Southern Sisters, Inc.: Women in Print, a Feminist Outpost

Dorothy “Cookie” Teer and Melody Ivins, at Cookie Teer’s home in Durham, North Carolina, interview by Rose Norman, Saturday July 11, 2015. Updated February 2024.

Additional notes from Melody Ivins at Roots Bakery, Bistro and Bar, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, interview by Rose Norman, July 14, 2015.

Dorothy “Cookie” Teer and Melody Ivins, Southern Sisters, Inc.

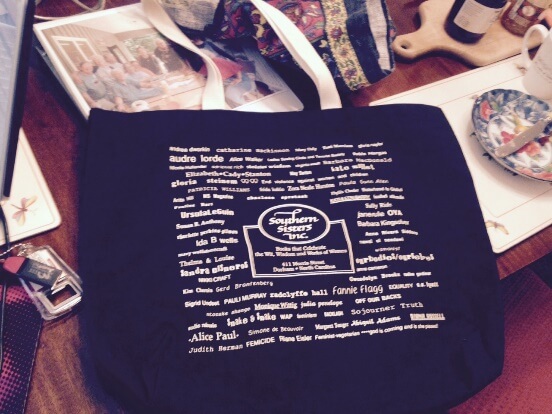

Southern Sisters was a feminist bookstore in Durham, North Carolina, in operation from 1988 to 1995. It was the brainchild of Dorothy “Cookie” Teer and her friend Jane Ryan. Cookie recruited two more of her friends, Bibba Montgomery and Melinda Vise, to help them start the store. Melody Ivins managed the store for most of its history because she had experience with bookstores that Cookie and her friends lacked. At the time of these interviews, Southern Sisters was the only feminist bookstore we had identified in North Carolina.

Note: Since this interview, we have identified two other feminist bookstores that operated in North Carolina, both of which were located in Charlotte. Rising Moon, owned by Sue Henry, was primarily a GLBT store and community gathering place. The Bag Lady, started by Hope Swann as a jewelry, gift, and book shop, is still in operation as of 2024, https://the-bag-lady.biz/.

Sue Henry of Rising Moon is a lesbian, and Hope Swann of The Bag Lady is not.

Malaprop’s Bookstore in Asheville, North Carolina, was on the Feminist Bookstore Network’s core mailing list, but does not identify as a feminist bookstore. Feminist Bookstore News described Malaprop’s Bookstore as an “alternative” bookstore. It was never intended to be an exclusively feminist bookstore although its original owner and 1982 founder, Emöke B’Racz, is a lesbian. Malaprop’s Bookstore website says that, “We bring books, writers, and readers together in an environment that nurtures community and the joy of reading“ (www.malaprops.com).

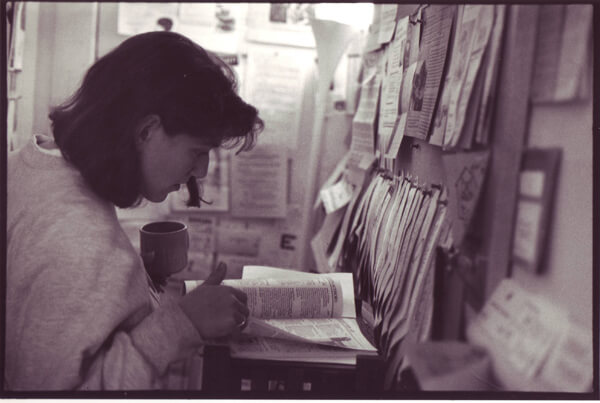

Melody Ivins

My parents were military, and I grew up mostly on military bases in the South. Living on base is very different from living off-base, as I discovered when my father retired. When I was age ten to thirteen, my family lived in Naples, Italy, which was heavenly. When my dad retired, we moved to Smithfield, North Carolina, which still had its gigantic Ku Klux Klan sign up welcoming [white] people to town. It was 1968, and I was 13. We had no idea of the community where we were moving. The schools had just integrated, causing a lot of tension that nobody was talking about. We were weird, “Eye-talian” [Italian] Yankees. Yes, it was rough.

I was a feminist from the minute I heard the word.

I went to school at University of North Carolina, in Chapel Hill. I pretty much took one look at Chapel Hill, which is the liberal bastion of North Carolina, and thought. “This is the place for me.” I studied English at UNC, and I won highest honors in poetry writing. I’m one of the people who did school here and never left because I love it here. I did move to Durham to manage Southern Sisters, living there for thirteen years. Eventually, I moved back to Chapel Hill, which, for a non-driver, is much easier to negotiate.

