Rose Norman: Finding Lesbian Community in Alabama

Interview by Merril Mushroom via Zoom on November 14, 2023

Merril Mushroom: Where were you born, where did you grow up, and what was your family like? What did you do before you moved to Huntsville, Alabama, and why did you move there?

Rose Norman: I’m from Alabama. I grew up in a very small town near Montgomery. I remember the sign as you drove into town. It said, Fort Deposit, Population 1,352. I think that was from the 1960 Census.

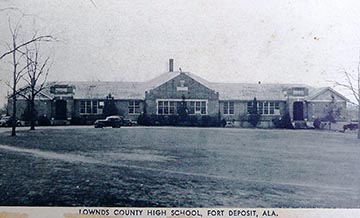

I went to one school that covered grades one through twelve. My first-grade picture has the caption under it saying “Lowndes County High School” because that was the name of the school that included all of the grades. It was segregated in those days. The population of the county was 70% Black. [In 2020, it was 76.9% Black or African American.] Until the 1960s, I was not really aware of the extreme discrimination against Black people around me.

I’m from Fort Deposit, Alabama, population 1352, the biggest town in Lowndes County

MM: What happened that made you aware in the 1960s?

RN: Fort Deposit is in Lowndes County, Alabama, and it became a hub of a lot of civil rights activism. We had a lot of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) volunteers coming in to work on voting rights and to try to register Black people to vote. There was a lot of racism—and a lot of pushback from white people.

This area is very poor and rural. Fort Deposit is the biggest town in Lowndes County. The county seat is Hayneville. Hayneville became notorious because of a murder in broad daylight. A white, Episcopal, seminary student named Jonathan Daniels, along with a white Catholic priest and some Black, SNCC activists had been arrested in Fort Deposit. They were jailed in Hayneville. Daniels was shot and killed in Hayneville. The Catholic priest was shot, too, paralyzing him.

The murderer was acquitted of manslaughter. My brother recently told me that my father was on the grand jury that indicted the murderer, Tom Coleman. The murderer was the brother of the Lowndes County Superintendent of Education, and he was kin to a friend of mine. My brother said, “It was a miracle that they even indicted him.”[However, it was not surprising that he was acquitted.] That’s how racist it was in Lowndes County.

I knew none of these details at the time. In recent years, I have read and learned about it. All of the activists had been taken to Hayneville and put in jail there because it was thought it was not safe to jail them in Fort Deposit. That Fort Deposit was considered unsafe amazed me. I felt totally safe in Fort Deposit. For me, it was all white. The few Black people that I knew then were maids or janitors or truck drivers. I knew no Black person as a friend.

This happened in 1965, my junior year in high school. That same year, Viola Liuzzo was murdered in Lowndes County. She was a driver for the famous civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, and a Black man was in the car she was driving. A carload of racist men, including an FBI informant, drove by and shot Viola Liuzzo dead. That still haunts me, that it could happen in Lowndes County. It was in north Lowndes, and we lived close to the southern end of Lowndes County. Somehow, I convinced myself that things like that didn’t happen in Fort Deposit. They probably did.

There was just a lot of violence that you couldn’t ignore. It was on national television. I learned recently that my county was known among civil rights activists as “Bloody Lowndes.” Last year, I watched a PBS [Public Broadcasting System] documentary, called Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power. I thought I would recognize people, but I recognized no Black people and only one white person. The whole story of voting rights activism in my home county was completely new to me.

I can’t say that any of this made me an activist. However, I did work for Head Start the summer after I graduated from high school. [Head Start is a government-sponsored summer program offering early childhood education, nutrition, and healthcare. It started in 1965.] I was a teacher’s aide. That’s when I got to know Black people in a different way because all the kids in the class were five-year-olds, and all of them were Black.

Later, I worked for another summer program called DISTAR [Direct Instruction Reading Intervention Program], where I was a third-grade teacher, and where those children were all Black. Both programs were at the Black elementary school. Before that, I could not have told you where that elementary school was located.

I also worked one summer for something called the Job Corps. We drove all over the county, walked into very poor people’s houses, and wrote down things about them. All this was a revelation to me. I had been very sheltered and very privileged. Even though we didn’t have a lot of money, we were privileged just because we were white and middle class.

Many white people would not go near the Head Start program, let alone work for it.

MM: White! What did you think about all that when you were finding it out?

RN: I thought that I should do something about it, but…

MM: Why did you think that?

