Lenny Lasater: Coal Miner, Electrician, Musician, and Renaissance Butch

Interview by Merril Mushroom, April 2, 2024

View part 1 of this Zoom interview on our YouTube channel

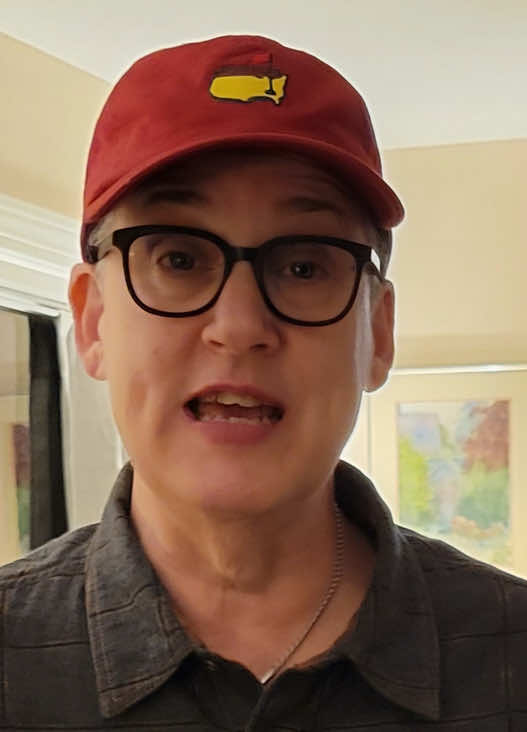

Merril Mushroom: I am here with Lenny Lasater, woman of all trades, woman of vast energy and huge wonderfulness. I am just so pleased to be here. Start with a brief overview of your life.

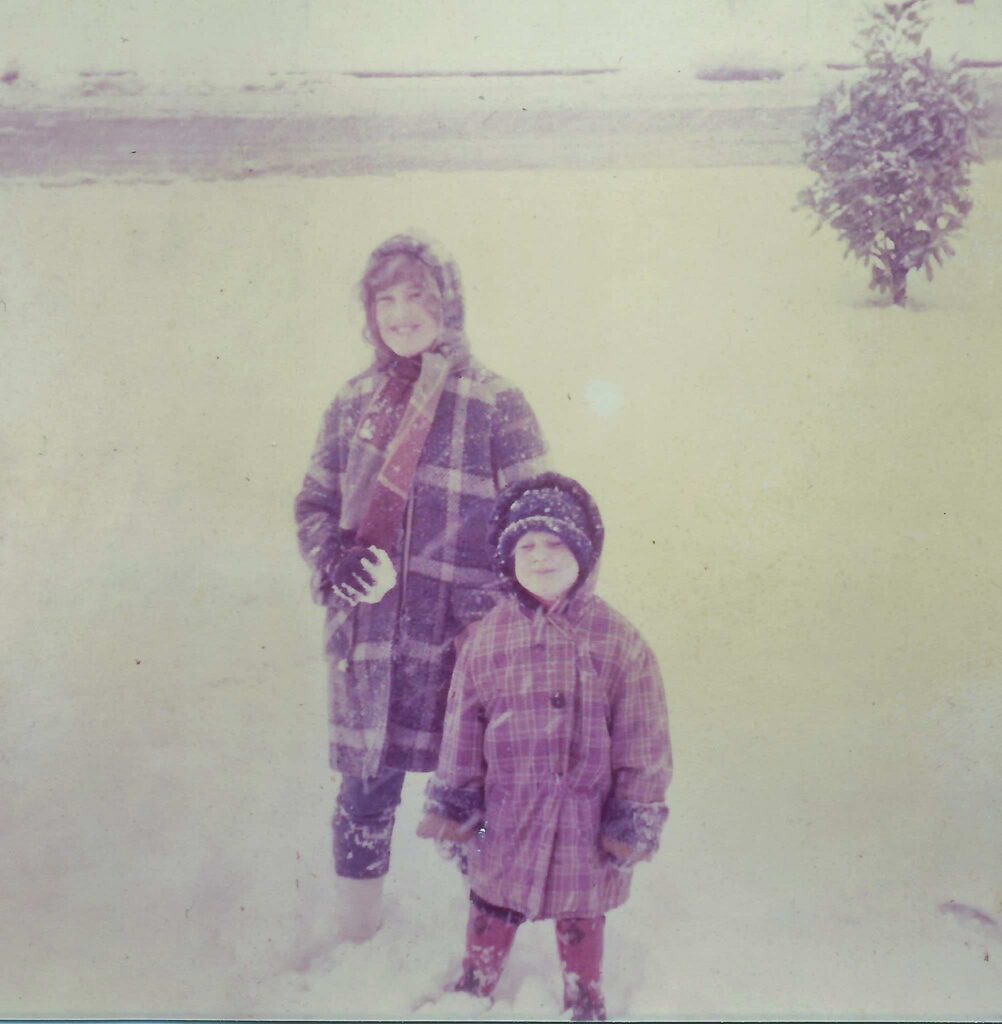

Lenny Lasater: Okay. Hi, I’m Lenny. I was born in 1957. This Friday, April 5, is my birthday. I’m a very butch lesbian. I was born in northwest Tennessee. Tennessee is a long skinny state, so northwest Tennessee is about 110 miles north of Memphis, five miles south of the Kentucky state line, and twenty miles east of the Mississippi River. It’s right up in that corner above Memphis. That’s where I grew up.

I was the older of just two kids. My younger brother was born when I was seven. Mom and Dad were very active at Second Baptist Church. I spent a lot of time there. My father was a church organist. Mom taught Sunday school and played the piano. There was a lot of music in my family and my upbringing: singing, piano lessons, and choir. And the church was big because we were always there. Lots of music. I loved the music and the passion. That would be the thing that caught me. It was in the energy of the music in the church and how music would wash over us.

I did get saved and baptized and all that stuff. I was very young when that happened. I was in the church all the time, and I thought I would die and go to hell if I didn’t get saved. They had indoctrinated me pretty well.

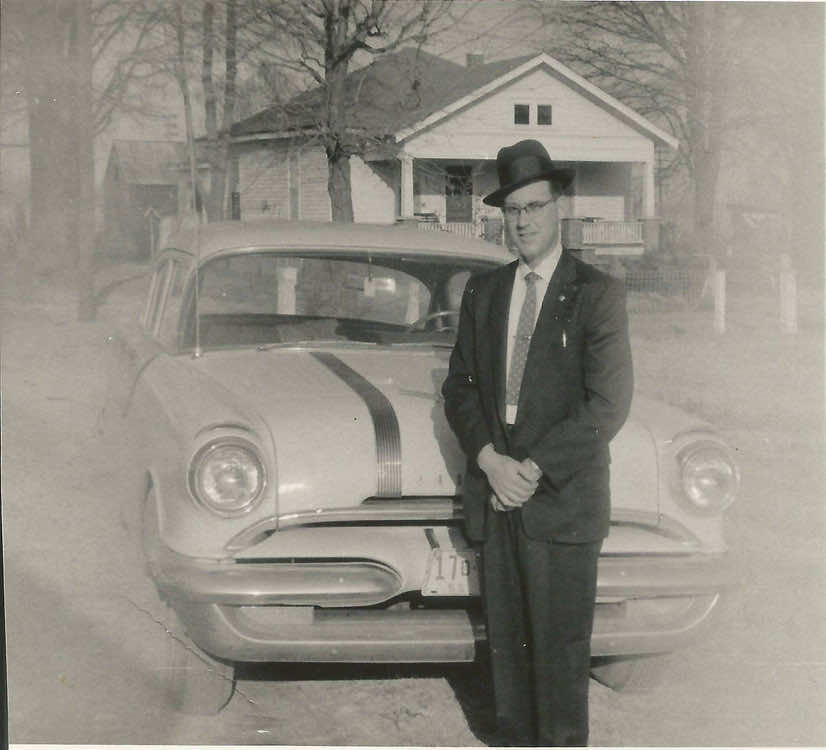

I was not out in high school. I was pretty boy crazy, but mostly because I liked the stuff boys had: their cars, their hobbies, their knives, and their Harley Davidson motorcycles. I liked guy stuff a lot. I had access to guys because I was younger, and I had long hair. I would date guys with hot rods, and I could make them let me drive. [Laughter]

Biographical Note

In the late 1970s, Lenny Lasater was a trailblazer for women when she joined the first class of women coal miners in the United Mine Workers of America local union in Birmingham while working in the deep mines of Alabama. She accomplished this after two years as a psychology major at the University of Tennessee in Martin, and then, a short stint studying pharmacology at Samford University in Birmingham.

Lenny continued on a circuitous path to be only the second woman to reach journeyman level of electricians with the IBEW [International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers] local union in Nashville, Tennessee, which did, indeed, take her on many journeys.

I remember this one guy who had this big, white Chevrolet Impala. The speedometer went all the way to 120 miles an hour. I would lay that speedometer down, baby! This was before seatbelts, and he would sit over there with white knuckles. He said, “If we had a blowout at this speed, it would be a catastrophic event.” I said, “Do you have bad tires?” He said “No.” I said “Well, don’t fucking say that!” [Laughter] “And don’t you ever show up here with bad tires either, mister!”