I’ve had a whole career in restaurants, another whole career in librarianship and bookselling. I currently do historical research, specializing in Southern, African American, and women’s history.

I was a feminist from the minute I heard the word. They called it “women’s lib” then. Kate Millet appeared on the cover of Time Magazine. She looked angry, and she was smart, and she had a book called Sexual Politics. I was 15 years old, and I knew I’d been waiting for that. That was it.

When I graduated from college in 1980, it was beginning to dawn on me that I had had only one woman professor in the English Department, and we studied only one woman writer in any depth at all. And UNC Chapel Hill had an excellent English program. In the poetry sequence (and I took every poetry class that I could), women poets were presented differently from the male poets. I wrote a paper about this. Walt Whitman is this giant striding the centuries, and Emily Dickinson is this little.. ghost. They’re both founders of modern American poetry.

Cookie Teer

I’m from Durham, North Carolina. You asked if I identified as Southern. No. Never have, never will. My family was split. My mother was a Yankee. Yes, of course, I grew up in the South. It was a very privileged, enclosed position. I grew to be aware of everything around me. Without knowing it, I was watching my mother and her difficult life, and it was my precursor to feminism, especially when the light bulb went off.

I call it “the era of the 400 phone calls.”

You’d call somebody who told you to talk to somebody else, and so on.

I came to feminism through a very peculiar route. I was older than the average person who gets the calling, which is good because I had the energy. I came to it through the antipornography feminist movement. Andrea Dworkin was one of my mentors and a very good friend. I had a lot of good friends like that. An outgrowth of that was working with women in systems of prostitution. We did a billion slide shows. This was a group we formed called Pornography Awareness. Our mentors were people like Women Against Pornography in New York, Dorchen Leidholdt, and people like that.

I call it “the era of the 400 phone calls.” You’d call somebody who told you to talk to somebody else, and so on. I just kept going. That’s how Pornography Awareness came along. We did slide shows for everything from mothers of twins, to presenting for the Girl Scouts, to a Baptist church, and to many law schools. My first antipornography slide show was at UNC Law School. My last antipornography slide show was in 1995 at Duke Law School in North Carolina. We did slide shows everywhere from Princeton, New Jersey, to Texas. It was very fatiguing, very draining. Because of the activism and being out there, people would ask us to serve on boards. It was mostly a band of women doing this tour. Some men did get involved, and they helped out. But it was kind of a women’s thing. This nucleus group of women, most of whom were straight women, with some lesbians, partnered together. We became the antipornography group.

Southern Sisters Beginnings

Cookie Teer: How Southern Sisters got born was by my having dinner one night with my friend Jane Ryan. She was the first of four founding mothers of Southern Sisters, of which I’m the only one still living. Jane was the oldest by a long shot, fifteen or twenty years older than I was. [This would make Jane Ryan born in the 1920s]. Jane led a fascinating life. She came from Charleston, South Carolina, and she married when she was sixteen. She had seven kids, and she left that husband and the kids. Then, she came to North Carolina. She was not a college graduate then. She attended North Carolina Central, and earned two graduate degrees, working in juvenile justice. Jane was a quirky, cranky gal. She identified as lesbian, after she left the second husband, Frank Ryan, a historian at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and they remained friends until she died. I still do Facebook with some of her children.

Jane and I were having dinner in Durham, and I was saying that we should picket the Durham Morning Herald about their coverage of AIDS. I said that we ought to make an appointment with the editor. Jane didn’t think that picketing was the best use of our time, and she said, “How about if we do a bookstore?” That had never crossed my mind, and now, I could see it as an offshoot of all this other stuff. It became focused, crystallized. I went right home and called my best friend, Bibba Montgomery. She and I had met through all this activism. Bibba had been a former head of the local chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW). When I told her about it, she said, “Count me in!” She was the third person involved, including me and Jane..

The fourth person was Melinda Vadas, a philosophy professor at a historically Black college, Winston Salem State University. I had met her through feminism. I put her on two symposiums. One in 1984 at Duke University [Durham, North Carolina], was a way to bring Andrea Dworkin here. We had everybody there from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to you-name-it, states’ attorneys general. A year later, I did one at North Carolina Central University. Byllye Avery was a keynote speaker there. We did another symposium about prostitution, looking at women across race and class. These were big symposiums.

I met Melinda at the first of those two symposiums. Melinda was a big animal rights person, very passionate. She was a silent partner in the bookstore, and she didn’t live here. She came in occasionally.

