Merril Mushroom: Lifelong Feminist Butch, Radical Advocate, and so much more

Interview by Rose Norman, September 20 and 21, 2024

Family Background

Rose Norman: Merril, give us some background about who you were before you became what you think of as an activist.

Merril Mushroom: That’s so Southern, to ask who was I, and who were my people. I was born and raised in Florida, Miami Beach, during World War II. I remember lots of servicemen marching in the streets when I was a very, very little girl. My family was involved with Russian Relief, the Red Cross, and wartime positions, because we were on the coast, like aircraft spotters and submarine watchers. We were not safe. There were German submarines offshore. We had electrical blackouts because if the lights were on in the city, then the submarines could see our Allied ships out in the ocean, silhouetted against the lights. The blackouts were for the safety of our own ships.

At one point, a Norwegian ship was torpedoed and sunk off the coast. They brought in the survivors, and my grandmother, who headed up the Red Cross, made uniforms for them. They were so tall and she was so tiny that she had to go up and down a stepladder to measure them.

I remember playing at the Red Cross with all kinds of threads and little sewing implements. That was when I was very little. I guess you could consider that activism, what my family did. My mother and her sisters went up on the roof with binoculars to watch for enemy aircraft. They had two-way radios that they could call in if they saw something.

RN: Do you have siblings?

MM: I’m the oldest of four. I have one sister, who lives in Canada. She escaped. [Laughter] I had two brothers, and now I have one. The other one also escaped, but in his own way.

RN: Your father was an entertainer.

MM: He was a puppeteer. He was a famous puppeteer for the times. It was during the vaudeville days, and he worked in New York City at the Roxy, and also Radio City and the Apollo. He was on Cuban television a lot, and he was on American television. He was on the Ed Sullivan show twice when it was called “Toast of the Town.” I have a recording of those that my sister sent me. He was on with Louis Armstrong.

Biographical Note:

Merril Mushroom: I am an old, Ashkenazi, rural, feminist dyke, and many other things as well. I was born 1941, in Miami, Florida; and I came out in the 1950s in the Miami Beach gay bar scene.

I’ve worked for a paycheck as schoolteacher, taxi-driver, motorcycle courier, waitress, construction worker, educational consultant, and training-materials writer.

My community service focuses on poverty, foster care, public health, special-needs kids.Fun and recreation for me include involvement with lesbian organizations, working in my gardens, maintaining the land where I live, putting up food, making botanicals, cooking for friends, playing bridge, doing word games, zooming with lesbians, reading, writing, and noticing what’s around me.

My father was the first marionette artist to do his marionettes at the front of the stage instead of from behind the stage. He used the black light, and he wore all black. He had fluorescent paint on the puppets and they had fluorescent costumes. He also did Punch and Judy shows, which were pretty typical. He made all of his own puppets, marionettes, and scenery. I used to watch him make all that when he was home, which was not very often because he traveled a lot. He worked with the USO many, many times during the Second World War and during the Korean War. I don’t think he went to Vietnam. I think he kind of settled back home by then.

The Miami Beach Years: Anti-Semitism, Racism, and the Johns Committee

RN: Speaking of the war, your family is Jewish. Were you aware of what was happening to Jews?

MM: I’m not sure how aware the adults were. I was very young. My grandfather, along with other folks, was trying to get family members out of Poland. But the U.S. was not admitting any more Jewish immigrants.

It’s interesting how Miami Beach was originally settled by people from the North who were escaping the Jewish presence in the North. They set up what was supposed to be a gentile town, yet it ended up being a majority Jewish population. I don’t know where all the Jewish people came from or why they came. A lot were Holocaust survivors, and a lot of older people had numbers tattooed on their arms. Even so, there was a lot of anti-Semitism. There were hotels that were restricted against Jews, clubs that were restricted, and beaches that were restricted. Restricted meant “no Jews allowed.”

RN: Was there a big sign, or what?

MM: They had big signs. “No dogs or Jews allowed!” I remember another sign that read: “Ocean view. No Jews.”

RN: They said the same thing of Black people, too, right?

MM: Yes, Miami Beach was restricted. Black people could come to the town of Miami Beach to work in the houses as cleaning women and such, or as yardwork people. But they were supposed to be off Miami Beach by 7:00 at night. We had “sundown” laws, which were fairly common throughout the South during that period of time, when African Americans were not permitted to be in the vicinity after a certain time of day, around “sundown.” Otherwise, they risked jail or worse.

A lot of the rich, gentile people that lived in the northern part of Miami Beach had African American household servants, and they hid them, letting them stay in the houses overnight. These servants had their own rooms, but they had to be very quiet about it. It was a nasty time. I remember when the Supreme Court ruled that separate was not equal, and we won the famous case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, in 1954.

RN: In 1954, you were twelve or thirteen.

MM: Yes, I remember that, and all of the riots. Actually, the riots on Miami Beach were aimed more towards the Jews than the African Americans. There was a synagogue that was bombed, and then another synagogue that was almost bombed. Our schools were not integrated, and the racial situation was the reason the Johns Committee got started. [The Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, commonly called the Johns Committee, after Charlie Johns, which conducted investigations of lesbians and gay men in Florida in the 1950s through the 1960s.]

There was so much in the way of tension with people acting out in the South after Brown v. Board of Education that some of the states were setting up legislative committees to try to prevent incidents by watching civil rights organizations and activist organizations and anarchist organizations.

The Johns Committee was originally set up under Representative Henry Hand to prevent violence by monitoring civil rights activities. When Henry Hand left Congress, and Charlie Johns took it over, he really went full-scale “Joe McCarthyism,” because it took place during the McCarthy hearings. Charlie Johns thought Joe McCarthy hung the Moon, and that he was the best possible person to know how to purge our great United States of all of this “terrible element,” meaning anything besides straight white men.

He did not have a lot of success doing that. Reverend Theodore Gibson, who was the head of the NAACP at the time, took Charlie Johns to court for civil rights violations. Johns wanted to prove that the NAACP was a communist front. When they went to court, Gibson won, and Johns was proved wrong. Johns could not harass the African Americans anymore. This is all in the article about the Johns Committee.

See numerous articles on this, including Merril Mushroom, “The Gay Kids and the Johns Committee” in Crooked Letter I, ed. Connie Griffin (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2015), 123–34; and Merril Mushroom, “The Gay Kids and the Johns Committee,” Older Queer Voices: The Intimacy of Survival.

Gay in Miami Beach

RN: And you came out in those times.

MM: I came out in those times. In the 1950s, we had a big gay and lesbian population in Miami Beach. We actually had a gay ocean front beach, too. In 1954, a gay guy was murdered in Bayfront Park by a couple of teenage hustlers. The newspapers grabbed hold of the case and blew it up really, really big. Then, all of a sudden, the Florida Sun [South Florida Sun Sentinel] got in on it, and they reported that gays and lesbians had invaded Miami Beach. They said that we were out for the sweet young flesh of people’s children, and folks had better watch out! There always had been a few police raids, but now, there were a lot of police raids. The newspapers printed the names and addresses and places of employment of anybody that was arrested.

You could be arrested for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The law had like 24 different counts of vagrancy they could use to pull anybody in. If the person was gay, they were in big trouble. The police could keep them overnight “on suspicion.” If there was any kind of actual proof that somebody was gay, they would be subject to “crimes against nature” or “contributing to the delinquency of a minor,” “homosexual tendencies,” even the wrong clothes. You had to have three articles of women’s clothing on if you were a woman, and three articles of men’s clothing on if you were a man. This was required by law. Otherwise, you could be arrested and charged with cross-dressing.

RN: You were how old?

MM: I was fifteen, sixteen, and then seventeen. We had a gay crowd in high school. Some of the kids had discovered 21st Street Beach, which was the gay beach. They were going to the gay beach. Two of the high school women decided to see if they could get as much of a thrill together as a girl and a guy, deciding that it was better with two girls. A lot of the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth graders were coming out. There was just this whole, big community.

There was a motel, apartments maybe, like condominiums today. It was a set of apartments in Miami where a lot of gay adults lived. There were two couples that would let some of the gay teenagers use their bedroom for trysting because if you were fourteen and fifteen, living at home with your parents, you couldn’t have a same sex lover. Teenagers would go to those apartments, which was very brave of those two couples who hosted them. They really could have been in big, deep doo-doo if they had ever gotten caught.

College Years, Summer Camp, and More on the Johns Committee

RN: You went to the University of Florida in Gainesville, and ran afoul of the infamous Johns Committee.

MM: Yes, that was where that happened. The first year I just kind of did regular college things, and would keep up with my women friends from high school, who were still being gay. I think it was that summer, at summer camp, when a whole bunch of us who knew each other from way back, when we realized that we were gay.

