Red Dyke Theatre with Mickey Alberts and Frances Pici

Frances Pici, Mickey Alberts and three others started Red Dyke Theatre in Atlanta in 1974 with a New Year’s Eve show at their home, Tacky Towers.

Edited for the web by Merril Mushroom. Interviewed by Rose Norman and Gail Reeder at the home of Gail Reeder in Decatur, Georgia, on June 28, 2015.

Rose Norman: Tell us about Red Dyke Theatre in the beginning.

Gail Reeder: I have been living in Atlanta since 1978 or 1979. I’ve always been interested in theatre. I first got interested in political theatre when I was working for the Quicksilver Times in Washington, DC, writing an article on a theatre group called Earth Onion, from Durham, North Carolina. At that time, we were all Maoists; and there were traveling theatre groups that were raising the consciousness of the people in China. I was fascinated when I met Earth Onion. Here they were, doing it in America. Learning about Red Dyke Theatre was part of why I moved to Atlanta.

It all started with a flat motorcycle tire in West Virginia [shows photo of her with motorcycle], through which I met a mechanic, Stu. I went to visit him in 1975 in West Virginia when there was another woman there visiting. Her name was Winona Holloway. She said, “You should come to Atlanta. There’s this group there named Red Dyke Theatre.” That stuck in my mind. When I had an opportunity to move here from Los Angeles, I remembered that. One of the reasons I moved here was that I knew Red Dyke Theatre was in Atlanta. This is the woman who told me about it, Winona Holloway. [She shows picture of Winona with her Girl Scout troop].

Frances Pici: Winona! She and Marsha . . . Still?

Mickey Alberts: Still.

FP: When Red Dyke Theatre went to multimedia performing, they were involved with the film-making. There’s a picture of her in one of our rehearsals.

GR: But when I came to Atlanta [in 1979], I was quite disappointed that Red Dyke Theatre was already gone It’s amazing that in a house in West Virginia, with no running water and with a bathroom out back, I heard about Red Dyke Theatre. [She shows a picture of herself at that West Virginia house where she heard about Red Dyke Theatre.]

MA: Pici and I knew each other from Women’s Studies College at the University of Buffalo, and both of us came out about the same time there. We both had lot of difficulties with our parents. Pici’s parents lived in Buffalo, and mine lived in New York City. There was a lot of consternation about that. Part of our involvement with Women’s Studies focused on establishing Coffee Houses for women’s and lesbian entertainment. I started writing very angry poetry.

FP: I was more of a monologist. Mickey was more of a poet. I was a “comedic, raconteur, monologist.”

MA: That’s her education, her “almost-PhD.”

FP: The Buffalo [New York] Women’s Studies College changed my life. One of the things that we had at the University of Buffalo through the Women’s Studies College was access to a campus radio station. I think you were involved in this, Mickey. There were three women’s programs that started our creative adventure: “Women Power,” “Sappho,” and our reclaiming of soap operas called “The Ledge of Night.” “The Ledge of Night” was very popular. It aired in Buffalo on the campus radio station every week.

The music culture drove a lot of what we did. The culture of music in the 1970s was really activist and engaging, and we transplanted that into what we did on the women’s radio shows. When we had any type of composition of poetry, monologues, or skits that we created for the radio shows, we decided to take those to a live audience, as was customary, having a Women’s Studies College space for it. That grew into a coffeehouse. From the coffeehouse environment with an open mic, people would come with poetry and folk guitars. Compiling all these creative ideas and formats, we created Stars and Dykes Forever Theatre. I remember Mickey and I had the conversation that there was a lot of women’s and feminist stuff going on, but there was no exclusively lesbian stuff. This was the taboo that we have been faced with even within the women’s movement.

Back in the day, lesbians kind of played in the background of the women’s movement. I used to call it a red herring. Even though we lesbians were driving this movement, there were two issues we were told to back off on… in order for the goal of achieving the ERA not to be tainted by those two issues: Lesbianism and abortion.

Of course, we already had an attitude about that movement-inflicted invisibility. Here we were doing all this work, and we had to be in the closet in our own movement. So we wanted to make this public in our performance, as well as what we chose in our poetry, monologues, music, and creation of Stars and Dykes Forever Theatre.

MA: In Buffalo, we were in a tight, lesbian-feminist, Marxist community. But we started to feel some of that same exclusion in that community as we did in the broader women’ s community. That lesbian-feminist community was very dogmatic. I always considered myself femme; and that was not okay with that group. I was told that my long hair and hippie dress were showing my “bourgeois” background. I had to cut my hair short and wear flannel shirts. I was ostracized for being a femme who wanted to wear “the garments of oppression.” There were a lot of other rules in this lesbian-feminist, Marxist community. Pici and I don’t like rules.

FP: If there’s a rule in place, we will defy it, question it. Once again, historical context, we were defining a movement early on. In a Women’s Studies college environment, we were trying to develop some theories to go along with this practice of lesbian feminism. People were at the very beginning stages of identifying who we were, this invisible, closeted population. It was tricky because some people didn’t want to wear “the garments of oppression.” They wanted to make a statement that was totally counter to a feminine presentation of ourselves. One of the things that I was doing at the Women’s Studies College was that whenever anyone came out, we would do an extreme haircutting in the middle of the Women’s Studies College as a rite of passage.

MA: I cut your hair!

FP: That haircut was your badge in that early definition of lesbian feminism. In this definition, there was the issue of butch and femme, which in many cases was addressed through class.

MA: Yes, in the Women’s Studies College, butch and femme were okay for the working-class community, it appeared, because that was their roots, but we were not supposed to engage in that. We were supposed to be androgynous. Anything else was supporting the patriarchy. It was very hard line. That was one of the reasons I left. I was in graduate school in Women’s Studies, and it was just too much for me.

FP: The Women’s Studies College at the University of Buffalo came in response to all the activism on the UB campus.

