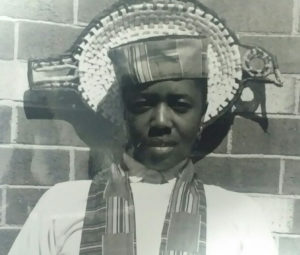

Jaye Vaughn, Founder of Cedar Chest, an Organization for Lesbians of African Descent

Jaye Vaughn started Cedar Chest for lesbians of African descent in 1994; and later, the Center for Non-White Lesbians, in Durham, North Carolina.

Edited for the web by Merril Mushroom from notes from a phone interview by Rose Norman on December 18, 2015.

Jaye Vaughn: My name is Janice “Jaye” Vaughn. I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, the oldest of four children. I had one brother. I had a very pleasant life growing up with extended family who helped raise me. My mom had me when she was only 18 years old; and so, my grandmother and grandfather had a lot of influence on me. While my mother was in college, I lived with my grandparents during the week. I would be with my mother on weekends. My grandmother died when I was 12, and I stayed with my mother from then on.

I attended segregated schools from kindergarten through first grade. They had a program where young Black children could start early. I started kindergarten at age four. After fourth grade, Charlotte started busing kids from the inner city to the suburbs. My family actually already lived in the suburbs. We called it the country. After sixth grade, my high schools were more racially balanced, about fifty-fifty. We were bused to make that balance. I went to six different schools from kindergarten through twelfth grade. I had to learn to adjust quickly, to make friends, etc.

My family was determined to keep me in the best schools. For example, if we lived in a certain area where that school wasn’t the greatest, my family would write a note that they would drive me to another school. Because I lived in the “country,” out in the suburbs, I wasn’t riding a bus there. My family was driving me over to another school if that was a better school.

Biographical note

Janice “Jaye” Vaughn (born 1959) grew up in a middle-class family in Charlotte, North Carolina, the oldest of four children. Entering fifth grade, she was one of seven Black children who integrated a Charlotte elementary school. She attended fully integrated schools in Charlotte throughout high school. She graduated from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in 1981 with a degree in radio, television, and film.

The inner-city kids were riding the bus out to the suburbs, and I was driving to wherever the best school was, no matter which side of town it was. I went to East Mecklenburg High School from grades ten through twelve.

Charlotte was the first city in North Carolina to integrate. When they integrated, I was in the fifth grade. I was one of seven kids sent to Albemarle Road Elementary, an all-white elementary school. Before that, I was at Hickory Grove Elementary, second through fourth grade, which was an integrated suburban school with Black kids in the minority. That was nothing like the experience in fifth grade at Albemarle Road, which was a “model school,” set up specifically for integration, and to see how the Black kids succeeded.

There were just seven of us Blacks in the whole school, two girls and five boys. We survived, and we were told that we had to show people our academic knowledge, what we could do in academia, in order for the race to be accepted, and for integration to be accepted.

I was dealing with two things at that time: being a young Black girl who wanted women’s rights and things for girls to happen, things to be equal for girls; at the same time, I also had to think about my race. I was battling both of those things. I made it through my advanced classes, and I did very well. I spent one year at that school. Then, they bused me to another school.

Charlotte as a city was into busing, and my family was into making sure that I went to the best schools. I did go to schools with great academic history and better supplies for the children. I had a lot of educators in my family. I got a great education and at the same time felt like I was making some progress for women, and for Black women, especially in terms of showing that we could be at the head of the class.

JV: I endured a lot of testing, a lot of pressure having to “make the grade,” feeling I was responsible for my whole race, and for me as a girl child.

JV: In high school, I was involved in all sports from junior high up. I played softball for different churches. In junior high, I was often the only Black on the teams at white churches. I played on the volleyball team and basketball team; and I did track. I was the first Black female at my high school to make the tennis team. I don’t think they’ve had one since. That was at East Mecklenburg High School in Charlotte, which was known for great tennis players. For me to make that team was a great honor. Quite a few of those girls were my friends. I learned to play tennis hitting a ball against the wall of my brick home, and then spending a summer playing tennis at different people’s apartment complexes that had tennis courts. A couple of my white friends would take me to country clubs to play tennis. That summer, my goal was to make the tennis team, and I did. I believe that was 1975, and I was on that team for two years.

