Ellen Spangler and Starcrest

Interview by Rose Norman at Alapine Village on September 29, 2019, and February 29, 2020

September 29, 2019, Alapine Village, Alabama

Ellen’s Background in Feminist Spirituality

[edited narrative]

I have been involved in various kinds of feminist spirituality groups since I attended the first women’s spirituality conference, in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1976. [The conference program is online at https://jwa.org/sites/default/files/jwa032c.pdf.] Some of the leading women in women’s spirituality were there, including: Z Budapest, Mary Daly, Ruth Mountaingrove, and Kay Gardner. I first began doing new Moon circles when I lived in Jacksonville, Florida. The biggest circle, though, was one that we formed in South Carolina in 1984, where I had started a healing and teaching center called Starcrest.

When I moved to South Carolina, I found a large group of women, both straight women and lesbians, interested in women’s spirituality. Two of these women were Methodist ministers, who quietly and unbeknownst to their church, joined the planning committee for the women’s spirituality circles we had eight times a year at the equinoxes and solstices; and at the cross-quarter days, which are Candlemas, Beltane, Lammas, and Hallowmas. There was a little Baptist college in Anderson, South Carolina; and a woman snuck from there to come every time. Women came from many different religious backgrounds. We were particularly interested in Native American teachings. Our circles regularly had up to fifty people.

In the late 1980s, while visiting my sister in Arizona, I heard about a women-only Sundance out in the desert. I was already involved in the women’s movement, I had been doing hands-on healing work, and I was interested in Native American spirituality. As it turned out, I was able to do some healing work at the Sundance; and through that, I made a good, personal connection with Beverly Little Thunder. We later became friends, and spent time together. She came to South Carolina and helped us set up a women’s sweat lodge. The more I learned, the more all of it kept making sense. This was such a balanced understanding of creation and the world.

Interview transcript begins here. The first interview takes place in Ellen Spangler’s earth-sheltered home at Alapine, Alabama.

Ellen Spangler: Starcrest was the name of the healing-teaching center that I created. We had the circles there, on the five acres of land where I lived. The people I got to know through the healing center were also interested in women’s spirituality. The concept was so similar. The two Methodist ministers were on the planning circle where we planned what we were going to do for the equinoxes and the solstices, not just coming to the circles.

ES: Well, we said that anybody could come who wanted to plan. If there are any special things you want at this equinox that’s coming up, then come to the meeting or let somebody know. Even then, it was informal. Anybody could come to a circle and say, I want to make sure we do __, and that will be part of it.

The planning would go over what’s going on around the world this time of year, to educate all of us or remind us. They’d share things they had heard to be effective, so those ideas got the basic format for the circle. Anyone who came to the planning circle could add something. Maybe they learned a good chant and would teach it, and it would become a part of the circle. It was wonderful to have that planning group. I was the one who got it going, but I didn’t want to be a minister. That wasn’t the goal for me. Women’s spirituality comes from the group. They made sure things got taken care of, the nitty gritty, if we would need a fire, and so on.