MA: All that happened post-Kent State.

FP: There were events like the Anti-War Movement, the Wounded Knee uprising, the Attica prison riots, and the second wave of the women’s movement. UB at that time was considered the Berkeley of the East, a very radical university. We had at least 700 National Guard on our campus in the early 1970s, in formation, armed, and pointed at our “student body.” The administrations decided that to corral some of the student activism and unrest, they would create or let the groups create individual colleges and develop our own curricula.

MA: That was part of the students’ demands: American Studies, Native American Studies, Black Studies, Puerto Rican Studies, and Women’s Studies. That was part of the student leadership’s demands.

FP: We had some very progressive faculty. Elizabeth Kennedy was our mentor, along with Margaret Small and Ellen Dubois, who sponsored courses created by Women’s Studies. One of our demands was the introduction to lesbianism and lesbian feminism. We insisted that these be women-only courses. We had to really do some politicking with the administration because this was a public university.

Biographical Note

Frances Pici (known as and pronounced as “Peachy”) was born and raised in Buffalo, New York, in a Sicilian Catholic family. She attended the University of Buffalo from 1971 to 1974 and was a founding member of the Buffalo Women’s Studies College, which at that time was one of only two Women’s Studies programs in the country.

Mickey Alberts (born 1952) grew up in New York City and graduated from the University of Buffalo, where she also began graduate work in American Studies with a focus on Women’s Studies. Through the Women’s Studies College at the University of Buffalo, she met Frances Pici, whom she followed to Atlanta in 1974. Mickey was 22 when she and Pici started Red Dyke Theatre in Atlanta.

Red Dyke Theatre, Overview

Frances Pici and Mickey Alberts, and three other members of their communal household in Atlanta (Jeanne Aland, Murry (Mary) Stevens, and Carol Gallant , aka C.C.), started Red Dyke Theatre in 1974 with a New Year’s Eve performance at their home, which they called Tacky Towers.

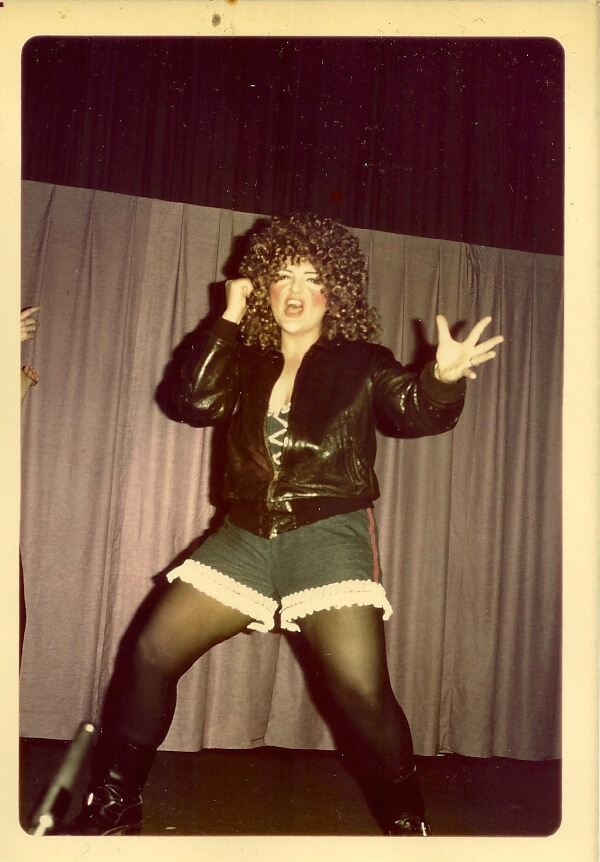

The theatre collective began as a response to the drag shows that were popular in the men’s bars, and they used the drag-show practice of campy dress (although the collective’s were usually from thrift shops) and drag-show choreography while lip-synching to popular music. Red Dyke Theatre also developed lesbian-feminist political pantomimes like “Coming Out to Parents” and comedic skits like “Superdyke.” They were deliberately reclaiming public displays of feminine sexuality and language commonly used to demean women with acts like “Gladys Peach and the Clits,” “Peach Midler and the Dykettes,” and “Dykeanna Ross and the Superbs.” They performed at gay and lesbian bars, the Metropolitan Community Church, the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA) House, The Great Southeastern Lesbian Conference (May 1975: http://outhistory.org/items/show/94), The Egyptian Ballroom in the Atlanta Fox Theatre (1978), and other venues, always donating any proceeds to lesbian or gay organizations such as the ALFA softball teams, the ALFA House, gay pride, or gay and lesbian causes. The group disbanded in late 1978 when they had to choose between taking the show on the road and holding down stable, full-time jobs.

We made the successful argument that these were consciousness raising courses about delicate issues. Once you introduce a man into the conversation, everything is directed toward the men. The women are quiet and don’t want to offend. Mickey and I had “cut our teeth” there on institutionalized radicalism. We could be the architects of it, but at the same time, we were restricted by the institution’s rules and guidelines.

FP: Getting back to what Mickey said about challenging certain roles, I wasn’t sure where I wanted to go with this. I was never super butch or super femme. I was a tomboy. And Mickey was no help because she’d have on a man’s blazer with a long skirt! (I was in love with her at the time.)

I think what’s important to say is that we were trained in an institutionalized, very new, Women’s Studies, lesbian-feminist environment. We gained so much from that, from feminist process, dialogue. First of all, the Women’s Studies College was full of dykes, young and old, and tall and short, and thin and round. It was like the mothership. I had found my people. When I came into the Women’s Studies College at age 18, I joined everything. I joined the budget committee, the curriculum committee, the financial aid committee, the governance committee, and the hedonist caucus! Our system of governance was very Maoist. We carried the little red book. I still have it.

MA: And dialectical materialism.

GR: It was more accessible than Marxism. I think Mao repackaged Marxism for the people.

