Diana Rivers: Author, Cultural Activist, and Grassroots Landyke

Interview by Rose Norman at Womonwrites on May 24, 2012

Divorced and alone in 1972, Diana Rivers paddled her way from New York to Arkansas with an unbridled fever that turned the local landscape upside down.

I first got involved in living on the land in community when I moved to Arkansas, from Stony Point, New York, in 1972. In New York, I had lived in a mixed community of artists and musicians. When I moved to Arkansas, we started a community called Sassafras, in Newton County, which was a community of women and men. Two or three years later, a new wave of feminism came through. Most of the women, except for one, either left and came out, or came out and left.

At a certain point, I had to go back up to New York, because my son Kevin had died. When I came back to Arkansas, the women were all eager to take over the land. There was a lot of anger. They wanted to take it over. I was probably older than most of them, and I kept asking, “What do you mean by ‘women’? Is it open to everyone? How are you going to deal with the men who are living here now? Would we deal with them fairly and kindly?” We had a horrific meeting – what for me, was a terrible meeting – at which all this anger came out against these men who were simply well-meaning, nice, hippie men.

It ended up with the women taking over the land. These women were suddenly empowered, and without knowing what to do with this new power, they acted out on each other in the worst possible ways. And it went on for quite a while. At some point, I went out west with my girlfriend. On my return to Sassafras, I found that the two communes that were on the land were feuding with each other. They were the Lesberadoes and the Blue Creek Tribe, mentioned in “Arkansas Land and the Legacy of Sassafras.” One of the two groups had guns. The other group thought that the way to deal with things was make a big circle around the place and chant, which felt like voodoo to the women who had guns.

Biographical Note

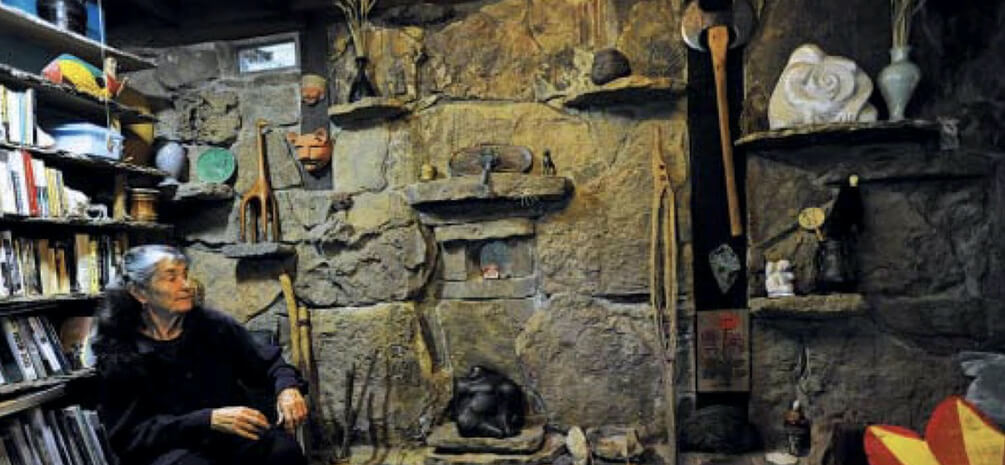

Diana Rivers, writer, artist, and political activist, authored the Hadra series of novels, all of which are available through Bella books; and Dancer for the Goddess, and Snake Memories and Other Stories. She co-organized the annual Women’s Conference and Festival at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, from 1990 to 99. She produced WomanVision, a women’s art show in Kansas City, from 1991 to 1993. Diana Rivers cofounded an annual, week-long Goddess Festival in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in 2009, still going in 2022.

There was an Ozark Women’s Land Trust (OWLT) in existence then. They were having a meeting, and they had heard about what was going on at Sassafras. They got in their cars and their trucks to go to Sassafras. The OWLT women said, “This won’t do. You’re endangering the women’s land movement. You cannot behave this way. We won’t have it. This group, you go over there. This group, over there. For a week, do not speak to each other, and do not have any interaction. Think about what you’re doing. We will be back in a week.”