JV: My interest in feminism has always been there. I remember wanting to wear jeans when I was between the ages of five and seven. People didn’t wear jeans then. That’s just not what little girls did. But my grandfather let me wear a little cowgirl hat and holster. I was allowed to run around outside with my shirt off until I matured, until I got ready to go to school. I felt the freedom that a lot of young girls didn’t have. It seemed right to me that I should have those freedoms.

Wearing pants and going without shirts when I was young was okay in my family. The feminism came in when I got to school, when I realized that there was a different set of rules for boys than for girls. The people with the pants had all the power (which would have been the boys). I knew that I equally as smart if not smarter than they were. I was in advanced classes all the way through high school.

There was a lot that we girls could show boys – we could compete with boys. So, my attitude started when I was young. I played with a lot of boys when I was young. There might have been two girls on our street, and the rest were boys. For me, the competition in sports was there. I was an athlete all the way through high school. That helped me to learn to be a team player, and to learn the things that boys were taught that we girls weren’t taught. We girls were taught to fuss and fight and compete with each other. Being on girls’ sports teams enhanced my feminism because we were working as a team. We were getting things done together as girls.

JV: I did not come out as a lesbian until I was 25. It would not have been the right thing to do unless you were going to get hit or denied privileges. However, when you were on women’s athletic teams, your peers would often just assume you were gay. I was still wearing pants a lot, and I still wore dresses at the appropriate time. I wore my pants when I didn’t have to wear a dress. In high school, your appearance is everything. What you look like is everything to you.

When I was in high school and junior high, we girls could hug and kiss on each other without anything being said. There were a few of us who knew that meant something different for us than for the straight girls, hugging and kissing when we would win a game or whatever happened. I still had my long hair and perm in high school, but I cut all my hair off, bald, when I was a sophomore in college.

There was no way to come out as a Black lesbian in the 1970s. From 1974 to 1977, I was in high school, and from 1977 to 1981 was college. I did not come out until after college.

I went to University of North Carolina [UNC] at Chapel Hill, majoring in radio, television, and film. In college, I had a friend who happened to be one of the student coordinators for the gay and lesbian organization on the campus. I guess she had been observing me. She invited me to a potluck, a picnic out in a park. I noticed that they were paired off as male couples and female couples. I asked why she brought me there, and she said, “I thought you would like it.” I wondered if it was really showing like that or obvious [that I might be gay]. But I never said I was a lesbian or gay, or that I had any of those feelings.

I was in organizations with women who were out and gay. At that time, 1977 to 1981, I don’t know of any Black lesbians on the UNC campus. I did know of some white lesbians on that campus. I joined She magazine, a feminist magazine on UNC’s campus. That’s where I was able to connect with older girls or girls who were already out. Of course, I could say, “I’m in journalism. I want to write.” I wrote for She magazine for two years. It no longer exists, but it was the first, feminist magazine on the UNC campus.

JV: No, not as a formal group. When I was in college, through straight Black women friends, I had encountered the gay and lesbian organization on UNC’s campus. My major was radio, television, film. In that industry, it was not uncommon to run into feminists, or gays and lesbians. So that was a comfortable specialty for me to go into.

I got into UNC as an accounting major, but I changed it in first semester. I thought that accounting was too boring. When I graduated, I came back to Charlotte, and I worked in broadcasting as a salesperson. I recognized that discrimination and harassment were there. I recall being harassed by a client, going back and telling my boss; and then, not being sent to that client any more, but not knowing where to go.

It was still the “old boy’s network.” If you were a woman, there was no defense. There was nothing you could say. You could lose your job. That’s part of the reason I wanted to see things happen and grow. When Anita Hill stood up for herself [during the Clarence Thomas Supreme Court confirmation hearings in 1991], I knew that I could stand up. Before that, I felt I couldn’t do it. I felt that I couldn’t find any Black, lesbian role models in North Carolina.