RN: It was clearly wrong, what was happening. It was wrong the way people were treated. My family were what passes for progressive in a small southern town. And very religious. The Baptist church was the center of our social life (my parents also played a lot of bridge). Everybody I knew went to one of the three churches in town: the Southern Baptist, the Methodist, or the Church of Christ. There was also a Presbyterian church somewhere out in the country. These were all-white churches. I still have no idea how many all-Black churches there are.

I think my parents’ attitude to racism came from Christianity although their culture certainly taught them that Black people were lesser, and that they were not to be trusted. Lots of racist things like that. That doesn’t sound very progressive, I know. Maybe “tolerant” is the word I’m looking for. Many white people would not go near the Head Start program, let alone work for it.

One of the white teacher’s aides in the Head Start program went to our church. Her husband was fired from his job because she was working for Head Start. In turn, my father hired him to work at our store. That was another part of the privilege I lived in. My grandfather had owned this store, and he was a very successful businessman. My father worked there most of his adult life; and he came to own it with his siblings when my grandfather retired. My father hired that guy to work there, and some people stopped coming to the store because of it.

By that time, in the late ‘60s, discount stores were changing the retail business. Interstate 65 was built the year I graduated high school. People who used to shop in Fort Deposit were going to Montgomery to shop. There was a time when this little town of Fort Deposit had four car dealers, a tractor dealer, five grocery stores, and several dry goods stores. It was a very thriving, retail business center for the area. Our store was the biggest store in town. We had hardware and groceries and dry goods. I worked in the dry goods section as a clerk. We also sold building supplies and fertilizer, and there was a cotton gin. Today, it is practically a ghost town. There’s almost nothing downtown. Our store is now a vacant lot, as is about half of the main street in town.

MM: Did Black people come shop in your store, or were only white people allowed in your store?

RN: I would say that Black people were our biggest customers, outside of the big farmers who bought farm supplies. That may have been partly because we offered in-store credit.

MM: Was there a problem about that, among the local people in the town, because you allowed that?

RN: Not at all. I think that Black people shopped all over town. There may have been certain stores they didn’t go in because the proprietors were really racist. There were some remarkably racist people in town. I don’t really know about that aspect. The population was 70% Black, which means most of our customers are going to be Black.

My grandfather also had a factory. He and some partners started a pajama factory, Fortex, where they employed a lot of Black people and white people. They were, I think, the biggest employer in town. A lot of factory workers would come to the store, because there was a special arrangement for them. Probably, it was like the “company store,” where they took it out of your paycheck or something if you wanted to buy things as a worker there. I don’t know. A lot of our customers worked at Fortex.

MM: Was there a separate school for the Black kids besides the Head Start, like an elementary and high school? Or did they have to go far away out of the county to go to school?

RN: Oh, no. Fort Deposit Elementary was all Black. Lowndes County Training School was the high school for Blacks. Both of these were much larger than Lowndes County High School. Hayneville also had a high school, and they were our chief rivals in football. Lowndes County High School integrated during my senior year. My class had one Black student. There were a total of ten or twelve Black students that year in grades seven through twelve.

MM: How did that go?

RN: It was okay from my point of view. There were families who picked up and moved away because they didn’t want their children to go to school with Blacks. Also, some white students came to Fort Deposit to Lowndes County High School because of integration problems in the Hayneville school. We had several white students in my senior class because of that, who had never been in school with us before. One of my white classmates got sent to a military school to finish. Some of the people who opposed integration started a private school for white students, Fort Deposit Academy. This tiny town had a private school. It made no sense. My parents didn’t have anything to do with that, ever.

I had three younger siblings who stayed in the integrated school for another eight years. My brother, who is eight years younger than I, was in the last class to graduate from Lowndes County High School. The building is now Lowndes County Middle School. After that, my youngest sister went to the private school in Greenville, a much larger town in the next county. I don’t know the details of what was happening then, but my parents didn’t think our school was safe any longer. I don’t think they thought much of the quality of Fort Deposit Academy either. It lasted until 1986. By then, I was gone. In fact, I never intended to come back to Alabama. I just wanted to get out.

MM: Because?

RN: I wanted more, you know, something different. Alabama was just not where I wanted to be. Of course, I went to college in Alabama. I went to Judson College, a small Baptist women’s college where my mother and all my aunts had gone. It’s in Marion, which is on Perry County, another low-income, rural area like Fort Deposit. Coretta Scott King is from Marion. I really liked Judson College.

MM: What did you like about it?

RN: I think it was the step-sings that created an emotional attachment to it. Every class had a song leader, and every Saturday night we would gather on the grand staircase inside the main building to sing. It was a really small college, with 300 students, the highest enrollment they ever had. I liked the teachers. We got a lot of individual attention from the teachers, and we knew everybody. It was a lot like Lowndes County High School, where we knew everybody.

