Women’s Music Retreat (NEWMR), and lo and behold, Heathcote had a booth right smack in the middle of the space. So, we set up, put out our six shakerees, and sold them all. We took the money, bought some food, bought some gas for the truck, and spent the rest of the money on fishline and beads, materials to make some more shakerees to sell. This is the business that became Market Wimmin, which also sold Amoja’s book, Cultural Etiquette: A Guide for the Well-Intended (1990).

We went to festivals from the Delaware Water Gap to New England, and from Mississippi to Wisconsin. We traveled half the country more than two hundred days a year. We were renting a little, 175-year-old cabin in Floyd County, Virginia, from two women. We would spend the winter there making shakerees and other stuff. We would spend the entire spring and summer going to women’s music festivals and the People’s Music Network, which had two events a year. We went to both for about four years. At one of them, Faith Nolan from Canada (who we’d met at women’s music festivals) walked in with Pete Seeger. In the fall, we would sell our crafts at college campuses.

We did that until one year, while we were travelling, the cabin burned to the ground. We bought plastic beads; and we had all of these bags of beads, every bag holding 20,000 beads, the bags stored in the rafters of the cabin. All gone. Our winter clothes were gone. It was really devastating.

Someone from the Red Cross came from Roanoke take a list of things we had lost. He didn’t think he could replace books. Amoja had her research books stored in metal milk crates. You could actually read the titles of the books in the crates; but when you would touch a book, and it would turn to ash. The Red Cross gave us vouchers for winter clothes and shoes. (They didn’t replace food.) Eventually, we convinced them that Amoja’s livelihood depended on the books that she had lost. She was doing workshops on African herstory and that kind of thing; and we got vouchers for books. A bookseller friend of ours (Leslie Smith) would track down the books she used, though some were irreplaceable. So, we put the business, Market Wimmin, back together as best we could, renting a house in West Virginia for a couple of years.

BJ: Just before the fire, we had been doing workshops at women’s festivals about women’s land and about what women would want in a land site. The way I thought about it was not so much that it was women of color land, as that it was land that reflected the cultures and values of women of color. Personally, I didn’t care who came. I wanted the culture and the atmosphere to be reflective of many cultures. I didn’t mean Black. I meant African American, Native American, Latina, Asian. I wanted to do something that offered something to all of those groups.

“Maat” is the name of the ancient African Goddess who represents balance, truth, and justice. “Dompim” means “a place in the bush where the voice of the Goddess is heard.”

Maize 45, Summer 1995, p 7

Women had been giving their input in these workshops and seminars. When the cabin burned down, oh, my god, women sent us clothes and money. We went right from disaster relief into fundraising for this land. Our first fundraising letter went out under a heading that said, “Phoenix Rising from the Ashes.” The first name we had for the project was Shakti Root. I asked a Southeast Asian woman what she thought about that title. She said that she didn’t mind it as a working title, but she didn’t want to drive in through a gate that said Shakti Root if the people doing it were not Indian. So, we changed the name to Maat Dompim. [“Maat” is the name of the ancient African Goddess who represents balance, truth, and justice. “Dompim” means “a place in the bush where the voice of the Goddess is heard.” Maize 45, Summer 1995, p 7.]

On the trip before the cabin burned down, some women in Missouri had given us a computer. Before we went on the road, we carefully stored it behind the couch, and of course, it burned up. Then Sarah Hoagland and Anne Latham gave us a computer. We knew them from Michigan [the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival], where we hung out with them. We would visit at their house in Chicago after the festival. This one year, we were going to skip Chicago, and Sarah kept saying we had to go to Chicago. Finally, Sarah said that we had to come to Chicago to get this computer they had for us. I got some intensive computer training from them there. They pumped as much computer information into my brain as they possibly could before we left Chicago.

That computer was crucial to the process of promoting Maat Dompim. We did constant newsletters. We kept in touch with every woman we met who merely rolled over in her sleep and said “land.” If we had any way to get in touch with her, we did. The biggest chunk of the first money we raised went for mailings. And women did donate. It was amazing. When we finally did buy the land in Virginia, we could have paid cash. We didn’t because we had a clause in the deed saying that if we found anything wrong within some time period, we could get our money back. So, we gave them a check.