I had wanted to learn broadcasting in North Carolina, but it wasn’t available to me then. I left North Carolina in 1981, left my boyfriend, and went to New York City. I went to the Center for Media Arts in New York to learn to be a broadcast technician. I learned about the mechanical aspects: the machines, the electronics, the engineering part of broadcasting. I knew that in New York, I was going to see some lesbians, and I knew I was going to be able to find out what was going on with me. I got there, got in school, and lived in the coed YMCA. I met a group of friends there, all going to school. Two of us were going to the same school, one in audio engineering, and I was in broadcast engineering.

I came out as a lesbian by taking the subway from midtown Manhattan, where I lived, to Columbia University [in upper Manhatten]. I had seen in the paper where they were having a gay/lesbian dance. I caught the subway by myself to go to Columbia that night.

At this time, I’d shaved my hair off bald. I’d first done that in college in 1979. That was a big deal then. If you were a Black woman, you just did not shave your hair off bald. That was a no-no in North Carolina. I was starting to come into myself even that early. It was also a feminist thing, saying to the world that I could wear it like this if I want to. In New York, I snuck over to Columbia University, went to the dance, stood at the wall, and didn’t talk to anybody. I stayed about an hour and a half just looking, and thought, “Wow, this is great!” When I got back, my friends asked where I’d been. One of them guessed where I’d been. They said they’d been waiting on me to come out all that time.

My coming out process was through a mixed-age group of seven or eight. One guy was 60, and the rest of us were in our 20s. We came from different countries, like Sweden, Germany, France. That whole group knew that I was gay, but they hadn’t said anything. So that was my coming out.

I decided to be celibate for a year, which I did. In New York, you could take the HIV test (North Carolina didn’t even talk about HIV). I had been with men, so I decided to take the HIV test, and to stay away from any sexual encounters for a year. I remember reading Peter Pan, and all kinds of books about relationships. I was getting my thoughts together about who I was going to be.

In the process, I met some older Black lesbians when I started going to the clubs. One of them was Jewelle Gomez, and I didn’t even know who she was. So, here I am hanging out with Jewelle Gomez and her friends, and didn’t know who she was. We knew nothing of that in North Carolina. They called me “home grown” in New York because I was from the South, and I was standing around with my mouth wide open all the time.

My question was whether this was a phase, or could I go ahead and have a life as an adult, grow up, have a home, and a job, and regular things that I was used to seeing people have. Can I have that? And they said, “Oh, yeah!” I met all kinds of people there. I could hold hands with my girlfriend and walk down the street. A whole other world opened up for me while I was there.

JV: I was using my electronics abilities, and I had found that up there in New York. I could get a job as an electrical engineer, working on the trains, and make really good money. I was going stay there and to do that. But my mom got sick, and I decided to come home. But… I came home with a girlfriend who had two kids, and she was white. I was coming home with a lot of stuff that I didn’t leave with when I left there.

When I was in New York, I lived in Manhattan most of the time. I moved out to Far Rockaway for a month before I got into the coed YMCA. The last guy I dated was there. He walked into the club, and he saw me go into the lesbian bar. He still wanted to date me. I had to tell him, “We cannot date. It is over. I have decided who I am. I know who I am now.” He was nice about it.

My whole coming out process as a Southerner was in the North, in New York City. That’s where I learned about the writers, Stonewall, the politics. I remembered people in the South calling women “Bull Daggers.” When I went up North, I found out what that was. I grew so much up there. The pain had gone away from feeling I was not worthy, or not right, not human. I had found all those people up there who were gay, and yet, who were all right. I realized I was not the odd ugly duckling. When I came back to North Carolina, I had an idea in my mind that there had to be some lesbians here who were Black. I was going to find them and start an organization. If I reached out, people would come out of the closet. Somebody has to say that we can meet collectively.

JV: When I came back with my little family, in that interracial relationship with two young kids, we spent a lot of time with other couples who had kids or who had adopted kids. I was mostly seeing white people. The only Blacks I recall were Mandy Carter and Wanda Floyd, the MCC minister. We would all end up in the same area. We all went to the same events, but you could count us on one hand. Mandy was very much into the politics. I and my family had always been involved with politics, so I paid attention to what she was doing. I listened and learned.