MM: What did you study?

RN: English. I never had any interest in anything else. I just wanted to read books, you know. I had crushes on teachers. [laughter] There were some really nice teachers.

MM: After you graduated?

RN: I didn’t know what I wanted to do. At first, I thought I wanted to do journalism. They didn’t offer a major in journalism at Judson College, only English. I had one journalism course. At that point, I didn’t think I wanted to teach. I thought that I wanted to write, or to do something other than teaching.

Fortunately for me, the professor in charge of my major had figured out that I should go to graduate school, helping me to get a scholarship to the University of Alabama. I had applied to some other graduate programs, and the University of Alabama was the only place I got funding. Therefore, I went to the University of Alabama, and I got a master’s degree in English. The second year I was there, I was a teaching assistant (TA), which paid for my tuition, because my scholarship had run out. By then, I thought, okay, this is the way to go. I got a full-time job teaching in South Carolina at another women’s college, Winthrop College, a state-supported college, which is now a coed university. That was a really good job.

MM: What was good about it?

RN: It paid well, the course load, and I liked it being a women’s college. I taught four classes each semester: two in English composition, two in British literature. Often, colleges require people who only have a master’s degree in English to teach nothing but first-year composition classes, sometimes five of those classes a semester, especially at community colleges. I had been making $2,000 a year as a teaching assistant. When I started at Winthrop, it paid $8,000 a year, which was a fortune! The second year, it was $10,000. I couldn’t believe it! The state legislature, I guess, voted a raise for everybody at my level. Winthrop is in Rock Hill, South Carolina, which is on the North Carolina border near Charlotte. It was a very nice place to live.

It was a two-year, temporary job, and I did that from 1972 to 1974. When I moved to South Carolina, I rented an apartment that the guy I replaced had been renting in a private home. It was his sixth, two-year job. He left to go back to graduate school. I knew I did not want to do that, to keep moving around from one temporary job to another. That’s when I decided to go back to get my PhD.

I wound up at the University of Tennessee (UT), primarily because of an academic couple who both taught in the English Department at the University of Alabama. They cooked up a class called Literary London, and they took us students to London for three weeks in the summer. We got credit for the course, three hours, pretty good. We went to plays and to every literary site you could imagine that was within a day’s distance of London. We spent a weekend in Stratford to see the Royal Shakespeare Company and Shakespeare’s birthplace. I saw seventeen plays of all kinds—except no musicals—while I was there. That was my last year at the University of Alabama, the summer of 1972.

The academic job market was crashing, and our professors were telling us at this point not to get a PhD because we wouldn’t be able to find a good job.

The couple who took us to London had gotten their PhDs at the University of Tennessee [UT] in Knoxville. When I decided to go back to graduate school, I applied at UT because the couple had loved that university. I had applied at Alabama again, as well as the University of South Carolina since I was living in South Carolina, and the University of Wisconsin because somebody in the Winthrop English Department had gotten a degree there, and had recommended it to me. In the end, I chose UT because they gave me the best financial deal.

I was pretty inexperienced about this kind of thing. I didn’t really have much guidance in figuring out what would be the right place for me to go to school. When I was at Alabama, my best teacher taught Renaissance drama, which got me really interested in Renaissance drama, and I took a bunch of those classes. At UT, my favorite teacher taught American literature, and I took a lot of American literature classes. When I met the guy I married, he was a medievalist, and I took a lot of medieval courses. [Laughter] Not the way you normally would plan your academic career. It probably didn’t matter anyway because the job market had crashed. The job market for college teaching had been, at one time, really good. However, our professors were telling us at this point not to get a PhD because we wouldn’t be able to find a good job.

My former husband is how I got back to Alabama, but it took a while. When he and I finished our coursework, and we were planning to write dissertations, we got married. This was 1977. We expected to spend another year in Knoxville as teaching assistants while working on our dissertations. We had gotten some money as wedding presents, and we spent it all going to England, Ireland, and Scotland. We spent six weeks in the British Isles.

When we got off the plane coming home, his father told him that there was a phone call for him from the UT director of graduate studies. It was a job offer at Texas A&M, a one-year job, with the condition that if he finished his PhD, it would become a tenure-track job. Tenure-track jobs were hard to get, especially for medievalists who were not at ivy league schools. And it wasn’t a medieval job. It was a job teaching technical writing, which he had done in the Air Force, his only qualification for it.

He took the job, we went out there to Texas, and I retrained as a technical writer because that was a subject where the jobs were. I got a job as a technical editor in the oceanography department at Texas A&M. The university at that time had almost 30,000 students. I think that now, it’s close to 50,000 students. It’s a really big school, and it’s incredibly well funded.