That’s how we had a gay summer at summer camp. Our head counselor was a dyke, a local woman from North Carolina. I remember my buddy Joycie said, “Did you see the head counselor?” Oh, my god, she was gorgeous. And then, my other friend came running in and said, “Did you see the camp doctor?” It was a woman, and she was also dyke. We had an unspoken communication. It was dangerous to be outed, because you could be arrested, lose your job, lose your family, lose everything. We all had a tacit understanding among those of us who were counselors, by then, and the head counselor and the camp doctor.

RN: What was the camp?

MM: Camp Sky Top. It was outside of Rosman, near Brevard, North Carolina. There are a whole bunch of summer camps there. We went out on the camp train every summer with these other camps. One of the camps was run by two women, who, I found out later, of course, were lesbians. There were lots of little dykey girls going to that camp. It was a girls’ camp. My camp was a co-ed camp. And then there was Blue Star, which was the snotty Jewish camp where the rich kids went.

RN: North Carolina is quite a hike from Miami Beach. And you went by train.

MM: We went on the train, and it was an overnight train trip. It was great. It was a camp train! We walked through the train, talking to everybody, meeting everybody. And we ate. It was like a great big party.

RN: I think of summer camp as being something rich kids do. You said you weren’t a rich kid.

MM: No, this was not a rich kid camp. They had camp scholarships, too. There were kids that went there gratis. We got a special rate because me, my brothers, my sister, and my cousins all went. That was a big family, and we got a cut rate. My grandfather sent us. He was the one that was “the money man” who sent us to summer camp. And he sent us to college, and all that.

RN: Well, let’s go back to college. Tell about how you went and how you left the University of Florida.

MM: I was at this apartment place I mentioned earlier, with a couple of friends of mine who wanted to get it on when I came out. Then, I met Penny, who had a huge reputation on the beach as being the woman who brought everybody out, and she had notches on her bedpost. [Laughter]

My friends told me that I had to meet Penny because Penny was brilliant, and Penny was cute, and Penny was just this shining star among all of the young gay kids, which we were. While I was waiting for my friends to finish up their business in the bedroom, here came Penny into the apartment to visit. Yes, this cute little thing walked in, and she said, “Hi, I’m Penny!” and I thought, “You’re Penny?” And it was true! She was all that everyone had said about her. She must have been about eighteen.

We were sixteen, seventeen, eighteen-year-old kids.

What did we know about politics and legislation? Nothing.

But we heard through the grapevine that they were coming

and they were going to get rid of the gays.

We ended up riding home with my friends in their convertible. We stopped and got a bottle of Southern Comfort [a whiskey liqueur]. We passed the bottle around the car. Penny and I got very, very friendly, and we really, really liked each other a lot. She was going back to FSU in Tallahassee, and I was going to Gainesville. [At that time, Merril’s group thought Florida State University was more redneck than the University of Florida. Others considered FSU much more liberal than UF.]

Penny and I wrote letters, and maybe we had a phone call or two. It was in the primitive days of communication when people really communicated directly with each other, not with electronics in between.

I said she should come and visit me sometime. One night, I walked out of my room and she was coming up the hall in my dorm! I thought, oh, my god, people are going to look at her and they’re going to know. I hustled her out of there, and we got a motel room. We spent a couple of days and the night in between in the motel room, which was very nice. Then, she went back to Tallahassee, and I went back to my school. And here came the Johns Committee, which we had known about. It had been rumored in our circles that there was a legislator who was busy busting gay guys and gay women.

RN: And gay professors.

MM: We didn’t have to worry right away because it was mostly the adults they wanted, and they wanted to get the professors out of the universities. Then we heard that they were coming, and they were coming for all of us, so we were pretty terrified because we didn’t have resources, information resources, you know. We were sixteen, seventeen, eighteen-year-old kids. What did we know about politics and legislation? Nothing. But we heard through the grapevine that they were coming and they were going to get rid of the gays. Already, professors had been called in, interrogated, and fired. Other professors had left because they either were worried that they were going to get fired, or they didn’t like what was going on. They had a protest and they got out of there.

At Florida State University, Penny was called in to see the Dean of Women for being so obvious. The Dean of Women said that Penny couldn’t stay in school any longer because she posed too much of a threat to the women in her dormitory. Penny had a petition signed by all the women in her dorm saying that she had never tried to touch any of them. The Dean of Women (who also was a dyke), said, “So sorry, but we will allow you to transfer to the University at Miami because you’re such a brilliant student.” Which she was.

Penny transferred to the University of Miami, and she was not permitted to live in the dormitories. She had to get a solo apartment in student housing. Then, she got involved with thespians who were doing a production of Lysistrata. She had two gay guys that were in the play with her, and they were rehearsing at her apartment. It got late, and they were tired, and she said, “Why don’t you crash here tonight? I’ve got plenty of room. You can go back to school in the morning.” And they did. The next day, a woman who lived down the hall reported Penny for having men in her room. Penny got kicked out of school for having men in her room because that was also against the rules at the universities. You could not have men in your room. There was no co-ed housing then.

We also had to wear dresses. Women were not allowed to wear pants, not allowed to wear shorts. There were all these behavior and dress codes that we women were supposed to follow. I don’t think the boys had any.

RN: You wound up at the University of Miami, too, after Penny had left.

MM: Yes, it was after Penny had left. At the University of Florida, I was called down to the basement by this fellow who identified himself as a campus police officer. He started grilling me about my sign-out card, because I had been going to Tampa to the gay bars. I liked going to the gay bars. There were a couple of women in the dorm who had loaned me and my buddy their IDs so we could get into the bars. Once you got in one time on a fake ID, you were in. You didn’t have to carry it forever. They didn’t card you every time you went in. And we went down a lot.

RN: Those were two hours from Gainesville.

MM: Thereabouts. We took the bus. We went on the Greyhound. Neither of us had a car.

RN: You and who?

MM: My friend Sue. She was my best friend since I was four years old.

RN: You went to college together.

MM: Sue was one of the women that came out at that summer camp. We went to separate high schools, but we went to the same university. She came out in high school with my friend Joycie, who was her best friend at the time. The two of them were like awkward, handholding, best friends who finally went as far as kissing, and finally, went farther than that. They became a brief couple until Joycie got a “wandering eye” for other women.

Sue and I used to go together to the bars in Tampa. When the Johns Committee officer called me in, he must have checked my sign-out card where I wrote down “hotel” or “motel” in Tampa. I wasn’t going to put exactly where I was staying because it was with lesbians. I was seventeen, and the officer wanted to know where I got the money to do all this. He was really pretty ugly. I started crying, and I told him I had a boyfriend, and my boyfriend and I went down to Tampa because I was underage, and because we couldn’t be seen in town, and that I didn’t want to get him in trouble, and that we loved each other so much, and that it was the only place we could go where we could be alone. I said that I had friends in Tampa. I said that we stayed with them, and they let us stay with them even though I was underage because they knew how much my boyfriend and I loved each other, and they wanted to help.

He wanted their names, he wanted to know who they were, and where they lived. I said I couldn’t tell him. Finally, I said that they’re homosexual, and that I couldn’t tell him because it would get them into trouble. He got very quiet, and he said, “Oh, you know the homos here on campus, maybe?”

I thought, “Oh. my god, what have I done?” He believed my boyfriend story, and that was wonderful. I told him, “No, I didn’t know any of the homos on campus. I don’t hang out with homos. It’s just that these people were being so nice to me and my boyfriend because they knew how much we loved each other.

He said, “Well, maybe if they trust you, you could find out who they are, huh?” I thought, “Oh shit, this guy is a sleazy son of a bitch.” I told him to let me think about it, because it was close to the end of the semester. He said snidely, “Well, you go back and you think about it, little lady.” Little lady, god. “You think about it real, real hard.”

I went back and thought about how I could get out of there by transfering to the University of Miami where there was no Johns Committee investigation. What could I tell my mother? Tuition was so cheap at the University of Florida at $75 a semester. The University of Miami was $500 something. That was a lot of money in those days. I don’t remember how I convinced her, but I did convince her. And I transferred to the University of Miami. It was the second half of my sophomore year.

RN: The University of Miami is a private university, which is why it cost more.

MM: Yes, and they would not let the Johns Committee people come to investigate. They said “No!” However, the people that ran the University of Florida, a public university, were more than happy to help the Johns Committee in any way they possibly could. It was really, really horrible. They also went after the schoolteachers in the public school system after they got done with the universities. They got some elementary school teachers, too. Some of the teachers quit, and some of them killed themselves. It was a terrible time. And some of the teachers held their breath, and they just went on the way they went on.