FP: I think the institutions and the groups like the Women’s Studies College and the consciousness raising that occurred early in the 1970s, and really the late ‘60s, took some of those ideas and reinterpreted them to fit our needs. We had in our governance meetings, at the end of each session, criticism/self-criticism, where people would say what worked, what didn’t work, and what we could do better. Sometimes people got pretty personal. Mickey got some flack for her femme presentation. It was an environment where we were into critical thinking, and that was the deal we made. Those were the ground rules.

Mickey may have left Buffalo because she was fed up with that, but I think it was because she was so in love with me that she had to follow me, and that I lured her to come with me [spoken with humor].

MA: Although she had another girlfriend.

PF: Well, I wasn’t butch enough for you, and never would be. Let’s start right now by expanding what a lesbian relationship could be. It’s not limited to a partnership, not necessarily sexually directed or driven. And that worked out great for us. What is it, 42 years? I came out to Mickey. Can I tell this story? Mickey had just decided she was now going to be a lesbian, and I took her to the doctor to get her IUD taken out.

MA: I was a lesbian who was practicing heterosexuality for the first 20 years of my life.

FP: On the other hand, I’m 62, and I’ve tried just about everything that life has to offer except heterosexuality and folk dancing. Mickey and I went to the doctor. It was International Women’s Day, 1973. In the parking lot, after she has been exorcised of the IUD, I proclaimed my love to Mickey. I told her that I’m a lesbian, too. She looked at me and said, “I love you. You’re wonderful. But you’re just not butch enough for me.” To which I said, “Okay, let’s just see what we can redefine here because I want you in my life.”

Coming out was hard for me in the city of Buffalo, where my whole, extended family had lived for generations, a family that was both Catholic and Sicilian. Having that kind of upbringing as a dominant part of my life made my growing-up years very simple. Everything was either forbidden or compulsory. The hard part was figuring out which was which. I shared the same face as all of my family, so I was recognizable everywhere. It was just a matter of time before I was going to be outed, and that was danger in the city of Buffalo.

The two of us took a cross country trip to California in the summer of 1973. I was 20, Mickey was 21. We weren’t even far into the Midwest when I said that I wanted to leave college, leave my parent’s home, and leave the state. By April 1974, I had done all three things. I was in Women’s Studies about a year and a half when I realized I needed to do that. I fled the state for two main reasons. One was fear that my family would discover my ho…ho…mosexuality. And the other was the Southern women. “Oh, my! Honey, please!” So I left Buffalo, moved South, and said to Mickey, “Come on down!”

MA: We lived in a communal household in Atlanta. [Micky addresses Gail] Did you come to Atlanta during the time people were living in communal households?

GR: For twenty years, I ran one called the Highland House for Wayward Girls, an eight-bedroom house on Highland, where the Freedom Parkway is now.

MA: Our household was named Tacky Towers. [Later occupants of the house included: Jeanne, Murry, Murry’s son Adrian, C.C, Pici, and Mickey.] Okay, Pici and I got here, we were free, we were in the South, and we get involved in the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA).

FP: Gail said earlier that she was drawn to Atlanta because she heard of Red Dyke Theatre. I was drawn to Atlanta because of ALFA and the emergence of the ALFA softball teams.

MA: ALFA was fabulous. However, we encountered some of the same political correctness that we had in Buffalo. Again, I was criticized for wearing the garments of oppression. It was a few years later, and the movement had progressed. We had been rebels, and we were primed to rebel again.

FP: One thing that ALFA offered – and thank goodness for ALFA, the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance – was that it was a social and political organization that had a physical space that was a safe space. In our mission, ALFA was open to all women regardless of their degree of “outness” as a lesbian. Men could be allowed in only if under the age of 12 or 14, children of ALFA members. Men older than that were not allowed into the ALFA space. It was geared toward social space where coffeehouses could be held. There was an ALFA library that Duke now has. It was more of a business operation that was social, that offered entertainment, and that was safe.

When Mickey and I came out, we were challenging the restrictions that were being placed on the presentation of the lesbian feminist. How did we want to be perceived?

MA: We got experience for a couple of years in Buffalo. We had a little time for things to develop as to how we wanted to be.

FP: And we didn’t want to be censored. Within ALFA, we started a group called Dykes for the Second American Revolution, DAR II, because of a desire for ALFA to also be more political. (I think Duke has the meeting minutes of that sub-group, DAR II, within ALFA). [There is a four-page, lesbian-feminist manifesto for DAR II from the ALFA archive at Duke, dated 1976.]

MA: We fought about all kinds of stuff.

FP: We brought up these very things in that environment. If ALFA was open to all women, regardless of their degree of “outness,” then we should not be censored for bringing up uncomfortable ideas or contentious ideas about class or butch-femme roles, and so on, which would inevitably lead to censorship or restricting the way you can present yourself as a lesbian.

MA: I think ALFA was responsive to class issues in a lot of ways. But at that time, lesbians were, for whatever reasons, not allowed to be sexual. By that, I mean sexy. There wasn’t a lot of overt sensuality. Oh, well, sure – in the bars, after hours. But the lesbian feminist was kind of an asexual being.

FP: I totally agree:

MA: Of course everyone fucked like bunnies, or did something. I don’t know what they did. I don’t know if they “fucked.” That would not have been approved of.

GR: Particularly if dildos were involved.

MA: Penetration was not supposed to be part of lesbian sex. This discussion was not even really had. It was taboo.

GR: I always thought that ALFA was a support group, but that the women in it were not necessarily evolved enough to see beyond wherever they were. If ALFA was somewhat restrictive, closed, and hidden, it was because of the women in it.

FP: I keep going back to the historical context. We were a group of women who had just come out from the shadows, and we were now being visible. And it was dangerous at that time – and it still is – to be demonstrative about who you were: visibly butch or queer; or to hold hands with another woman; or to be demonstrative in any way that would bring the sexuality part of lesbianism to the forefront. That was not encouraged for good reason. It was scary. We were not safe.