I had some early boyfriends that were kind of jerks. The first real boyfriend I had was physically abusive. Right away, that set me up for “all right, they’re fun to play with, but…” I left high school after my junior year. I got to fly up like a Brownie. I skipped my senior year because I had taken enough classes to graduate. I took senior English that summer, and I started at the University of Tennessee (UT) at Martin. I went from my junior year in high school to my freshman year in college, which was wonderful. I was seventeen. I was finishing up with my boyfriends. The last, really serious one got physically abusive. That really helped push me over into “I’m not really excited about this.”

Coming Out

I had feelings for women. Everyone thought I was a lesbian because I was so butch. I was always—even with the long hair—into sports and these butchie kinds of things. I think I had a butch attitude. Hell, I’m a stone butch, for Christ’s sake. Even when I was a girlie girl. I came out, I guess, at the end of my freshman year of university. I would have been about eighteen when I came out. Yay! That was great.

MM: Tell more about where you were when you came out, and your first girlfriend. How did you feel?

LL: It was at University of Tennessee Martin. I had to go to Memphis [Tennessee] to see Leon Russell in concert. This was during my drinking days. I came back to Martin, and I was so drunk that I couldn’t make it to my room. I was on the third floor, and I knew I couldn’t make it up to my room. I found my friend, Mildred, on the first floor. I knocked on her door, and asked, “Can I crash here?” She said, “Sure.” She didn’t have a roommate. They had two single beds on either side of the dorm room with the beds, the closet, and the desk one big solid piece of furniture. And then a window. I got in the other bed. She kept saying, “You can’t sleep with me,” and I said, “I’m fine.” I wanted to pass out.

She somehow got me to get into bed with her, and then she said, “You know, we’re not going to do anything.” I’m said, “Fine. I’m drunk. I want to pass out. Can we just go to sleep?” She kept telling me what wasn’t going to happen. I wasn’t able to make the first move because I was intoxicated, and I’d never made love to a woman before. Somewhere in the night, I decided, “Let’s give this a shot.” I think we started! [Laughter] This is so much better.

MM: Did she know she liked women?

LL: No, I was her first.

MM: Oh, my! You came out together!

LL: She was a virgin. She had never had sex with men or women. I had had sex with men, but not with women. That night was funny. It was the first time I had made love to a woman, and I immediately knew that I wanted to have oral sex with her. She was a robust woman, and I was a little skinny kid then [Laughter]. I climbed down her body and began to have oral sex.

The act of giving her pleasure gave me an enormous amount of pleasure. I was hooked immediately.

She leapt up, throwing me off the bed and onto the floor. I said, “What happened?” She reached down, and said, “Get back up here!” She pulled me back up.

I start again, and she says “Ahhh…” and she up and knocks me off the bed a second time. She pulls me up again, and I’m thinking, “What’s happening here?” This time, I grab a hold on her and hang on! I guess I gave her her first orgasm.

The other thing that happened for me was when I realized she was having an orgasm, I had an orgasm. That was a “whoa” moment, a real eye opener for me because I thought, “Hey, this is great.” The act of giving her pleasure gave me an enormous amount of pleasure. I was hooked immediately. Whoa! This is so much better [than men]. Much safer. After we made love, she pulled me up to kiss me, and she said, “I knew you were gay!” I’m like “OK, well.” Then she made me promise her by saying, “Don’t tell anybody.” I said “OK, fine. Don’t tell anybody.”

Her best friend came and knocked on the door the next morning. They were going to go to class and I’m there. Her best friend glances toward me in the other bed. That was my soon-to-be next girlfriend, her best friend. I finally made it up to my room, changed clothes, and made it to the cafeteria. A bunch of us were theatre nerds, and we were hanging out with the hippie-theatre-nerdy people. When I walked in, several of them got up and started applauding. [Laughter] They said, “Somebody finally got Mildred’s cherry. Well done!” “I thought you said not to tell anybody,” I said. She said, “Well, it was, you know, I just told them.”

Evidently, that triggered a lot of interest from other women, even from really straight women. All of a sudden, I had a reputation. It was a fairly small campus, and I can’t believe that I was the only lesbian. Suddenly, everybody knew. I was getting a lot of inquiries from straight girls who were mad at their boyfriends, or who had just broken up with their boyfriends, or who just wanted to dabble. I got lots of business.

From then on, I never had any problem getting a girlfriend, thank the Lord! It was a wonderful, heady time. That realization that making love with her gave me so much pleasure, and I was hooked. A few times over the next few years, if I was really intoxicated at a party and there were some guys there that I liked, I tried them a time or two, like once or twice a year.

Finally, I just said, “Eh. I think I’m fine here with women. I’m right where I need to be.” I’m not a gold-star lesbian; but I did do A and B, and I’ll stay here. That was wonderful.

MM: Did you continue seeing each other, the two of you?

LL: Yes, she and I stayed together for some time. We were dating. She was in a sorority, Delta Sigma Theta. The women of color sorority. I used to love it because her hair required a lot of attention. Women of color would have to do a lot to their hair, and then I would pull her into bed, and I would mess up her hair. “I’m late for my sorority meeting!” she would say. She would have to put a bandana on her head before leaving. As a matter of fact, I stayed in her room so much that I had to have a fire escape buddy in case of emergency. They called to say that they needed to hook yme up with somebody, and to account for me being in a room that wasn’t my room because I was there so often.

Last Boyfriend

LL: I broke Mildred’s heart. While I was with her, I went to Los Angeles (LA), California. I moved to LA with my last boyfriend. I was dwindling on going with the boys. but I met this guy from Beverly Hills. He had a Volvo and a beard. He was a really cool guy. Very different from those west Tennessee boys.

He and I hit it off. He told me, “You really don’t belong here [in Tennessee]. This is a small town, and you need to get out of here.” He talked me into moving because he was leaving. He had come there because he had grandparents there. But he wanted to be a farmer. He actually became a date farmer. He grows dates now.

I said “ok,” and we took off to LA. I had been going to go to school out there, but I didn’t know anything about out-of-state tuition. It was 1976, and Jimmy Carter was running for president. The reason I knew that was because my boyfriend’s dad was some big somebody with the Republicans out there. Yes, they lived in Beverly Hills 90210. I got the driver’s license. I was so proud.

He asked me to always wear my coveralls. We went down to Rodeo Drive, and he liked to do a big F.U. [fuck you] to all the ostentatious spending and consumerism of Beverly Hills. He trotted me out to say “Fuck You.” I was loving the swimming pools, the palm trees, and the opulence. I mean, these people were wealthy. His sister was nuts and amazing. She had amazing friends come over to go skinny dipping. These are people you’ve heard about. My boyfriend even had me meet his dad. I lived in their house for the first few weeks until I got my own apartment and job and all that stuff.

His dad called me into his den, and there was this other old fart, this other old Republican, who had come down from Sacramento. “We need to ask you some questions.”

Maybe I am responsible for Jimmy Carter getting elected in 1976. You’re welcome.

I said, “Cool.”

They said, “We’re hearing a lot about this Jimmy Carter fellow, and you’re from the South. Tell us what you think about this Jimmy Carter fellow.”

I answered, “I have no idea. I’ve never heard of Jimmy Carter. I’m from Tennessee, and he’s from Georgia.” They were very concerned, as they should be, about Jimmy Carter. I said, “I’ve never heard of the guy.”

They asked, “He’s not politically strong where you’re from in Tennessee?”

I told them, “No, sir. Never heard of him.” Then, I embellished the story when they asked me if I thought that they needed need to worry about him. I reassured them, “Oh, absolutely not.”

Maybe I am responsible for Jimmy Carter getting elected in 1976. You’re welcome. I told those California Republicans that there was no need to worry.

MM: That was your first, monumental political act.

LL: Totally. I stayed out there, and yet, I really hated LA. Too many people, too many cars. Lots of crazy people. I missed Mildred terribly. I came back home. Mildred and I had written torrid letters back and forth. That was back in the day when you mailed letters [through the US Postal Service] to each other. I had saved them all. When I came back, I dumped all my stuff in my mom and dad’s house, and I headed to the campus. I immediately began reconnecting with Mildred and with all my friends there at UT Martin. [University of Tennessee in Martin]

Family Attitudes

I was working at a Walmart, an early, early Walmart, number 107, that had just moved from Arkansas into Tennessee. My dad showed up, and he said, “You need to come home over the weekend. Mom and I need to talk to you.”

All serious, I said, “Uh oh, is somebody sick? Is Kevin okay?” [Kevin is Lenny’s brother] “Is somebody dying? Is Mom okay? Are you okay?”

He said, “Just come home this weekend at the particular time.” When I got home, they had sent my brother away. I’m thought that this is really bad news.

I said, “OK, fine, then. I’m dead! I am dead to you.”

I come in, and Mom came into the room. She has a bunch of these letters in her hand that Mildred had written to me. She was shaking. She said, “I don’t want that woman ever back in my house again. How long has this been going on?” She was sure that it was Mildred who had lured me into this lesbian lifestyle, alternative lifestyle.

I said, “Mom, it was me.”

My dad asked, “Was it Ann Detzle?” Ann had been my piano teacher forever, and she was what they called back then an “old maid.” She was kind of dyky gal, but no. That was a terrible, terrible day and night because, before it was over, Mom said to me, “I’d rather see you lying dead in a casket than to know this about you.”