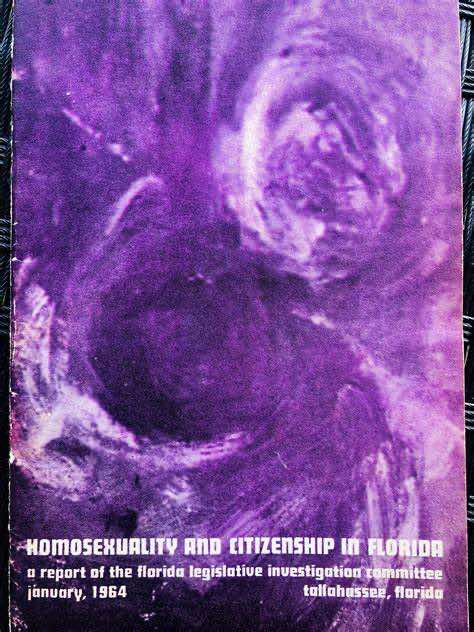

The Johns Committee continued with their investigation for ten years. They raided the bars, and they raided the beaches. They put out this brochure called the Purple Pamphlet, because the cover of it was purple. You can probably look it up now and see it. It was horrible. It was like gay male porn. It was “what to do about the homosexual menace,” and how to deal with this “problem” that we’re having. I thought, “I bet those state legislators are looking at it in their bathrooms and having a good time with it.” At the taxpayer’s expense, they printed it, and they distributed it. Most of the legislators were really, really turned off by it. But the Johns Committee investigation went on and on until, in ten years, the funding was finally cut. Everything disappeared, and went away except for the people whose lives were ruined.

Alabama Years: The First Gay Mixed Marriage

RN: When did you graduate from the University of Miami?

MM: 1962.

RN: How old were you that year?

MM: I was twenty. I had started university early, when I was sixteen.

RN: You landed in rural middle Tennessee for the last forty years.

MM: Almost fifty years.

RN: Almost fifty years! Can you briefly sketch your trajectory between university and moving to Tennessee?

MM: What had been going on in Florida at the time was this. A lot of the gay guys and the gay women were getting married. There were a lot of “mixed” marriages at the time. They did it for safety, for family, and for citizenship because a lot of Cubans were starting to come in. We sort of coupled off, mixed sex with people that were our friends. It was common.

My friend Sue had gotten married to another nice Jewish boy, and one day my mother said, “Everybody is saying how surprised they are that Sue got married. They thought she was a lesbian.” And she looked at me with tears in her eyes, and said, “I wonder what people are saying about you?” Right then, I decided I would marry Jack.

I got married to Jack because he worked for the government, and he needed a wife for a cover. I needed a husband for a cover because my mother was very unhappy about what people thought of me even though she knew I was a lesbian. Jack was a nice Jewish boy, and I liked his family a whole lot.

I was in Alabama with Jack for almost a year, during the time of the Freedom Riders. It got me acquainted

with racism, and with what was going on with integration besides Brown versus Board of Education.

Jack got placed in Gadsden, Alabama, when he got out of his training. Gadsden was his first job site. I went up to visit him in Gadsden during the university holiday of my senior year. We got married, and got it over with. Then, my mom said that since we eloped, she’d buy me a car with the money she would have spent for a wedding. I thought that was a great idea. Then, I came back to finish university.

After I graduated, I went to Gadsden, where my husband was. He was slated to be transferred to Baltimore, but that was the time that President Kennedy put a freeze on government hiring. There was no transfer to Baltimore.

I was in Gadsden with Jack for almost a year, during the time of the Freedom Riders. It got me acquainted with racism, and with what was going on with integration besides Brown versus Board of Education. There were maybe forty Jews in the town, but still, we had a synagogue, we had a rabbi, and we had a Sisterhood. Several of the Sisterhood women were involved in civil rights activism. They would go with African American women to register to vote, and to go to the library to get library cards. We did this and other integration types of behavior and activities. I remember when the Freedom Bus came through on its way to Anniston, Alabama.

RN: Where it was burned?

MM: Where it was turned over, and burned. The bus had gotten a police escort from city limits through Gadsden to the city limits, and they were not allowed to stop in Gadsden.

I was working with some friends, and one day Jack said to me, “Want to go to New York?” He had suddenly gotten transferred to New York City, which was fabulous! I had visited New York only one time. My friend Sue, my best friend from the bar scene, was living in New York City with the gay guy that she married. I really liked the city. I really wanted to live there and be a starving writer in a garret in Greenwich Village where everything was romantic and different, like the places that I’d only read about. The summer that I spent up there with Sue was fun, and I really liked the bars, where the police didn’t come in and arrest people. Sometimes, the police came in and closed a bar, but they never arrested anybody there. Jack and I went to New York City, and that’s how I got to New York.

New York City Years: Teaching in Harlem, and Early Antiwar Activism

RN: What year would that be?

MM: It was the summer of 1963. I got a job for the school year that was coming up.

RN: What was your degree from college?

MM: Education. What else? I was a woman. It could be education or it could be nursing, and that was that. Those were the only careers for women then.

RN: Elementary education, or just education?

MM: Elementary education. When I was young, I wanted to be a veterinarian, and I was told that women could not be veterinarians. I was not interested in getting an Mrs. degree like most of the girls. Instead, I got an education degree.

[An “Mrs.” degree is a slang term in America for a woman who attends college or university with the sole intention of finding a potential spouse in order to become Mrs. so-and-so.]

RN: Where was this teaching job in New York City?

MM: It was in Harlem. It was Central Harlem, and I immediately got the job. I went down for the interview, and they needed teachers. They were desperate, with the school year starting in two weeks. I was hired to teach fifth grade.

I was interviewed along with a woman that I met during the interview, who was hired to teach sixth grade. She was an older woman, around 35 years old. After our first day of school, the two of us went to the bar around the corner, and we drank and drank. Because it was unbelievable. I had to learn a whole new way of teaching. This was not Miami Beach schools. And I loved it.

RN: Were the Harlem schools all Black?

MM: No. There was one Chinese family, who ran the cleaners, the laundry. There was also one Puerto Rican family. It was 122nd Street, between Lenox Avenue and 7th Avenue, and it was a special service school, which meant that they got extra money. It was run by a principal, and two assistant principals, the three of whom were radical, socialist type women who were amazing. They were, the three of them, absolutely dedicated to having as nonracist an environment as possible in the 1960s in an all-Black school, and to making sure that the kids got educated. They made sure the kids were all taught that they could do anything in life they wanted. They didn’t have to be victimized. It was a good environment for this little Florida lesbian.

I was working with runaways, trying to convince them not to be trafficked,

which was happening to a lot of those kids.I’d say, “Hey, call your mother and tell her you’re still alive.”

RN: How long were you in New York City?

MM: I was in New York for almost ten years. I taught for five years in Harlem, and then wanted a change of pace. Jack and I were no longer an item. He went his way, and I went my way. John was already in New York City. Jack and John and I had all been friends in Florida at the University of Miami, and we all knew each other. When Jack and I went to New York City, Jack and John got together as friends. I was living with a woman at the time.

RN: You were living in the Village and teaching in Harlem.

MM: It’s just a short ride by subway. When I was living in Queens with Jack, that was a longer subway ride. When I moved in with Lori, it was in the West Village. First, we lived in a sublet apartment because she was planning to leave her husband. John would date Lori for appearances—when he needed appearances. She was a model, very lovely to look at.

It was funny, because when I lived in Gadsden, Alabama, I watched a program on television called “The Nurses,” with Zena Bethune. I had a crush on one of the nurses in the program, the one with the long hair and the big eyes. When I got to New York, suddenly, there she was at a party, and the actress was Lori. We moved in together, and I thought, “Oh, that’s nice!”

RN: What did you do after you stopped teaching in Harlem?

MM: My best friend Vicky, and John and I opened a head shop in the East Village. We didn’t sell commercially made items. We sold handmade crafts by people in the neighborhood, and we took stuff on consignment. We had four rooms that we got because a fellow we knew, a sculptor, was vacating the property. It was the mid-sixties, and we opened the store. We called it Paranoia.

We had the front room where we had displays of items for sale, and we had a room behind that that was a kitchen where we had free food, grain and vegetable stews for anybody off the street who wanted to eat. We were also somewhat involved in working with street kids, the runaway kids, and I cooked up big dinners every night there.

We had a third room that was decorated in Day-Glo. We had a fourth room in the back where, for a while, we had free clothing give-away, and free household items. The neighborhood teenagers started using it as a make-out room. A friend of ours who was a botanist wanted to turn the fourth room into an Everglades-type environment. He brought in a whole bunch of cattails and also put all kinds of plants around. He got a parrot, and he put the parrot in there. It was really nice until the cattails went to seed, and we had like a foot and a half of fluff all over the floor. It caught fire, and we closed it off.

RN: Oh, no! Where was your store, Paranoia?