BJ: When we bought the land in Buckingham, Virginia, we were living in Auto, West Virginia, renting from a gay guy who had built the house himself. I loved that house. When I walked into that house, I thought I had built it. It was such a good fit. Then, we moved to Buckingham County, Virginia, to be close to the land that we had bought. There was this beautiful old house with tongue and groove paneling, ornately carved banisters on the staircase, beautiful hardwood floors. Come to find out, a Black woman had inherited this house, and then she built what became known as the Hilltop Hideaway, a “juke joint.” A family who lived about a quarter of a mile away said that when the juke joint got going, their floors would vibrate.

We rented the converted “juke joint” to live in. It had a barbecue pit outside, and it had a fan built into the ceiling, the most powerful fan that I have ever encountered. If you wanted to use the wood stove, you had to open the windows. Otherwise, that fan would suck the smoke right into the room. You can just imagine people in the 1970s, partying their hearts out, and everybody comfortable because of this fan. What the new owner did to make this rentable as a residence was to turn what had been the men’s room into a shower, taking out the toilet and sink, and putting a drain in the middle of the floor. The ladies’ room became our bathroom. Off one side of the building was a narrow room that we divided into two bedrooms. They told us that this long, skinny room had been the pool parlor.

The woman who inherited this whole place, not only did she build the juke joint, but a brick house, too. And in between them, a swimming pool. And then she sold the whole kit and caboodle to the family who had once owned her family. I always wanted to meet this woman. If only we could have been renting from her.

People were renting the brick house she built. The original house she inherited was full of the new owner’s junk, so, we rented the juke joint. It was about 30 feet from a cell phone tower. I asked a friend what it does to you to live by a cell phone tower. He said we were in the donut hole, out of the way of all the transmission waves, which were aimed toward the highway. We had a great garden. It was good.

BJ: We did the 2000 census; and we did it so long that we qualified for unemployment when it ended. Buckingham is not a rich county. Some were opposed to the census, but they were nice to us. Then we got up to the more affluent area, such as Afton, and they would say, “What are you people doing here? You’re wasting your time and my tax money.”

We went to some scary places. We went to one place three times and never got out of the car, there were so many dogs, and one time there was gunfire. We would just hang a notice on the branch of a tree, and come back and tell our supervisor we wouldn’t go back there. One time, at another place, a guy emerged from the shadows with both hands behind his back, kind of unfriendly. We thought he had a gun. Our supervisor went to check that out, and he found out from the neighbors that was just the way the man stands, hands behind his back.

BJ: We had some money for a change, and I got my teeth fixed. And Amoja and I both got physical exams. After her exam, Amoja came out looking like she did the day the cabin burned down. The x-ray had turned up a mass that needed to be tended to. Next thing we knew, she was on the fast track to surgery. I went with her to all the meetings with the surgeon, and I later found my notes. In my opinion, they overdid it. They went in there and took more than was necessary. They grabbed every organ that could be grabbed, just in case it might be malignant. And it was not malignant. It was just a big benign tumor.

When we lived in Maryland, one of the things we did was pelvic training for medical students. Amoja had done that, and the supervising doctor told her she had a pea-sized cyst. Amoja told the doctor that a woman who did reflexology already told her that. She had a back and forth with the doctor, who said reflexology couldn’t determine that. Apparently, in the intervening time, that little-bitty cyst had become the size of a grapefruit. Before Amoja’s surgery, they said it would take four months to recover. After the surgery, they said it would take twelve months to recover — twelve months with no income. The longer recovery time was because since Amoja had no health insurance, the doctors did more in the surgery than they would otherwise have done, requiring a longer recovery time.

I got a job three miles from where we were living, running a thrift shop in a community center. It was meager money, but it was something, and the job was close. It meant that I wasn’t gone that long. I would be around to help Amoja cope.