MM: Is it a mostly Black school?

RN: Oh, no, it’s very white.

MM: That’s interesting, because most of the A&M schools that I know about were for Black students.

RN: That’s true here in Huntsville: Alabama A&M University is an HBCU [Historically Black College or University]. Texas A&M is a land-grant school, the same as Auburn University in Alabama. Texas A&M is the agriculture school, and the students, known as Aggies, are looked down on by the other, big state university, the University of Texas, or “the other UT,” as we University of Tennessee graduates called it.

Texas A&M is also a very good engineering school, and it is strong in the sciences. It brings in a huge amount of grant money, which is how I found work, through one of those grants. It was originally a military school. They had about 4,000 students in the Corp of Cadets, who wore uniforms with spurs on their boots. It was a very colorful place.

MM: Very Texan.

RN: Yes, very Texan. I really enjoyed the friends we made there. There were thirteen, newly-hired teachers in the English Department the year that we went out there. Almost every one of the new-hires had a trailing spouse, a partner who didn’t have a job, and who was looking for one. Many of us spouses also had PhDs or almost PhDs. I typed, I think, six dissertations that first year in Texas, including my husband’s. That was how I was earning money. Meanwhile, I wasn’t writing mine.

MM: Did you edit them. too, while you were typing them, or just type them?

RN: Well, if I saw something spelled wrong, I would spell it correctly. I wouldn’t say I did much editing. This is typing on an IBM Selectric typewriter. The first dissertation that I typed was my aunt’s, and she paid me by buying this Selectric typewriter that had the correction key. I got really good at that. Finally, I wrote my dissertation, finished my degree, and got a better job there in College Station [at Texas A&M].

MM: What was the subject of your dissertation?

RN: Autobiographies of American women writers in the 19th century. It was not a winning topic.

MM: Why were you interested in that? What was it that turned you on about that to inspire you to do your dissertation on it?

RN: I had taken an American autobiography class from the teacher that became the professor in charge of my major. As part of the PhD program, we were required to take two outside classes in another discipline. Women’s history was just getting started, and there was a “Women in American History” class and a “Women in European History” class. I took both of those. That got me interested in feminist approaches to literature. That autobiography class got me interested in autobiography as a literary genre to study. That was the very beginning of focused research on women’s autobiographies. After that, a number of really good books came out, too late to do me any good for my dissertation.

I was very badly placed for this subject because I didn’t have anybody mentoring me about it. I was just figuring it out for myself. I remember making a copy of a bibliography of American autobiography by Louis Kaplan. I cut it up to create an index card for every apparent woman, judging by the name, mostly. That gave me a sense of the size of the territory. There were about 6,000 autobiographies listed in that book, and I found that approximately 1,000 of them were women. I began to classify them: childhood autobiography, adventures in the wild west, Civil War stories, etc.

I didn’t know I was going to write about writers. I was just going to write about American women’s autobiography, and that topic turned out to be way too big. I spent a lot of time trying to get a handle on it. I read a ton of autobiographies by American women, just randomly, whatever the Texas A&M library had, and using my list from my index cards. Finally, my dissertation advisor said, “Why don’t you just focus on the women who were professional writers?” That was a small enough number to study, although it was still really too many. There were nineteen writers, and some of them had written more than one autobiography. But it got me started, and I managed.

MM: Were you involved with feminism at that time?

RN: Those two women’s history classes had raised my consciousness a little bit. Also, feminist criticism, which was just beginning to be written, had raised my consciousness.

MM: Were there consciousness raising [CR] groups where you were, or feminist groups of any sort that you joined?

RN: Not really. I did join NOW [the National Organization for Women] in Knoxville, Tennessee. I was in Knoxville from 1974 to 1977. I went to one NOW meeting. What I recall is that they were all married women who were complaining about their husbands. I found that really boring. I mean, I was getting ready to get married then, you know? I never went to another NOW meeting.

MM: I was in Knoxville then, and we had the first consciousness raising group. But we were all lesbians, and we weren’t allowed in NOW. Although I did have the opportunity to bring out the NOW president, and she decided she wanted to be a lesbian. That was interesting.

Lesbians weren’t allowed at the Women’s Center, either. There were two women who were lesbians, and who were on the staff who ran the Women’s Center. They sneaked us in at night in Knoxville. It’s interesting to me that you were there at the University of Tennessee then, and involved with that particular group. Yes, the women were complaining about their husbands.

What about your marriage, or your relationship with your husband?