MM: That must have cut you open.

LL: I was gutted by that because I loved my mother. We were close. It all came from her religious bias. I said, “OK, fine, then. I’m dead! I am dead to you.”

I talked about this a lot in therapy, obviously. I punished both my mom and me. I wouldn’t go home. I came home maybe at Christmas. I shut her out. I shut my family out because of that. I punished us both. We lost a whole lot of time together when we could have had a relationship.

Years later, we came around. It turned out that she, in fact, became a good advocate for me… though not a frontline kind of thing. There was a chaplain at church, a military preacher, that came to visit and to speak. This was around the time of the U.S. military policy about gays that was called “don’t ask, don’t tell.” After he spoke, he took questions. Somebody asked, “What do you think about ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’?” He said “We have our churches, and they have theirs.” We were “Okay, fine.”

I guess the MCC [Metropolitan Community Church] churches were Christian churches, and they were gay-friendly and often organized by gays. He said that “us” and “them” kind of thing. My mom, God bless her, said “I don’t think Jesus would be very happy with that. I don’t think Jesus would have treated them like that.”

MM: What do you think brought about her change?

LL: For one thing, me not changing. And me being me.

MM: And she loved you.

LL: She loved me. Though we had those years of estrangement, I think she was ready to forgive and forget. ready to move on. I remember how it was tough. Sometimes, I would bring home a different girl. I was partnered with Kecia Cunningham for many years. Mom would have us over for Christmas. We’d have all the gifts wrapped for them. I made it a point to put “from Lenny and Kecia” on all of our gifts when we put them all under the tree.

Mom was a notorious snoop. She’d look under the tree to see what was there, and what had been added, the new gifts. After dinner, she snuck back and whispered, “I need to talk to you.” I said “What is it?” She said, “All the gifts that say ‘from Lenny and Kecia’.” This was Christmas Eve. “I don’t think I have anything under the tree for her.” I said “You need to fix that.”

MM: Good for you to tell her that.

LL: She got in the car and went to Walgreens or Walmart or whatever. And she got some things. Christmas morning, there were wrapped presents under the tree with Kecia’s name on them.

Oh, my God! There are queers everywhere in this family! Everybody’s queer but me.

MM: There was nothing under the tree for the two of you together?

LL: You know, I really don’t remember that. But she came around. And I think she began to understand that, first of all, I was not going to change. My brother came out when he grew up. I didn’t know this then, and I found out years later that my dad was a closet homosexual.

That also gave me some insight as to her drastic reaction about finding out about me “Oh, my God! There are queers everywhere in this family! Everybody’s queer but me.” Again, that was an insight because I didn’t know about my dad.

MM: How did you find out?

LL: My brother told me when I was an adult.

MM: How did he find out?

LL: Well, he’s a gay man. Once he got involved in the gay community in that little town, it’s a little tiny town, he found out that Dad had a bit of a reputation. But Dad was strictly on the down-low because he was in the church. He was a deacon, you know, a fine upstanding man. He was “on the DL,” the down-low. In the gay and lesbian community, I think it was known. They were very closeted then, and they protected each other’s secrets. But within their community, they talked about each other.

MM: Oh, I love that.

LL: Yes, my brother Kevin verified it for me. I put together some things over the years. Comments that he’d made and things that now made sense. I remembered a trip home. Dad always went fishing. He was self-employed as a piano tuner. That’s why he became self-employed. He loved that he’d get Fridays off, got the day off whenever. My dad and his dad would go fishing every Friday down at Reelfoot Lake, the world’s largest natural fish hatchery. They kept an old boat down there.

I loved to go fishing sometimes when I was home. I grew up riding down there with Dad in the old car. There were some young women walking down the road as we passed, and I remember Dad saying, “Well there’s some pretty girls here for you.” [Laughter] I’m like… [looks around in surprise.]

He did things to tell me, but he never came out to me until later in life, much later in life. I was home, and he was out in his little shop. He also did electronic work (again that fix it thing that runs in the family). We were out there and we were just talking a little. I don’t know who brought it up, but he said, “You know I’m gay. I figured you knew, and I just wanted to say, by the way, I’m gay.”

I said, “Well, thank you for telling me.” I had some suspicions. I had heard some stories. It was probably pretty close to him moving into some dementia, so it was important for him to say that to me, I guess, at some point. For him to come out. I appreciated that very much. He passed in 2012.

Career Choices: Coal Mining

After I spent some time in Los Angeles (California), helping Jimmy Carter get elected, I came home, had that big falling out with my mom, and ended up in Birmingham, Alabama. I was going to go to pharmacy school. I already had a couple years of undergrad as a Psychology major at University of Tennessee in Martin. Then, I thought I wanted to be a pharmacist. If we can make drugs that heal bodies, why can’t we make drugs to heal minds? Sort of my theory.

I wanted to study pharmacology, and Samford University in Birmingham had a pharmacology school. Obviously, pharmacy school meant a lot of study and discipline. I was still pretty young, and liked to drink and chase girls. I did okay, but I wasn’t making great grades. There had been a terrible storm in Birmingham, which was unusual, and I couldn’t get down there in time to set up off-campus housing. I got stuck in the freshman girl’s dorm.

MM: Just your meat and potatoes, honey.

LL: [Laughter] Samford is a Baptist college, and they had a curfew. If I stayed out late, they locked the gates. Freshman girl’s dorm was a fun place to be for a young dyke. I remember that I had a picture of my girlfriend while my roommates each had little photos of their boyfriends. I had a big (11×14) photo of Wanda, who was the girlfriend after Mildred. That was a clue for them.

I was doing a lot of drinking. I wasn’t making passes at anyone. I had a girlfriend. I was enjoying the view, for sure, of young women around me.

I don’t really want to be a pharmacist. They never get laid!

One time I came in late, and snuck in. One of the dormitory RA’s [Resident Advisor] leaned in on me and said, “We don’t really like you here, and we can’t wait for you to leave here.” I’m thinking, “Me, too!”

She [the RA] said, “Well, we know all about you, and you’re coming in here late, and drinking. We think you’re a bad influence on these young women.”

I said, “Fine, and fuck you, really.”

They were acting like, “We’re keeping an eye on you.” The RA [resident advisor] intimated that they knew I was gay. I thought, “Yeah, whatever.” To have someone try to muscle me like that, that’s not going to work. I left everybody alone. I decided to get the hell out of there as soon as I could. I wasn’t that welcome. The only thing convenient about living in the dormitory was that it was easy to walk to my class. But other than that, it was cramping my style, for sure.

I got my little apartment, and I was working at a bartending job… and not doing my technician time. You had to work a certain amount of unpaid apprentice time with a pharmacist. I had just bought a new Ford F-150 truck, and I had to work for money. I was making good money bartending.

At some point, it just all came together. I said, “I don’t really want to be a pharmacist. They never get laid!” I was sure of that. Motivation for everything. You hear about your priests, your preacher, your mailman, and your doctor getting laid and having affairs. But you never hear about your pharmacist, you never do. I thought, “Screw it. I’m going to quit.” They were pressuring me to do these intern hours. How was I going to do that? I already had a car payment and rent. I couldn’t make that work. I decided that night that I was going to quit.

My lab partner, Molly Roberts, was from England. She had this accent. I told her I was going to quit and drop out. I was going to my advisor and quit. Let’s don’t put any more money into this. About this time, I also had a big fight with my boss at the Chinese restaurant. I told him “Screw you and I quit!” I’m like that, a real smart aleck.

Molly and I were sitting there getting really high and listening to Pink Floyd’s album, “Dark Side of the Moon.” I said, “I need a job. I just quit school, I just quit my job. I need a job.”

Molly said, “My dad was talking about how they’re going to hire women for the very first time in the coal mine.” I said, “Wait—there are coal mines in Alabama?” Her dad worked for Jim Walter Resource—The Jim Walter Modular Homes. They evidently were a large company, and they owned a lot of other interests including mines and mineral rights. They owned mines in several states, including Alabama.

Molly had heard her dad say that the federal government was forcing them to hire women. No one was doing it voluntarily, that’s for sure. They were being forced to hire women. They were going to bring in a class, weed them out, and then, let that first group go in. You had to have a good bit of orientation before they actually let you go work in the coal mine. I distinctly remember her saying, “And you know, starting pay was going to be $7.45 an hour.” Minimum wage then was maybe $2.50 an hour.

We were the first group of women to go into the deep mines.

And these were deep mines. It was about a quarter of a mile down.

It was a big raise, and I thought now, that will take care of the truck payment. I wanted this job. I had no idea what it meant. I was just listening to how much I was going to get paid. Molly set up a meeting with her dad. I went to buy the best bottle of scotch I could find in Birmingham, took it into his living room, sat down, gave him the bottle of scotch, and talked him into hiring me. He told me, “You don’t want to do this. This is a hard job. This is a dangerous job. Go back to school.” But I was done with pharmacy studies. I was moving on, I told him. I was ready to consider some other career. And he said, “But not coal mining. Come on, who thinks of that?” Nobody. But I was thinking of $7.45 an hour.