Biographical notes

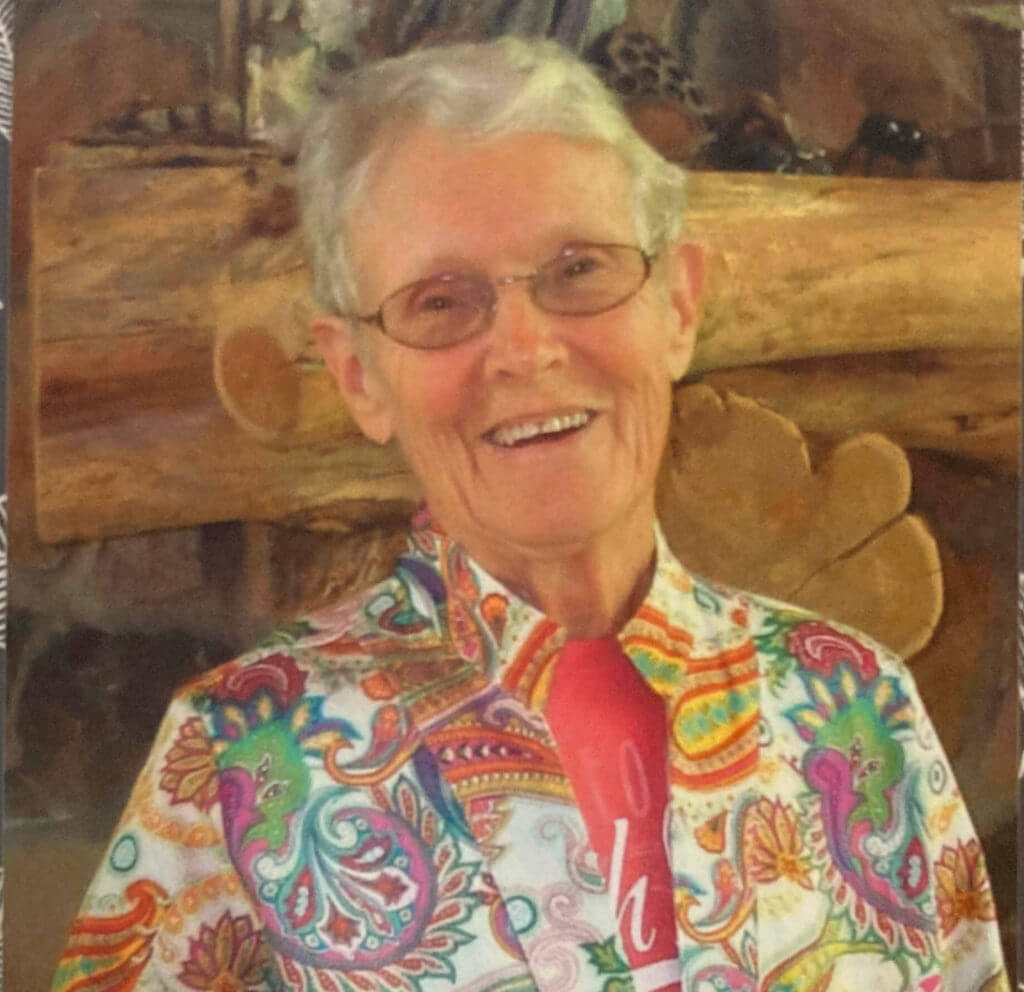

Ellen Spangler, born 1934 and died 2021, grew up in Illinois, where she started college. She became a feminist activist in 1970. She helped start a battered women’s shelter, the thirteenth in the nation, and a rape crisis center, both while attending college in Jacksonville, and while caring for her children. When Ellen came out publicly as a lesbian, she changed her last name to Spangler, to protect her children.

She was active in the Pagoda cultural center in St. Augustine, Florida, when she lived in nearby Jacksonville, during the 1970s and 1980s.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Ellen Spangler lived in South Carolina, where she operated a healing center called Starcrest.

(Read full bio.)

Mary Alice Stout, born 1945, grew up in Georgia; Mississippi; Washington, D.C.; and Tennessee, as her father changed jobs. She graduated high school in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and she went to the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, earning a bachelor’s degree in science education and a master’s degree in botany.

Mary Alice taught high school biology in Clinton, Tennessee, for ten years. When she met Ellen Spangler through a mutual friend in Knoxville, she was the executive director of the Knox County Education Association, a job that required lobbying for Knox County teachers and negotiating contracts. She left that job, moving to South Carolina to be with Ellen Spangler in December 1989, at age 44.

(Read full bio.)

We usually did cronings at Hallowmas, because we were honoring the wisdom we get with age. So many of us lived when young women were treated with respect, but old women were not. With Native Americans, it was just the opposite. Elder women are considered the wisest, the most knowledgeable, the most spiritual. Different ones of us learned about that. Croning was important because it helped everyone who came to change the focus about ourselves. Forget what that world out there says about women. It’s not true.

ES: No. I wanted to get out of Florida. It was getting too hot. At that time, I was living on a goat farm and trying to live holistically. I had friends who had moved to the country in South Carolina. When I visited them, they told me a 5-8 acre property right next to them was for sale. That made sense to me.

When I got up there, I didn’t know what I was going to do other than develop the land. I had bought an old house and moved it onto the land, and rewired and plumbed and repaired it, to have a home. I had been traveling and spending time with some Native American women, and I was sharing some of what I had learned with the South Carolina friends. About hands on healing, healing our hearts in a sense, and a different way of looking at spirituality. They suggested I teach a class about it. I had not done that before, and didn’t know how to go about it. How would I let anybody know? They told me about an alternative bookstore in Anderson, South Carolina, nearby, where I could put up a flyer.

How I teach is to gather people who know anything about the topic, and share what they know, so we all learn from each other. The first class filled up. I ended up with an 8-week class that met once a week. There were about a dozen people, initially all women, though the classes were not limited to women. At the end, they said they were ready for the next step, but I didn’t even know what to call the first step. We were doing an assortment of things—hands on healing, meditation, clearing chakras. The focus was on healing everything, mind and spirit; and it evolved in the group. They said, “Call it Psychic 101, and you’ll fill up!” So they wanted Psychic 102. I did it, and learned as I went along. I had resources and books I had studied or used. It was really a group development. After that first class, I built on a big room to use as a classroom. Very soon, men came to the classes, too, husbands and wives.

I became good friends with a Native American shaman, a Cherokee man who worked in the police department. He kept his shamanism hidden. He taught me a lot of things. Once a year we would do a men’s weekend workshop, where they would come with bedrolls and such. He was different from other men. I was a little older than he was, but he wasn’t a kid. The kind of respect toward women that was there, subtly, all the time, was different from other men. I felt that. And I shared that with him later on. One day he said he wanted to tell me a story that he didn’t usually tell people. With Cherokees, the shaman picks a grandchild when they’re born to be the next shaman in the tribe. So his grandfather picked him. But his grandfather was the first male whose grandmother had said, “It is no longer safe for women to do this. They are killing us.” And they were. The Europeans wiped out matriarchies when they came over. The women were considered the wisest of the tribe and the most caring, so they were obviously the shamans of that tribe. That helped explain the respect I felt from him that was so different. And he shared with me a lot of Native teachings that were really helpful and fit right in with the things that women were creating with spirituality. He emphasized what I had read from other indigenous people that what we refer to as God, that power, is much more than a person of any kind, but it’s there for animals and plants. We all work together. It’s not controlling anything.

ES: I created that name when I was moving up, buying the property, and still living in Florida on the goat farm with Rose DeBernardo. We were separating. It was a really unusual Moon. One of the planet stars was going to be hanging below it for a long time. We had gone outside to look at it, and it was really outstanding, a bright star just below the Moon. It was like that was sending me off, just shortly before I was moving. It was a different thing in my life. That just said to me that this property was going to be named Starcrest. That fit for the healing center, as it developed. One of the students who came to classes, after taking some classes, was doing stained glass, and she made a piece called Starcrest. [We move into another room to look at the stained glass.]

