Miami Dyke Stories

When I came out in the 1950s in the greater Miami area, there was no such thing as “political activism” around being a lesbian back then, because in those days being gay was a criminal offense and often was prosecuted as such. Our activism consisted of simply existing, of being who we were in a hostile world. By the 1960s, many of us also became involved in the civil rights movement around integration (although not as out lesbians), and in this way we learned the fundamentals of political activism.

In 1956, the infamous Johns Committee Investigations began. State Senator Charlie Johns, a Joe McCarthy worshiper and emulator, embarked on a ten-year-long reign of terror over the lesbians and gay men living in Florida, especially university professors and schoolteachers (Merril Mushroom – Older Queer Voices: The Intimacy of Survival). Using paid informants, illegal wiretapping, and entrapment, investigators built up lengthy files on the private lives of suspected homosexuals. During secret hearings, these victims were interrogated, intimidated, threatened, and finally dismissed from their jobs and publicly humiliated. Many, having lost their livelihood, their families, and their standing in the community, took their own lives.

But even so, back in the day, gay life was tres gay, and we all were gay, not lesbian – that word was used only by clinicians – gay guys, gay girls, gay bars, gay beach, gay parties, gay culture, entertainment, and the arts. I know now how fortunate I was to have come out immersed in such a rich culture, despite all the danger and vilification. Even though we could be (and often were) arrested, incarcerated, fired from our jobs, thrown out of our families, and publicly disgraced, we had the strength of our numbers and the support of others in our large – and fun — gay society.

By the end of the 1960s, there had been a gay uprising at the Stonewall in New York City, “homosexuality” was no longer defined as a mental illness, sodomy laws in many states were relaxed or even repealed, and closet doors started creaking open. In 1974 in Miami, Mary Sims met with Louise Griffin and Maryanne Powers and six other women to start a Lesbian Task Force of the Miami National Organization for Women (NOW). They did workshops for the public promoting positive images of lesbians. They stamped “lesbian money” on the money they spent (these were the days when mainly cash was used, not credit cards). The membership of the Task Force grew to almost 200 women.

“A day without human rights is like a day without sunshine.”

In 1977, the city of Miami passed an ordinance banning discrimination based on sexual orientation. Lesbians and gay men no longer were arrested, prosecuted, and incarcerated, because being who we were no longer was a crime, and our strength grew. So it was not surprising when Anita Bryant, in hysterical fear of us, formed her “Save Our Children” campaign and had the Miami ordinance repealed shortly after it was passed, in order to save children from the “homosexual menace” – just like what had been happening back in the Charlie Johns days.[1]

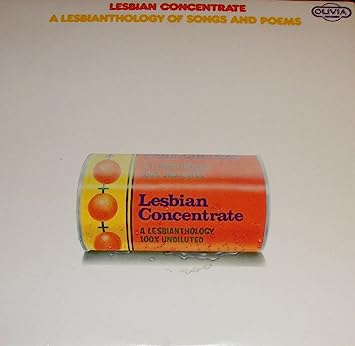

But this time, there was a difference. Anita Bryant, a beauty pageant winner and pop music star whose hit recordings included “Till There Was You,” “Paper Roses,” and “Little Things Mean a Lot,” decided to take her campaign nationwide to prevent enactment of legal protections for lesbians and gay men in all the states. This energized lesbian and gay activism across the nation, and this activism began in Florida. Lesbians and gays organized a nationwide boycott of orange juice because Anita was the national spokeswoman for the Florida Citrus Commission (FCC). The lesbian/gay Miami Victory Campaign pirated the FCC slogan “A day without orange juice is like a day without sunshine” and printed up t-shirts that read “A day without human rights is like a day without sunshine.” Bartenders nationwide stopped making screwdrivers with vodka and orange juice and, instead, made the Anita Bryant with vodka and apple juice. Lesbian musicians and other performers joined the party, writing songs for Anita and releasing songs like those on Olivia Records’ album Lesbian Concentrate.”