I talked him into it. He made one request. He said, “I’m a company man. Basically, you’re not earning us any money for the first year. We’re teaching you how to do whatever, and you won’t generate any profit for us. You’re just a worker bee for a minute.” He said, “Will you commit to one year?” I said I would. So, he pulled the strings, and I was in that first class of thirteen women.

We were “the thirteen.” I don’t know why thirteen. I thought that was an interesting pick. I was in the first class of women the United Mineworkers Local there. We were the first group of women to go into the deep mines. And these were deep mines. It was about a quarter of a mile down. On the elevator down, your ears popped several times. It was an amazing place to work. And the male workers were very hostile. They were very inhospitable. They were not happy to have us women.

They were hostile and threatening and abusive. In that group of thirteen, there were three, maybe four, women of color. I used to say when we came out, “We were unirace and unisex.” We had the goggles, the hats, and the respirators, wearing coveralls and boots. And we were all covered in coal dust and filthy.

Actually, I loved it because it was so interesting. It was like nothing I had ever done before. I kind of liked being down in the ground. It was really cool. And scary and dangerous. But that’s where the seed was planted for my apprenticeship to be an electrician.

Because of the methane in the air in the coal mine, everything was powered by electric. The electricians were gods. They ruled. They got all the overtime. They made all the money. They’d come in and something would shut down. Anytime something would shut down, there’s no money for the company. These electrician guys would come in and fix everything.

I was thinking, “Whoa, there you go.” They were the ‘alphas’ for sure. I was like, “Wow!” At that point, I hadn’t considered going into the trades. It was that time when the trade unions were finally beginning to be forced to hire women and minorities. The federal government had to make them do it. I knew I wasn’t going to be a coal miner. I figured I would do my year and get the hell out of there. And being an electrician seemed very desirable. They’re cool.

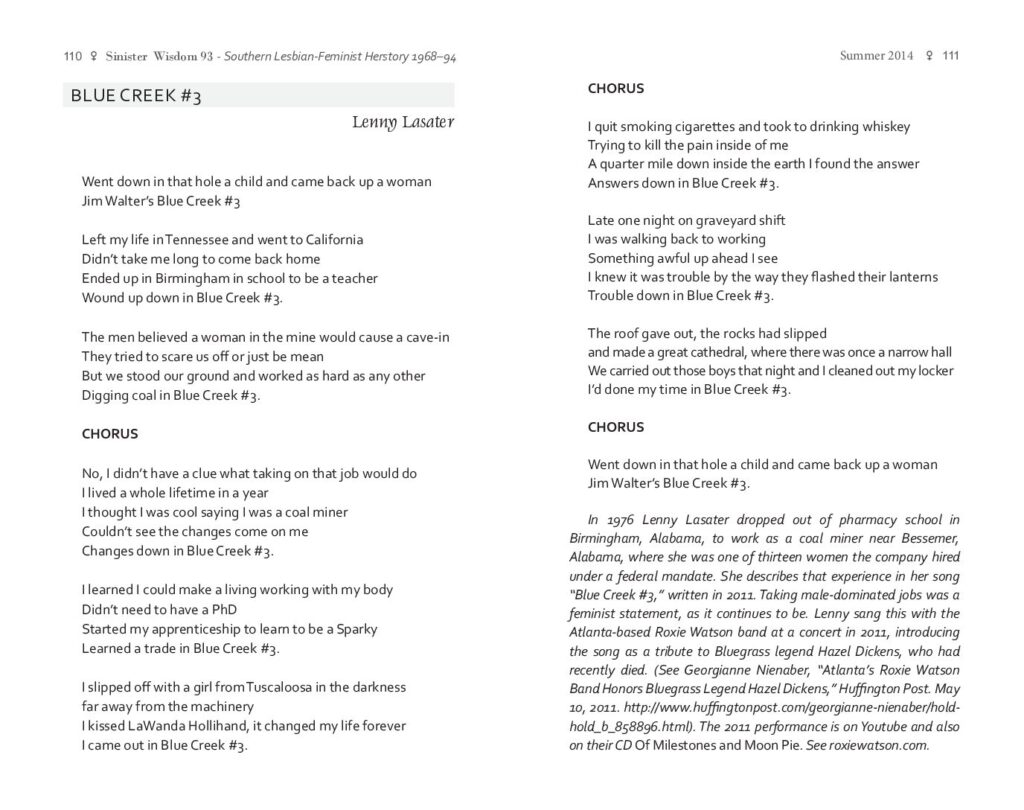

Some years later, I wrote a song, “Blue Creek #3,” about that work. In it, there is a woman from Tuscaloosa, a gorgeous little gal, and we did sneak off in the tunnels and turn our little lights off to kiss. [Lenny motions as if turning off her helmet headlamp.]

That was really fun. I was still not a big old bull dagger yet. I was still kind of a kid and kind of scrawny. I probably weighed 150 pounds, maybe, and I’m tall. I had several fellows come up and lean on me, lean in on me pretty hard, and try to push me around. They threatened me, physically threatened me, sexually. They said all kinds of horrible shit to us all the time. I kind of understood that whole “alpha” thing, and just understood that I have to be bigger and better than they are, and not be afraid, not show fear. I didn’t quite make the year. I had witnessed a couple of accidents.

MM: Tell about that.

LL: There was a guy who had a heart attack, an older fellow. We had all been taught CPR [Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation], and those kinds of thing. I remembered that the old guy chewed tobacco, and not looking forward to doing the compressions. You do some mouth-to-mouth breaths, you do some compression, and then, you do some breaths again. I thought, nope, he’s got tobacco. Make sure you get the tobacco out.

The foreman or whoever was down there was so freaked out. He continued to do CPR for way longer than you’re supposed to. You’re supposed to tag team out. There were several of us around, and we said, “Let us come in.” He said, “No, no.” He just kept going, with sweat pouring off of him. We were freaking out, too. He was not effective any more, we said, and he needed to let one of us in and for him to rotate out. That really upset me. The old man did not survive, and I felt really bad. We were all standing there, and we could have helped him. But the boss said had said no.

Then there’s the incident that I refer to in the song that I wrote. The coal mine was a very dangerous place. We had to constantly be pinning the ceiling and putting timbers to hold everything up because we were cutting these giant tunnels out of the middle of the Earth. There was a lot of gravity, and there was a lot of weight.

We were constantly “pinning the ceiling,” putting up these huge girders. They were big, U-shaped steel channels that were 10 feet long and four or five feet wide. We’d drill and then stick in these pins. Then, we were putting up actual wooden timber that we had cut to size, running curtains around to move the air. Most of the time, we could actually stand up and walk, and occasionally it would get narrow. They had these giant machines called “continuous miners” that would cut out these huge swaths, There were four of them, constantly moving. They would move the rail forward and the belts forward. It was a constantly evolving, moving thing that was growing exponentially every shift.

I can remember coming in sometimes where there would be a low place. I walked in, and suddenly there was this huge room. I’d say, “Wow!” The others said, “Yeah, last night the ceiling fell in.” That was one of the lines I wrote in the song. I wrote, “It was a huge cathedral where once there was a narrow hall.” We were aware of that kind of thing.

On the night referred to in the song, there was a young foreman, a red headed kid, who was moving some gear from the train that brought in equipment. They were setting up a come-along hoist that they hooked up to one of these channels that we had installed. This was in an older part of the mine. They were picking stuff up at the end of that transfer, and setting it on the ground.

When they did that, the shoulder shouldn’t have been used. They shouldn’t have used the channel buckle for the weight they were picking up. A big, flat slab of material or rock, slid off and hit the foreman on the back of the head. He had on a hard hat, of course. But, yes, I just happened to be walking back to where we kept our lunch to get to my lunchbox and thermos. They were all down there flashing their head lights, signifying, “Come now. Hurry, hurry. Trouble, trouble.” I went running down there. He was lying on the ground, and he was pretty badly injured. One guy said, “You’re a girl, you’re a woman, comfort him.” I sat down and held his head in my lap because we had to wait for the man-bus to move him out. It took twenty to thirty minutes to get from the top down to where we were. The mine was well spread out.

During that time, while holding his head and saying comforting things to him, telling him that it was going to be ok, they were hunting for towels or t-shirts to wrap around his head. Anyway, you know, “You’re going to be ok.” I was freaked the fuck out, and running on adrenalin. I kept repeating, “You’re going to be ok. You’re going to be ok.” I rode out with him. We didn’t want to move him around a lot, so we all got up together and got on the thing to ride out of the mine. Once we were up, there was an ambulance waiting that took him in.

He did not survive. He had a young wife and a couple young children. In the song, I indicate that that was my last night there. I said, “those boys” but there was just one guy.

It was a few weeks later that I had rotated off to another group called the belt crew. We were throwing this stuff through, and it bounced back to hit me on the inside of my leg. I had a big cut. That ended me up in the emergency room that night getting some stitches.

That was the night I came back to say, “Fuck this!” We had chains with our clothing in these baskets that we would take up to the ceiling and then put a padlock on it. That way, no one could steal it. We had a locker room, but we had never seen it. I was bringing the chain down with my basket of street clothes because we’d have to shower there before we could go home. I showered, and I went home. The next day, I called Molly’s dad to tell him, “I’m not going back. I’m sorry, I told you I was going to do a year. But you were right, I know this is not a job I want to do.”