Now that we had the idea, I decided that we wanted it in Durham. I wanted it to stand alone and to be something beautiful. I never saw myself as part of the “left,” or a hippie, or any of that. We found the building we wanted.

Melody was always surrounded by books. I knew Melody. I had been to her archive of books. I also knew that she managed the Women’s Book Exchange. She knew everything about books. The others of us didn’t know squat about books. If we’d known what it was going to take, we wouldn’t have done it! You had to be passionate and crazy.

None of us had ever started a business like that from the ground up. We didn’t even know how to order a book. I’ll tell you what the first book was that we ordered: seven copies of Jane Caputi’s The Age of Sex Crimes, from Bowling Green Press. And we ordered $700 worth of Mary Engelbreit greeting cards.

Women’s Book Exchange

Melody Ivins: I was working for a library research service right after college. It was owned and operated by Eva Metzger, and she employed her two daughters. International Woman’s Day was coming up, and I wanted to read the speech from “Ain’t I a Woman.” I went to the main library on campus, where I could not find it. This was partly my own ignorance, not knowing where to look. I wasn’t even sure who wrote it, Sojourner Truth or Harriet Tubman. I couldn’t find the speech, and I came back to work, steam coming out of my ears. Eva and her daughters were right with me. “That’s outrageous! We’ve got to do something about this!”

We’d never dreamed of opening a bookstore. We did not have the resources. We had heard of feminist bookstores, and we were all library people. We had more space in the office suite than we actually needed, and Eva donated the use of the front office, office supplies, utilities, and copier. We all went out and started scrounging books by, for, and about women.

We would make the rounds of the local bookstores, and we traded what we didn’t need for books that we did need.

This was the most tremendous fun ever.

We opened in February 1983 with 200 books. None of us had ever seen that many books about women in one place before. Annual membership was $5 to $10, which was big money in those days. By the end of the week, we had fifty members. We were off to a really good start. It was called the Women’s Book Exchange.

People donated books, and we learned quickly what we needed. We would make the rounds of the local bookstores, and we traded what we didn’t need for books that we did need. This was the most tremendous fun ever.

About this time, Spring Brooks (the volunteer who never left) was working with us. For the first three years, we were in Eva’s front office. Eva and her daughters got less interested as time went on. I was running the show with some wonderful volunteers, including Spring. Then Eva wanted her front office back. We ran into the fierce Communist guy, Bob Shelton, who ran International Books, and his sweetheart, Marilyn Ghezzi. They offered us the back room at their store rent-free. Bob thought they needed that space for storage, while Marilyn argued that we would bring in a lot more foot traffic.

We moved into their back room. I hate to think how many times we boxed up and moved those books over the years. The back room of International Books was our best location. The collection grew to 5000 volumes before we left. We sold t-shirts and buttons and postcards. It was a piddling amount of money, yet enough to pay for the tape that we used to mark our books and our basic office supplies. We attended street fairs, where we took a table full of books as a display. Everybody wanted to buy them, and we always explaining that we were a library.

Along the way I had met Kathy Hopwood and Beth Siegler, of what was then Triangle Women’s Martial Arts, and worked with them. I met Candy Hamilton, Mab Segrest, and Mandy Carter through the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. We started developing a network that included the vibrant women’s community in Durham.

Somewhere in there, some of the early visitors to the library asked where the lesbian books were. We discovered there were whole presses publishing lesbian books. The Women in Print movement was just blossoming then. It was really exciting to find those books, to collect them, and to get them to the people who needed them. That’s what I loved. That’s when I met Cookie, doing Women against Pornography. At one of the street fairs, the table assigned to Women’s Book Exchange was in front of a store that sold a lot of pornography. We asked Women Against Pornography to come share our table.

[Melody Ivins asks Cookie Teer] Did we organize together, or was it just the Women’s Book Exchange that picketed the strip club, upstairs on Franklin?

CT: I don’t remember.

MI: This place had put a big ad in the student newspaper, an ad that was really vile. Even men I knew who were not particularly feminist were disgusted. Thus, we organized a picket there.

For me, the books and the activism always went together. It was the determination to have books for all women and sympathetic men; and to have resources for raising kids in a non-sexist way. I was getting a crash course in race, class, orientation, and disability. It just kept expanding. I’m getting goosebumps remembering it all.

By the time we were at Southern Sisters, I had managed Women’s Book Exchange for five years. Spring managed it for a couple of years. We moved it from International Books to the Women’s Center in downtown Chapel Hill [North Carolina]. We were amazed at what we found there because even though we were young and radical, and even though I’m straight, we knew that it was lesbian feminism and separatism that was what was going on then. That was a part of my education. Here we were, young and rowdy, and this was the country-club set running the Women’s Center.