The amazing thing is that when the OWLT women came back in a week, part of the discussion was about who was going to cook what for Thanksgiving dinner. We got over ourselves and resolved it. There was still a lot of infighting among women, a lot of horizontal hostility. If you felt like you were oppressed, it was like getting a ticket to be the oppressor. Now this is entirely my interpretation of it. However, I think other women would say the same thing. It was that abrupt empowerment, with no example of how to handle or use the power, except the oppressors’ examples. That community went through many turnovers.

The original mixed group called Sassafras continued to be called Sassafras after it became all women. At one time, it was all lesbians. Around that time, a piece of Sassafras land on the other side of the creek became what is now Arco Iris, designated as land for women of color, supposedly of all colors. Arco Iris is still in existence. What was Sassafras is now Wild Magnolia. I was the last person who signed it over to Arco Iris. Arco Iris is the umbrella organization, and Wild Magnolia is under that umbrella. They are making an Earth school there, bringing in LGB and queer kids from Little Rock and different places for summer camp. Different things were happening there. Sun Hawk, now known as Aguila, at Arco Iris could tell you more about this history.

Ozark Land Holding Association (OLHA), started 1981

Some of us left. What happened was that first, all the men got kicked out, then, all the white women got kicked out. For a while, all of it became land for women of color only, so we white women left to start another community, Ozark Land Holding Association (OLHA). Like Sassafras, OLHA is not a commune, yet it is communally-owned land. We didn’t all live in one building. We were scattered in different places on the land. You might choose this spot; and I might choose another spot to put a little hut or cabin or whatever. We didn’t have to all agree on things like where we built our houses.

Ozark Land Holding Association, OLHA, is a community of 240 acres in Madison County, Arkansas. There were 20 members for a long time. They weren’t all necessarily living on the land. Land changed hands because women would buy in, and decide they didn’t want stay there. Only about twelve women lived on the land. Some were very involved with the land, but they also had a house elsewhere. For several of us, that’s the case. We have 15 members [as of 2012], and we’re looking for new members. Of the 240 acres of land, each of us has 5 acres, leaving a lot of common land. It’s called a land-use contract with the community. You sign that land-use contract, and it has all the rules in it. And then you owe a monthly payment for house insurance, taxes, utilities, road upkeep, and upkeep for the main house, which is the community-owned house. We’re always trying to hold that main house together.

OLHA is all lesbians. OLHA was part of the legacy of Sassafras that was just for lesbians. We started this as a lesbian community. In fact, when we started it, such awful things had happened at Sassafras that it made us, the founding group, a very, very tight bunch of lesbians. In terms of the main house, nobody could claim space there. If you were building your house, you could maybe unroll your bedroll there. That wasn’t a system that worked. Now, we do things by contract. For example, if I were doing major repairs on my house, and I wanted to live in the main house, then, I would at a meeting ask for a contract. We have two potential rooms in the main house. I would pay for the room, and I would pay extra for the utilities. Maybe, in addition, I would mow the lawn and do some work around the house. That role would be mine for however long we had contracted.

Regarding the lesbian separatist land movement,I think that some of the women at Sassafras were separatists. However, I don’t see the women at OLHA as separatists. We all have men in our lives. We have invited men to the land. When I moved there, I said that I would not live anywhere where my sons were not free to come visit. In fact, my son, Sean, and my daughter-in-law recently came and stayed here for a week. We had a potluck, and I think Sean was the only guy in the room. He sat down next to Shell, who has had all these butch experiences, and the two of them got into a wonderful conversation. I don’t think any of us at OLHA would see ourselves as separatists, and yet, we’re living on lesbian land.

When some of the women in our group had been so vehemently separatist, I kept saying that I didn’t have that luxury. I had three sons whom I love and who would always be a treasured part of my life. I can’t be angry at all men. I can be angry at the male-dominance system, which also harms men. But there are men who are my brothers, who have given their lives to make the changes we want to see in the world. And besides, this was all a bunch of snooty, white women looking down on the men, and I thought, “What would women of color say to you? You didn’t ask to be in that white skin, but you are. A guy didn’t ask to come with that ‘equipment.’ Don’t get me started on that subject.”