You know, really, it was not so much the guy who had the heart attack. It was the other guy getting hurt like that, and then, my own injury. I just thought, this is nuts, this is nuts. I made it about eight months.

Career Choices: Union Work

Right after that I moved back to Nashville. I’d had enough of Alabama. The queer community in Birmingham felt as if they were third-class citizens. They considered themselves to be third-class citizens because there was so much homophobia. There was a lot of internalized homophobia, too, in the community, and a lot of misogyny.

I remember being very aware of the pecking order in the community. Of course, it’s the deep South, and this was in the late 1970s. It was hard to know where the gay men were. White, heterosexual men were at the top of the pecking order. Next were white men, maybe gay, but not out. Then, white women; then, white lesbians. The black lesbians were the bottom rung. There were a lot of real unhappy people there in the community.

It was very much a bar culture, and there was a lot of drag stuff going on. In those times, thank god for disco. We were a depressed community. The queer community in Birmingham seemed very depressed. I had had enough. I’m from Tennessee. You can keep Alabama. I went back to Nashville, and that’s when I started my apprenticeship with the IBEW, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. I loved getting those letters, “Dear Sir, and Brother.”

“If you want to keep getting this federal money, you’d better bring in some different people.”

They began to actively recruit women and minorities in the late 1970s because they had to.

MM: How did you get into that? My impression was that the unions were pretty tight. It was hard to get in even if you were a man, but especially if you were a woman.

LL: Once again, the federal government was short sighted. I was in the Nashville local union 429. Nashville had a good-sized union there. Trade unions weren’t very strong in the South at all, anyway, not in the 1970s. The Tennessee Valley Authority, aka TVA, was building some nuclear power plants. They organized those workers.

MM: Yes, I worked construction on one of those.

LL: The trade unions organized. However, they weren’t very strong the way they were up North. Hell, Georgia is what’s called a “right to work state,” meaning you can’t be forced to join a union. Tennessee was a little different. Still, the unions weren’t that strong. Anyway, I knew I was ready to be an electrician. In fact, I went to the IBEW [International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers] to ask about getting in, but they had already picked their class for that year. They were only going to pick the minimum required.

Their joint apprenticeship and training committees and programs had started taking federal money to help subsidize those programs. After a few years of that subsidy, the federal government said, “OK, you’re taking our money. Where are the women and minorities?” Right? The companies said, “Oh, we don’t have any.” I said, “If you want to keep getting this federal money, you’d better bring in some different people.” They began to actively recruit women and minorities in the late 1970s because they had to do it.

I went to the IBEW, and they said, “No, sorry. We’re full.” In Nashville, there was this giant building we called the Round House, and it was where many trades had their offices. That included the pipefitters, the plumbers, the electrical workers, carpenters… they were all in this building. I’m walking out after they told me no, and this guy came out of the office, saying, “Hey, are you trying to get in the apprenticeship program?” I said, “Yes, sir. I’m trying to get in the electrical union 429.”

He said, “Oh hell, you don’t want to be an electrician, come on in here.” He was with the pipefitters local, the steamfitters and pipefitters. They needed some women. I started the whole application process with him. It included some health checks and some aptitude tests, where you put slot A into tab B. I had to have certain high school math and algebra. I’m said, “Dude, I’ve been in pharmacy school, ok. No problem.”

MM: It was the “General Aptitude Test Battery.”

LL: There you go. I went through all of that shit. For that summer, I actually went to work for a non-union electrical contractor just to get my feet wet, to see what it was like. I worked at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, a new building that had just gone up. I remember learning a lot there about non-union versus union, or what they called “open shop.” I was there, and it was summer. We were working, and we weren’t making much money, but it wasn’t bad. It was trades. It didn’t pay as much as apprenticeship in the union, which got regular raises.

MM: You went to the pipefitter’s union?

LL: No, I was going through the application process with the pipefitter’s union while I was working for a non-union electrical contractor that summer, working on a construction site, just to get some experience. I thought that maybe I didn’t want to be an electrician. I wanted to test drive this. I did, and I thought it was pretty cool. They were a little less hostile there. Maybe two or three other women were on the site with hundreds and hundreds of men. You know, maybe there would be one female electrician, maybe one plumber, and maybe one carpenter. Certainly not many.

I went to the office and said, “I want you to hire me.” The guy that hired me told me, “If you ever have any trouble, you come to me.” I didn’t understand the chain of command at the time. He was at the top of the chain, and between him and me, there was a foreman and a general foreman. And then, there was the boss of the whole.

I had been seeing this big sign saying “This building is being built by so and so,” listing who was the general contractor. All summer, when we would get our checks, we would look at our checks and kind of compare. All of us who were in our first six months, we were all just starting. Toward the end of the summer, this kid shows up, well-tanned, and he just sort of pops in, saying, “Hey, how are you doing?”

“Oh, where you been all summer?” We asked.

“I’ve been on vacation.” He was a first-year apprentice, too. Next week, he gets his check. We were all standing around, and I looked at his check. His was significantly more than mine, and more than some of the other boys that I’d been with. Significantly more.

I said, “Hey! What’s the deal? We’ve been here all summer establishing our ‘merit shop,’ and you just pop in at the end of the summer. Why are you making more?”

I didn’t ask the right people that question. That evening, I went into the office of the man who hired me, who was the owner of the company, and demanded a raise. I said, “I’ve been working for you all summer. I’m going to get in the union here. So, you know, make this work.”

He was flabbergasted that I walked in and demanded a raise. He said, “Listen, let me talk to your boss there on the job, and we’ll let you know tomorrow.”

I went in to work the next morning, and the general foreman was standing there waiting for me, motioning with his finger for me to come in. He was so pissed at me because I went over his head. He tore me a new asshole about chain of command. He said, “Don’t you ever leave my job and go talk to… If you’ve got a problem, you come to me!”

I said, “That’s what he said! You know I’m going to get in the union here. So, make this work.” He really did hammer me. He walked me out to that big sign, pointing, “What does it say there?” And I answered, “Joe Blow Harris-Johnson Contractor,” whatever. He asked me, “That kid who got paid more, what was his name?” I answered, “Harris-Johnson whatever.” It was the same last name. He said, “That’s why his check was bigger than yours. Because his daddy is overseeing this entire project,” he said. “Look, it’s called married shop.”

“You may be gay, and what you do in your off time is your business.

But here on the job, it would be in your best interest not to talk about that,

not to be too demonstratively butch or gay or whatever.

It would be safer for you,” he said.

They were not bound by any particular pay scale. They could pay you what they wanted. After he tore me a new asshole, he showed me that sign to help me understand about the chain of command. Then, he brings me back in his office and said, “Listen, you’re really smart.” He admired my chutzpah! [Laughter] Even though I had done it wrong with the chain of command, he offered me work on the fire alarm crew, which was very complicated. You really needed to be pretty smart to put in fire alarm systems. It was a thirty-floor high building. He said, “You’re really smart, and I think you’re going to be a great electrician.” And I realized that I really didn’t want to be a pipefitter. He offered me that upgrade, and he said, “We’re going to get you a little more money.” I said, “Great!”

I got with this other crew, and you could tell right away they had more conditions. They had a nicer place to put up, they had a refrigerator for their food, clean bathroom, toilet paper. You’ve been on construction sites, Merril, and you know how they vary. I could see right away this was the Cadillac kind of job. I was going to learn a whole lot more doing this. I got home the next day, and my answering machine light was blinking. “This is Marshall Devine at the IBEW 429. Listen, we have an opening. We had a gal drop out and we need another female. Are you still interested? If so, call me back at this number.” [Laughter]

I went in the next day to tell my boss, who had just given me the raise and the better job, that I was leaving to go work for the IBEW 429. He said, “I’m really going to discourage you from doing that. They sell you a bill of goods. It’s no good, especially here in the South. You won’t get to keep working, you won’t get to stay home, you’ll have to travel. You’ll make more money with us. You’re really smart, don’t do it, don’t do it, don’t do it.” And I said, “You can’t guarantee me anything. I already see how this kind of works, who you know, 0r who you blow kind of thing.”

I probably would have done well there, because I’m pretty clever. I was guaranteed pay over with the IBEW [International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers], and I liked the idea of it being a more structured situation. I said, “No, Sir. Thank you.” I went over to start my apprenticeship with them late that summer. I was the second woman to go through IBEW 429. The woman who started a year before me had a father and brothers who were plumbers, and they were all in the trades.

I love Marshall Devine. He was the apprenticeship director. I went into his office and he was very clear. He said, “You may be gay, and what you do in your off time is your business. But here on the job, it would be in your best interest not to talk about that, not to be too demonstratively butch or gay or whatever. It would be safer for you,” he said, “to keep it that way. I’m not saying you have to, because by federal law I can’t. I think this would be in your best interest.” I guess he read me. Hello, look at me! I think I still had my long hair then, but I’m a dyke for Christ’s sake. [Laughter]

MM: You were pretty dykey even with your long hair.

LL: Yes, he advised me to keep on the down low. I always liked him. I took him a good bottle of scotch, too. That’s a good way to make friends and influence strangers. Males anyway. I remember I had moved, and I had a new address. I went to his office and said, “Marshall, I need to give you my new address.”