My father was dying the year Southern Sisters opened, and I didn’t have much energy for the Women’s Book Exchange. Someone saw an open copy of The Joy of Lesbian Sex at the library, and it caused everyone to freak out. The old biddies at the Women’s Center wanted us to keep these books under lock and key.

Someone saw an open copy of The Joy of Lesbian Sex at the library, and it caused everyone to freak out.

The old biddies at the Women’s Center wanted us to keep these books under lock and key.

We had a section called “The Body,” which included health, sports, and sexuality. We offered to put the books with graphic depictions of sexuality in a separate section on a high shelf, where little kids and little old ladies would not stumble upon them by accident. That wasn’t good enough for them. They set one of their peers on us, a retired University of North Carolina librarian. Funny, she was absolutely on our side. She told them that what we were doing was right. This was what the American Library Association does. Get over it!

They would not get over it. We set up an appeals process, etc. They just would not get over it. A woman politician took it upon herself to find other things besides the lesbian materials to complain about. This was in order not to look so pointedly homophobic. She complained about Marge Piercy’s rape poem, and about a poster for women’s spirituality events being held at the Unitarian Universalist Church that had the words “Hecate,” “witchcraft,” and “Wicca” on it. It was ridiculous.

We won the fight, and the press got in on it. The Women’s Center was embarrassed. We were granted permission to stay without censorship. We made some concessions about how things would be displayed, and we weren’t censored. Then they elected a new president of the Women’s Center. The new president took Spring out to lunch and told her that she had to either remove all the lesbian books or move the whole library. This was when the director of the Women’s Center and half of the board quit. They were completely disgusted. As Cookie told me, those women are not used to losing.

The books went into storage, and then, to Our Own Place (OOP)*, which had one tiny room for them, shared with a pool table. We had to cull the collection. That hurt to lose these books we had worked really hard to amass. We went from 5000 to 3000 books. We donated some to the Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists (TALF) newsletter.** The books just weren’t getting used at Our Own Place. We had great support from the women most active in Our Own Place. Our Own Place was a funny place. It was used more by women coming in from other regions, from a hundred or more miles away, because they couldn’t hold hands with their lovers where they were. Here, it was a safe place in Durham. These were not ideal people to use a library, if they were only going to be there a couple of times a year.

* Our Own Place was a lesbian social and political group serving the Triangle area. From 1989 until about 1993, they rented a house in Durham for meetings, parties, and other events. The Women’s Book Exchange appears regularly in their calendar of events. See also our interview with Laurel Ferejohn about Our Own Place.

** The organization known as Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists (TALF) had disbanded before the 1990s, and a collective kept the newsletter they started, called The Newsletter, going until about 1993.

Meanwhile I had made friends with Martha Abshire Simmons, the director of the Women’s Center at Duke. The University of North Carolina did not have its own Women’s Center then. They wanted a library, and the Women’s Book Exchange needed a home. What was left of our collection went to the big, beautiful space at the Duke Women’s Center in 1993, where we made arrangements for it to be available to women in the community. We even worked out a deal so that they could park close–parking is a nightmare at Duke. They hired me to catalog the library on computer. Adrienne Rich came to inaugurate the new Women’s Center. [See Melody’s untitled address giving a brief history of the Women’s Book Exchange, which she read aloud to Adrienne Rich at a campus event.]

Eventually, I went on to work for other bookstores, and then, I went back to Chapel Hill, losing track of what was going on with the Women’s Book Exchange. The last time I visited the Women’s Center, the books were not there.

Southern Sisters, a Feminist Outpost

MI: The same sense of mission and the same passion for sharing information and learning from the people I met came with the Women’s Book Exchange and Southern Sisters. Sexual abuse was just starting to be talked about. The Courage to Heal came out the first year Southern Sisters was open. Rape crisis centers, and everyone doing any kind of work for women passed through Southern Sisters.

CT: I don’t think there was even a Women’s Center in Durham during the years we had Southern Sisters. The store acted like that. It was the place where all these people would meet, the Ministry in the South crowd, various independent newspapers we had. It was really a congregation of organizations that ebbed and flowed in the 1980s. If we had a dollar for everyone who looked at the bulletin board!