She was supposed to be back Monday. Monday came and went.

In November of that year, the wife of the family we were renting from raised the rent. Somehow, we paid it. Then, on December 15, her younger son and his wife left a note on the door saying that we had 30 days to get out because they wanted the place. We started packing, and Amoja wasn’t supposed to lift anything heavy. We had built things out of cinder blocks and old doors, and other things, and it was pretty nice. I had my dream office. We had written a grant to get a photocopy machine, we had a computer, and we were all set up. Now, we had to take it all apart. On approximately December 20, I came back from work to find a note from Amoja on the kitchen table. She wrote that her mother was sick in Minnesota, and her sister (who worked for an airline) had gotten her a plane ticket to Minnesota. She was supposed to be back Monday. Monday came and went. Her sister had given me her mother’s number, and Amoja had given me a number, and they were not the same number. I called each number, and both of them were wrong. I tried out a number in between the numbers they had given me, dialed that number, and Amoja answered the phone. She told me to check my email. She had sent me an email saying she was going to be staying in Minnesota. She didn’t say for how long.

BJ: By this time, I wasn’t working at the thrift shop anymore, but had gone to work at a Habitat for Humanity office in another county. We didn’t have the Isuzu any more. In 1992, the book was selling, and the shakerees were selling, so we bought a Ford F150 truck. After we left the juke joint place, I had rented an old trailer I called the “Cracked Can.” I was living there, and keeping stuff from the juke joint in a storage unit. I had a friend, Connie, that I’d met while taking classes for the census, who was coming to our juke joint place to help me. She would pack and seal all the boxes, without labeling them, and I’d load them into the truck to take to the trailer or to the storage unit.

Around that time, I noticed I was standing crooked, falling down sideways. I weighed myself, and discovered I had lost 28 pounds. Fortunately, there was a couple with a place near the juke joint. He had a car repair and she had a convenience store, where I started having breakfast. One time, the truck died up on the hill, and he fixed it. That was very lucky since this was a very thin [sparsely populated] area. But at least I had a place to get an egg biscuit and get my truck fixed.

I got the juke joint emptied out with help from my friend Connie, and I moved into the Cracked Can. Later, I found I had crossed a county line when I moved 1.8 miles down the road. Now, I was in Appomattox County, driving this big Ford F150 all over the place, looking for a job. It was 40 miles to the unemployment office. The system then was that when they found a match for your skills, they would send you a letter, and you had to bring that letter to the office.

How you get a job in Appomattox is somebody who was born and raised in Appomattox has to really like you.

Well, after driving all that way and waiting hours to see somebody, they’d tell me the job they’d told me to come for was for an accountant – not my skill. The next time I got a letter from them, I got them to actually read me the job description over the phone before making the trip.

I did not get a job that way. An organization called Green Thumb had gotten me the jobs at the thrift store and Habitat for Humanity. Green Thumb is an organization that paid people to work at nonprofit and government facilities. I also worked at Surrender Ground (the national historic park where Lee surrendered to Grant at the end of the Civil War). I worked at a library. They paid for 20 hours a week, $5.50/hr. I struggled along with that until I was assigned to the Chamber of Commerce office in Appomattox. I hit it off with a young woman who was the secretary of the Chamber. She also drove a school bus and got me a job working as an aid on a school bus. How you get a job in Appomattox is somebody who was born and raised in Appomattox has to really like you.

BJ: By 1990, we were going to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MWMF) and the North East Women’s Music Retreat (NEWMR) every year. Amoja had been going to these, and after she moved into my loft in Brooklyn, I started going with her. The Michigan Festival was in August, and NEWMR was in September. Women of color who worked at both of those festivals would have a meeting under a tree at NEWMR every year to talk about their experiences.

The first year I went, the topic came up that, you know, you see a sister on the path, and then you never see her again because there are 3000 women there. First, we thought of having a women of color campground, but that seemed too much like segregated housing. Somebody said, “What about a resource tent for women of color who want to connect or who want to share cultural stuff?”