I was on the ALFA softball team, the first lesbian softball team in the city of Atlanta league. We were out-front lesbians, and whenever we encountered teams that played us on public grounds, and that hated us, we made the conscious decision to tell them that ALFA stood for the Atlanta Light Fixtures Association. And then, we made a beeline for the cars and got out of there quickly. That situation shaped some of the conservatism, the timidity about not being too… “dykey.”

The flannel shirts and jeans were very comfortable, and maybe not the best way to display a sexy, hot mama. Although I really got turned on by a couple of people who had that look.

I think Mickey and I were driven by not wanting to be censored. There is a value in exploring things that are taboo. It expands your mind. You can refine it. If you’re working in a box, you can’t really go outside of the box regardless of where the box is placed.

MA: Talk about the bars and drag shows.

FP: Well, I have some notes here that might make a good segue to that. In 1974, we started Red Dyke Theatre in response to the lesbian community’s demand for a gay theatre presence that wasn’t male-identified.

We were surprised when we moved here by how many gay men’s bars there were in Atlanta. There were four. There was a place that the whole gay community gathered together, the Sweet Gum Head. The main presentation there other than the dancing was the drag shows with female impersonators, mostly gay men.

There were only two lesbian bars at the time, The Tower and Garbo’s. There was a third one on Ponce de Leon Avenue that was kind of mixed. But they weren’t show bars at that time, like Sweet Gum Head was. And the lesbian bars were very small. You either went to the gay men’s bars, or the lesbian clubs, or you went to both, as Mickey and I did. We got to know the drag queens, and we loved the culture. Coming from our interest in music, it was something that really turned us on. Getting people together around music and song was the main thing they offered.

Red Dyke Theatre was a response to our lesbian sisters who wanted theatre that was not male-identified. The other link was that the lesbian softball teams that sprung up after ALFA were sponsored by the various bars. So there was a relationship between the women’s bars, the city as a whole, and the three lesbian softball teams (and the team sponsors that encouraged people to frequent those bars). All of Red Dyke Theatre performances were benefits for the gay community, the women’s bars, ALFA, the softball teams, or any issue that was a legal fight.

MA: We did a benefit for the Mary Jo Richer child custody fight.

FP: There was a relationship between Red Dyke Theatre and not only the women’s bars, but the gay men’s clubs, a relationship that was underscored by all of our performances being benefits. We weren’t a corporation that charged money, living luxuriously on the profits.

MA: The people we lived with liked to dance and go to drag shows. By that time, we had switched over from women’s music to primarily R&B.

FP: We were in synch with where the community was going.

MA: That’s what the bars were playing.

FP: We at Red Dyke Theatre reclaimed a lot of popular music: Gladys Knight and the Pips, the Supremes… we reclaimed these songs by impersonating the female impersonators. We saw how women danced to “Midnight Train to Georgia.” So Red Dyke Theatre did Gladys Peach and the Clits, which was a reclaiming of that group. We used what was used in the gay male culture then, lip-synching. I think there’s something very special about lip-synching. It’s the ultimate reclaiming; and we were not really comfortable using our own voices yet. Even the gay men in the clubs, the female impersonators, were not using their own voices.

MA: Yes, live singing came later, quite a bit later. We lived in this house with a couple of funky people, and we were funky. We’d go to the bars to party, and we’d come home and dance. And we thought, “Wouldn’t it be fun to do a number?”

FP: Let’s have a show!

MA: We decided we wanted to do a show. We started rehearsing a few numbers just because it was fun. We invited a few people over to a New Year’s Eve Party. We went to thrift stores to get all kinds of funky outfits. Then we had a whole bunch of people over at Tacky Towers where we did our numbers, and they loved us.

FP: They did. We had a packed house. We have moving images and sound from some of these performances. It was the debut of Peach Midler and the Dykettes.

MA: All these names… you can probably tell that we were reclaiming words, but part of it was reclaiming it for our community, too. ALFA was not happy with us at first. Some ALFA members were not happy with us being sexual. In one of our numbers we simulate masturbation. We were out there!

FP: You were simulating? [laughter]

This was our mission [looking at RDT program notes]: The wording is initially the same as the RDT program notes in the ALFA archives, but it comes from another program that includes a mission statement. The program read from here is titled “Red Dyke Theatre presents Another Staged Climax: A Night of Television,” and it’s listed as “March 19, 1977, Metropolitan Community Church, 800 Highland Ave. NE, Atlanta, GA.” This is the show that had the skit, “Tit Witness News,” sort of like Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update.”

MA: [Mickey takes over reading] “In the fall of 1974, a group of women began living together in a household which became known as Tacky Towers. These women really didn’t have too much in common (the refrigerator had to be sectioned off between the Hostess cupcakes and the mung beans). But they did have a few of the same interests: theatre, dancing, boogying, lesbian-feminist politics, and huge egos.”

FP: I never liked that line. Who wrote that?

MA: I probably did.

FP: [resumes reading] “Two of them had been members of Stars & Dykes Forever Theatre in New York City. Another was a former Woman-Song Theatre member [Jeanne Aland, one of the founding mothers of RDT]. The Tacky Towers family started messing around with some songs, and they came up with a unique form of drag. By New Year’s Eve, they had worked up a little show and presented it to a party of dykes…With the sweet smell of success fresh on their fingertips…”

MA: I wrote that.