I had met a group of professionals who were Black gays and lesbians, and who had an organization called Umoja. They would meet “underground,” literally underneath a restaurant that had a back-alley entrance to enter a little room. They would meet there, play music, dance, and have a good time. But there were only a few of them. Meeting Black professionals in the South who had an organization for gays and lesbians was like, “Whoa! Wow!” Those people weren’t necessarily out [about being gay] at their jobs. But they met to have a good time, kind of like in New York. When they decided that either it was taking up too much of their time or they had other things they wanted to do, I started thinking of having a women’s organization.

I decided to start Cedar Chest in 1994. I think I had been back here in Durham maybe a year then. I wanted an organization for women of African descent. Umoja was mostly guys, men of African descent. What I said in my first flyer was this [reading from it]:

“When I was young, the cedar chest at the foot of grandma’s bed was a hope chest for the next young woman in our family to get married. The cedar chest was full of handmade valuables and store-bought gifts given to the woman by family and friends. I am ready, as I hope you, are to establish in our small community a cedar chest of hope for lesbians of color. This chest is full of energy, love, hope, charity, trust, and confidentiality. This is not an outing process or a political club. This is a place to share and support one another. The activities we do will be done at group meetings for us, be it literature, job networking, or any topic we need to share. To become a Cedar Chest Club member, all we ask if that everything be kept confidential.”

I signed it Janice Vaughn, January 1994. I had some business cards made up that I would hand out to anybody that I got gaydar on, any female of African descent. Word got out slowly. We met at my home in Durham. My partner excused herself and her kids. It started out with four or five people, and it just grew and grew because the word got out that this was a safe space.

Sankofa, yes, I used Sankofa at the beginning of Cedar Chest because it means “to go back and fetch it.” When you have moved on and have gotten to a better place, you go back to your family or your roots, and fetch them to the better place. That’s Sankofa. I first encountered that word when I was in college, and then it came back again when I was in New York, at a museum or something. It just stuck with me. At UNC, I took a class in African Art where the Sankofa bird was mentioned in those art books. I just happened to remember it. I had purchased the Sankofa bird symbol from some African people that did crafts here in Durham. We used that as a logo until we got another one, the sticker with the black background and pink triangle in the middle like that the Jewish people had to wear [in German concentration camps in the 1930s and 1940s]. We added to it a strip of green, yellow, red, and black Kente cloth from Kenya. We ended up using those two symbols together.

[Reading again] “Our Mission: The Cedar Chest Club is a club for women of African descent who love women. We meet once a month. Our hope is to be a resource and support group for African American lesbians.”At that time, down here in North Carolina, using the L-word was big. I wanted people to be able to say who they were. If I never said it [lesbian], they would never say it. We had at least 45-50 members at one time. Parties might draw well over 200-300 people. People were coming from Virginia, Georgia, South Carolina, New York, and Washington, D.C. There wasn’t an organization like this that was doing things, saying “Here we are.” People were coming from everywhere. (I remember one woman drove from Virginia once a month for the meeting.) They needed that contact with each other, and to be able to vent and talk and network.

Cedar Chest Club met at my home the first year, and then we rotated among members’ houses. That was a way people could get to know each other. Our first community service project was to identify a family that needed something for Christmas. We took two young girls on a shopping spree. That was a lot of fun. We started doing community service, meeting with a group called Black Men United, a local African American gay group. We met with them and Mandy Carter to discuss strategies to defeat Jesse Helms.[1]

One of the things I would do was find films. I found a book called Third World Newsreel, which had videos and movies you could order. It’s always hard to find a Black lesbian movie. I would start with the women’s section, and find some feminist movies, and then order some Black lesbian movies. There was one about Black lesbians dealing with Christianity; one about living in the ‘hood; one about sexual politics and homophobia. I was paying for all these myself. I would order these videos. We would watch them and discuss them. And then I would send them back. That was how we let people know what was going on around the world and in the United States. These people thought that they were the only ones until they got with another, and another, and another. That’s how they came to discover that there were a bunch of us.