We’d have reading materials and all that, and everybody agreed that’s what we wanted, a resource tent. We went home. I decided to organize transportation. Instead of renting a bus, which is expensive and hard to fill, I decided to reserve a van at all the car rental places for a certain date. I know they overbook at these places, so I would overbook myself. Every time we’d fill a van with five people, I’d book another van. So that was my system. I organized the vans and got women lined up to drive the vans. I had a whole game plan about which vans are going where, and who to pick up. They’re all going to meet someplace and caravan. That way if anybody has problems on the road, it’s not just five people in a van having a problem.

Those tents are where the discussions took place about what women of color want,

about if there was land for women of color, what they would want.

Amoja and some other women had contacted both festivals about this idea for a resource tent. NEWMR said yes right away. Michigan [MWMF] (not sure just who, think it was Boo Price) responded, and said she thought it would be divisive, that we should all be sisters together, melded and everything. Amoja and others went and negotiated really hard at Michigan [MWMF], and they succeeded in getting half of a tent, I think the political tent. It overflowed. Women flocked to it. Michigan [MWMF] the next year gave us a small tent, and it overflowed so much that the tents grew bigger. Those tents are where the discussions took place about what women of color want, about if there was land for women of color, what they would want.

BJ: The workshops and seminars we did always assumed there would be land. We started with that, and we focused on the vision for that land. Now, I felt like, heck, if we’re going to have this land for women of color, we don’t want it to be twenty women sitting around negotiating who’s going to do the laundry or cook dinner that night. I wanted a place where individual women, where as many women as possible, could use it. We needed a system, a structure, and a strategy that would accommodate a flow of women rather than a static community. This was hard to convey. People kept asking me about the community I was trying to start. I kept trying to tell them, “I’m not trying to start a community. I’m trying to develop a facility.”

Another thing we wanted was some place that was not busy, busy, busy. The festivals were a great place to meet people, but they weren’t a great place to explore relationships or to develop anything permanent. Everybody’s running to workshops, and to this place and that place. We wanted a place for communication and contemplation.

People told us it would take us five years after we got incorporated to get nonprofit status, but we got it in a year and a half. We’d been raising money since the fire [when the cabin burned down], and we were shopping for land. We would do the festivals and the college campuses. What little time we had in between, we’d find some cheap place to stay to explore that area [looking for land]. We would go anywhere. We were in Tennessee, in Maryland. We were even going to fly to Minnesota one time because some women told us about land next to them that was for sale; but the land sold before we got there. And I think that was good. I’m into a long growing season.

People would say, “When you get the nonprofit status, we will come.” … “When you get the land, we will come.” … And they did come, and they ooh-ed and ahh-ed, and then, they went home.

A lot of discussion took place about what women would want in the tents for women of color tents. We had boards where women wrote it out. We put posters up. Women were enthusiastic. They’d say, “If you get a place, I’m in!” A woman who had written about her experience on some women of color land in another state, maybe it was Arco Iris in Arkansas, which is still going, or La Luz de la Lucha in California, which is no longer together. She said, “If it’s in Virginia, it would be more convenient for me. But wherever you do it, I‘m there!”

People would say, “When you get the nonprofit status, we will come.” (We did that in 1992.) Then, they said, “When you get the land, we will come.” (We did that in 1998.) And they did come, and they ooh-ed and ahh-ed, and then, they went home. Then, Amoja had surgery, and here I am a ghetto brat from Brooklyn in the “heart of the Confederacy,” sloshing around trying to survive. And the land is sitting up there paid for.

BJ: No. We had supported ourselves selling books and shakerees. We raised money for the land through donations to the nonprofit, Maat Dompim. Of course, most of the women who gave us money didn’t really get a tax break, because you have to be in a pretty high tax bracket to get a tax break. We didn’t care how little people donated. If somebody sent us a dollar, we sent them a thank-you letter saying they had donated to Maat Dompim. We also got a grant from LNR [Lesbian Natural Resources], the organization that Lee [Lanning] and Tamarack ran.[1]

A Native American woman came to where we were living in West Virginia, and she helped during the incorporation part, doing some of the typing on the computer and other paperwork. That woman was strong. One time, I saw her lift a whole bale of hay!