ES: Outdoors. My Cherokee friend told us how to really build a circle. You do a large stone at each of the directions. I think it’s three stones in between, certain things that were connected with the stars and the planet. There were a lot of loose stones around in the area. We found a place in the woods without big trees, big enough to do the circle, and a group of us laid it out. When the shaman came to look at it, he was in awe. He asked, “How did you know that the quartz crystal is supposed to go in the south?” We had picked the kind of stone intuitively for each direction. And it was the ones that the Cherokee had chosen for reasons of the energy of that particular type of stone.

It was a private place. You couldn’t see it from the house and classroom, but it was a short walk. That’s where we had circles unless the weather was real bad. Then we would use the classroom, but usually it was do-able, and we could have a fire in the middle. Most of the time, we got to have them outside.

ES: It was an assortment. Oaks, pines. In the circle, a certain kind of tree was on the north of the circle. That was all intuitive.

ES: We usually did candles. It would often be after dark, except in summer. A lot of women wore long dresses and robes, but it wasn’t required. And it would vary. Hallowmas was probably the biggest time with all sorts of wild robing.

ES: But all indigenous people around the Earth had so many similarities with their spirituality.

ES: Absolutely. Or developed across the ocean. They are basically similar. It all went together well. We didn’t say it was strictly Native American at all. Whatever research women did, or what was their ancestry, was wonderful.

ES: We did have some basic things that we did. We always called the directions. And we had everybody call in any spirits they wanted, dismissing them at the end, or saying they could stay. Always as a part of the circle, somebody would do some sharing about what’s been going on for hundreds of years around the world, some background on how we are connecting to the past. Then it would really depend on the season, such as fall, the autumn harvest and the going in, taking the theme from that, whatever things people thought would help them take that in and focus on that. We almost always did a healing circle on everyone there, calling out names and sending healing energy out. Healing was always a big part of it. It wasn’t rigid. Those are things we did want to put in each time.

It was for me, and for some. I could feel . . . call in people. A key woman in my life was my piano teacher that I started with in first grade. Much later, I found out that she was a lesbian. She taught at the university that was in the town and developed a program to teach teachers how to teach piano. I was there when she first came, and I got private lessons with her, hour-long lessons. As I got into junior high, gradually, half the lesson would be talking about life. She was kindly teaching me very liberal ideas. It was wonderful. We were very close in many ways. This was in Bloomington, Illinois. Periodically, she would go to Chicago when some famous woman pianist was doing a program. When I was in high school, she got permission from my family to take me with her to Chicago. We also went to art museums and various things. That was really special. I think it was during my junior or senior year of high school when one of the student teachers became a regular on the staff. The two of them were close, and then, they began living together. I still didn’t know she was a lesbian, but I knew that was an important friendship for her. One day, when I came in for my private lesson, she was in tears. I asked why, and she told me the other woman was going to be moving to New York, that her family said that she could not live with a woman. They had arranged for her to marry a man in New York. This was in the ‘40s, toward the end of the war. They both were heartbroken. The fact that she could share that with me . . . but I still didn’t think of it as a sexual relationship. They were good friends. Women know how to be good friends, and I knew that was important to her.

She opened my eyes to question so many things. It wasn’t any direct instruction to question things. It was just her attitude to life, her way of looking at things, added to some other things. I was not a typical high student by any means. The boys who asked me for dates were not the cute, macho types. They were the ones who were probably gay, the artists or writers. That was wonderful. I didn’t have a crush on any of the others. I thought in high school that having a crush on women was normal for women. Even with this teacher, I still didn’t know it was truly an option. After the second world war, as I was finishing high school, there was a big push for women to get married and out of the workplace so all the returning soldiers would have jobs. The only way a woman was going to be happy was to get married and have a bunch of kids. That message came from everywhere, and I believed it. Unfortunately, I loved kids.

ES: Yes. [She points to photographs in the room, her children at different ages.] Three boys and I finally a girl. The two older ones were a year and a half apart. Then four or five years went by, and the last boy and the girl were fourteen months apart. That worked pretty well, since you could handle two. By then, the two older ones were good friends with each other, and they helped when the younger ones came along.

RN: Is that your daughter with her kids?

ES: She doesn’t have kids, by choice. I was involved in the women’s movement as she was in junior high. She came to all these things with me. She knew she had a choice. She’s incredibly bright. She went to an unusual small college [New College of Florida], where she learned about computers very early. Shortly after college, Microsoft flew her out to California, and hired her. She has lived in San Francisco [California] all her adult life. She’s really much more into nonprofits, not making a bunch of money, and into politics. They kept saying she would move up and be a vice president. She’s really good with people, a good organizer. She did get married. He didn’t want kids either. They created some unusual photography, and she runs the nonprofit they’ve had for about ten years. They go to museums and teach them what equipment they need and how to use it so that if someone steals something, this photography will show it. They travel around the world doing this. It’s called CHI [Cultural Heritage Imaging, http://culturalheritageimaging.org/About_Us/CHI_Team/carla_schroer.html. “Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) drives development and adoption of practical digital imaging and preservation solutions for people passionate about saving humanity’s treasures today, before they are lost.”]

It makes me feel so good that she turned out that way, and these things are important to her. I must have done a good job. The same with my sons. None of them are in business to make money. One is a musician, another is an incredible artist, and sculptor. They both get by financially. The youngest son and his wife teach in a special education school in Jacksonville [Florida], and they’re always reaching out to kids that need help. I’m so proud of all of them. It makes me feel that I did good as a parent. That’s what I wanted.