He had this rolodex, flipping through it. Every once in a while, there’d be this big, black, magic marker M on a card. When he came to mine, it had a big, black, magic marker M. He pulls it out, takes a pen, marks off the whole address, puts in the new and pops it back in. I said, “Marshall, I’m curious. You’re going through this rolodex, and occasionally, I see this big, magic marker M, and you’ve got a magic marker M on my name, too. What does that mean?” He says, “Oh, that means minorities. When they call us, the EEOC [Equal Opportunity Employment Commission], or someone from the government in Washington, DC, to ask us how many minorities we’ve got, I can go through really quickly and count them. If you were black, you’d be a double M.” [Laughter]

The guys I worked with were hostile. They were not very welcoming. I felt like there were more protections within the union. The unions answered to the EEOC [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission] and OSHA [Occupational Safety and Health Administration]. All these jobs were usually big jobs. The guys weren’t too excited about having women working with them. As I said, I was number two or number three coming through. We were trailblazing with local union 429. I have since heard that that was true in the late 1970s. A lot of women were the first ones to go through, and they pretty much met with the same hostility.

Guys would come up to me and tell me, “If you do somehow manage to tap out (meaning to get your journeyman card), no self-respecting man is going to ever take orders from a woman.”

I told them, “Well, if I’m a journeyman, and if I got an apprentice, which I’m pretty sure I’ll have, and if he doesn’t do what I say, then, I’m going to kick his ass.” [Laughter]

They were so threatened. I mean, what do you think they would have me do? They gave me a lot of “gofer” jobs there, too. You know, go get this for us, go get that. In the trailer where we ate lunch, I was sweeping up some stuff. No one told me to do that. I was just doing it. A guy walked in and said, “There’s a tool you know how to use: the broom.”

MM: They hate it when we get into their territory like that because we can see what they do there. And what they do is they touch each other a lot. [Laughter] When I went to join the carpenter’s local union, they tried to discourage me by telling me that the work was heavy lifting, that it would ruin my womb, and that I wouldn’t be able to have children. And I said, “Honey, I have three children. I need this job to feed them.” Ruin my womb? I thought, where the hell did they get that?

LL: I came in on the tail end of that class. Somebody quit, and I came in. I hadn’t been vetted yet. The good news was that it was so funny. I was in this big building, and I went over to the plumber and pipefitter office. I asked if they had my file. The guy said sure. I took it to walk across the hall to the IBEW [International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers]. It was the same thing, the test and the aptitude at the IBEW that I had already done. He said, “Wait a minute, wait a minute. You don’t want to be an electrician.” I said, “No. I don’t want to be a pipefitter.” [Laughter]

I took my file over to Marshall, and they got me right in. I had to be interviewed by the apprenticeship committee. I’ll always remember this. I can’t remember that guy’s name, but he was such an old bastard. He had a reputation of being an old bastard to everybody. But he was especially hostile about women. When I went in for my interview, he was sitting back, you know, looking at me as if he hated me.

The rest of the guys were pretty nice. Seven or eight guys there at the table were asking me questions, like where I came from, and, of course, the big question, why did I want to be an electrician. I said, “I worked in the coal mine, and I saw how the electricians were the ‘alphas’ there. They fixed everything. I’m not going to be in college any more. If I’m going to be in the trades, this would be the trade. These are the smartest guys. These are the smartest people. I want to be an electrician. I’m smart.” He reared back and said, “Are you here looking for a husband?” I told him, “No, sir, I’m not.” Of course, Marshall gave me a side-eye look.

MM: Right, don’t tell them that you’re a lesbian.

LL: “No, sir, I’m not looking for a husband.” Then, a few more of the questions. Back then, apprenticeship was four years, and now, it’s now five. He said, “You know, four years is a long time. Any chance you might get pregnant in the next four years?” I look over at Marshall. Then, I said, “No, sir, no. I don’t think you have to worry.”

He said, “You know, we’re investing a lot of money. If you were here a year or two, and then, you got pregnant, we’ve wasted all that money.”

I said, “No, sir. I’m not planning on getting pregnant in the next four years. If I do, you’ll be the first one I’ll call.” [Laughter] The bastard.

I think I’m smart, I’m clever, and I’m entertaining; and the guys seemed like they were kind of warming up to me. But not this son-of-a-bitch. They were asking me friendlier and friendlier questions. Then, at one point, they were all saying, “I think we’ve got everything we need here, Ms. Lasater.” Then, he said, “Wait just a minute. This is not a glamorous job. This is a dangerous job, a hard job, a physical job.”

“There are plenty of other places, like beautician school or cosmetology or something like that. You’ll be fine. This was just algebra and physics, Ohm’s Law.

It’s way too complicated for a gal like you.”

I’d been working all summer for that other contractor, and most of the time, I spent cutting and threading pipe on a pipe threading machine. We had oiled it up. I held up my hands, and you could see the callouses and the stain of the oil. I said, “Sir, I have no illusion that this is a glamorous job. I understand it’s physical. I understand that it’s going to be hard and physically demanding, and I can meet it. I can do it.” I got in. And the very first year there, I got into some trouble over my attendance. [Laughter]

MM: What happened?

LL: Well, I was doing fine, making great grades. I had the top scores in my class. But my friends visited me, or a young lady would come to see me, and I would miss class. What I didn’t know was that we had a limited number of absences and “tardies” [coming late to class]. I was well known for being tardy. A friend came to visit me, and I was laid out in bed. I knew to go to a Doc-in-a-Box [urgent care center] to get an excused absence.

But then, I got called in for a six-month evaluation. A lot of the boys couldn’t cut it. If you weren’t making certain grades, they were going to weed you out. Then, they had this other evaluation for us with the apprentice committee. I got called in, and we were standing there in the school where we had classes, waiting to get in to see the committee. It’s the same place where I had been interviewed before by that old bastard and the others. There were about twelve guys out there, and I came walking up. They asked, “What are you doing here? You make really good grades.” I said, “I had some issues with absences.” The others were all called in there because their grades were bad. I think I was the only one there because of attendance issues.

When Marshall walked up and said, “Who’s going to be first?” I said, “Me.” I figured that I should get in there now, when they’re not pissed off, when they haven’t heard any other stories. I walked in, and the old bastard that said all that to me was sitting at the desk. He said, “Oh, well. I knew we’d be seeing you back in here.” He didn’t look at my paperwork. He said, “Yeah, I figured this job was too hard for you. And obviously, the school part of it was just too demanding for you. There’s no shame in that. It’s all right, you know. You can go. There are plenty of other places, like beautician school or cosmetology or something like that. You’ll be fine. This was just algebra and physics, Ohm’s Law. It’s way too complicated for a gal like you.”

The other fellow sitting next to him leaned over and pointed to my grades. I had something like a 98 average, near perfect, and he said, “She’s here because of attendance, not grades.” The old bastard said, “Well, maybe this isn’t demanding or challenging enough for you.” [Laughter] I thought, make up your mind.

Then, Marshall rolled it out and said, “She has very good grades. But she has one, two, three, unexcused absences; and one, two, three, four, five, six, seven tardies.”

I said, “Seven tardies!” [Laughter] I thought I was tight with my teacher, but he would mark down when I was late. I said, “What do you want me to do?” He said, “If you miss one more, that actually puts you over the limit.” I said, “That third unexcused absence is the last one. I got a paper right here from the doctor that says I was sick last Tuesday.” He took off that absence, but the seven tardies kind of put me out. I was on lock-down, you know, best not miss any more time or be late.

Anyway, I didn’t ever have to see the committee again. They were convinced that they were going to run me off. They actually said, “This isn’t challenging enough for you!” [Laughter] I thought, “You just don’t want me to be an electrician.”

MM: Tell me about going in for yourself and starting your own company.

LL: That was a little later. After I topped out [became a journeyman], I immediately got laid off. Once I was making journeyman pay, it was sort of par for the course, women or men, to be laid off. I worked for a lot of guys who actually did say to me, “I’m proud to have you. You are a good worker, you’re smart, you come in on time, and you don’t tear up things. I wish I had a crew just like you, a whole crew just like you.” I was good and smart, and I did well.

When I was working with them individually, with one guy at a time, I would sort of bring them along. I stayed closeted, and I gained their respect. I knew I just had to dig in, do the work, and show them I wasn’t scared. I had to show them I wasn’t stupid, and show them that I could handle the physical demand. And the mental demand. Even when they made me do all the shit they weren’t supposed to do. I did it, and secretly, some of the other guys would help me.

I heard that the Savannah River Plant was hiring. [The Savannah River Plant, located in Aiken, South Carolina, 25 miles from Augusta, Georgia, was built as a nuclear weapons refinery. At that time, it was refining plutonium for the National Aeronautics Space Administration.] I moved down to Augusta to work there from 1984 to 1986. That’s how I ended up in Georgia. There wasn’t much other work.

On the weekends, I would go to Atlanta. Augusta is kind of like Birmingham. The bars in Augusta were full of unhappy people, unhappy queers who were having to be closeted because they were at the military base, Fort Gordon. It was kind of the same feeling as in Alabama, like we’re the lowest of the low. There was a lot of internalized homophobia, a lot of depression, a lot of alcoholism. I fit right in with the drinking for sure. But I hated Augusta. It’s a pretty town where they play golf tournaments, but I was going back and forth to Atlanta because there were a lot of pretty girls in Atlanta.