FP: [continuing to read from that program] “Red Dyke Theatre’s first show was a benefit for the ALFA softball teams in March, 1975. The show was held at MCC… In July, we put on a benefit…” That benefit was followed immediately by a performance at the Great Southeastern Lesbian Conference. [looking for the mission statement] Okay, here it is: “Red Dyke Theatre’s position (other than prone): We are a group of feminists who embrace a lesbian-feminist and anti-capitalistic viewpoint. The ‘Red’ in our name symbolizes struggle and revolution. It also is the color of passion, an important element in our lives. The ‘Dyke’ is in our name because as lesbians, as gay women, we are reclaiming the word Dyke, which has historically been used as a put-down. We are making the word our own, and making it stand for strength and unity. Similarly, we are reclaiming other words used to degrade women, such as pussy, tit, clit, and cunt. This is a way to verbally disarm the antagonists and to give us all a sense of strength… Red Dyke Theatre feels itself to be part of a new women’s culture.”

I’m having a hard time reading this. [The copy is blurry, and she hands it to Mickey.]

MA: [reading] “Creating a new culture within the old is a difficult task, and we are forced to make compromises. The music we use is not strictly by, for, or about women. Most of it is, however, the music coming from another oppressed culture. RDT feels a solidarity with the struggles of all oppressed groups, whether they be gay, third world, or poor.

“We use the technique of ‘drag’—yet we are not trying to be drag queens. We are women portraying women in non-stereotyped ways. Our appearance and styles are as varied as yours, each as important to RDT as you are to the community. We are struggling to shake off the negative self-image of women created by magazines like Playboy, the media, and society in general. We are trying to get in touch with our bodies and to see sensuality as one of life’s primary joys.

“We are a non-profit theatre collective. We want you to laugh, clap your hands, and dance with us. But we also want you to think about the issues we raise and about how we can all work together to be…”

MA and FP [singing out together]: “FREE!”

FP: This was our credo [handwritten at the bottom of the typed RDT position statement]: “Our main objective was to entertain lesbians, and not to educate straight people about lesbians.” We saw who our audience was. We wanted to entertain.

MA: And we’d entertain gay men. About 25% of our audiences were gay men. We performed at the Sweet Gum one time. Lisa King at the Sweet Gum loaned me a copy of her Diana Ross dress for me to use to be Dykeanna Ross. So we had some interactions with the drag queens. We had what I think was mutual respect. I think they respected us.

FP: We definitely brought a little more politics and context into the night clubs that was not there before. And that traveled even further after Red Dyke Theatre went away. I continued my relationship with the clubs as a solo performer, as a feminist mime and comic.

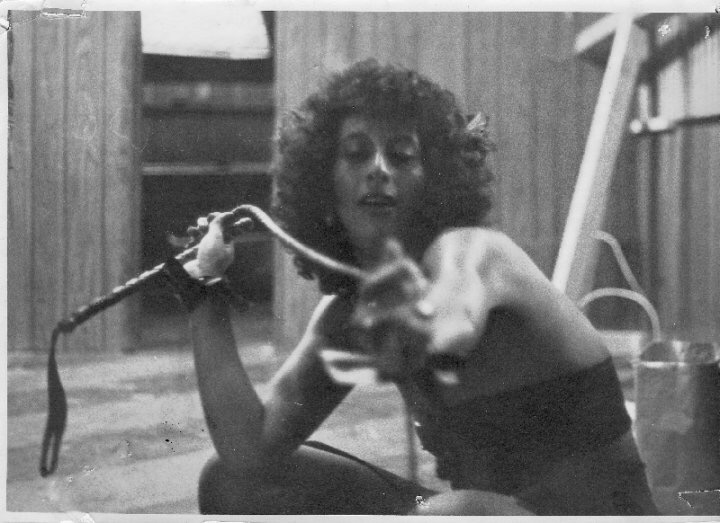

GR: I have pictures to prove it. [See closeup of Pici as mime. This is after RDT ended.]

FP: We were provocative. After each of our shows we had what we called a “talk back.” Sometimes we wished that we didn’t have to come back out for talk back because it was one of those criticism/self-criticism environments. Most of the stuff we were challenged on was about reclaiming words like tit, pussy, cunt, dyke. We even had a show called “Tit Witness News” that had a logo of two women’s breasts with eyeglasses on. The whole framework of the show was based on a news broadcast.GR: I do remember going to the Sweet Gum Head and seeing a lesbian comic there who had a penis puppet. It was Nancy Oswald. She did an act called “Dick and Dyke.”

FP: Some of the numbers we did that underscore this reclaiming include Dykeanna Ross and The Superbs, Gladys Peach and the Clits, Al Queen, The Pussy Sisters (a takeoff on the Pointer Sisters, and that one became a crowd favorite), Steam Heat.

MA: “Leader of the Pack” was one of our most popular numbers. Then we did an ensemble, “Don’t Leave Me This Way.”

FP: Right, Gloria Gaynor.

MA: No, that’s not Gloria Gaynor. That’s… Well, that was the whole group, and it would bring the house down. [Note: it was by Thelma Houston.]

FP: In the world of skits, we reclaimed the Superman show. One of our most popular skits was “Superdyke.” Superdyke’s alter ego was Clit Kent. Lois Lane was Closetta Lane. Fairy Wholesome was Jimmy Olsen. The character was a lesbian playing a gay man.

I was Macho White, spoofing Perry White. The bad guy that Superdyke would ultimately encounter was Scarface Smith. Unfortunately, we don’t have the 1975 version of that.

In 1990, Rebecca Ranson and SAME* did a retrospective of all the gay theatre in Atlanta from the 1960s to the 1990s. Jaen Black, who was also part of Red Dyke Theatre, and I re-enacted Superdyke, with new actors who were part of Rebecca’s group. We have that performance on film. For that, SAME also re-enacted a mime piece called “Coming Out to Parents.” I had created that piece back in Buffalo as my exit mime for leaving Buffalo. We did that in Red Dyke Theatre.