My daughter was here for a week recently. She’s really concerned about this crazy health stuff. She’s into alternative healing and organic foods.

ES: It could be, probably. I need to ask around for who does it. I’ll take all the help I can get. A young woman was through here recently who does a lot of hands-on healing, and it was helpful.

ES: Initially, Z Budapest’s book [Grandmother of Time].

ES: Yes, and some since then. They all had such great ideas, and I would share them with women new to the circles.

ES: Yes, and we became good friends. She came and helped us set up a sweat lodge at Starcrest. She taught and then gave me permission to do a pipe ceremony. I was really kind of scared about that awesome . . . She had gotten to know me. She trusted my intent and my ability to run a sweat lodge, and to be honest with their concepts of it.

ES: That part of my brain is so fogged [the part that remembers book titles and names]. I went to a workshop in upper Indiana or Ohio with someone who published some neat, really cool books, and I can’t remember her name. It was really great, and about spirituality and women. I remember her books talking about—she may not have used the word matriarchal, but they were mixed at best. There was not patriarchy until the Europeans came over and changed that. The books were interesting in covering the kindness, the importance of aging, how much we learn every day of our life, and how they value that. One of the things that she was alarmed about at her workshop was that the young people today are missing that opportunity of learning about life and important things from older people, and they are discouraging older people from even remembering.

There was a woman who did workshops and a book about body symbology. She was not Native, but she studied with people around the world about healing and spirituality. I went to one of her workshops and studied her book. I ended up doing a similar workshop one weekend in South Carolina. It was about understanding that if something wasn’t functioning well in the body, where it is in the body is a clue to something that is not going well in your life, and the body is trying to get you to look at that. Once I learned that, I would know what kind of questions to ask people in the healing center. It was amazing. It just rang so true.

Somebody was having problems with their right knee and thinking about getting a knee replacement. The right side of the body is male, the left side female, generally, connected that way. Knees and lower legs tend to be siblings. I asked if she had a brother and how they got along. She had an older brother who sometimes was OK, and sometimes so mean. So I asked what was going on in her life that might remind her of him. She realized she was being snappy with people, like her brother would be with her when she was littler. As she changed that, and began to look differently at herself and at others in those situations, there was much less stress on the knee.

I knew another woman who had breast cancer. She was given just a few months to live. I think it had metastasized, but it started there. The breasts have to do with nurturing ourselves. The left side in particular is a woman. I remember asking her how she nurtured herself, or did she even, and she got to realizing that she had been taking care of others for years and years. She was probably in her fifties, and she hadn’t nurtured herself. She began changing things, and came to me later to say that, though she didn’t expect to live much longer, “It feels so good the way I’ve learned now to give to myself. I’m getting to do that before I die.” It was so moving. She said, “It’s OK if I die. It feels wonderful. It’s changed my life.”

That concept that this woman developed, and her way of teaching it was . . . you don’t know exactly, you just know kind of. You’ve got to, sometimes by doing a meditation with the person, if they don’t easily think back. It’s often from childhood.

ES: I think in Jacksonville, we were still as feminists feeling that we needed to stay hidden. There was so much anger toward us that we didn’t publicize that. When I came up here, and it was mostly women I was meeting that were pretty alternative, they could spread the word. And as I did healing classes, that was an ideal group to spread the word and tell friends. We didn’t post anything about circles. It was all word of mouth. It started first with lesbians who knew other lesbians, and they didn’t have any group that met regularly. These were people living out in the country and in little towns. That was an easy group to begin with. Then women they knew got the word, so it was by word of mouth. I’m thinking about the woman who taught at the Baptist college. She had a PhD. She must have heard of it through a friend of a friend. The Methodist minister I could understand. It’s a little more open there. A professor who taught religion at Clemson [Clemson University in South Carolina] came regularly.

ES: Well, in this section, because it was little towns, the conservatives weren’t that much in control. You don’t have the control in rural areas and little towns that you do in a city, even a small city [like Jacksonville]. Anderson, South Carolina, was the biggest town in the area [population 27,000 in 2014]. The university being there maybe made things more accepted if you’re weird. The shaman working in the police department later told me that the police department had heard that we were doing circles, and that meant we were killing babies. So they sent a woman to attend, and she went back and told them that it was nothing like that. She told them that it was about women supporting each other. But this shaman in the police told me that there was a Satanist group that met in the area, and that they had killed a baby or two in sacrifice. Apparently, there was. One time, I got a phone call from a young man who told me he was going to that group, and that he wanted to get out. He was afraid the police were going to come to get him. He wouldn’t give me his name, out of fear, but we talked a little bit. The police said that they finally found and arrested the leaders. It was mostly men.

February 29, 2020. Community House, Alapine Village, Alabama.