Separatism: To be or not to be?

I do see the reasons for separatism. I had been involved with civil rights and peace politics long before moving to Arkansas. For a while, I was a member of the Congress of Racial Equality, known as CORE. Later, CORE decided they didn’t want any white folks, which I understand and honor.

I did a lot of peace activism, demonstrating, going to Washington. D.C. For a little while, I was involved with an underground, antiwar group in New York. We didn’t do anything violent. We only did non-violent civil disobedience actions in New York City, where we chained off 34th Street, and we dropped leaflets out the window. We chained off the West Side Drive. We let pigeons loose inside of Grand Central Station [in New York City].

The other Sassafras women were much younger, and for many, this new, Landyke experience was their first introduction to politics. If you look at history and see how men as a class have treated women as a class, it’s a miracle that we speak to any man and don’t want to shoot them all. For a lot of women, they were looking at all this history for the first time, and to them, it was as though all men had become the Taliban or something.

I came down to Sassafras when my marriage split up. I was 38, having gotten married at 18. At probably 39 or 40, I got involved with a much younger man, some 15 years younger than I. The other women at Sassafras were closer to his age or younger. They weren’t dykes to start with, as I said before, but they left and came out, or came out and left. Whereas at OLHA, we do consider ourselves part of the Landyke movement, and when there have been Landyke Gatherings, we attend.

When I think about it now, when we had that meeting with the men, if only we had sat down with them in a non-violent communication kind of way, and said, “Listen, the straight community is collapsing. Women need a turn, a chance to see what they can do with this. Why don’t we just amicably shake hands.” I think the men would have had a little caucus, and they would have said, “OK, it’s time to bow out.” But women were so angry. If you can give me something, that means you own it. If you can give it to me, then it’s yours to give. If I grab it from you, then I own it.

Postscript: Debra Gish asked Diana Rivers on July 15, 2022, if she were to repeat or live the experience over again today of organizing the Landyke communities, what, if anything, would she do differently, given the times we’re living now. At this point, it’s been 50 years since Diana first made her way from New York to Arkansas in 1972.

Diana said, “No, I really would not do anything differently, because I did everything that I knew to do, given the context and the circumstances at the time. I would like to have avoided the terrible conflict among us. But I’m not sure how to do that.” She recounted a time in which she was asked to mediate conflict amongst her own community members, and it didn’t go well at all.

“It’s important,” Diana went on to say, “not to ever assume that all lesbians will agree. It’s important to understand that lesbians are the most powerful yet damaged people in the entire world. This combination doesn’t permit easy compromise, especially when some are digging in their heels to exert their new power, or to protect themselves, while others are just trying to get along with each other. Maybe we should do more communication in the beginning, before we proceed as a community, to understand what women are expecting or hoping for in becoming a Landyke.”

The edited notes used in this interview with Rose Norman are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubinstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University, in Durham, North Carolina, along with the unedited audio interview.

This story was developed by Debra L. Gish from notes from the interview conducted by Rose Norman in 2012. The interview has been reviewed and approved by the interviewee, Diana Rivers.

See also:

Diana Rivers, “Sisters, Let Us Remember, Sinister Wisdom 124 (Spring 2022):5-18. http://sinisterwisdom.org/sw124

“Diana Rivers,” Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diana_Rivers

Debra L. Gish, “Diana Rivers: From Atheist to Pagan,” Sinister Wisdom 124 (Spring 2022): 41-45. For this story, Debra L. Gish interviewed Diana Rivers at Diana’s home at OLHA on October 17, 2019.

Merril Mushroom, “Arkansas Lands and the Legacy of Sassafras,” Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 36-42. http://sinisterwisdom.org/sw124

The story of women’s intentional communities in Arkansas is also told in the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Allyn Lord and Anna M. Zajicek. The History of the Contemporary Grassroots Women’s Movement in Northwest Arkansas, 1970–2000 (Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press, 2000).

Teresa Turk, “OLHA Seeking Members,” YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6WAAAhkrVAY