[*Note: SAME stands for Southeastern Arts Media and Education. Rebecca Ranson was the Executive Producer and the director for SAME. Deb Calabria was one of the SAME actors and writers, along with many, many other volunteers. Ranson wrote one of the first AIDS plays, Warren, based on interviews with AIDS patients in 1982 and ‘83. See also Rebecca Ranson, b. 1943, playwright and author, papers at Emory, http://findingaids.library.emory.edu/documents/ranson1253/]

MA: Saturday Night Live was just kicking off, and we kind of modeled ourselves a little bit on their skits, like our news program was sort of like their comedy routine, “Weekend Update.”

FP: It was very stable. There was a core group, the group that started in Tacky Towers: Pici, Mickey, Jeanne Aland, Murry (Mary) Stevens, C.C. (aka Carol Gallant). And later in 1975 : Jaen Black, Fanny Fernow, C.K, Donna Price, Harriett Green, Bonnie Netherton, Debra Gray, Wilson Huff, Dino Martin, Sue Berry, and Sarah Holmes.

MA: Jaen left, though, and moved California. [She’s back in Atlanta now.]

FP: Whenever she came back to Atlanta, she was such a comic genius that we had to put her in. I would say Jaen was ongoing. She wasn’t really a core member, but so valuable a member.

GR: She was also a musician, too.

MA: Right. She was in Moral Hazard.

GR: Moral Hazard performed with Tammy Whynot [Gail’s comedy persona] as the Even Strangers.

FP: Jaen straddled a lot of different places, and she also moved around a lot.

We had a technical lighting and sound crew: C.K., Debra Gray, and Sue Berry.

MA: We’ve always had a separate sound person, since sound was so important. Sue Berry and C.K. were our sound women, They had tape decks and all kinds of equipment.

FP: And our sound was the best. Perfect! Impeccable! Sue’s Nakamichi tape deck and our group-owned TEAC reel-to-reel deck.

MA: Rest in peace… another person who’s gone was our light person, Debra Gray.

For the shows, we had to borrow or rent the equipment that we did not own.

FP: We were very incestuous.

MA: Some of us were monogamous. Me and Jaen.

FP: Harriett and I. But before we were monogamous, I was with Jeanne and then with Murry. Back then, there was experimentation with non-monogamy. The ALFA softball teams were like that, too.

GR: On the softball teams, sometimes people wouldn’t throw balls to each other because they were mad.

FP: I was the catcher for a couple of seasons, and I could see everything that was going on in the field. There was a lot of drama. There was a lot of experimentation, but at the same time people wanted the stability of a relationship. That was before the AIDS crisis, so there was a lot of sexual freedom. Given all that freedom, why would we be partnering up and becoming exclusive?

GR: And there wasn’t another image to replace the butch-femme couple. We were really just making it up as we went along.

FP: We were flying the plane and building it at the same time.

MA: And gay marriage wasn’t even remotely on any agenda.

FP: And monogamy was really counter to the way that our subculture was developing organically. Thinking back on it now, I’m really glad we all experimented and tried to be inclusive rather than exclusive. I really don’t think monogamy was a model we could embrace and be successful at it, given all the organizations we were in, like ALFA, the softball teams, RDT, etc.

MA: No, it didn’t.

FP: And I would say we always functioned as a collective. Murry had a son, Adrian; and we all raised that child. Adrian, aka “Booger,” was about a year old in 1974.

MA: When you broke up with Jeanne and brought Harriett in, Jeanne just… retired from the group.

FP: Yes, she did. [Harriett didn’t live in the house.] Later Jeanne moved out, and I moved out, too.

MA: Two years?

FP: Me, maybe three –1974 to ‘77.

FP: That’s where Bonnie comes in. We rehearsed in her house on Elmira Street because we didn’t have Tacky Towers any more.

MA: We had to move because they sold that house.

FP: There was a core group [in Red Dyke Theatre] that stayed throughout. As people’s relationships changed, or new girlfriends came along, we were so involved with Red Dyke Theatre, and they didn’t want to be Red Dyke widows (like the softball widows). People could come into Red Dyke Theatre, starting out as technical help. We were getting to the sophisticated level where we needed sound, we needed lights, we needed the venue, and we needed marketing management.

MA: A stage manager. We always had someone to be a stage manager. Toward the end, we decided that we needed a director for each show. For a while, it was very egalitarian. Nobody was in charge. It’s amazing how it all happened. Toward the end, we decided we needed someone designated as in charge of the whole thing.

FP: That was one of the women in the group, in the show, who just had the bureaucratic responsibility to make sure that the contracts were signed, the costumes were here, and at the same time, she performed. No one really wanted to be the director, because they were also performing. But we had to embrace that role in order for the show to go on. Donna Price was another person in the group.

MA: We probably had none or ten people involved throughout, counting the core group and other people coming and going. It was not always the same nine or ten people, but always that number involved, and about two-thirds of them were performing, and the others doing technical work.

We wrote things collectively. We had overnighters, brainstorming. [She said to Pici] You remembered someone going in the other room…

FP: Wilson Huff had this great idea. Now that she had come out as a lesbian, she no longer needed women’s reproductive things. And she decided… [She said to Mickey] What did she do?

MA: She went into another room and wrote a whole thing about tampons and feminine hygiene.

FP: And she created all these little toys that she made out of these objects that she wasn’t going to use any more.

MA: Birth control.

FP: Birth control. She wrote the most hysterical skit that everybody loved. It was called “InnaHuff.” She would get up there like Julia Child and explain all the new uses for these things. And she just said, that night [that she wrote it], “I’ve got to go in there. It’s on my mind. I’ll come out in a few hours.” She was in there all night. She came out and I think she performed that piece with very few edits.

MA: Right. We would do group writing, or sometimes a couple [of us would write together]. I know that Pici and I collaborated on quite a few things. We’d rehearse our choreography quite a bit. The process was communal, and there were really no leaders. Even the director was not a leader; just someone with more responsibility.