RN: I thought it was pretty good until it wasn’t. We were really compatible as to our interests. My consciousness was raised a little, but feminism was not a barrier at all. He cooked and did more housework than I did. That might have been a problem in his mind. Neither of us was politically active at all, other than voting. I think he had burned out on activism in college, whereas I burned out during Watergate and the McGovern presidential candidacy.

In South Carolina, I was around some political people who were canvassing for votes for McGovern. I did that with them; and, of course, I voted for McGovern. I have never voted for a Republican. I just really didn’t have any interest in politics, and I wasn’t aware of the feminist activism at all. Let alone the lesbian feminism.

I didn’t think I wanted to go back to Alabama.

MM: Were you involved with antiracism work?

RN: Only in so far as I took those jobs, you know, with Head Start, and doing things that were an attempt to help. I never went on marches or anything. I didn’t have friends who did that. Maybe if I had friends who wanted to do that, I would have gone along, as I did in later years. It wasn’t where my mind was then.

MM: What did your friends want to do?

RN: Go out and drink beer. [Laughter]

MM: You and your husband were companionable.

RN: In Texas, I was working as a technical editor, which was a good job. It paid well, I learned a lot from it, and I enjoyed the people, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do with my life. I really wanted to be in college teaching, like him. It just wasn’t going to happen there. Every year we were in Texas, we both applied for jobs in other places. We didn’t want to stay in Texas. It was too far from everything that we liked: our families, our old friends. Texas is not the southeast, it’s the southwest. That didn’t appeal to either of us. Even though there were a lot of people we liked there, the climate is awful, and the general culture of Texas is not appealing to me. He got the job offer that provided the way out: the job at the University of Alabama in Huntsville [UAH]. I would have never applied to an Alabama school. I had never even heard of UAH.

MM: Why wouldn’t you have applied to an Alabama school?

RN: I didn’t think I wanted to go back to Alabama. Now, looking back on having lived there for forty years, it’s hard for me to remember how it felt then. You know, way back then was the time of George Wallace and the racist violence of the 1960s. North Alabama is quite different from the rural, central Alabama where I grew up. But even Huntsville, which is a very progressive city, voted for Trump! And these are educated people! There’s a very high degree of education in Huntsville. That’s NOT what I associated with Alabama.

I’ve forgotten all the places that we applied. Anyway, he got a campus interview at UAH, and he was very impressed. They offered him a job. He told them that if they would offer me a job, too, he would take the job offered to him. And that’s what happened.

They had a second position that they were having trouble filling. It was for a composition specialist. Of course, I wasn’t a composition specialist. I was a technical editor. They were hiring my husband to start a ‘business and technical writing” program. He did have a lot of experience from what he learned to do at Texas A&M.

They have a huge technical writing program at Texas A&M. They offered a master’s degree in technical writing at that time. Maybe a PhD program, too. I had taken a couple of graduate classes there: one in technical writing; and one in rhetoric and composition. We both had a lot to offer. There was some resistance to hiring an academic couple, I later learned. Anyway, they treated us both well although I had gotten in kind of through the back door. I did have to go out and do a campus interview for it. They weren’t hiring me sight unseen, and I have a stellar academic record.

MM: What year did you move to Huntsville with him?

RN: 1983.

MM: You both were teaching at the University of Alabama in Huntsville then.

RN: I don’t want to get into the personal stuff that led to the divorce, which happened in the third year that we were here in Huntsville.

MM: Are you still friends?

RN: I guess so. Although I have not seen him in years. I didn’t want the divorce at first, but I think it turned out well for both of us.

MM: Did you feel stuck in Huntsville?

RN: No. I had other job offers; but when he left, I inherited his position: Director of Business and Technical Writing. It was a good job. I had interviewed at other places for other jobs, and I knew this one was a better job than anything else I was finding.

There was one job I thought I really wanted, one that would have let me teach both technical writing and literature. I think I didn’t get it because they wanted someone who was more committed to teaching technical writing. At most places, if you took a job in a technical writing program, that would be all you would ever teach. If he had not found another job first, I would probably have taken one of those job offers anyway. We weren’t enemies or anything like that. After the divorce, it just would have been uncomfortable being there with him in the same department, teaching in the same program.

I taught five classes a year: courses in technical writing, literature, and women’s studies.

MM: How was it for you doing all of that technical writing when it seems to me that you were so much more inclined toward the literary side?