MM: It was on 10th Street between 1st Avenue and 2nd Avenue. I was working with street kids who had run away from home, trying to convince them not to be trafficked, which was happening to a lot of them. I’d say, “Hey, call your mother and tell her you’re still alive.”

One night, the police came to my place, a tiny, tiny apartment, looking for a couple of young women that had run away. I knew who they were looking for, and I knew where they were. They were in New Jersey with these boys they were seeing. The cops looked around. I had “two” rooms that were really only one room. I told them that I was working with the kids to try to keep them safe and healthy, as much as possible, being on the streets like that. They said that I’d better not be doing that because I could get in trouble. I could get arrested if anybody’s parents wanted to file charges against me. They scared me enough that I stopped doing that.

We were part of the First International Psychedelic Exposition, which was at Forest Hills Country Club.

That was kind of like an Indian Village for tourists, only we were hippies demonstrating the hippie life style.

RN: Would you call this early activism?

MM: We were working with the guys who wanted to get out of the draft, young guys who didn’t want to go to Canada, and couldn’t really claim conscientious objector status because they didn’t have the papers. We coached them on how to say they were gay and to be convincing. Back then, they didn’t allow gays to be in the military. We told these guys not to be flamboyant, not to dress up, and not to put on airs. They should go in very calmly, and ask to see the psychiatrist or the psychologist. They would tell the psychologist that they were homosexual, and how this would not work well for them to go into the service where there was all this temptation. If these guys were willing to take a classification of 4-F exemption, they could get out of the service that way.

I guess that antiwar movement work was early activism. I was also a member of Another Mother for Peace, though I did not have a child in my mind then. We worked with the guys on getting out of the draft, out of the service. And we went on the first Peace March, which was really, really neat.

When we had the store, we were involved with the psychedelic craftspeople. There were overlapping circles of people. We were part of the First International Psychedelic Exposition, which was at Forest Hills Country Club. That was kind of like an Indian Village for tourists, only we were hippies demonstrating the hippie life style, making crafts and selling our crafts.

That was really when I got the idea of leaving the city, going “back to the land,” and living in the country. People everywhere were talking about the “Tune in, turn on, drop out” phrase, only we were saying, “Tune in, turn on, make change.” We were into the “make change” part of it, from the inside and especially on the outside.

RN: Making change is your activist conscience.

MM: Yes, and more in an environmental way than a feminist way. Even though we hung out mostly with gay guys and lesbians, we also hung out with a lot of straight people. When I got involved with the downtown theatre, the off-off-Broadway theatre scene, it was also largely gay.

I hung out at the Caffe Cino, which was a theatre and coffee house on Cornelia Street that was run by this guy Joe Cino, who was gay. That’s where I met Robert Patrick. I used to go there with Vicky a lot. They had wonderful shows, and many of the folks were gay.

I first got involved with the theatre group that my friend Vicky was involved with, and I wrote a play. It was a play called Quad, which despite its name, turned out in real life to be only three elements because I never got the film part of it, the fourth part, done. They put the play on at the Café La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in New York City, in the old building where La MaMa had started. Ellen Stuart, who started La MaMa, was still there.

We also had a communal house that a bunch of us rented in Tivoli, New York, a couple of hours out of the city. It was across from the Catholic Worker farm, started by Dorothy Day. Every so often, we’d go to hear Dorothy speak there. Most of us circulated in and out of Tivoli House, and we didn’t live there full time. But my politics were enhanced, and I developed a taste for collective living from my years there.

RN: Tennessee was the end of your “back to the land” journey. When did you decide to marry John?

MM: Some time around the late ‘60s, when John and I were tripping [on LSD] together. I had taken LSD with my friend Rachel, who was part of the Tim Leary group, the Millbrook group. Of course, then, I had to share it and to “turn on” [with LSD] my friends. John and I were friends. (Not with Jack. Jack was very, very square.)

RN: Was Jack still around?

MM: Yes, but we weren’t living together. I’d see Jack every once in a while. I’d check in with him to see what was going on, you know, and go out with him if he needed a front for something to do with work or anything. But we had very different circles of friends.

On the other hand, John and I were involved with many other people our age. We were a very tight group. We did a lot of tripping on “acid” [LSD]. It was very profound. We had life-changing experiences. We usually took three days to do a session: a day to get primed for it, a day to actually do it, and then a day to follow up, processing with the group.

RN: You’ve written about this. I’ve heard you read some of it.

MM: Yes, I have a whole collection of early acid stories. Only one has ever been published in a mainstream place, and that was just the very, very beginning of the stories. It was in Girlfriends magazine a long time ago. There may have been another one in Girlfriends another time a while ago too, but I don’t remember. All that was burned up when my house burned.

RN: What is Girlfriends magazine?

MM: It was a women’s magazine, maybe an early, feminist-type magazine. They had all kinds of really good articles.

RN: But not a gay magazine?

MM: No, not gay. I mean they ran gay stuff in there every now and again, but it wasn’t necessarily a gay magazine. They paid me. I always like when that happens.

RN: Back to you and John tripping.

MM: John and I were tripping, and John and I were getting more involved with what we wanted as a future. I went back to graduate school, and it was a turning point. After Harlem, and after the store, I was motorcycle delivery gal for a while, the job with Coleman Younger.

I had a little motorcycle, then a bigger one, and then a third one, even bigger. A friend of mine came in one day, saying that he was doing deliveries for a motorcycle delivery agency. He was making a whole lot of money riding his bike all day, having a wonderful time. Right about then, I think, was when the feminist movement in New York was taking root. It was around 1969, I think.

I wasn’t involved with feminists yet because I was doing the bar scene, the downtown theatre scene, and the psychedelic scene. But I knew who these people were. We all kind of lived in the same area, and some of them were dykes who came to the bars. I knew what they were putting out, and I read their material because we had bookstores. There was a lot of good material available from bookstores. Feminism was interesting, and I thought it was good. I was still in touch with Julia Penelope, and Julia was really getting into feminism. Julia Penelope is Penny, formerly known as Penny Stanley.

RN: Explain about Penny becoming Julia.

MM: Penny became Julia because when she became a more prominent academic, and a feminist separatist, she wanted to drop the diminutive. She took her real name, which was Julia Penelope Stanley. She dropped her father’s name, which was the Stanley part, and she became Julia Penelope.

RN: Julia Penelope was a very well-known linguist who wrote many books. She was also an activist.

MM: Yes. Anyway, I went to get a job with the motorcycle company, Coleman Younger, because I had a bike, and I wanted to ride it. I wanted to make money, and I was not in any kind of immediate employment. I told them I wanted to work for them. If they rejected me because I was a woman, I was going to take them to court, and bring a lawsuit. I had it all blocked out in my head. I went in, and I told them I wanted a job, and they gave me my papers to fill out. Just like that, I got the job. I didn’t get to go to court and sue them after all.

RN: Were you the first woman messenger?

MM: I did get to be the first woman motorcycle messenger in New York. It was a real kick! I was a long-haired butch at the time. I wore long hair and neckties. That was the fashion of the day for butches. I had a beautiful motorcycle helmet in psychedelic colors that a friend of mine had painted. I had my little 250 Yamaha to start with, which was adequate. I would go into places, saying, “I am from Coleman Younger,” and they would stare and say, “What? A girl?” It was fun.

I got a couple of other extra gigs from that. One fellow was supposed to pick up a client at the airport in a limo, and he decided it would be fun to have me on the motorcycle instead of the limo to pick up this dude. I borrowed my friend Michelle’s bike, a silver fox cape, and I brushed my hair nicely out over my shoulders. I also put on makeup. When we got to the airport, the fellow got off the plane, looking around for the limo. The dude who paid me $20 to do this (and that was really good money at the time) said, “Oh, here she is!” The guy got on the back of the bike, and the dude said, “Oh, no, no, no. I really have a limo over there.” The guy said, “Oh, no. I’ll ride on the bike.” Then it started to rain, and he wanted to ride on it anyway, and off we went! It was a lot of fun. It was a fun job.

When I got out of graduate school, I got a job teaching in a program for autistic kids, teenagers, and preteens.

When it got too cold to ride the motorcycle in the winter, I got a job driving a taxi, which was interesting. I also have many stories that I got out of that one. My mom was sending my sister to graduate school, and I asked if she would send me to graduate school, too. She said yes.

I enrolled at Bank Street, where I had done some course work when I was teaching in Harlem. I loved it. I loved the way they taught, I loved the school, and I loved the philosophy. I wasn’t sure what kind of graduate degree I wanted. I had done some substitute teaching in New York after the motorcycle and taxi jobs. I substituted in some of the special education classes, and so they told me at Bank Street that they recommended me for special education because I had done that substitute teaching. Also, I was good at it. I went into their Special Education Program. It was a wonderful experience, very heavy on autism and behavior disorders. I got my Masters in education with a major in special teaching.