In 1986, I moved to Atlanta. I was with Marilyn then, a beautiful, French-Canadian, red-headed Scorpio [astrological sign]. The local union here in Atlanta was 613. I was the “traveler” because my card was with the Nashville local. That meant for me, I was the last hired, the first fired. Again, there wasn’t that much work down here. We still had to travel substantially to keep jobs. We occasionally worked some of the downtown stuff, big stuff. A lot of stuff didn’t go union [wasn’t unionized]. I ended up traveling back to Nashville, Tennessee, to work on the Saturn plant. Then, I traveled up East.

People were always talking about the overtime in New York. They said that if you go up to New York, you could make a ton of overtime working on the subways. I went up there, and spent a few weeks with a guy. All he wanted to do was hit the horse track. I was going out in the morning in the freezing cold. We were staying at his house in New Jersey and going all around, trying to sign the books on all these local unions. There were tons of locals [union shops], all within thirty miles of that area.

What I didn’t know was that this guy’s wife was back in Nashville, and he had told her that he was going up to New Jersey with an electrician “buddy” to get some work, some of that overtime. What he failed to mention to her was that I was female. His neighbor, who knew them, called the wife. He said, “Hey, you know, I see your husband is here with that gal in the Toyota.” Then, the wife called him, mad. He told her, “Oh, no, it’s not like that, honey.”

So, I had to hit the road. [Laughter] I came back to Tennessee. I was missing Tennessee, being away from my home, away from my girlfriend. The guy back there with the non-union shop was right. I was going to have to travel. There was work, and then, it was gone. I would have to travel to keep all these union jobs. It was hard.

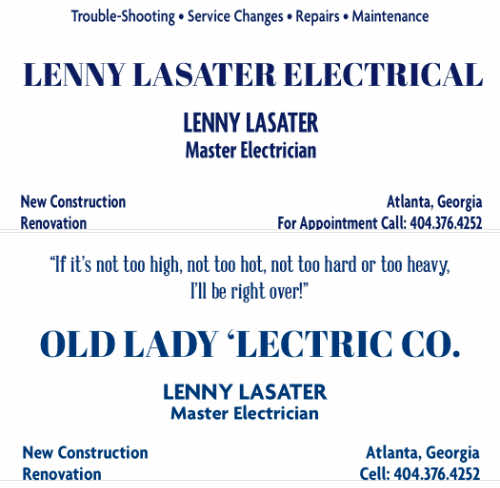

Career Choices: Lenny Lasater Electrical

In 1990, I decided that I was going to start learning to do some residential work, which I’d never done. I’d been trained in heavy industrial and large commercial, but not residential. I thought it was baloney. We all did. But I started learning and fixing a few things, thinking, how hard can it be pulling Romex [electrical wire]? The community also liked the idea of having a woman electrician.

I’m grateful that our society has turned around to where I feel like

I never have to hide who I am. I mean, I think for a minute there,

it was kind of trendy to have a lesbian electrician.

The lesbian community here in Atlanta was very much interested in having women plumbers, woman electricians, women carpenters, and women who worked on heating and air conditioning. I was one of a few here. Kathy Herman kind of took me under her wing, and she was teaching me how residential was different. I needed to understand how a house was framed out. In residential work, I was often working not on the new construction. I was looking at it after the fact. I needed to have a spatial understanding of what is behind the wall, of how I’m going to run a wire from point A to point B. I’m not running conduit. It is different that way.

I began to understand how to do residential electrical work. The cool thing about that was that it didn’t require a lot of specialized tools. There was a lot of it that I could do by myself. I didn’t need a helper, necessarily. That first winter (1990), I had to borrow a little money from my dad to get through the winter because work dries up then. After that, it was word of mouth. I’ve been blessed with plenty of work since then. “Lenny Lasater Electrical” came into being in 1990. It’s been paying its bills ever since. I’m really grateful for that.

Working with Cherry Omega

MM: Do you work all by yourself, or do you have other people working with your or for you?

LL: Occasionally I’d get on jobs where I’d have to have other people. I’ve had some helpers and apprentices throughout my career. Most of them wanted to learn, and then. go off on their own to make good money. I was actually the master signer for three different guys to get their license. I felt good about that, that I could pass it on, getting my master’s license. I had to get it in Georgia because Tennessee had no affiliation with the state government and the union.

It’s like my friend up in Michigan. She topped out, and she got her state license from Michigan. Not so in Tennessee. Oh, no, no, no. I had to take a test and sit for a separate master’s license in Georgia. I was very, you know, I hated it. It was one of those day-long tests, and that was right when I was getting sober. I sat and took every test to get my non-restricted license.

MM: Tell us about that.

LL: Cherry Omega is part of that. Cherry was a lesbian electrician in this local Atlanta union 613. I remember one of the first jobs I came on when some of the guys came up to me and said, “We’ve got some women in our union here, and some of them are gay.” I was still keeping kind of a low profile, even after I topped out. I understood that it could be dangerous, you know. About Cherry Omega, they said, “We’ve got this one, and she wears these gay t-shirts, and gay this, and gay that, and she’s all up in your face.” I remember the first time that I met her. I knew she was the one that they had been talking about. [Laughter] I was the nice one. Even after I did come out, I was the nice one. I met Cherry, and of course, we immediately became friends and we bonded. She went through a year or two after I did, down in Atlanta. She had a similar story. They were really hostile to her. I think Cherry had it harder than I did. She pushed against the grain the whole time.

I found out that they told her some things that were wrong and dangerous. We were working together on a few jobs, and she confided in me. “Listen” she said, “I think they’ve told me some shit that’s wrong.” She didn’t want to tell anyone because once you’re a journeyman you’re supposed to know everything. She told me some of the stuff, and I said, “You’re right. That’s not right what they told you. In fact, if you did it like that, it could possibly hurt you, cause a problem, damage some equipment, start a fire, or cause electrocution.”

They really fucked with her with some of the stuff. Over the years, there would be several things that she’d be doing, and I’d say, “What are you doing?” Cherry would say, “That’s how they showed me; that’s how they taught me.” They had told her wrong. I think they really tried to sabotage her apprenticeship, and to direct her in the wrong way. I appreciated working with her on that.

We worked together on a few jobs. Cherry was kind of claustrophobic. She didn’t like to be in crawl spaces. A lot of our work was either in an attic or in a crawl space. I would go in the crawl space, and she would go in the attic. Then, she’s up in the attic, and she’s tearing around, and I asked, “What’s wrong?” She said, “Oh, I don’t like all this insulation!” [Laughter] I said, “Look, you have to pick. You have to do something.”

We worked on the first Southern Women’s Music & Comedy Festival. [It was held in 1984 in the north Georgia mountains.] Cherry Omega, what a character! She was so charismatic. All the women loved her. I just loved watching her be an unashamed, unabashed person. Cherry was having such a big old time [enjoying herself].

I thought working the festivals was one of those bucket-list things, a glamorous job. No! [Laughter] Southern fest just about killed us. And then we worked the first Rhythm Fest, also in north Georgia, in 1990, and they just about killed us on that one, too. I’d gotten my belly full after working just two festivals. I realized that I could afford whatever the cost of the festival because they were working me way too hard for this $140.00 ticket.

We really had a lot of good fun together. It was the early 2000s when Cherry came back to union work. She had figured out how she could work fall, winter, spring, and then have time off during the summer. That way, she could go to all the women’s music festivals. I could tell you some Cherry Omega stories, but we’ll save that for the next time.

When work began to change, Cherry lost her house out there in Chamblee, Georgia. She loved that house. That’s when she moved up to SPIRAL, women’s land in Kentucky in the late 1990s, renting Cedar Heartwood‘s house while Cedar was away. I would see Cherry every six weeks or so because she would have to come down to Georgia to keep her unemployment active in Georgia. We were both big women, big-boned gals, you know, big, heavy gals. She had started losing weight, and she told me, “I’m working hard, working in the garden. I’m eating clean, you know.” That’s great, that’s all good. Then, the next six weeks, she’d come back, and she’d lost some more weight. She just kept getting thinner and thinner, and I knew something was wrong.

I was calling Mendy and others up in Asheville, asking them about Cherry, telling them that I was worried, you know, I was worried. When we finally did pin Cherry down and got her into Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, it was January 2004. Cherry passed away in June 2004.

It really impacted me. I was her Power of Attorney for her will. I did all the paperwork to get her retirement money from her health insurance, from her retirement fund, and all that shit. She was only 54. That was my job. I would run back and forth between Atlanta and Asheville. We had found her a place up there in Asheville while I’d go back and forth to Atlanta to shove papers under her nose. Unfortunately, I felt later like I missed a lot of really good time with her because I was too busy being busy with the business of her dying, instead of sitting and spending time with her. You know, talking.

Getting Clean and Sober

My drinking really escalated that next year. I was already a heavy drinker to start with. Something just happened then. I call it a moment of clarity. The reason Cherry O. had died was because she was in denial about her disease. I had an answer. I had an aunt back in Tennessee who was this big, powerful woman who took up a lot of space and went through husbands like tissue. I’m named after her. She’s the one who introduced me to vodka tonics. She would say, “They don’t make enough vodka for me and my niece.” She died from alcohol-related disease while I was in Birmingham.