RN: You know, there were interesting things about it. It was way more interesting than teaching freshman English, and the classes were smaller. That was a huge draw because if you taught technical writing, you usually didn’t have to teach freshman English, and you didn’t have the relentless grading of essays every week. In technical writing, the students were advanced in their major, and conceivably were interested in what they were writing since they were writing about a subject in their field of interest. And you could sequence the papers so that they developed a topic over time: proposal, progress report, draft final report, final report. We also had a business writing class that was different from the technical writing class, and those were advanced students, too.

By then, we had made so many compromises just to get jobs, just to keep a foot in the door. It became clear to me that once I got tenure, I could probably teach whatever I wanted as long as I kept the program going. That meant I had to teach at least three business and technical writing classes. I taught five classes a year, three in one semester and two in the next. I also got to teach classes in women writers and African American women writers, and other classes.

MM: How did that happen?

RN: I just proposed the courses. I can’t remember exactly. The first thing I did was to propose a graduate program in technical communication, a graduate certificate program, with five graduate classes. It was very successful. We already offered a master’s in English; but I wasn’t allowed to teach anything in the master’s program, being the technical writing professor. There were no technical writing classes on a graduate level.

The graduate certificate program changed that. Once I was in the graduate faculty, I could teach graduate literature courses, such as Women’s Autobiography, which I taught several times. I taught a Virginia Woolf seminar four or five times. One of those was in England, in a “study abroad” course that I had proposed.

We also had the women studies program, which I cofounded with Nancy Finley from the Sociology Department and Sandra Carpenter from the Psychology Department. It brought together courses from all over the university, especially in liberal arts, and faculty who were teaching things relevant to women’s studies. We created a women’s studies minor at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. My course on women writers was part of that. I also taught the class, “Introduction to Women’s Studies,” when I was director of the Women’s Studies program. `

MM: Was the administration enthusiastic about your proposals, and supportive of them? Or did you have to fight to get them in? Tell us about that.

RN: [Laughter] We had to fight. We had to propose the women’s studies minor three times. We went through three different administrative processes. After each one, we would have to figure out what we would have to do to make it fly.

I especially remember one professor who opposed it: one of the department chairs, who was later a dean, and the psychology department chair. I was elected to go to talk to her about it, because nobody else would do it. I don’t know that I changed her mind, but at least I talked to her about it.

Later, when she was dean, she was great to work with. I was the department chair during the time that she was dean. I had been the director of Women’s Studies before that. She was very good to the Women’s Studies program, even though she had first opposed it when we were trying to get it approved. We never did know why we were successful in getting it approved. One day, we were driving out of town for a Huntsville Feminist Chorus retreat, and somebody told us the Women’s Studies program had been approved! We had thought it was “dead” again. Yet somebody had gotten it approved. I still don’t know what got it through all that resistance.

MM: Tell us about the Huntsville Feminist Chorus and how that overlaps.

RN: They do kind of overlap. I had gotten tenure in 1989. It was after my tenure that I was able to do more. The chorus started in 1993, and the Women Studies program, I believe, was 1996. People disagree about what started the Huntsville Feminist Chorus.

MM: Tell your version.

RN: I’m going to tell the version that I’ve heard, and that I think is probably close. I joined the chorus when it started. I wasn’t part of making it happen. At the time, I thought we might just have an informal get together to sing regularly. Sherry Merceica had bigger ideas.

You know, there’s a good women’s community here in Huntsville. A lot of lesbians everywhere. When I came out, which was in 1990, it was like the scales were lifted from my eyes. I realized that lots of people that I knew were lesbians.

MM: Can you talk about that, about coming out?

RN: There’s not a lot to tell. I will say that it definitely made me way more of a feminist. It really raised my consciousness a lot. If I had joined NOW when I moved to Huntsville, I would have left him instead of him leaving me. Because they were all lesbians. Or if they weren’t to begin with, they became lesbians.

First, I’ll finish telling you about the Huntsville Feminist Chorus. A lesbian couple started it, Sherry Mercieca and Justine Shrider. Sherry was the director, and Justine was the business manager. I think what really started it was when Betty Clemens and some other people organized an event at the Unitarian Universalist Church. People from different nonprofit organizations had display tables. It was not just feminists, but any kind of nonprofit activism.

One of the things that they were looking at was, “What do you think we need that we don’t have now?” Somebody, maybe Sherry, started making a list of people who were interested in having a feminist chorus. At that time in Georgia, there was the Atlanta Feminist Women’s Chorus, and maybe that motivated them. Sherry was a talented musician. She and Justine decided to take it on. They sent the word out. I’m not sure how they got the word out, but everybody knew about it because everybody in the women’s community knew Sherry and Justine.