FP: Because we all came from a living collective, our model of creativity was that everybody had a voice, everybody had equal time, to some degree, on the stage. We had to balance out the different pieces of the show to make sure everybody had enough time on the stage and everyone participated. At the same time, we were meeting the needs of our audience, who wanted to see certain skits again, like Gladys Peach and the Clits, Leader of the Pack, or Dykeanna Ross.

One thing that we did that the audience embraced, which they brought from the gay male clubs, was that the women audience members would come up on the stage while we were performing to stuff money or notes down our dresses. Or come up and just give us a kiss. This was a ritual that happened and still happens in the gay clubs, and it transferred right into our shows. Early on, some of the hard-line, lesbian feminist were very critical of this display. One time, Elizabeth Knowlton brought Charlotte Bunch to one of our shows at MCC, and she said, “I have a feeling that I’m not going to like this show.”

MA: Who said that?

FP: Charlotte, because she’d heard about women coming up on stage and putting money down our dresses. But surprise, surprise, Charlotte Bunch was so thrilled at how that dynamic unfolded. To her, it represented women coming out of the closet, presenting themselves on the stage, being physical with another woman in a public venue. She also thought it was a great bridge between the lesbian community and the gay community. That was one of our successes where we showed that we were appropriating things for the common cause.

MA: And people didn’t really put stuff… They were very shy, and they might press a dollar in my hand.

GR: The first time I was on stage at the Sports Page, and somebody came up and put money down my bra, I forgot the rest of my piece. I was so surprised.

FP: It’s a challenge when you’re lip-synching. And we were pretty good at that, at keeping the choreography going even though there was a line of women waiting to come up to kiss you, to touch you, or to hand you something. But on the balance, we thought, what’s more important here: this interaction or missing my mark? Our shows were interactive. There wasn’t a strong dividing line between the audience and the stage.

GR: Don’t you think the audience felt like they were almost part of you because you were giving them images of what they wanted?

MA and FP: Yes.

MA: A lot of our shows started with slide shows.

FP: When the music started, I’d be backstage with the slide carousel ready and waiting for live music cues.

MA: We’d take pictures in the community a lot. So in those slide shows there’d be pictures of people in the community, like the softball team or gay pride. That’s another way we brought the community in.

FP: The good news is that… we have that to show you. In the Lily Tomlin videotape, the one that was funded by Lily Tomlin, we captured that show. It has the beginning of all of our shows, which was a slide show.

FP: Lily Tomlin came to Atlanta to do a weekend of performances at the Great Southeastern Music Hall. Amy Darden, now Amy Estelle, and I went to the first night of the show, and Lily Tomlin commented in the show that she was thinking of doing a new character who was a construction worker, but that she needed to find the equipment to develop the character.

Amy contacted Lily Tomlin and told her she worked for the cable company, offering to bring the equipment to the next show for Lily Tomlin to buy from her. Lily agreed, and Amy invited me, Jeanne, and some other Red Dyke Theatre people to have a backstage audience with Lily Tomlin. So we’re all sitting there in Lily Tomlin’s dressing room in 1975, and Amy’s got all her cable gear. Lily said this is exactly what she had in mind, asks how much, and Amy said maybe $250 and tells her to make out the check to Red Dyke Theatre. That’s when we invited her to come to the show the following weekend [“The Great Southeastern Lesbian Conference,” see attached pdf]. She said she couldn’t make it that weekend, but instead wrote out the check for $450 so we could videotape the show and send it to her.

MA: [referring to the laptop with DVD] Back then, it wasn’t like this.

FP: Back then it was, I think, on two-inch tape. Marcellina and Marsha Still filmed it, and maybe Winona. I don’t know if Winona was involved in that. She was involved in the one we filmed with Bonnie [see Bonnie Netherton’s interview about that skit.]

Debra Gray and Bonnie were lovers at that time. Debra had a house where we rehearsed. Bonnie wanted to bring in more serious, non-comedic skits. She wanted to do something on rape called ‘On Trial.’ We did a multimedia thing where we filmed it. Bonnie definitely introduced a more serious tone to our skits. The one on rape was pretty rough. She did one other thing with Vickie Gabriner that is also on our tape.

[Rose shows them notes from an interview with Bonnie about a skit called “Emotional Insurance.” Bonnie and Debra did a skit naked behind a scrim, depicted thus in shadow. A theatrical scrim is a translucent stage curtain that can be lit to conceal, reveal, or shadow what is behind it, or to reflect slides.]

FP: A lot of that has survived and been digitized. First we put it on VHS, then VHS to Beta, then Beta to digital.

[At this point in the interview, Pici plays some film clips from a DVD. She and Mickey comment on them. All of that is recorded, but most of it is recorded music. Some excerpts below with photos.]

The original tape in 1977, from which most of this is taken, was on 2-inch, reel-to-reel tape that spent 15 years in an attic. Some of the film was wrinkled. They restored what they could. This is the film that Lily Tomlin funded. Other clips are from a 1990 re-enactment that was sponsored by SAME (Southeastern Arts Media and Education), along with other theatre groups from the period.

1. Peach Midler and the Dykettes – lipsynching to “Leader of the Pack.” (This is from the film that Lily Tomlin funded.) Pici is the lead singer (center), with Murry Stevens and Mickey Alberts as the Dykettes. This has the masturbation simulation at the end (Mickey).

2. The Android Sisters (take-off on the Andrews Sisters) sing “Well All Right!” (Murry, Pici, Mickey are the trio. Donna Price and Jaen Black come out from the sides briefly). Their thrift-shop costumes are designed by Amvets and the Vaudeville-style placards designed by Sally Gabb. This was at the MCC (same show as #1).

[Talks about but doesn’t play “Stilla Clerk,” which Pici calls “our homage to the closeted store clerk.” This involves interaction with a store mannequin. “One of the things we tried to show was women touching each other,” Pici adds.]