When I got out of graduate school, I got a job teaching in a program for autistic kids, teenagers, and preteens. I had a student teaching post. I really liked the kids and the work. I had a wonderful directing teacher who taught me a whole lot. I got a job teaching in a hybrid program between the New York City public school system and the Association for Mentally Ill Children, which was a private group. The school system hired the teachers, made sure the teachers had their papers in order, and paid the teachers’ salaries. The Association for Mentally Ill Children hired specialists.

It was such an amazingly excellent program. I had three kids in my class. We were housed at the Boys Club of New York facility. There were three classes, and the other two teachers for the other two classes were gay guys who became very good friends of mine. We had a music therapist, an art therapist, a movement therapist, a dance therapist, and a shop therapist. We had all these extra people that came in, and we had all the facilities at the Boys Club at our disposal, including the swimming pool, the weights room, the boxing room, the gym, and the kitchen. We did everything with those kids.

RN: Was it all boys?

MM: Yes, but it was only all boys because that’s what it was. There were a couple of girls in the younger classes. Autism wasn’t as prominent and predominant as it is now. There were few kids with autism. We also had a couple of kids who were not autistic, and who had mental illness conditions that fit into the class. It was adolescents and pre-adolescents, the program that I taught. Across town, in the church, they housed the lower grades. They had two or three kids in any class.

RN: What grades were you teaching?

MM: It wasn’t graded. Some of the kids were mid-level learners, and others were more primitive. My kids all had language abilities. They all were actually, I would say, “Aspergery” types [Asperger’s syndrome is a kind of autism]. The younger kids in the other classes were less verbal and more active. The most advanced class was my friend Dan’s class, and there were six students. They were very high-achieving kids. I’m sure most of them continued on in school. One of the students is my friend Kevin, who still visits me from New York. He’s in his sixties now.

I taught for the rest of the year, and then we bought Joey Skaggs’ school bus. We hit the road, looking for the hippie, pie-in-the-sky place to buy land, and to do “back to the land.” During that time, John and I decided that we would be a team, and that we wanted to provide a home for kids who were hard to place in adopted homes. I wanted to do a free school. While I was at Bank Street, I got really, really involved in the free school movement.

I got a copy of Raspberry Exercises, which was a book about starting your own school. They had a whole network around the country. They had a publication, This Magazine is About Schools, by and about people who wanted to start their own free school, or their own country school. They were not homeschoolers of the Christian type that you see now so much. They were mostly environmentalists, back to the land people, and a lot of them were hippies. I wanted to start a school, and John was in graduate school studying the intentional community movements. We both wanted to do intentional community.

Second Gay Mixed Marriage and Looking for Land

RN: You drove cross country?

MM: Yes, 14,000 miles. Maybe it was 40,000. I don’t remember. We went down into Florida, up into Canada, across Canada, back down into Mexico, up into San Diego, and across from San Diego. We had planned on settling in New Mexico, where friends from New York had gone. But we didn’t like New Mexico. We thought we would look for land in Arkansas because we knew about Eureka Springs, which was a hippie place. We also considered North Carolina because both of us liked the Blue Ridge Mountains and that whole area, or possibly Kentucky. Oregon was our other consideration. We did not want to get a place in the Southeast because we had a Black child. We remembered the attitudes in the Southeast from the 1950s.

I think it was probably 1966, when we were in New York, and we started our adoption stuff. We had adopted our first child, who was a biracial foundling with no history, and who was, in fact, left at the foundling hospital in New York in a box with some food and clothing. That is very unusual for New York. When I taught in Harlem, my school kids would find babies in paper bags, in garbage cans, and under bushes. I have a friend in New York who was found as a baby in a garbage can and rescued. People weren’t always so kind about leaving their unwanted babies.

John and I had made that decision about adopting already. That’s what we wanted to do. Adoptions to single people were just then being allowed. But my mother said that would be very difficult for us to follow through if we wanted to have any kind of a history.

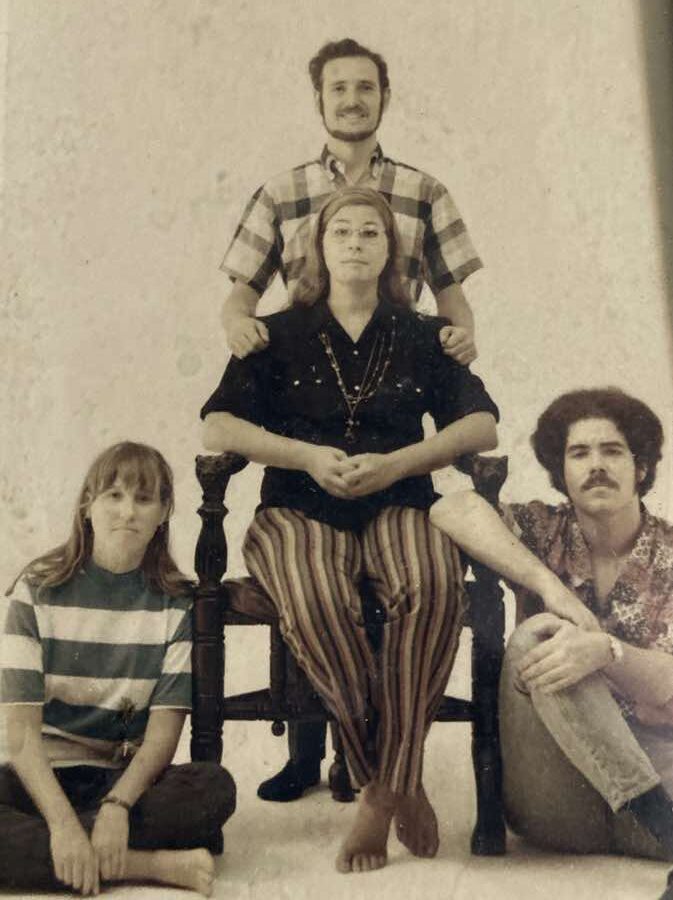

That’s why we got married. We didn’t care. You get married, or you don’t get married. We got married, and after that, we had a big, hippie wedding at a friend’s estate in New Jersey. It was a weekend event with costumes and camping. Our family and friends came, and there were tons and tons of people. We did all our own cooking, and we had a decorate-it-yourself, yin yang wedding cake that people got to play with. It was a really, really fun.

Francis Lee, a fellow who was staying at the house, was a videographer and a film maker. He was a pioneer in photo-animatation, as it turned out. Sharon Thompson researched a lot of his work. [Sharon Thompson and others started the Lesbian Home Movie Project].

RN: Did you lose your copy of that movie?

MM: Yes. Sharon sent me another copy.

RN: Where did she get it?

MM: The movie that Francis did was a 36 mm, a reel to reel. Baba Ram Dass wrote and read the narration for it, as a friend of Francis. Francis got photos from my cousin, and he used those to do his photo-animation. It was a really neat film. He was going to put music to it, but he died before he could compose the music.

Francis Lee was nominated for an Academy Award for a documentary that he did. It was a World War II documentary, narrated by Marlene Dietrich about the rise of Hitler, called The Black Fox. We got a copy and watched it back in the early computer days.

I met Sharon Thompson at an OLOC [Old Lesbians Organizing for Change] conference. She was talking about the Lesbian Home Movie Project. The film that we had already was getting kind of old, and losing its color. I asked her if she would possibly be interested in something like that. It wasn’t necessarily a lesbian movie, but it was a gay and lesbian wedding, a hippie wedding. She said yes, she was interested, and I sent her the film. She now has the film in her preservation area. She got it professionally digitized, and she sent me the digital copy. She showed it at the New York MIX Festival. [The Lesbian Home Movie Project is now part of the Harvard Film Archive.]

Lesbians Led Us to Knoxville, Tennessee

RN: Tell how you wound up in Tennessee.

MM: We wound up here because we didn’t like New Mexico. It was too dry. Arkansas was too far away from everything. The Great Smoky Mountains were too expensive. We were committed to living anywhere but the Southeast because of what went on in the 1950s and 1960s with civil rights. Our first child was Black. When we were in New Mexico, we had to make a decision. We thought that if we went to Oregon, and we didn’t like it, then we’d be stuck. Earlier, we had stopped by to see Julia Penelope, who was by then in Athens, Georgia, teaching at the University of Georgia there. She had gone through several other states after she left New York, and she had finally finished university. I think she may have finished in New York, in linguistics. She moved out to Lincoln, Nebraska, and started the Lincoln Legion of Lesbians out there. Now, she was in Athens, Georgia.