MI: The Durham Women’s Center had exploded in the early 1980s, before the store opened. Cris South ran the rape crisis center back then. She was an ex-partner of Minnie Bruce Pratt, and was my housemate for awhile. Cris is a minister now in Hawaii. Mostly white and mostly lesbians had been running the rape crisis center, sharing space with a related group. Was it for battered women? This other group was mostly Black women and mostly straight women.

The two groups got into a big fight, accusing each other of being homophobic and racist.

It just blew a fuse. We at the bookstore were filling that void. Years later, maybe 2000, or 2005, having dinner downtown with a friend, we saw two familiar looking women. They waved at me, and I waved back. After they finished their dinner, they came over to our table. They said, “We just have to thank you, and tell you our happy ending.” They had both moved to Durham separately, and had found housing together from our bulletin board. They were celebrating their fifteenth anniversary. It made my heart feel good.

We also had the Women’s Studies program. Duke had a kick-ass Women’s Studies program.

Rose Norman: How did Southern Sisters and the Women’s Book Exchange come together? Southern Sisters started in 1988, and the Women’s Book Exchange didn’t end until 1993.

MI: There was overlap. There was a time when I was doing both.

CT: Melody had been the manager of the Women’s Book Exchange, and we hired her to manage Southern Sisters from the beginning.

MI: You had a manager early on who didn’t do well. You had been in touch with me as an advisor, yet you had hired someone else, Dory, a woman who had worked briefly at The Regulator. She had a little bit of book experience. She was not antipornography, and she wasn’t cooperative. You fired her.

CT: I don’t even remember that. Melody is who I think of when I think of the store.

RN: Knowing nothing about starting a business or running a bookstore, how did you have the guts to do it?

CT: It was crazy!

MI: I still dream at least once a week about Southern Sisters. You’re usually there on the scene, Bibba’s there, and some of our customers. I am tearing my hair out, going over and over the inventory, because we don’t have money to replace the books we just sold, or to buy the special orders, or to get the new books that I know we need. That had been a recurrent stress for me.

CT: Bibba was more the brains of inventory control, and managing the money, which was sparse, trying to make it go on its own, which it would never do. I just had to put money into it week in week out. Bibba would figure out what we could afford to spend, and try to keep us in that.

I had worked in ladies ready-to-wear many years before that, and I hoped that books and t-shirts weren’t going to be the same. But they are. Exactly the same. Running an independent bookstore, small like we were, you did not get the price breaks the bigger stores got. Also, it was a time when everything was laborious. Everything was on 3” x 5” index cards. Nothing was computerized, and it was very labor intensive.

We also had a sidelines room. The greeting cards were a big, big feature. We also had pottery, women’s art, Snake & Snake Productions t-shirts, bumper stickers. We had an art gallery, exchanging art works every six weeks. We had art openings on Sunday afternoons. We tried everything.

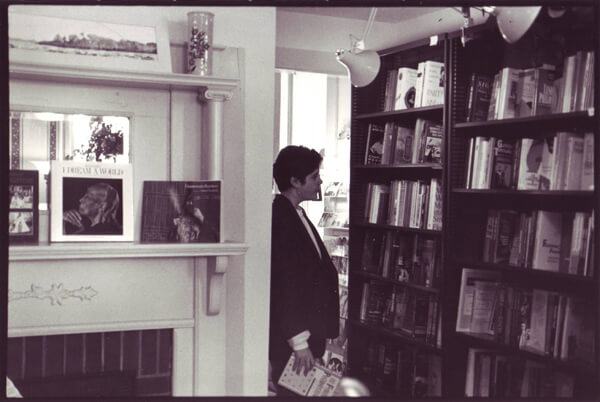

Another thing that was very successful were children’s books. Those books were beautiful. We designated an entire room that was gorgeous. That was my favorite part of Southern Sisters. That brought in a lot more people who would normally be scared of feminism, yet who were trying to be more progressive with their children. I was determined that feminism was going to look beautiful, not the bedraggled …

MI: Like the Women’s Book Exchange.

CT: People wanted to do used books, and I wouldn’t go into that either. We did art books, and that was the other thing we did with women. No one has ever touched this, and I bet that none of those other stores ever did it. We laid out the most beautiful stuff ever published by or about women, beautiful displays, gorgeous coffee table books. We really gave it a more sophisticated look. We were interested in women architects, women in business, women who did all these things besides the usual things you associate with women. It was an outpost. If you could have seen the way we presented women.

Nowadays, you can’t even find the feminist books in bookstores. More than 50% of what they’re selling are things other than books, just to stay in business.

RN: Melody, you told me a story about how the store was so beautiful that people weren’t sure it was really a feminist bookstore.