3. Dykeanna Ross and the Superbs, with Jeanne Aland, Mickey (as Dykeanna), and Pici. Dykeanna’s dress is borrowed from Lisa King (a drag queen). Otherwise, thrift store clothes. This was at the MCC (same show as #1 and #2). Depicts audience members coming on stage to put money in their dresses. Pici sais, “It’s kind of like Inception. We’re imitating female impersonators, but we are reclaiming the femme role.” Pici said: “Music like this really turned on our audience, too.” Rose notices that one of the audience members coming on stage to tip is African American. She asks if they had many African Americans at their shows. Pici said, “Yes, a proportion.”

4. Gladys Peach and the Clits: Pici as Gladys; and Murry, Mickey, and Jeanne as the Clits (wearing bell-bottomed, white pantsuits). This piece (but not this performance) is what Charlotte Bunch saw. Mickey said: “This was one of our big numbers. The audience would go wild!” Pici said: “One of the bar owners at the Tower would save up her bar tips and put them in a Seagram’s bag to tip me whenever we did this song.” Pici said: “The thing we really perfected here is the choreography.” Audience members are coming on stage with tips (comments about who they are). Pici said: “There’s something empowering about audience members coming up on stage.”

5. Al Queen, Murry lipsynching Al Queen’s “Here I Am.” Sally Gabb did the signage. More examples of audience members putting money in the performers’ dresses and kissing them.

6. The Cleverly Sisters, Jaen Black (at that time, she was Mickey’s girlfriend) and Donna Price dress like the Everly Brothers. The song is “All I Have to Do Is Dream.” Pici said,“I remember when we did this. We wanted to showcase butch women being physical and affectionate with each other.”

7. Superdyke, re-enacted in 1990 for the SAME show, “Family Album.” Deb Calabria, a SAME actor not in the original RDT cast, emceed the SAME event and introduces Superdyke. Jaen Black is Superdyke. Pici is Closetta Lane. Lenny Lassiter is Scarface Smith (she was also not part of the original RDT cast). [Fast-forward to next piece.]

8. Coming Out to Parents, Pici re-enacts this mime piece that she originally created for Stars and Dykes Forever in Buffalo, New York, and that she also did for Red Dyke Theatre. (1990 re-enactment film).

9. Slide shows – filming of slide show at the 1975 performance, the one that Lily Tomlin funded. This one compiles still shots from rehearsals. The song, “Stonewall Nation,” was written and performed by Madeline Davis. She was a songwriter in Buffalo who became a well known commentator on butch-femme issues. Again, the signage on the placards is by Sally Gabb. One of the stills shows the Red Dyke t-shirts. Another is Murry’s son at a rehearsal. The Pussy Sisters. Winona Holloway. Marcellina’s tattoo. Debra Gray, Sarah, light techs. Then, it shifts to the music usually used for slide shows (“Mr. Sandman”). Wilson creating “InnaHuff.”

RN: Tell us when and why RDT ended.

FP: When we decided to dissolve it in late 1978, it wasn’t because we weren’t good or that we weren’t interested. It was because we had to decide whether to travel, to go on tour, or to get jobs.

MA: Or to keep our jobs. Pici and I always did have stable jobs pretty much our whole work career. Other people in the group were a little more fluid, maybe. You and I weren’t really ready to give up our jobs, having been raised by Depression-era parents. We wanted the security of a job. Other people in the group would have wanted that, too.

FP: And these were not big salary jobs we had. We were making women’s salaries, and we were very young.

RN: What were your jobs back then?

MA: At the time I was working for Family Children’s Services as a case worker. At first, I worked for a year as a clerk at the Department of Revenue, just to get into the system. Then, I worked as a case worker, and moved over to Disability Adjudication Services. I was director there for six years before I retired.

FP: Four of us, Jeanne, Donna, Johanna [not involved in RDT], and I, deliberately sought non-traditional jobs because we knew that’s where the better salaries were. We targeted places with government funding that had to follow affirmative action, which required them to start hiring women into jobs that weren’t just administrative assistants. Lorraine Fontana was the first one to get a job at Xerox as a service technician. She told me about it. She asked if I could use a screwdriver, and I said, “I’m a great actor. Let me in!” So I started working at Xerox as a technician with a bunch of Vietnam vets. Those were strategic decisions we were all making at the time.

One of the things about the jobs in the early 1970s, when people were coming out as lesbians, one of the first things that we knew was that we were going to have to support ourselves. In that environment, there was no chance that family –husband, uncle, brother, any male – financial support would come our way. As it is now, a job was our livelihood, and it was the key to any independence we had created in choosing to live who we were as lesbians.

GR: And there was no corporate sponsorship.

MA: And that would have been totally against the group’s politics. We would never have considered that, never.

FP: Absolutely not. If Coca-Cola had wanted to jump on Red Dyke Theatre, we would have said, hell no, we’re will not be co-opted. Our working theatre group decided to fold because we couldn’t do it any longer, and to keep our jobs because our shows were not for profit.

RN: Did you decide that in a meeting?

FP: Yes, we had the discussion, and we decided that we were either going to do it as a group or dissolve. If people wanted to go on, they should start a new group.

I performed as a solo act until about 1984. It was a similar model, doing benefits for women’s organizations, lesbian organizations, lesbian causes, gay pride.

This was more of an avocation that I did along side of my [regular] job, a lot of which was working in the women’s bars. For a couple of years, I emceed the Tuesday night at the Sports Page, on “quarter beer” night [when a beer only cost 25 cents].

I have some stirring images of my performances in the early 1980s. Then in 1984, I put the whiteface away, the mime went to sleep, and I started working at CNN. Any performing I’ve done since then has transferred that performative energy into academic conferences; scholarly presentations at universities as a graduate and PhD student; working with feminist and gay/lesbian theatre groups such as SAME [Southeastern Arts Media and Education]. The way that I transplanted that performative energy (and still do) was more as an avocation related to performance studies, women’s studies, mime, and comedy.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewers and interviewees, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University.