[Wikipedia says that Julia finished at City College of New York in English and linguistics in 1966, then got a PhD in English at the University of Texas in Austin in 1971. Wikipedia also says that she was expelled from Florida State University by the Johns Committee. This is incorrect. She was not expelled by the Johns Committee. Merril went through that experience with Julia when the FSU dean expelled her for being “so obvious” a lesbian, and because she “posed too much of a threat to the women in her dormitory.”]

Anyway, we stopped and saw Julia in Athens. She wanted to do the intentional land community with us. She was very involved with the idea, and with the planning to get back-to-the-land, and all that. And psychedelics. We had done a lot of acid in New York with her.

We told Julia where we were looking to settle, and how we were not looking in the Southeast and why. By now, it was the beginning of the 1970s, and she said, “It’s different now in the Southeast than it was in the 1950s. Things have eased up a lot. Racism is always an issue, of course, everywhere in the country—not just in the Southeast. It’s not as blatant, and there are not cross-burnings as there used to be. The Klan [white nationalist domestic terrorist group, the Ku Klux Klan] doesn’t ride through the night on their horses the way they used to.”

We landed in Knoxville because the lesbians were in Knoxville. That’s when I got really involved in feminism.

When we ran out of money again, we had to stop somewhere. I got back in touch with Julia, who knew lesbians in Knoxville, Tennessee. We thought Knoxville would be a good place because we could be in the Smokies there, and we could look for a place in Kentucky from Knoxville. We even considered looking in North Georgia as a possibility, and Knoxville was pretty central. We landed in Knoxville because the lesbians were in Knoxville.

RN: Is this when you got more focused on feminism?

MM: Feminist activism, yes. The group of lesbians that we knew were mostly university students from the University of Tennessee. You know, UT is in Knoxville. Some of them were “out in the world,” such as some blue-collar folks.

They started a consciousness-raising group. “Oh, let’s have a consciousness-raising group, that’s a good idea! The feminists are doing this now.” Our consciousness-raising group was really, really interesting. Also, we did a lot of reading, had a lot of speakers, and there were all of these lesbian/gay conferences going on.

There was the Gay Academic Union Conference in New York, which I went to for a couple of years, and which Julia Penelope was also very involved in setting up. She made them acknowledge the lesbians. They didn’t have a room set up for the lesbians to meet. It was all geared toward the men, who were the “important” homosexuals of the time. I also went to a conference in Memphis for organizing Southern gay guys and lesbians in the area.

Lesbians were having a hard time then. We weren’t allowed at the Women’s Center in Knoxville, either. Unbeknownst to the administration, two of their employees were dykes, and a woman serving on their board was a dyke. Those women just let us have our lesbian meetings there unofficially, and they never said anything to the bigots. That was great!

RN: There were several lesbian and gay conferences in Atlanta.

MM: Yes, there were quite a few in Atlanta. I got involved with Charis [Charis Books and More] and with ALFA [the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance]. There was that big conference that they had in Athens, Georgia, that I wrote about for Sinister Wisdom.

When the AAUW [American Association of University Women] folks from the university had a big, well-funded conference, it was so unfeminist and so unfriendly to lesbians. Julia and some of her cohorts approached them and said, “Look, this is a women’s conference. Why is your workshop on female sexuality led by a man? You have no scholarships and no childcare. It’s very expensive. There’s nothing on the agenda about lesbians, or women in prison, or women on welfare.” The AAUW women were not receptive, so Julia and company put on an alternative conference across the street, free, with all the things that the other conference lacked.

Gloria Steinem, who was the AAUW’s paid keynote speaker, did something extraordinary. Gloria Steinem went across the street and spoke at the alternative conference—for free! A lot of the AAUW folks crossed the street to attend our sessions.

That’s how we got involved with Sinister Wisdom. I had met Ann there and got to be friends. She told me about friends of hers, Catherine Nicolson and Harriet Desmoines, who were thinking about starting a magazine. They visited us in Knoxville, and we encouraged them to start the magazine that became Sinister Wisdom. [See “The Great Conference Caper and the Beginning of Sinister Wisdom,” Sinister Wisdom 70 (2007)].

The Sunshine Center and Confessions Magazines

RN: You’re in Knoxville, looking for land, and now you’re connected with the lesbians. Talk about how the Sinister Wisdom editors came to talk to your group in Knoxville.

MM: I wrote about that in “Dykes to the Rescue!” [Sinister Wisdom 93, 2014]

RN: You also wrote about Belly Acres in Sinister Wisdom volume 98, Landykes of the South. What did land mean to you? How did you decide to find some land?

MM: In New York, I fell in love with communal living when I was part of the Tivoli House. And that Psychedelic Expo in Forest Hills had set my intention of going back to the land. I was getting radicalized now in Knoxville.

I was working at the Sunshine Center in Knoxville, and I was getting radicalized by the people I worked with.

RN: Weren’t you radicalized in New York?

MM: I was radicalized taking psychedelic drugs! [Laughter] And by writing a play, going to Caffé Cino, going to the gay bars, and seeing if I could make my way through every woman in New York before I left. I was busy. I had a job, too, a full-time job. I was doing antiwar and antiracism work. Feminist activism was one more thing that I could read about and hear about and be glad it was happening. But at first, it didn’t grab me to where I wanted to let go of anything else I was doing to make time to do it.

I didn’t really see the purpose of it at that point. Women were going to the Stonewall Inn, good. Not me. I’m doing something else. We had a lot of feminism at the gay conferences I attended, and at the Gay Academic Union. I learned what I learned, and then I took it back with me, and made it part of my life. I didn’t have to be in that group of people in order to get the effectiveness of what they were doing. I didn’t see how to apply it to my life in general. There just wasn’t enough time to do everything.

Now I’m in Knoxville, and I’m NOT doing theatre, and I’m not doing downtown, and I’m not doing LSD anymore. I’m not doing any of that stuff. The group that I was with wanted to do a consciousness-raising group because that was what we were learning to do from the New York feminists and the California feminists. We did it our way, not their way, because we were Southern women, and Southern women do things differently. We were nicer to each other.

I was working at the Sunshine Center in Knoxville, and I was getting radicalized by the people I worked with. There was one particular incident that happened. There was a woman who drove the van to pick up the kids that came to the place. She had a bunch of kids of her own. I saw her husband at one point and really disliked him. One day she got hold of me in the yard outside one of the buildings, and said, “Merril, how can I get me some of this women’s lib?” I thought, “Ah! I’ll bet she is in an abusive relationship.” These are women that just don’t know how to go about doing anything to free themselves.

I wrote stories for many different true confessions magazines about

women helping women in different situations, one of which was having babies with birth defects.

I didn’t know how to go about doing that much, but that was what got me started writing “true confession” stories for the McFadden Group, which owned the chain of “true confessions” magazines. They paid well for stories. My friend Catherine from Knoxville had bought a new car, and I asked where she got the car. She said, “Oh, I’m writing confession stories!” I said, “Ew! How could you?” She said, “No, they have a new editor, and this editor has a feminist leaning. You ought to get a couple of copies and see the kinds of things they’re printing. It’s not just the ‘My boyfriend left me in high school, poor thing’ stories.” She was writing about recovery because she was in a recovery program. She was writing to women who either had problems with addiction, or who had a mate who had problems with addiction. She told them where to find help, what numbers to call, and how women help each other in circumstances like this.

All that clicked together for me when Janie asked me about getting some of that women’s lib. I wrote stories for many different true confessions magazines about women helping women in different situations, one of which was having babies with birth defects. I was doing a lot of disability advocacy where I worked. There was one editor for all of these magazines who was evidently a feminist. She ran a lot of stories by and about women helping other women in difficult situations. The situations weren’t necessarily real-life situations that were happening to the writer, but they were situations that were happening to women, such as battering.

RN: Where were you working then?

MM: I worked at Sunshine Center, a place that took children and adults that no other program would take, and children that the public schools wouldn’t take. That was before the mandatory education law went into effect. They had multiple handicaps, and most were severely handicapped. The director’s primary area of interest was deaf, mentally retarded, juvenile offenders. The Sunshine Center had a lot of really good programs there. It paid minimum wage, and we worked five days a week, eight hours a day around the calendar. And didn’t get any benefits. Still, it was a really good place to work.

RN: You also went to work at a nuclear power construction site.

MM: Yes, that was when I got out here to the country, and I couldn’t get a teaching job because I wasn’t anybody’s relative or spouse. That’s how they do things out here.

Belly Acres: Rural, Middle Tennessee, and Construction

RN: How did you get to the land?