I think we probably had twenty people in the chorus that first year. We were meeting at the Girl’s Club, and I think we were able to have the space for free. It was in an old building, and it didn’t have a piano. Sherry must have had to haul a keyboard around. Sherry wrote music, arranged music, and found music. She could listen to a song, write it down, and then arrange it for the voices that we had. She was wonderful at that.

Maybe five of us from that first year are still in it. Every year, membership shifts and changes. The group has just resurfaced after the COVID years. We went through a three-year hiatus when there was no place to meet and no place to rehearse. People were rightly concerned about contagion.

Our director, Pam Siegler, was the one who decided this year to get us back together. Pam, a retired choral director and science teacher, is our fourth director, and the one who has been with us the longest. She’s the first, trained choral director that we’ve ever had. Sherry had trained in operatic music, and Angela Lucas, our second director, had trained as a musician, not as a choral director. Our third director, Carol Crosslin, was a band director. Now, we have someone who was actually trained as a choral director. Pam has been with us since 2010, except, of course, for the three-year hiatus during COVID.

MM: There’s a difference in the chorus with each director, as I recall. I never missed a concert for a while there. How did you get into performing at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, what was the reception, and how did the Chorus became so wonderfully loved there?

RN: There was a connection to the Women’s Studies program always. Our first concert was down at Sacred Heart Monastery, a convent in Cullman, Alabama. They had a nun there, Sister Maurus, who ran an annual weekend retreat called Women Spirit Rising. Sherry and Justine were friends of Sister Maurus, and she brought us down to sing for Women Spirit Rising. That was February 12, 1994, our first public performance. Sherry was looking for other places for us to sing.

Our first University of Alabama in Huntsville [UAH] concert was March 9, 1996. That must have been the year that we started the Women’s Studies program because the Women’s Studies Department sponsored that concert in celebration of Women’s History Month. I don’t remember what the program was, but I remember one song was about Lydia Pinkham, who was a business woman who sold a popular tonic. I have a big sign with her picture. Her picture was on every bottle of tonic that she sold. I marched around the stage holding that sign while we sang her song.

MM: Was there a problem getting the venue? Were they wide open to it, along with the Women’s Studies program?

RN: We never had any trouble reserving the space. We just had to find a time when the Music Department wasn’t using the recital hall. If the Huntsville Symphony had a concert that weekend, we could usually get the recital hall because the Music Department tended to be participating in the symphony. Over time, changes made it harder sometimes. When they remodeled the recital hall, it became more in demand.

Recently, Erin Reid, who is Pam’s partner and who works at UAH, has been reestablishing our connection to the UAH Women’s Studies program, which is now called the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program. They are interested in making some kind of a formal connection with our feminist chorus. We could become a non-affiliated organization that has an understanding or agreement with a UAH program. That will give us access to UAH facilities at no charge, which is a big deal.

We’ve just recently been looking for a place to do a Winter Solstice concert, and the recital hall at UAH wasn’t available because is closed for the holidays. Once it’s closed, you can’t use their buildings. There’s this wonderful lodge at Monte Sano State Park that costs $800 for four hours, and you can’t reserve it for less than four hours. We decided to raise the $800 and do it. It’s a real stretch, because we never charge admission to our concerts. We rely on dues from chorus members, which barely covers renting rehearsal space.

I used to get crushes on nuns in the movies.

MM: That’s wonderful. Tell about Sacred Heart, the nuns, the retreats, and your relationship with them.

RN: One way I got to know a lot of women in the Huntsville women’s community was through a therapist I went to, Betty Giardini, who was a good friend of Betty Clemens. Betty Giardini was a straight woman. Betty Clemens had been straight, and she came out as a lesbian, as I did, after a marriage. Betty Clemens was with the same woman partner for about thirty years, I think.

Betty and Betty would organize a “Women’s Getaway Weekend” retreat at Sacred Heart. The facility is just a building on their grounds that has bedrooms, a living room, and a kitchen that you can book for the weekend for a reasonable price. The building can accommodate about twenty people. We went down there for the weekends every now and then. It was not a structured weekend. We brought things that we wanted to do individually. I might bring my Tarot cards. Someone else might bring grapevines to teach us how to make a grapevine wreath. Or story-telling. It was just a lot of fun.

I got to know all these women that I wouldn’t have known, both straight and gay. They were mostly friends or clients of the Bettys. I remember one time we all made quilt squares for a quilt celebrating Betty Giardini’s sixtieth birthday.

MM: What were your personal feelings toward the nuns?