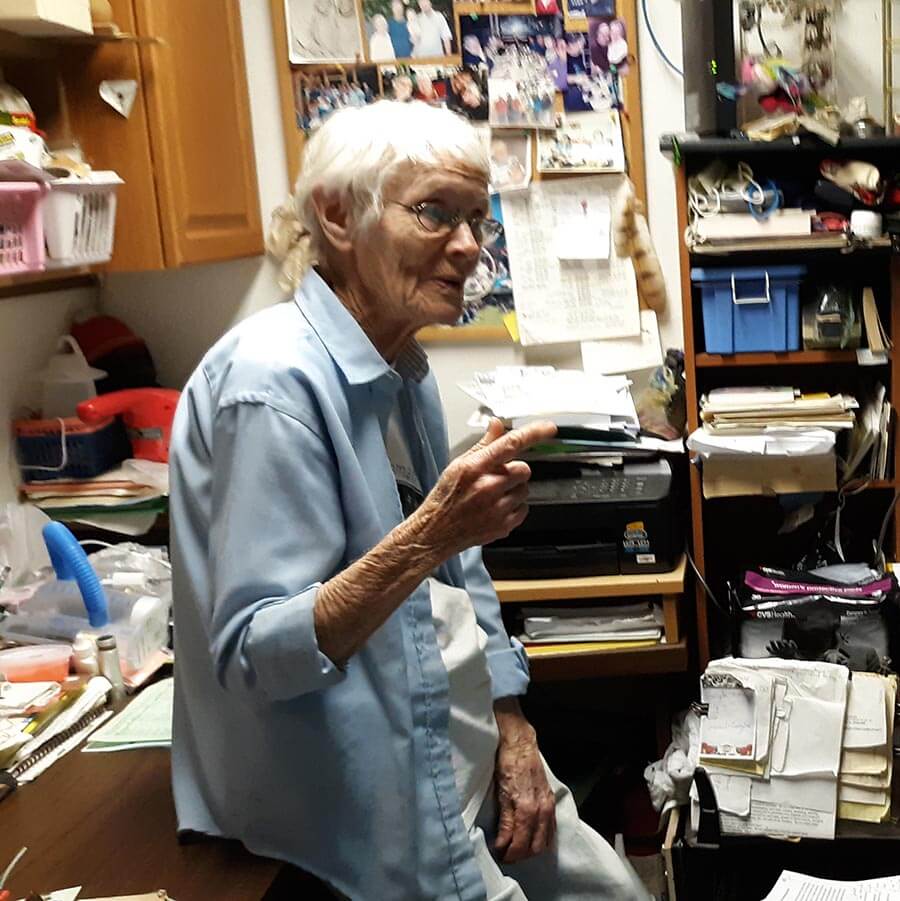

In this followup interview, Ellen Spangler is joined by her life partner, Mary Alice Stout, who became part of the Starcrest project.

ES: The Methodist minister came and actually got involved in some of the other classes about intuition, and really, with things that I had learned from Native Americans, intuition and being open to those messages. I asked the clients, and they said that I had to keep teaching that class. I said, “What shall we call it?” They said to call that Psychic 101 and we want Psychic 102. And she came for these.

She was actually at a church. I was out in the country. It wasn’t as if her neighbors would know where she came for these things. After two or three years or so of being involved in women’s circles and some of these classes, she came out as a lesbian. When I first worked with her, and she did some individual work, she didn’t know she was a lesbian.

Mary Alice Stout: About my age

ES: Yes. At that time, she was in her 50s or late 40s.

ES: Well, what happened with her is that she could give herself permission to discover who she was and what she really wanted in life, and not have to do what she was told. She probably loved women all along, and she thought that would have been really bad.

MAS: She had been married and had a child or two.

MAS: She had gotten divorced, and she has passed away now. We were talking about her one day, and I said, “Ellen, I’m going to Google her name and see if she is still where she was before,” and I found her obituary. I’m trying not to say her name because we don’t have her permission.

ES: Another woman, middle-aged, Nancy, who taught religion at Clemson University, got involved in women’s circles, and then also took some classes. She was a single woman, but really liked the whole concept of women’s circles and of what comes out, and intuition and spirituality in not dictated forms. She taught religion, like I said. So one time she was going to have to be gone for a whole week or something, and she asked me to teach this one class. I think they may have been freshmen. She was really concerned with religion, and that there was so much negativity in the class. Even the word “ritual” to most of them in the class—they thought that was evil, that you can’t use that word, that it means something bad. So she asked me to focus on that word and talk about how there are all kinds of ritual. You do rituals of all kinds in your life. Anyway, to get them to not be looking for such bad stuff about it, that was what was really fun.

MAS: I recall you talked with them about birthday parties, and how that was a ritual.

ES: I did. And Christmas. How does your family celebrate Christmas? What do you do? I was really able to get them to see that we do rituals in all kinds of things. You could do them for very hurtful things, or you can do them for very positive and growing things. Anyway, it was really fun. She said that if she had presented it to the class, it would have been dealt with differently. She said they were changed when she came back. I was really pleased.

MAS: Didn’t one of them talk about the death of a dog, and the ritual they created around burying the dog? They started joining in with Ellen.

ES: Yes. I was there for two different classes that week, and by the second one, they had thought about things, realizing that what their family did when a pet died was a ritual.

ES: Yes, and how helpful it was. I opened Starcrest. This is before Mary Alice and I met.

MAS: And they had that store.

ES: And I was ready to leave Florida. It was getting too hot, and I was already reading about climate change, and I had come up to help these friends that were creating a farm, a goat farm, actually. I really liked the area, and I liked the climate there, the more moderate climate. That’s why I ended up there. Also, at that time, I was doing a lot of traveling out West, and connecting with Native American women who were doing workshops or published a book. I was very fascinated by the more ancient, native spirituality, and by how much sense it made. And in the process, it kept me changing and realizing how important intuition was. Our culture puts that down so, doesn’t let people tune into their intuition. I’m sure in some of the workshops I went to that was dealt with, and that I was much more open.