We got help from her, and from some women who came while we were living in the “juke joint.” There was not a consistent group of women who did specific things on a consistent basis. There were things that needed to be done physically to the land, there was more paperwork, and there was research for grants, such as for “open recreational space.” We couldn’t do it all. We were making shakerees and selling stuff just to feed ourselves.

My original slogan was “Design Your Own Involvement,” but it seemed people would design my involvement. I had already done everything I said I’d do. I’d incorporated and gotten the nonprofit status, I’d found the land, which I agreed to do, and I did all kinds of stuff that I did not agree to do. It just got harder and harder. And then, Amoja had surgery, went to Minnesota, and she was out of the picture. I’m not that talented. I could barely keep myself fed. I was living in the “Cracked Can,” sleeping in a chair because the ceiling in the bedroom had turned blue from mold, and I was afraid to sleep in that room. It was horrible, really, really horrible. It was so cold in that place, I was sure I’d be dead by spring, frozen solid in that chair. I would tell myself to be glad that I didn’t have anything to bequeath, and I didn’t need to go to the trouble of making out a will.

BJ: No. The juke joint we had rented (and got forced out of) was couple of miles from the land. You could hike from the juke joint to the land. The Cracked Can was another 1.8 miles from the juke joint. All that threw me into ongoing permanent survival mode. Ever since then, I’ve been trying to resolve what to do with the land. I tried to give it away. One of the problems is that the access road needs work. The land itself is beautiful. It has some of the most beautiful views. It’s 109 acres, and there are another 24 acres under a quit claim deed.

BJ: Not-for-profit still exists, but the nonprofit designation had lapsed. I would have to do paperwork to re-establish it. It’s do-able, but it lapsed. I can keep the state thing up – it’s $25 a year. I just pay that out of my own pocket. The taxes on the land ate up the Maat Dompim bank account. I stopped paying the taxes thinking it was better to have a little seed money in case there was something that could be launched, rather than to pay the taxes, deplete the fund, and not be able to pay the taxes anyway. So, it’s sitting up there piling up taxes in Buckingham County. I’m in Appomattox County, where there is no women’s community.

We did have the money in a bank on the Beltway [in Washington, D.C.]. We don’t have anybody on the Beltway anymore, so I recently transferred the money to a bank closer to here. Every once in a while, somebody turns up, and they are interested. And then, it falls through. There was a group that came regularly for several years saying that they would do this that and the other. They would go back to their several homes around the country, and that would be the end of it. I’m a team player. If you say you’ll do something, I say what part I’ll do, and then we do it. I’m not very good at massaging and cajoling and inspiring. If we want to do something, I’d rather just get on the stick and do it. When people say they’re going to do something, and don’t do it, I’m done.

A friend of mine in Canada has been a big help. It was so good to have somebody to consistently work with. We tried to find out whether we could sell it if the funds would go to a more manageable place. But that was tricky. How do you sell a non-profit asset?

One thing you can do is get a conservation easement on it. That lowers the value of the land, and thus the taxes. Though it is a lot of trouble to do that. I know, I’ve got the form.

How much are the total back taxes owed? They’re not very high in this area. Maybe $2000? It’s under $5000. I’ve tried to find other groups who would take it over. The thing about it is, if some group had the resources to hold onto it, that 109 acres is the only stand of hardwood on that mountain. It even has a spring. Eventually, the road thing is going to be resolved.

You know, it’s funny. There were all these positive omens and signs, and suddenly everything came together. And then. everything fell apart. This is a land story that I’ve heard before in different versions: everything comes together, and then, everything falls apart.

I thought if we got a place, women would just take ownership of it collectively.