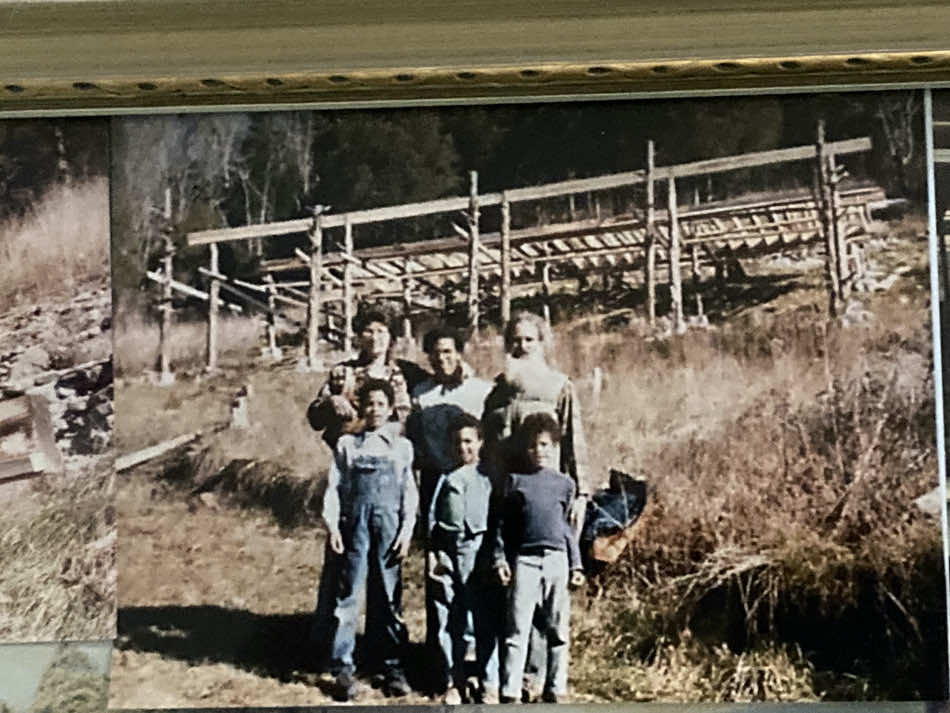

MM: We were in Knoxville, getting a group of people together who were interested in doing a collective. We were doing back-to-the-land stuff and were looking for other people who were interested in the area. One day, my cousin Billy was reading an old Mother Earth News magazine, where there was a letter from people who had relocated from the Northeast, and who had bought land not too far from Knoxville, out in the country. They wrote, “The land is cheap, and the locals are friendly.” We took a ride out to visit them. He was making the tea, and she was cutting the wood. We liked them a lot.

Several months later, in winter, this couple was driving back from visiting family in New England and their car broke down outside of Knoxville. They called us and asked if they could stay with us for a few days while they got their car fixed. It was the two of them with another young man and young woman, who also lived in the area with them. The four of them came and stayed with us, and we just really, really got along with them. They were fun to hang out with. We told them that we were looking for land, and that from the letter they had written in Mother Earth News, it sounded like a good area.

Not too long after that, she called us to say there was a piece of land available down the road near where they lived, and that we should come and have a look at it. We went to look at it, and we bought it, and that was it. We bought the land in maybe 1975 or 1976. That was Belly Acres.

RN: Belly Acres was the land where your house later burned down?

MM: Yes, eventually. At first, there were two old houses on it and two barns. It had six springs, and a creek up the middle, just lots and lots of water. We had a spring that the locals had said was endless. One year, it stopped running and nobody knew why.

RN: How many acres was Belly Acres?

MM: They deeded it as “ninety-nine acres, more or less,” which was good because if it were deeded as a hundred or more, the taxes would be much higher.

RN: Were the structures on the land in good enough condition to live in them?

MM: Yes. We had bought the place, and we went back to Knoxville to keep working to make enough money to pay on it. But we didn’t stay in Knoxville. We moved back out to the land when our money was not stretching that far. It became, “Why are we paying rent and a mortgage?” We had lots of people, mostly women, who came in and out, visiting the land from all different places, I’m glad to say.

Several friends of ours lived in the place, and it was very livable. The back house was going to be the dyke house, women only, with Julia and her lover, and their bunch, whoever came with Julia. The front house was our house, with John, myself, my cousin Billy, and however many kids we were accumulating at the time.

Things kind of shifted around a little, and more kids kept coming. There wasn’t enough room, so we had to build an upstairs. There were only joists up there. There weren’t any floors or walls or anything. We made an upstairs so we could spread out a little bit more. Julia and her girlfriend left because it wasn’t working out for them to stay there.

RN: You mean, the location, or their relationship?

MM: I think all of the above.

RN: And Billy left. You write about this in the story about Belly Acres, “Landyke in a Strange Land” [Sinister Wisdom 98, Landykes of the South]

MM: Yes. Everything now was our responsibility. We had to pay all that rent and we refinanced our seven-year mortgage several times. And you know, it was fine; it was okay. Everything worked. We lived pretty close to the bone for a while, but we had the bones! It was great. There was a very big hippie community here at that time. No gays, lesbians, and queers at the time. Just “us.” We were the only ones. I went away a lot. I went to Atlanta [Georgia] a lot. Womonwrites was happening near Atlanta. Nashville [Tennessee] was close enough, too. The lesbian South was moving and shaking.

RN: This is when you took the job at the nuclear power construction site?

MM: Yes. I couldn’t get any other job locally because it’s who you are and who are your relations, not somebody like me, coming in from outside with a bunch of degrees and accomplishments.

RN: Have you written about working in construction?

MM: Oh yes, in “Walking Steel,” a story that I wrote. I had a book in progress about that experience. But that all burned up [when my house burned], and I didn’t have any backup for the manuscript.

But anyway, I knew a person who was on the TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] board. I knew her quite well, as a matter of fact. It was hard to get on at TVA. She got me the job, and tried to get every lesbian she knew a job with TVA. You really needed to know somebody to get you on at TVA. It was a huge project, a very high-paying job with good benefits, and everybody wanted to work there.

RN: Lenny Lasater talked in her interview about how hard it was to get a job in coal mining. She knew somebody, too. But there were also mandates for women about that.

MM: That’s right, and that helped. At that time, the federal government said that projects receiving federal funding must have a certain percentage of females in the workforce. They had to hire women. It helped to know somebody to put my name in the bin. But they had to hire women. They were really looking to get those statistics up, because that was a matter of federal money grants.

RN: How long did you do that construction work?

MM: A couple of years as a carpenter apprentice. And as a welder after I went to welding school. I did it because it was a job, and because I knew somebody who could get me this job.

RN: There wasn’t any activism in doing that?

MM: No. It was desperation, not activism.

The Adventures of Adopting and Early Advocacy

RN: How many kids did you have by then?

MM: Three or four.

RN: These adoptions as a form of activism seems unusual.

MM: That was, that is, my thing: child advocacy; and child and family advocacy, especially families and children with special needs. I did a lot of disability rights stuff, especially early on. When it’s children with disabilities, then it’s even more my thing. That’s where everything fell into place for me. I was really into it, since the beginning when I was in New York. And everything played out well.

RN: Is that what you and John were planning from the beginning?

MM: We didn’t plan anything about “family.” We just thought about Belly Acres as a place for kids to be where they’d be cared for. Yes, it didn’t have anything to do with family, or marrying, or any kind of that stuff. It was like this: you’re going to plant a garden, you go to get your seeds, put them in the garden, and you work your garden. There’s nothing about being a commercial vegetable producer.

For us, it was what we wanted to do in terms of child advocacy. You know, there are all these kids floating around. They’re in foster care, and they’re on the streets. But there’s not a place for them. I guess that’s how it dovetailed in with my working with the street kids in the mid-sixties, and being a teacher. I took my school kids out on weekends. It was just always that kind of way, and life fell along in line with that.

RN: When you were living in New York City, J’aime just sort of turned up. Were you looking for a baby?

MM: Yes. We had applied with the welfare system to be adoptive parents. At the time, it was called the Department of Human Services (DHS). Now it’s called the Department of Children’s Services. They did food stamps, adoption, and foster care. It was all lumped into one agency in New York. Down here, I guess it would be called Children’s Protective Services. They have Adult Protective Services as well. But it’s all different from the agencies that handle food stamps and disability.

RN: You applied as adoptive parents and not as foster parents?

MM: Yes, as adoptive parents. We wanted hard-to-place children. Hard-to-place would mean, during that period in time: older children, mixed-race children, kids with anything less than 100% use of their body or mind, and sibling sets. All kinds, all kinds. The worker asked what kind of children we thought we could handle, and what kind of children we thought we could not handle.