Also in Florida, Kay Mora arrived down close to the Pagoda. [Kay Mora (1928-2003) was a professional psychic who built a beach house close to the Pagoda and partnered with a Pagoda woman, Jean Adele, who later moved to Alapine, Alabama.] That’s before I had moved, and she’s who probably first opened my eyes more in this direction. I took her classes, and it was amazing! Like in the more advanced class, she said “OK, we’re going to do some trance work. You might not do it, but we’re going to try.” I was the only one in the class who went into a trance, and I immediately—I was gone. And it scared me [laughter]. She said she wanted to work with me individually because I did it too easily, and I could be off somewhere too long.

ES: I probably did, because I was seeing strange lights. She began to work some individually for me, because she said it’s such an important thing to be able to do, but you want to do it safely. And she said I should always have someone with me who will count me down and knows how to count me back.

ES: I did that.

MAS: Once a month.

ES: Yes, I was not comfortable with that, as opposed to just meditation with a class and so forth. Because when you really do go in a trance, you lose complete control of what you’re saying and all. And I’ve always had that control. That was scary, and I only did it with people from the class that would ask specific questions. I did it once a month with somebody who would count me down. They would ask the questions, make notes, and talk to me afterward about things that…

ES: Yes. Basically, one of the things that Kay Mora started me on (and some of the Native American women encouraged) was whatever this incredible energy is up here, whatever anybody calls it, you can call it “God” or angels or whatever, but you need a kind of visual of what yours is because you communicate more directly. When I was still working with Kay Mora, she asked one of the times if that energy would personalize or identify itself, and it was this Native American woman that had rainbow colors on, seven colors. As that progressed, it was the seven chakras, the colors of each of the seven chakras. Given some time, each one—it was really a group of seven—she was the seventh, she was the combination of all. One of the things about doing it that way (I’m really glad Kay had me identify the identity) was because it was like a more personal connection. I could talk to the green and picture and ask questions that had to do with heartfelt things, or things in that area, and I think go into a deeper place to really hear that, not so colored by my own intellect. That’s a key thing in doing this kind of work. You try not to let your taught knowledge answer the question. It might be the same. So, I did it because I felt safe enough with that group and with the students, that there would be one particular person who would be responsible to count me down and count me back.

The thing that moved me into [into trance work] was I realized how much that brought to me, and I wanted –what my classes basically were was finding ways to teach and encourage people to let go and touch into their intuition, to really learn to trust it more. To try it out, how do you do that? And what are your fears about doing that? For most of the ones who had trouble doing that, their fears came from some kinds of abuse as kids, in the family or out. Usually within the family. I know in some of the things I read and even some classes I took and all, that it talked about how as children, we are initially so open, and it’s why sometimes little kids tell these stories about who’s been in the room and so forth. It’s really that intuitive thing, but that gets discouraged. Usually we’re told, “That really isn’t so.”

MAS: Like the kid that was talking when the lady was pregnant, and he was talking to the birthing angels in the room. I remember that.

ES: Yeah, and so most of us got that “taught out of us” so to speak. People wanted some individual work. They were stuck somewhere, and I began to do a kind of counseling. But it became inner child work, because that was mostly…it was before “inner child” work was even– that word was not out and about. This was like 40 years ago or so.

ES: Yes, right. I found that I could get people to really let go with meditation. Most often, for instance, if there was something they’re struggling with right now, I’d say, “OK, just look back at your growing up, of when you felt the same way, or when something similar was happening.” Right away, something would appear and they would begin to describe it to me. And I would have them talk with that child and begin to help that child not be so afraid or closed or whatever. It was very effective with most people in moving through difficult things that they felt stuck in. But part of that was also . . . usually it was people in class that were beginning to open up to that, that would then do some individual work. In the evening class, we would do meditation and do some sharing, but for most people, going deeper needed to be just them with me rather than the group; that would be difficult initially.

All that really went along with the women’s circles that I learned about in 1976 in Boston. It was the first national women’s spirituality conference. Three of us from Jacksonville, Florida, drove up. We had read about it in a newsletter or something, and it was incredible. It was in a building downtown that had at one point been a big old hotel, and then was a piece of the University there that they rented for the weekend for workshops. And, oh goodness, some of the names of the women publishers and spirituality were all there teaching. I can’t think…this brain…

ES: Oh, yes, she was there!

ES: I don’t remember if she…somebody who wrote great books about the Christian church and how base it was and…I’m trying to think, she was there. [It was Mary Daly, she later confirmed]

MAS: You know we had a bookstore at Starcrest, too, and we sold some of these books. There were not many books authored by men. Most of them were women.

ES: Anyway, it was such an eye opener. And to go to these workshops and hear the changes it made in people–and it just validated things I was already learning from Native Americans and so forth. One of the big events they had there was at a big church close by. They had made arrangements one evening with that church. The event was packed, with standing room only. Everybody was to go home encouraged to begin doing women’s ceremonies, especially on the key times of year, the equinoxes and the solstices, and really go with the Earth. There was a lot of focus on taking care not just of ourselves but of the Earth.

ES: Yeah, it was an incredible conference.

I came back to Jacksonville to the women’s movement, which was pretty strong there, and there. Many of them there were really excited about what I said. We started doing women’s circles . What they had encouraged in different workshops was that you find things to read from different cultures all around the world. You can also tune into yourselves, and don’t make it so compacted you can publish a book on what you’re doing. Because the idea is you are trying to bring things from the heart and promote healing on all levels of yourselves and of others and the world. It was a great inspiration. We did circles and that grew…

ES: I was really connected to the Pagoda, so I came back. They really were interested. Kay Mora—had she been there then?