RN: Oh! That nun story that I read at Quarantina! [Fun with Quarantina is a weekly reading group via Zoom, started at the beginning of COVID.] That story was mostly about nuns in the movies. These nuns at Sacred Heart were the first real nuns that I ever met. I used to get crushes on nuns in the movies. The nuns at Sacred Heart are just such unusual nuns. Some of them, especially the really old ones, would wear those Black habits and the head covering and everything. Most of them just dressed normally and did things like massage therapy, the Woman Spirit Rising events, social justice activism, and even auto mechanics. I knew nothing about Catholicism due to my Baptist upbringing.

MM: You liked the nuns.

RN: Yes, I liked them. I don’t know. I can write about this easier than I can talk about it. I think I romanticized nuns, the way some people do. But what’s attractive is women living without men. I didn’t recognize that for a long time.

MM: Yes, it’s a beautiful story. Tell about your coming out. How did you come out?

RN: I went to an academic conference about autobiography, the first of what became an annual autobiography conference. That first year, it was in Portland, Maine. It was also on the weekend of my fortieth birthday. I didn’t know anybody there, personally, although I was on the editorial board of an autobiography journal, and I knew some of them by name through that work. There was a meet-and-greet mixer at the hotel. I was standing there looking for somebody to talk to. I went over to a woman who looked friendly enough, and I said hello. It turned out she’d had her eye on me all weekend.

MM: Life begins at forty.

RN: It surely did for me! She courted me for two more conferences. We went to the Modern Language Association Conference, which was in New York City that year, and she lived in Philadelphia [Pennsylvania]. We shared a room, totally platonic. Because I was straight, you know? I knew that she was gay, lesbian—I knew this. But I thought that we were just friends. Then, we went to a conference on narrative technique in New Orleans [Louisiana], and that was when she “put the moves” on me. It was her Easter holiday, and I had driven to New Orleans while she had flown there. The plan was for her to ride back with me, to stay with me in Huntsville, and then, to fly back to her home from Huntsville. That was when I got the picture. We dated for a year or so, flying back and forth to see each other.

MM: Was your husband…?

RN: We had divorced in 1986, and this would have been the fall of 1989.

MM: What did you think about all that?

RN: It was a revelation. It was a total revelation! I was very, very unhappy at that time. That’s why I was seeing a therapist. I was so unhappy. My best friend Jane, an art historian, had moved away that year, having gotten a job near New York City. I didn’t have any good friends nearby. Just remembering it makes me a little sad even to think about it. I can remember crying while driving to school just because I felt so depressed about everything.

MM: Lonely?

RN: Yes.

MM: How long did you see this woman off and on, your conference lover?

RN: About a year. She would fly into Nashville [Tennessee], and I would meet her plane there. We would stay there and go to the Grand Old Opry. Or I would fly somewhere else. We took trips to Boston [Massachusetts] and the Outer Banks off the east coast of North Carolina. I think it went on for about a year before I met somebody else, somebody in Huntsville that I fell in love with. I wasn’t seriously in love with the first woman. I was in thrall, in a way, I guess, because it was new and exciting, and because and I love to travel, and the affair lent itself to travel.

Feminist is not equal to lesbian. Lesbian is not equal to feminist, either.

MM: The woman you fell in love with: was she local, or did you travel again?

RN: Local, yes. At the university. That would be our friend Nancy.

MM: That would be Nancy. I hear Nancy coming back and saying, “There’s this new woman at the university and I think she might be…” Later, she said, “She IS!” That’s when she brought you around, and there you were.

RN: Yes, I’ve learned a lot more about feminism and feminist activism since coming out as a lesbian than at any time before that. Even though I read a lot of feminist criticism and I wrote a lot of scholarly papers from a feminist point of view, I had no idea that so many feminist scholars that I was reading were lesbians. I mean, it just didn’t occur to me. Joanne Braxton wrote Black Women’s Autobiography, a book I really liked a lot. Years later, I found out this woman was a lifetime lesbian. I had no clue. It just didn’t cross my mind.

MM: What did you learn when you came that was different out about feminism?

RN: That’s hard to say. I guess it had to do with the politics of feminism and activism. I don’t really know. I think I thought of myself as a feminist. I thought, “We don’t have to be a lesbian to be a feminist,” which you don’t. I remember teaching that. Feminist is not equal to lesbian. Lesbian is not equal to feminist, either.

MM: Yes, it doesn’t work like that. It does overlap a lot among our lesbian friends.

RN: This work we’ve done on the Southern Lesbian Feminist Activist Herstory Project has made me realize just how many of the leaders in the feminist movement were lesbian, not necessarily when they started, but very soon after. So many of the changes and important things that were accomplished were accomplished by lesbians. Lesbians were and are more committed to overturning patriarchy. The straight women always kind of had a foot in the other camp.