Michigan [MWMF] is going into what, it’s thirtieth year or something? [In 2016, it was 40 years.] When we had the women of color tent there, there were these women who would come to that tent and ask, “What’s this about?” And we’d say, “It’s your tent!” And they’d say “Huh?” And we’d say, “There’s the poster board, there’s the magic markers, you know, all the materials. If you want to do a workshop, or if you want somebody else to do a workshop on a topic you’re interested in, post it.” Faith Nolan did her first performance at Michigan at the women of color tent.

I thought if we got a place, women would just take ownership of it collectively. One person suggested that the problem was that people as individuals wanted to own. They want to own, own, own. But I know places where women bought two-acre lots individually, and they fell apart, too.

I thought the women of color land would be like a great, big, women of color tent. We tried to write the core proposal for the land project like a honeycomb, so that it had a firm structure, but with a lot of open spaces where women could plug anything in. Like, there was all this controversy about women with sons. Well, we could have a women with sons conference every year. Other women would say, “Oh, no, then there would be boys walking on the land.” And I’d tell them, “There are hunters walking on the land now because nobody’s there.”

Shewolf tells a story of her land in Louisiana, Woman World. She thought that if you had the land and invited women to live there, they’d come. She was even willing to give away pieces. They’d come for awhile, and then leave. She did run workshops there for a long time, teaching skills for living on the land, but nobody settled there permanently. “If you build it, they will come” just didn’t work out for this case.

I knew the women on that land in Ponca, Arkansas [Arco Iris, see www.earthcareproject.wordpress.com]. For me, I did not want to live in Ponca, Arkansas and I didn’t really want to live in Minnesota, to tell you the truth.

BJ: I assume. I have not heard from Amoja in a very long time. Pretty much, as I said, she left a note on the table. I called some phone numbers. She told me to check my email. I would write her notes, and for awhile she would write back. But she never answered any questions. If I asked a question in an email, she didn’t answer it, even if she wrote back. I heard on the grapevine that her mother had died. About a year later I got a little note from Amoja saying that her mother had died, and that she’d gone to Arkansas where her family had come from. I think they buried Amoja’s mother in Arkansas, not that Amoja moved there. As far as I know, she was living in an apartment complex in Minnesota.

I’ve been really out of the loop, just treading water. Somebody sent me a copy of Lesbian Connection. That’s the first one I’ve seen in a decade! I’ve just been applying for jobs and counting pennies.

Everything that I did in my life was satisfying, but it was brutally hard.

Right now, I’m in a situation where I live with a 92-year-old woman. I’ve been living with her for seven years. She didn’t want to live on her 119 acres by herself. For me to live on 119 acres, and to have three dogs and a cat, I can put up with her! My relationship with the woman has mellowed over the years. We’re now in a place of mutual accommodation. (Her daughter, who lives six miles away, is another thing altogether.) It’s as close to how I want to live as I’ve been able to get: walking out the front door and not seeing another house, being able to have animals. But I’m an adult, and I’m living in the two rooms that her daughter lived in as an adolescent and teenager. It’s not really adult accommodation. It’s also hard sharing a kitchen with someone who has an entirely different kitchen habits. So, it’s not perfect. We have our difficulties. One of the good things is that I’ve been able to keep still for awhile… and think… and work the kinks out of my neck.

Everything that I did in my life was satisfying, but it was brutally hard. Market Wimmin, you know, the business, was brutal. When we started out, everything was in cardboard boxes. If I got to an event and it was raining, I could not put down the cardboard box until I got to someplace safe and dry to put down the cardboard box. You sell at college campuses, and sometimes, they want you to park on the other side of the quad, and then, go upstairs on a two-person elevator. Shakerees are made from big gourds, and they don’t fold. We had shakerees, we had t-shirts, we had neck wallets, and we had the book, Cultural Etiquette: A Guide for the Well-Intended. We also had other crafts women’s stuff, women who didn’t want to travel. We would take their stuff, like rain sticks, Snake & Snake t-shirts (in addition to our own t-shirts).