ES: No, she wasn’t.

ES: Then Kay moved in to St. Augustine.

ES: Yes, but she was there a couple of years before then.

ES: Yes. And that of course all fit in with women’s circles and developed what’s really spirituality. It just meant so much to me, and I could see with other women how it did and everyone was encouraged to try to get a group going wherever you lived and begin creating some of that energy.

ES: Right. That was later then. It was about 1984 that I moved up there. So I already had been working with women and we had been doing women’s circles.

ES: Yes. And with them, I shared things I had learned at the conference, and whatever books I had about it then, too, like the Z Budapest book, and I don’t remember what others. They were really pleased, and they moved in that direction quickly.

ES: It’s that kind of pointed corner of South Carolina, the northwest section. Mostly small-towns. Clemson University is there, and Anderson, another small town.

ES: Yes.

ES: Yes. And this isn’t, I mean, there are a lot of similar things to Wiccan circles, but we’re not. . . the goal is not to pattern it specifically after that, or specifically after Native American, but to keep it open to those ideas, that sharing, and that connection in a lot of different ways. In fact, in South Carolina, then, we would have 40 to 50 women to come for a circle. Shortly after that got going, I said the planning needs to be a group, and asked who was interested. I think both the ministers I mentioned earlier said that they wanted to be part of planning. There must have been six or seven, [turning to Mary Alice] I think this is still before you moved.

MAS: No, I was there. Yes, we had Marty, who moved to St. Louis [Missouri]

ES: I could just be a part of it with ideas, but I wasn’t the minister.

MAS: It was good to have them.

MAS: On April 1. I remember that. Are the circles still continuing? I know the sweat lodges are.

ES: I know the sweat lodges are.

MAS: And it all kept going

ES: And it was based directly on Native American…

MAS: on Lakota…

ES: And they really followed their format, to be respectful of that. But it was another group of women, not lesbians. I mean, all women were invited to that. It was similar in many ways. In terms of what happened, what you felt like, the spirituality. Yet in a different format. It was also very loose, not scripted.

ES: We were taught by Beverly Little Thunder. We had made friends with her.

MAS: You had made friends with her years ago. You were visiting your sister.

ES: Yes, actually, it was the summer that Mary Alice and I met. I was coming back. When I went through Knoxville, Tennessee, and a friend of yours that I had met at conference…

MAS: And I thought that she [Ellen] was weird!

ES: Because of the things I did. [laughter]

MAS: I had work to do. “I’ll eat my sandwich, meet her, and that’s it. This woman is weird.”

ES: You came with the group and…

MAS: …had to get back to work.

ES: When I met Beverly Little Thunder, I was just open to exploring, especially to Native American things. My sister lived in Phoenix, Arizona, and she raised her kids there. When she and her husband would go off for a period of time, they had at least one cat and one dog. Somebody would have to house-sit to take care of the animals. They had a big house. I had let her know I wanted to travel that way, and she asked me to come. It was in the summer. I’d have a place to stay, it wouldn’t cost me anything, and it would be great for them. I immediately went to the women’s bookstore to find out anything that was going on that was feminist or lesbian. There was a lesbian gathering, I think it was toward the end of the week, and it was going to be on Saturday. I got somebody’s phone number, and I called to get directions.

I went to this group, and I said, “Are there any Native American things going on?” The summers get kind of dead in Phoenix. And they said that there was a Native American Sundance, women, happening. They gave me a phone number, but they told me that since I’m not Native, and they don’t know me, that I might not be welcome. I told the woman I talked with a little about me, that I really wanted to learn, or I had learned some from the Native women, that I had done some studying with, and reading, and that I was really impressed with their spirituality. Could I come and help in any way? I’d help in the kitchen. I’d help because it’s a week-long gathering. She gave me all the directions and the information. She told me things they would need, like to bring a lot of gallons of drinking water and food. But she said, “You might, when you get to the entrance, they might send you away.” And I said, “OK, I’ll be prepared.”

MAS: Wait. Tell the directions that you got.

ES: The place was a couple hours from Phoenix, and I ended up on this little, two-lane, paved road. They had said, “You go through this little town of whatever the name was, and then you’re on a kind of higher level of the desert. You look for these worn tire-tracks going off to the left, with nothing that goes down. That’s what you want to turn on. If you get to this next little town, then you’ve gone too far. Turn around and come back.” Well, I saw the tire tracks, and sure enough, once you kind of got over this hill, there was an encampment, tents, and that was it. The woman who was the entry person, she and I talked. I told her why I was there, and she said, “We could use more help.”

I had turned 50. Age and wisdom, with Native Americans who had been brought up in their tradition, are very respected. Different than our culture. Especially women’s age is highly respected. And in fact, in one thing at the closing circle, another woman who was in her 50s made sure that they had all of us who were 50 to stand, and they did an honoring. I always noticed with Native American women how respectful they were to older women. They wanted to hear anything we said. Not “Oh, she’s just an old lady. I don’t want to hear her,” which is so much more the attitude in our world.

When I got there, I drove in and parked (I could stay in my van). I met someone, and I said, “I’m willing to work in the kitchen. Or what do you need?” And one of them said “Oh, yes.” They might be able to use a little help. I could come to help carry some of the food stuff that was prepared at some of the different places. Then somebody else told Beverly Little Thunder. Beverly was one of the key directors of this Sundance. There must have been 60 or 70 women there. Not all Native women, but friends of Native women, too. And I had said to two or three people asking what I was good at, and I told them what I did. I said I did hands-on healing, and that I was willing to do anything they needed. I did carpentry and other stuff.