The boycott lasted until 1980, and Anita Bryant lost both her spokeswoman job and her celebrity status. But lesbian mothers still were losing custody of their children, and gay people still were facing discrimination in employment and housing. It took until 1998 to gain our legal protections in Florida, and these can be (and are being) chipped away at again, until they will be quite gone again.

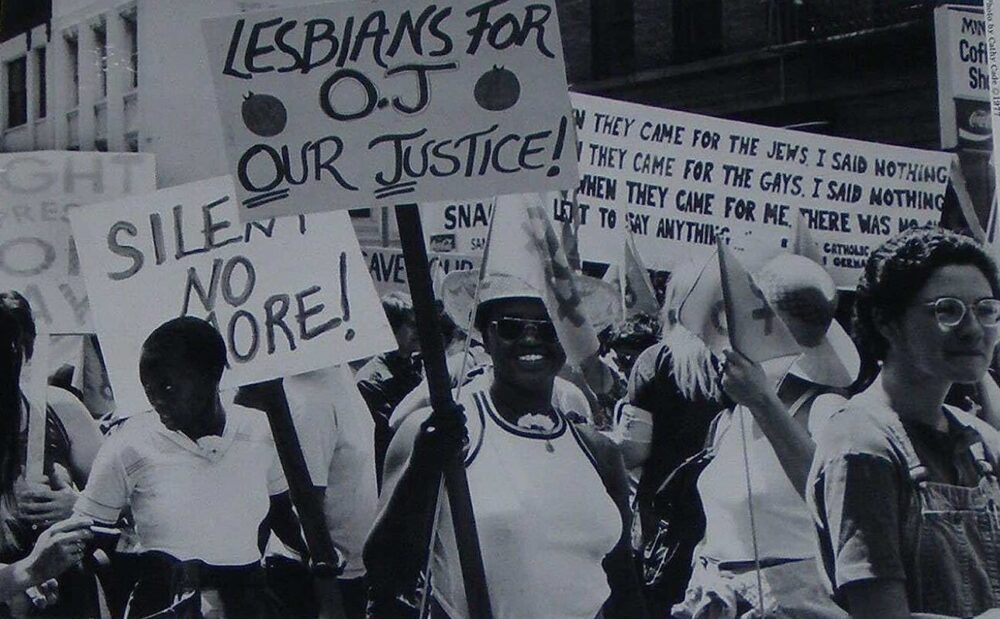

With the demise of the Johns Investigations, the humiliation of Anita Bryant, and the uprising at the Stonewall bar in New York City, we began to learn that we could engage in political activism with a little more safety. We could be effective. We lesbians took back our noun, reclaimed our dykeness. The rise of the swelling tide of feminism provided us with structure for our activism. Some of us became separatists. We developed an increasing awareness of sexism, racism, and tools that the heteropatriarchy used to keep us separated and subservient. We became aware of the unfilled needs of our sisters, and there was no logic to our lives after knowing this except that we must work together united in our purpose to take care of one another. And so, the radical lesbian feminist activists in Florida – as they were doing throughout the nation – began to move, to organize, to do the work that would create a better, gentler world.

The diversity and range of Miami lesbian activism in the closing decades of the twentieth century shine forth in interviews with Miami dykes Mindy Dyke and Mary Sims as well as stories of Miami activism by Maryanne Powers, Amani Ayers, Lu Rivers, Charlotte Brewer, Martha Ingalls, and Barbara Ester (“A Trail of Dykes” and “Roots and Branches“). Let their stories enhance our energy in these days to come, as Florida dykes, along with some of us in other states, face yet another barrage of oppression by the heteropatriarchal legislators that currently hold power in the state.

[1] See chapter 21 of Rebels, Rubyfruits, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South by James T. Sears (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001) for the story of the referendum and the gay activism stimulated by Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign.

Interviews with several Miami dykes politically active in the 1970s and 1980s are published in our special editions of Sinister Wisdom (see Sinister Wisdom volumes 93, 104, and 109). We have made these stories available on this website, along with full interviews with some of the women.