MI: One beautiful spring day, Alison and I both showed up to work in flouncy dresses. The first customer in was a very butch woman from out of town, and she saw this beautiful store with these women in flouncy dresses. You could tell she wondered if she were in the right place. I went and put on a Cris Williamson song, and she relaxed.

CT: That emphasis on beauty made it kind of an issue with some of the more hard-core lesbian community, who didn’t particularly support the bookstore.

MI: A lot of them, starting with Dory, objected to the antipornography stance.

CT: That, andI wasn’t going to give them any of the S&M [Sadism and Masochism] stuff. I remember talking to John Stoltenberg one time about some book we had that I didn’t like. And he said, “Well, that’s it. A feminist bookstore, and you’re out picketing your own bookstore.” I don’t remember what that book was.

MI: I had big fights with you about Jo Ann Loulan’s lesbian sex books. They were incredibly popular. They may have been what we sold the most of. It was not subject matter that would appeal to you, and yet, they were innocuous, not about S&M. Similarly, Naiad Press. You had no patience with Naiad.

CT: They were very poorly written.

MI: Jane Rule was good, and our customers wanted them. When Naiad came to town, to Our Own Place, and I took a table of books over there, Naiad offered to bring us books that they knew would sell. And then they stuck us with boxes and boxes of [unsold] books.

CT: Feminism was what it was about for me, hard core, feminist theory. Also, the late 1980s and early 1990s were about legal and critical theory, my main areas of interest. Everything else, I didn’t care. I cared not a whit for feminist spirituality. To me what happened to stall the women’s movement started in the 1980s when all that spiritual crap came along.

The self-help movement, The Courage to Heal, the crapola that was being produced ad nauseam. The spiritual books were the big sellers, and I had no interest in it. It was all too navel-gazing to me. And the American women’s movement still has not snapped back.

I do Facebook with radicals in their 40s, maybe kissing 50 years old, who are lesbian separatists, and who are very political. I don’t see any of that here in America, even at the universities. The University of North Carolina dropped the whole Women’s Center or library,whatever they called it. I had given them a lot of books, very high-end books. I had the entire nine-volume, bound collection of the History of Woman Suffrage [Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Ida Husted Harper, and Matilda Joslyn Gage edited various of those volumes in the 19th century]. I’m sure the library took that.

RM: Maybe you could talk a little about how you got into feminism?

CT: What happened to me as a straight woman and mother of three children, two step-children, two husbands—the whole nine yards—was learning about people I really admired like Andrea Dworkin. Not only were they lesbians, but they were Jews. There were all these smart, Jewish women; and books were our way out. Janice Raymond. A lot of those people were lesbians, maybe not practicing lesbians. It was too difficult to have those relationships. Now, I’m just thinking of our little band.

Politics was the glue. It brought lesbians and straight women together to the point where

a lot of straight women experimented with lesbianism.

I took a circuitous route to lesbian feminism. I ended up leaving my husband. I had a woman partner for a while, and that one did not work. I was always feminist identified, never really lesbian-identified. For me, the two were very interwoven. There was such a range.

The lesbian-feminist movement couldn’t have happened without all those other things, what was really a womanist community. With a few exceptions, like Audre Lorde, I guess it really was a self-absorbed, white women’s movement. Politics was the glue. It brought lesbians and straight women together to the point where a lot of straight women experimented with lesbianism. They certainly had crushes and fell in love with other women in the group. They learned a lot about that world when the lesbian world was undergoing a big change. Just when I was departing the bookstore, we got the lipstick lesbians, which to me, looked like these drag queens today.

MI: It was a highly contentious time, and women were ready to throw each other out of the movement over whether you wore make-up or associated with men. This was pre-Southern Sisters, and I went to a women’s peace encampment in South Carolina [October 1983], and then, to the first Southern Women’s Music and Comedy Festival [May 1984], and I was a closeted straight woman for a week.

The assumption was that if you wanted to be with just women for a week, you’ve got to be lesbian. That’s what the majority of attendees were, and of course, they were celebrating being in this safe space and being together. It was really fun. Women were telling stories about coming out, and how their best straight friend turned on them. I learned really quickly that the last thing I should do was come out to them as straight. I knew these women needed to tell their stories, and I needed to listen. I was very careful in the pronouns that I used, and I let women assume whatever they wanted.