Cedar Chest also brought in speakers. I brought in Pamela Sneed, writer and poet, and she was not well known.[2] After people saw her, she ended up being invited back to Duke for their gay and lesbian writers’ week; and from there she was able to go to Europe. It kind of freed some people. Here’s somebody that was out, and who was talking. She is now a professor somewhere.

Marjorie Hill came to speak to the group. She was a Black lesbian political activist in [the early 1990s, New York City Mayor] Dinkins’s cabinet. They got a whole lot of gay and lesbian stuff passed in New York. People don’t give Dinkins credit for being a Black mayor who did things for the gay and lesbian community; but he did, and it was because she was in his cabinet. You hear them talk about Mayor Koch, but you don’t hear them talk about Mayor Dinkins.

Cedar Chest also went to the Black Lesbian Gay Pride weekend every Memorial Day weekend in Washington, D.C. That was the only Black Lesbian and Gay Pride then. Now we have the International Federation of Black Prides. Back then, 1994 to ‘98, D.C. was the only one. Cedar Chest was well represented there. We had fun, went to workshops.

Part of what I wanted the Cedar Chest Club to do was to take people from North Carolina to New York and other places. I’m very much into education, coming from a family of educators. Every moment I could take to educate people, it was about knowing and learning your roots.

The Cedar Chest Club went from 1994 through 1998. I decided to go to Hawaii with a partner. While I was gone, they couldn’t keep it going. I tried to regenerate it when I came back. I had made a lot of spiritual connections and decisions about myself. I worked at Whole Foods in Durham, where you were accepted as a Black lesbian.

I had gotten out of broadcasting, and I decided to go back to school in nursing. At age 38, I needed to know how I was going to retire. I had taken all that time to discover me, to help people discover themselves, to be a part of the community. Now it was time for me to go back to school. I had reached my limit at Whole Foods unless I wanted to leave the state. I had started out cutting sandwiches, and I was a buyer by that time. I wanted to stay in North Carolina. When I went back to school in nursing, I left the area. I went to East Carolina University, in Greenville, North Carolina. I had to just let Cedar Chest go. They could not keep it together. I think the difference was that it was my baby, and I had the passion. It wasn’t the same when others tried to lead that group.

JV: What seemed to be happening was that as people heard about the Cedar Chest Club, Mexican or Asian or Hispanic people wanted to come. But what we were talking about wasn’t really reaching them. That’s why I started the Center for Non-White Lesbians, and I used the grant money from a lesbian organization called Astraea [http://www.astraeafoundation.org/].

I knew a lot of those guys through people I had met in New York. We started meeting and doing projects. Women from Cedar Chest Club would come to that also. But it was mostly Latinas and Asians, or just people from other countries and cultures who were brown people, or people of color. People who wanted to meet and talk about their perspective in their culture, about what was happening to Latinas, about what was happening to other groups, about what was happening in South Africa.

College students from other countries who were considered minorities showed up at those meetings, too. I stayed connected with the college campuses. Some of them didn’t have organizations at all. UNC always had a gay and lesbian organization on campus, and that was always my starting point. Then Duke got one. When I did the Center for Non-White Lesbians, I put the word out to those groups on campus. It was kind of neat talking about the perspective of the Latina population. I think that it was rougher on them than it was on us, homosexuality being such a taboo in their culture.

The Center for Non-White Lesbians lasted from 1996 to 1998. The Cedar Chest Club lasted from 1994 to 1998. I dissolved both groups at the same time.

JV: I would say that’s true; and that’s why we had such a hard time coming out. A lot of it has to do with religion. Also, you don’t want to lose your job. That’s one of the things we would talk about in our meetings.

[1] Jesse Helms was a homophobic and racist Republican U.S. Senator from North Carolina, running for re-election. He served five terms and was never defeated. In 1990, Mandy Carter was campaign manager for PAC, NC Senate Vote ’90, that promoted former Charlotte Mayor Harvey Gantt’s candidacy to attempt to defeat Helms.

[2] Pamela Sneed now teaches at Sarah Lawrence College, http://www.pamelasneedspeaks.com/

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.