Susan Baylies of Snake & Snake [www.snakeandsnake.com] is a genius, a silk-screening genius! One time I asked her how she consistently printed with metallic ink. She said, “Because I was alone in a little cabin with a little boy, and I didn’t know any better.” She did some of our most brilliant t-shirts. She did so well, had so much volume, that she actually began to refer us to some other women who were silk-screening t-shirts, and it didn’t come close. She folded everything, too. When you got it from her, it was ready to put on the table. She also does lunar charts and feminist jewelry.

* Amoja Three Rivers, 1946-2015. See obituary at: https://www.smashwords.com/profile/view/amoja3rivers

[1] Maize: A Lesbian Country Magazine regularly reported grants issues by Lesbian Natural Resources (LNR). Awards were made only in the year the land contract was issued; otherwise, people had to request the money again. From 1992 to 2000, Maize reported, “Land Development Grants have funded $139,900 in down payment grants, $31,400 in mortgages, $61,810 in housing, and $59,278 in development” (Maize 62, 1999, p 31). Maize reported a $15,000 land purchase grant to Maat Dompim in 1994, which was renewed in 1995, 1996, and 1998. In 2000, Maize reported a grant of $8000 for “a building for two residents” (Maize 67, p 30).

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

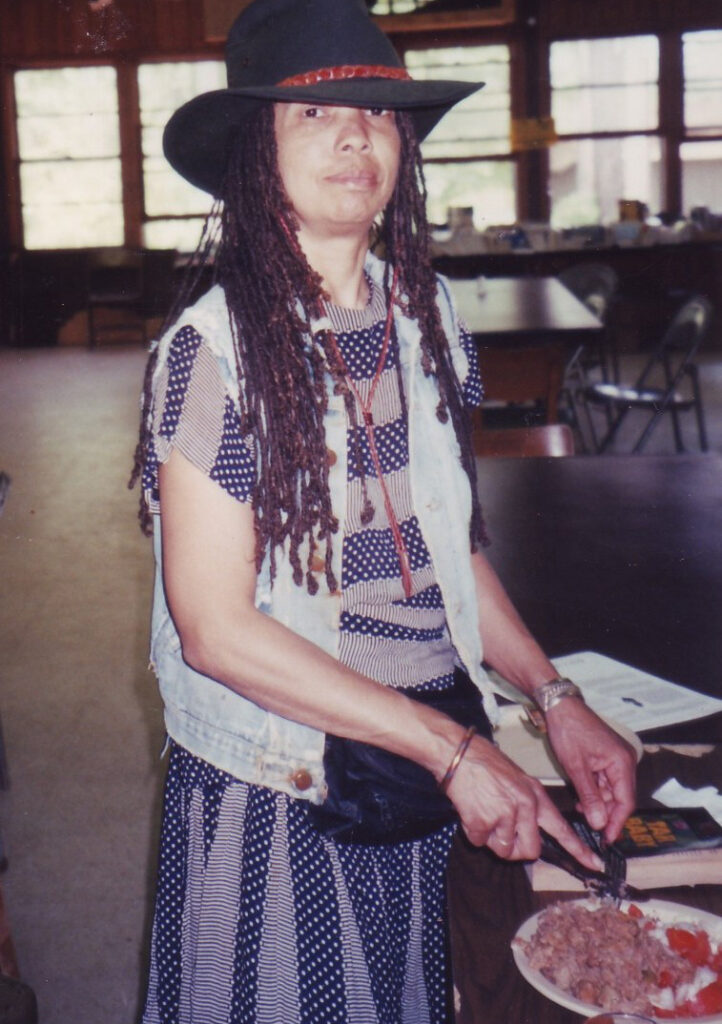

“ ‘A Great Big Women of Color Tent’: Blanche Jackson and Maat Dompim,” Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 150-56, written by Merril Mushroom using this interview and a memoir that Blanche Jackson wrote after doing the interview. Merril Mushroom also contacted Amoja Three Rivers by phone, and sent her a copy of the article (not this interview) for comment before publication. She got Amoja’s permission to include a photo of her taken at Womonwrites in the 1990s, which is also included in these interview notes.