Somebody perked up and said that one of the women dancers was needing healing work. She was struggling, and they asked if I would be willing to come and work with her. They ushered me into the tent with the dancers, which was, I mean, I felt so humbled. And I did work with her throughout the Sundance, three days of the dancing. They danced in the heat of the day. If I remember, they danced for something like an hour, and then there was a break, and then…anyway, I was able to help her some. She managed to do it. Once I began working on her, some of the other dancers said, “well, I’ve got this problem. We’re on break, can you come and…”

ES: But Beverly Little Thunder was very closed, and she didn’t want help. She said, ”I don’t need any help. I’m fine.”

After it was all over, the last day, there was this big ceremony, a gathering together after the dancing, the singing, the chanting, and the sweat lodge in the morning first thing, which I was required to do, too, to be able to work, which I wanted to do. We had done sweat lodges every morning, but that last day, whew! It was intense. I mean, it was so hot, and we had to sit up tall, and there were no breaks. Anyway, but that’s OK. It was a good experience. So that last day, some of the dancers came to me, and they said, “Beverly really needs some healing, and I know this is just her, but we’re going to insist to her that she let you do some healing work. You’ll notice she’s not going to be real welcoming. But we’re insisting.” Well, once I starting working with her, she took away her fears. We really made acquaintance and wrote to each other.

Beverly Little Thunder is a two-spirited Lakota Elder from Standing Rock, North Dakota. She currently lives in Vermont and works with the Peace & Justice Center there. See her oral memoir One Bead at a Time (Inanna Publications, 2016).

MAS: She still writes to us.

ES: Yes. I was out there again. Over time, we became friends. And of course, Mary Alice met he.

ES: She did, yes!

MAS: She sent us instructions of what to do to have a properly constructed sweat lodge in the traditions.

ES: No.

MAS: We had to put it back together every now and then.

ES: Yes, I mean, you cut down the skinny trees that make the round shapes, and tie them all together with an opening. Then, blankets go over…

MAS: But the blankets didn’t stay. We would dry them on the clothesline and put them back in a cedar trunk.

ES: And they wanted the blankets to try to be natural materials, cotton or wool, not synthetic or polyesters. And firewood needed to be found. Oh, and how much space you needed to cut trees, and to clear the land, and…

MAS: How deep to dig the hole, how wide…

ES: Right, for the fire in the middle. And which direction, I think the door was to the east.

MAS: So we had everything almost ready when she got there.

ES: And then she came.

MAS: And I told her the truth, that we had used the sacred rototiller to dig some of the hole.

MAS: She said as long as it was the sacred one, it was OK. And then, we went to Elberton, Georgia, with a group of the women. They do granite monuments for headstones there, and we had located the dump where they threw away the scraps of stones. We brought back shaped and colored pieces of marble and granite for our stones. And then we had local, quartz rocks there, too, that could go in to get heated. Beverly was very entertained with the rock shapes. Some of them were pink triangles. I think we still have one of those at our house.

MAS: No, Ellen moved it to the property.

MAS: No, no, no. We built on to it, but the original house…

ES: Before her, I had cleared and I had seen this older house that was structurally in excellent condition. I bought it for nothing, and I paid movers a lot to move it.

MAS: The next time we are together, she needs to tell you the story of the house.

ES: Because there was a piece of it that kind of dropped. We had to do some repairing.

MAS: We sold it to the neighbor.

MAS: Well, we sold it to her partner. It was a goat farm, Split Creek Goat Farm. To Evans and her partner.

ES: And her partner wanted it for her daughter. Anyway,

MAS: She wanted it for her art studio.

ES: That was it! It was great.

MAS: They let that continue up the hill, but now the circles and stuff, I don’t think those continued there.

ES: No, the circles could be anywhere. But the sweat lodge was there for a number of years. And then the key woman who really kept them going got to know Beverly Little Thunder. Beverly was living out in the West when I met her. She moved to the northeast, and she was doing sweat lodges in the summer there. That South Carolina woman would work with her in those summer sweat lodges in the northeast.

MAS: She got on the women’s council of the sweat lodges.

ES: At some point, she moved the sweat lodge to her property, which was out in the country, because it was just getting too hard. But for a number of years, the sweat lodge continued right there [at the Starcrest location].

MAS: We never called them Moon circles. We called them women’s circles.

ES: Women’s spirituality circles, if you wanted the whole name.

MAS: Sometimes there was a full Moon, sometimes not.

ES: I know they continued for a while. And the last one I think that we had was a croning, and there were 76 women who came!

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Jessye Ina-Lee, video interview with Ellen Spangler and Mary Alice at their Alapine home in Alabama, Lesbian & Landdyke Documentary Media Project, 2005. For information, contact email jaehaggard@gmail.com, see website www.womenearthandspirit.org, and postal mail address: Women, Earth, and Spirit, PO Box 130, Serafina NM 87569

Pagoda Women at Alapine, audio recording of an interview with six Pagoda women, including Ellen Spangler, recorded April 13, 2013, online at Duke University, https://repository.duke.edu/dc/slfaherstoryproject/04568a3f-87e0-4dc2-bfd4-44b8cebd1eb8

Rose Norman, “Ellen Spangler and Starcrest,” Sinister Wisdom 124 (Spring 2022): 67-72.