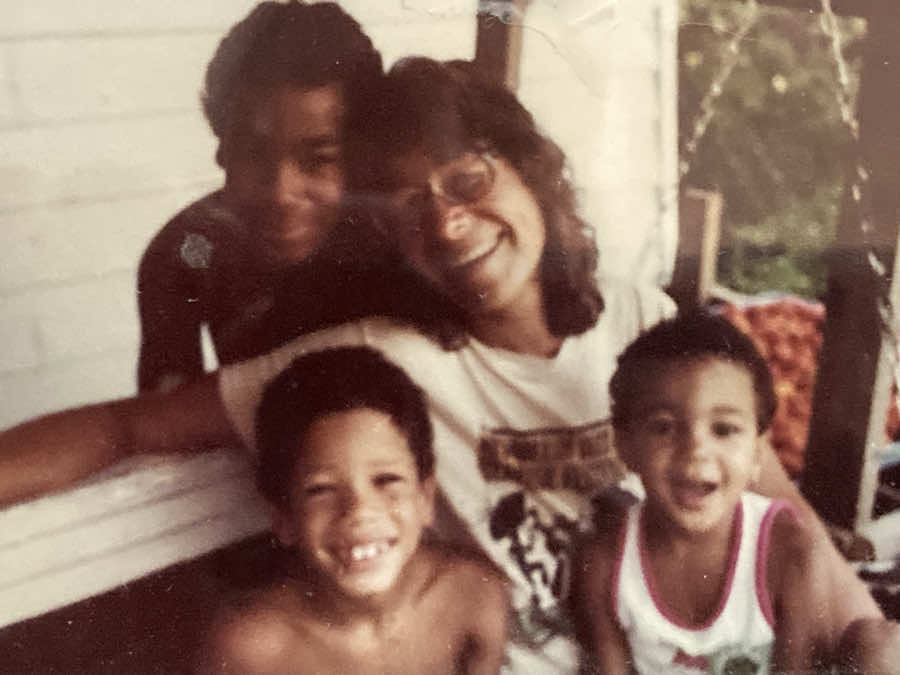

We had a long list of kids that we would be willing to take in. Yes, we would take a baby, but we didn’t insist on a baby. After three months from applying, when the paperwork had gone through, the agency called to ask if we would consider a foundling. I asked what that meant. She said it meant that it was an abandoned baby, with no history, and no medical history. There’s wasn’t anything like DNA testing at the time. We said sure. She said that he was biracial, he seemed to have all of his working parts working, and he was ten weeks old.

We went down to see him and to meet him. The worker was really good. She pushed the baby in a crib into the room where we were. She didn’t hand him to us. She went out of the room and closed the door. I had asked if we could take him out of the crib, and she said yes. She left it up to us to relate with him whatever we wanted, without suddenly having a baby plunked in our lap, which might be upsetting.

He was adorable. Yes, we played with him, and he played with us. We put him back in the crib. The worker came back, and we told her that we loved him, and we would love to make a home for him. She said, “Okay, take him home.” We thought, “Whoops, right now?” [Laughter]

We had to stop and buy diapers, bottles, formula, and whatever you need for a baby, everything, right then, on our way home with him.

RN: You must have taken him across country on that long bus trip.

MM: Oh yes, we had a ball with him. With him and our dog named Found. That’s what the dog was. He had followed me home from the New York streets one day. We figured that he was a stray, and we kept him.

David was Black. That was his “disability.”

RN: How old was J’aime when you moved out to Belly Acres?

MM: He was four, maybe five. It was J’aime, David, and Ananda by then. David came to live with us in Knoxville, and Ananda arrived two weeks before we left Knoxville for Belly Acres.

RN: What was David’s disability?

MM: David was Black. That was his “disability.”

David was in foster care when we had applied. He was with a white foster family, and they thought David was white. He was listed as a healthy, white, 100% American baby, highly adoptable. That was David. Then his foster parents took him to the doctor for his three-month checkup, and the doctor said, “Oh, I see they gave you a Black baby!” And they couldn’t believe it. The doctor assured them that yes, David is Black. That one doctor’s visit changed David’s category to “hard to place” because “suddenly,” he was Black. Being Black changed David to “disabled” and “hard to place.” It was lucky that we had just applied.

RN: Why did they think he was white?

MM: Because he looked white. His hair hadn’t come in yet. He didn’t have a Mongolian spot on his back. That’s a genetic characteristic of Black babies. It’s a bruised-looking place on their back. For some of them, it’s very big, and for others, it’s teeny-tiny. They call it the Mongolian spot, but I don’t know why. It’s a genetic, physical characteristic.

RN: How old was David when you got him?

MM: It took forever for that paperwork to go through. He was nine months old when the paperwork was finally official, and he came to live with us. That was a long, six-month wait.

RN: Why weren’t you interested in foster care?

MM: We got interested in foster care after we adopted. I was interested, but I didn’t want to do it then because I didn’t want to have a child going in and out of a home. I wanted a child to come and stay with. Adoption was always an aim and the goal. Foster care was secondary to that.

RN: You moved out to the country. When did you adopt the other three kids?

MM: Actually, Ananda came to live with us in Knoxville two weeks before we moved to the country. It was a situation where we wanted to do a specific kind of adoption. We really wanted a kid that was very hard to place, like with disabilities or siblings. They have a book in Tennessee called the Tennessee Red Book, which is like a book full of “used children.” It has photos of all of these very hard to place children, along with descriptions and with little bios of all of them. We had been through the “used children” book, and we had made requests for different children from there. I guess they have a book like that in every state.

We had a horrible, horrible case worker who told me one day that he thought he was doing families a favor by not giving a “hard to place” child to them, especially if the child had a disability. I had such strong words with him about that. I told him that it was his job to place children with families.

Talk about feminism and advocacy and radical agitation. I was haranguing him. I would call him in the afternoon every few days, and say to him, “What about this one? What about this one? And what about this one?” We had told him that we wanted a child no younger than two, preferably older. No babies. We were done with having babies. On one of those calls, he said, “Hold on a minute!” He got off the phone and I heard all this buzzing in the background. Then he got back on the phone, and said, “My supervisor wants to know if you would take a normal infant.”

John and I were always in agreement about this: that whatever child came to us would be the child that we were supposed to raise. There was no such thing as turning someone down who was offered. I asked the case worker, “Why is she suddenly available?” Her mother was fourteen, her father was somewhere, who knew where, and she was very evidently mixed-race. Her mother was white, and the baby wasn’t being well cared for. She was covered with a rash, she was underfed, and she was dirty. The workers felt that the mother really didn’t want this baby.

RN: They took the baby away from her?

MM: Yes, it’s a process. They have to. Sometimes, like with Scott, the birth mother has such mixed feelings about keeping her child or letting the child be adopted. There’s a huge amount of guilt, and a huge amount of regret that goes with it. It’s very difficult. The department was not really good about recognizing the difficulty a birth mother has when a child is removed from her home to be placed elsewhere.

Very often, the parents really want to place the child, but they can’t make the decision. Instead, they are non-compliant with their care plan, and that forces the social worker to do it. The social worker will take the child so that the mothers feel less guilt. That may have been what was going on with the mother in this case. I mean, it’s not something you can ask somebody, “Hey, are you doing this on purpose, not caring for your child because you can’t give up your child, but you want someone to take her away?” That’s not something somebody’s going to engage with really well. But sometimes, that is the real reason.

But anyway, here came Ananda, three months old. I wore her in a snuggly carrier against my chest to go to the International Women’s Decade conference in Tennessee. That’s the conference that I wrote about in my story, “Dykes to the Rescue.”

I was going to a lot of different places to be with lesbians, and I was active in all those places. There were a lot of conferences and festivals. I went to Michigan [the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival] a couple of times. I went to Rhythm Fest. I went to all of those great Southern lesbian festivals and feminist festivals. I attended Womonwrites each year for thirty-nine years. And when I wasn’t with the lesbians, I was working on disability advocacy, child advocacy, and family advocacy. I was on a whole shitload of boards and committees. You’ve got to have a big mouth and speak out to get anything done.

RN: Talk about some of the boards where you served, and the advocacy you were doing.

MM: When I moved here, Nashville became my city even though it’s pretty far away. Knoxville was my city when I lived there, of course. I got involved with the disability rights people when I was in Knoxville. I got connected with people from the Tennessee School for the Blind and the School for the Deaf.

At the first conference I attended, I asked why they didn’t have childcare.

I thought, “Oh, my god, this is an activism conference, and you’re not activizing!”

I’d met some people in Nashville who were disability advocates, such as it was in Tennessee at the time. Some parents were calling me because of problems they were having with their school systems that didn’t want to serve certain types of disabilities that their kids had. I was pretty engaged with that because I knew the laws, and I could advise the parents about their rights.

I met other people who were involved with different agencies having to do with disability activism and disability rights, and their programs. There were so few people in the field across the state that we all could fit in a statewide conference. Everybody came from all the different disciplines and all the different age groups. At the first conference I attended, I asked why they didn’t have childcare. I thought, “Oh, my god, this is an activism conference and you’re not activizing!”