I was cabin mates with women from the Seneca Peace Encampment. The most beautiful, brilliant, savviest of them came storming into the cabin after a meeting at the music festival. There was a lot of tension about how Robin Tyler was running the festival. She and other women from California were really condescending to the Southerners. Robin had made a speech about our being all dykes together, and how we should get over our differences, and I was cheering that. Then back at the cabin, this woman said that was a cheap thing that Robin had done, and that every straight woman here must feel alienated, and I came out as straight. Ironically, she was the first woman I had a crush on.

CT: It was very difficult to be a straight woman and to have credibility within the feminist movement, here and nationally. Of course, there were a lot of straight activists at NOW and other places like that. The movers and the shakers were by and large lesbians, not necessarily having sexual relationships. They were too busy being philosophers to have romantic relationships.

MI: That really was the height of lesbian feminism, and also of lesbian separatism. Those were the most radical, the most interesting things going on. That certainly influenced my feminism as I practiced it, as I understood it.

CT: If you want to work on dismantling patriarchy, start with the lesbian community. Then you found out that, even there, there was all this hierarchy. That’s where all the class and race issues came out. There was a lot of discrimination around education as well. And of course, the media made the whole world think that anybody who was a feminist was a lesbian.

RN: One thing I’m hearing is that the whole reason that both of you got involved with libraries and books was feminism, wanting to do something about women’s oppression.

CT: Absolutely.

MI: Absolutely.

CT: You make materials available for people who are looking for it. The bookstore is a place to publicize these things, to have talks and other public events. It becomes an outpost, being there for women. You don’t see that anywhere any more.

RN: And it seems that in this area full of universities, the Women’s Center was not the place to go if you were a lesbian. You needed the bookstore.

What I’m seeing that is hopeful are the intersectional groups, the people of color standing up against

police brutality, the organizing around reproductive rights

MI: That was true of the Orange County Women’s Center, even though the director was a lesbian. A lot of women who went there for help of one kind or another felt excluded. The women with the money there were older. They came from families whose names are on streets and university buildings.

CT: The Chapel Hill Women’s Center that was always supported by the elite, straight women, pulled out when it was decided to bring the Battered Women’s Coalition back in. All the wealthy women walked. They didn’t want the Women’s Center to be associated with this down and out group. That just happened last year. You know, you just can’t do feminism without lesbianism.

What we have in the mainstream is liberal feminism. I’m a radical feminist. I don’t look in America for much feminism any more. You really have to go to India, to Sri Lanka, where women are sticking their necks out to get things done. Here, it’s more like Hollywood style. It’s not about dismantling patriarchy. It might be about getting equal pay.

MI: What I’m seeing that is hopeful are the intersectional groups, the people of color standing up against police brutality, the organizing around reproductive rights.

MI: We were just talking about racial divisions within the lesbian-feminist community. Durham is a very racially mixed town. We had the joy of being involved with scholars of all colors from Duke in Durham [North Carolina], at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, at the University of Central North Carolina, and other nearby schools. It worked out at Southern Sisters that our most committed volunteers were a perfect rainbow, racially.

The late great Pearl Shelby, an African American artist, was very involved with the store. She helped raise my consciousness about the Black community in Durham. Illuminata Amat, daughter of Cuban immigrants, was very, very involved in the store, and she was our bilingual specialist. Those were the two outstanding volunteers, and the most committed to the store. There was also a lesbian couple who were graduates of a very strict Baptist divinity school. They had battled their way through it for women’s rights. They were also karate students, volunteer firefighters, and EMTs; and they were tireless volunteers for the bookstore. With that lineup, we accomplished a lot.

The customers were racially diverse as well. African American scholars came from all over. They appreciated our selection of fiction. If there was a new novel by an African American woman, it was on our shelves. We carried work from the small women’s presses. I did a happy dance when I found a novel by a minority woman from India, a native novelist from Canada. We had those on the shelves, and people felt welcome when they came in because we had those on the shelves.

I found a little, two-line write-up of the first book I had ever seen explaining how survivors of sexual abuse

could take their abusers to court. I knew that this book was really needed.

RN: This area is a bookstore mecca. Were you carrying books that no one else was carrying?

MI: Yes, we were. One of my joys was when an out of town visitor would say, “This is the best selection I’ve seen since Austin.” Or, “I’m from the northwestern U.S. How in the world did you know about this regional author from my area?” When the great and esteemed Catherine Nicholson [founder of Sinister Wisdom, among other things] wanted to put on a play at the local art center, she came in to look at our tiny little drama section. It was tiny; however, we stocked everything we found that was new and challenging. She found what she wanted to produce on our shelf, a Canadian play, a take-off on Shakespeare. Nothing could have made me happier than to supply Catherine Nicholson with the play she needed.

Like many booksellers, I read the spring and fall issues of Publishers Weekly, announcing all of the new titles for the season. One fall, I found a little, two-line write-up of the first book I had ever seen explaining how survivors of sexual abuse could take their abusers to court. I knew that this book was really needed.

I got in touch with the publisher, who turned out to be the author, who asked me how I found her. I said, “Because I was looking.” I made sure that the Feminist Bookstore News knew about the title. I made sure that our local attorneys, social workers, and psychiatrists who worked with survivors knew about the title. We added it to our bibliography of books on violence against women, and we sure as hell kept it in stock!

RN: Tell the story about the Louise Kessel’s storytelling workshop for the Women’s Book Exchange.

MI: Louise Kessel is an absolutely magnificent feminist storyteller. Back during the time of the Women’s Book Exchange, she had a six-week workshop called “Our Stories, Ourselves.” It was such a fantastic experience that it really became our consciousness-raising group. We were constantly finding out that we were telling each other things we had never told anyone else. There were about eight of us, meeting at the Women’s Book Exchange, before we were at the Women’s Center [at its original location at Carolina Library Services]. We couldn’t stand to give it up, and we kept meeting for two and a half years. Most of us are still in touch with each other.

We told not only autobiographical stories. We also did guided meditations, and wrote stories from them. The funny thing was that with our eyes closed dreaming, we all thought that everybody would interpret the prompt the same way, and that all of our stories would be the same. Of course, they weren’t. We came up with some great myths that way. Louise is still teaching and performing, living on an organic farm south of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is half Japanese, and half Jewish-white-Russian. Her father was a professor at the University of North Carolina, and she grew up here. She has performed with Pete Seeger. She also tells personal stories from the oral culture of every culture you can imagine. We’re hoping to do another “Our Stories, Ourselves” soon. A few from the original group are still here, and we will be open to new members.

How it Ended

RN: Where did you get the money to start the store?

CT: It was mostly me. It was a drain, and by the end, I said, “We have got to cut this faucet off.” The other partners gave some money, according to their means. I sustained it the entire time. It was a dream, and at the very end, maybe the sixth or seventh year, certainly by the eighth…

MI: The store only ran five or so years.

CT: Well it opened in 1988, and I didn’t close it until the summer of 1995. I went to real estate school that fall and got my license in 1996. It had to be 1995. That would be seven years.

It opened on 8-8-88 [August 8, 1988], which astrologists told us was a bad omen. I think they were right. We were always about $8.00 short every day, or eight sales short of breaking even. Another interesting thing about Southern Sisters is that when it opened, it got publicity; and when it closed, it got publicity.

CT: And after it was over, it took me years to talk about it. That was thanks to Barbara Lau. She had asked me to give a talk about Southern Sisters, standing outside the house that had been Southern Sisters. I was expecting the usual twenty people. It must have been eighty people, maybe more. And Barbara was fully equipped with microphones, the whole thing. What was nice was that there were some people in the crowd who had been in Southern Sisters. It was such a friendly audience. It felt so good. It was the first time I could revisit it. I didn’t even want to discuss it before that. It was like a nightmare to me.

That was everything cumulative. By the time I closed Southern Sisters, it was the cumulative amount of struggle. I had just called Duke University. They had been talking to me about my donating things, and I just told them to come pick it all up. I never looked at it again, never straightened it up. Lo and behold, they categorized forty or so boxes. Now, I think it was wonderful, yet you couldn’t have asked me that five years ago. I did not even want to talk about it.

It was always a struggle. You never got the breaks, the discounts, that the big stores got. Then there was a siege of break-ins. One guy just kept doing it. We got robbed a lot. It got old. We’d get these crazies. We took a class with Kathy Hopwood about how to stop them at the front door. You create the boundaries. And it was a good resource center.

MI: One thing we did was put together a four-page booklet called, “Resources for Survivors and Professionals.” [It was an annotated bibliography of books in categories like Child Sexual Abuse—Adult Survivors, and For Children and Parents.]

CT: People wrote for it from everywhere.

MI: That may have been our greatest single achievement.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Active Feminist Bookstores in the South (as of March 2024)

Long Civil Rights Movement: The Women’s Movement in the South, Interview by Stephanie Rytilahti with Melody Ivins, January 31 2011, for the Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007), at The Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

“Timeline of Feminist Bookstores in the South, 1970–1999,” by Rose Norman and Jennifer Scott, Sinister Wisdom 116 (Spring 2020): 39-53.