I just sort of got it that if I continued to be in denial about my disease, it was going to kill me. So, I went into the rooms of AA [Alcoholics Anonymous program], and I picked up a white chip. It was June 6, 2006, making my quit date 6/6/6, which to me was the coolest thing. My sobriety day was 6/6/6. I thought I was such a badass.

I just sort of got it that if I continued to be in denial about my disease, it was going to kill me.

I did a little marijuana maintenance in that first year. I didn’t have a drink, but I had a little marijuana maintenance, as they called it. There were people in the program that said that’s just fine as long as you’re not drinking alcohol. Some people called it “California sober.”

I believe sobriety is out there for everybody. I think the gift of grace and clarity and sobriety is there. The luck or the gift or the true grace is those of us who get to take it in, to accept it. You know, there are people who don’t. It’s available to everyone, but I was the lucky one. I got it. I’ve watched a lot of people come and go, who didn’t get it. My brother didn’t get it. I lost him a couple of years ago to the disease of alcoholism.

I was working the steps of the program, working with a sponsor, going to the meetings, and I just felt like… what, I’m high! Right? I’m fucked up. I’m not sober. They were using clean versus sober. The semantics. I just felt like I was a hypocrite. I came clean to my sponsor, and she had me pick up another white chip. [In AA, you get a white chip when you begin the program, or when renew your commitment to stay sober.] My new sobriety date was June 12, 2007. I still argued with her about it. That is why my sobriety date changed. I did give my liver an extra year.

Starting a Band (Roxie Watson, now Just Roxie)

LL: I’m happy to be clean and sober. Right after that is when I started the band. It was one of those things on my bucket list. I’d always been involved in music, but I was kind of shy about singing. I had played around with a couple of bands. Once I got sober, it was one of those things. Again, this clarity about what I have always wanted to do. I’ve always loved music. I’ve always wanted to do music. I’ve always wanted to make music. I want to be involved with music somehow.

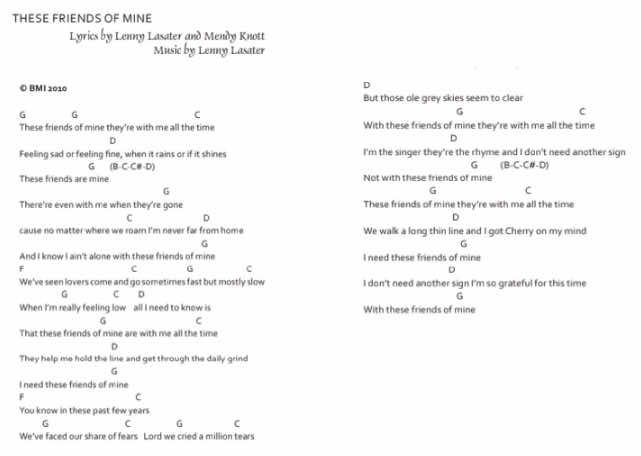

The Roxie Watson band evolved from that, and we’ve had a great run. We were a quintet, then we were a quartet. Now, there are three of us. First, we called ourselves Roxie Watson. Now, we’re “Just Roxie.” We’ve made about four records or CDs. I started writing songs. The first song I wrote was “These Friends of Mine.”

The lyrics and my story about it were in the Sinister Wisdom, vol. 124, Spring 2022. It is a song that I believe Cherry Omega sent me. I wrote down the rough draft of “These Friends of Mine” on a dry cleaner ticket. What I realized was that even though I was doing all that administrative work for Cherry, there were all these people around me who were supporting me to help keep me going. I realized that I couldn’t have done it on my own. “These Friends of Mine” came from Cherry, and it was dedicated to her. I even refer to her in the song. That one was on our very first record.

I think “Blue Creek #3” is the song that I wrote was on the next record. I had been talking about it when I worked in the coal mine, working the graveyard shift. We were doing a song called “Graveyard Shift,” and Bee Wee said, “You should write a song about your experiences.” That’s where “Blue Creek #3” came from. It’s about my time in the Jim Walter Blue Creek #3 mine. Those lyrics are in Sinister Wisdom, vol. 93, Summer of 2014.

MM: That was the first issue that the Herstory Project did for Sinister Wisdom, volume 93. Your song, “These Friends of Mine,” was in the last issue we did for Sinister Wisdom, volume 124.

LL: Wow! We published “Blue Creek #3” with the missing verse about kissing the girl in the dark. [Laughter]

MM: Yes, I love that. It’s good. And I love the Roxie Watson tapes that you sent me. I just love them so much for music in the car. They’re really good.

LL: The band is amazing. I mean, all the rest of the women in the band. It was five women, four women, now three. Heavy harmony. We three now were the primary singers all the way through. All of them are amazing musicians who have been in lots of other bands. I’d never been in a band before that. In our first biography, they all wrote the different names of the bands they’d been with, you know, and I wrote “Lenny Lasater Electrical” [Laughter].

I was so lucky to get to work with them. Now my band mates, Becky and Linda, are brilliant musicians. They’re great. We just had a show this past weekend at Eddie’s Attic, a show completely sold out! The crowd was screaming and cheering the whole time. I tell funny stories, and we do good music. It’s about 75% original and 25% clever covers. We’re “Americana-alt-country.” We used to use the term “alterna-grass” as opposed to bluegrass. It’s a gift of my sobriety to have the clarity, to be clear headed, becoming a dependable person, sober; and then, finding these people to start making music with. It’s continued, I guess, fifteen years or so now. One incarnation or another of Roxie has been around. (See JustRoxie.com)

MM: Yes, that’s so cool!

LL: It’s good, and I feel very happy, very blessed. The band nurtures that creative thing in me, and the music that I love. I love to sing, and I finally let my voice out. I have to say, I’m a pretty good singer.

MM: You blew me away. I thought, “Lenny sings?” I never knew that. Then I heard you, and I thought, “Oh, Lenny sings!” Yes, beautifully.

LL: [Laughter] Thank you. Singing harmony with Linda and Becky is a blessing and it’s brilliant. We blend so well together. I do the low, Linda, the high, and Becky, the middle. They both have gorgeous voices. Linda has that high, delicate voice. Sometimes it takes my breath away listening to Becky sing. She’s something.

MM: Are you writing songs, too?

LL: Writing songs. I need to get busy. We made an album with Just Roxie, the trio. We started it in spring of 2020. And we had a little something called COVID-19 happen, and we had to stop. A little over a year later, we came back into the studio. We did a kickstarter [crowd sourced fundraiser] then, and we finished it up a year later. We lost a whole year of performance. In November 2021, we had our CD released. We named it “We Missed You.” I need to send you a copy if you don’t have it.

I love the band. I love being in the band. I have so much fun, so much positive encouragement about singing and about my writing. I never really thought I was a writer. As I said, Mendy [Knott] is my cowriter. She is an amazing, brilliant, author, writer, songwriter, and screen writer. And her words are amazing. I love her words because they always elicit so much visual for me. I love working with her on song writing. We’ve collaborated on many songs that Roxie’s done over the years. She was here this past weekend for the show. [In Sinister Wisdom 124, Lenny credits Mendy Knott as cowriter of “These Friends of Mine.”]

It was a fun night. You know, we’ve been blessed to play the Bluebird Café in Nashville several times. What an accomplishment! That was a bucket list kind of thing. You know, I put it out to the universe. Is the Ryman Auditorium next?

[The Bluebird Café is legendary for the famous bands and singers who have performed there. Ryman Auditorium was the original home of the Grand Old Opry. Both performance halls are in Nashville, Tennessee.]

It’s been so much fun. And working for myself all these years has been a blessing. My dad was self-employed, and I saw the advantages of being the boss. I can take off when I want. Lenny Lasater Electrical. If I don’t work, I don’t get paid. Yet it gives me the opportunity to be in a band. I can have a band gig on Saturday night, and I can take off on Friday if we have to travel to the gig.

Being self-employed is a great thing. Although recently, I was threatening to retire. And I was thinking about changing the name from Lenny Lasater Electrical to “Old Lady Lectric Company.” [Laughter] The tag line was going to be: “If it’s not too high, if it’s not too hot, if it’s not too hard or too heavy—I’ll be right over.” I wasn’t sure if that would elicit a lot of confidence. A lot of friends have said that’s a great tag line. Of course, in Atlanta, that’s not too far. But I don’t climb on top of buildings anymore. I have a six-foot and a ten-foot, A-frame ladder. If I can’t work it off those ladders, I don’t do it.

I’ve been so blessed the last couple of years. There’s plenty of work that doesn’t bust up my knuckles, and that lets me use this [pointing to her head]. I do a lot of consulting with realtors to help houses get sold. We work the negotiating with buyers and sellers. We work with a lot of home owners associations. I worked strictly on referral all these years. I am kind of the grandmother. I hate that, but I am the “old lady electrician.” I’ve been doing it some forty years now. It turned out to be a pretty good trade. I don’t miss pharmacy. I like working with my hands. I like being able to fix stuff.

MM: You have to figure things out sometimes to stimulate your brain.

LL: Oh, yes. It’s something different all the time. I’m still learning and challenging myself. I’m learning new skills and stuff that I should have learned a long time ago. The electrical industry is so varied that there is a lot that I never encountered. There are so many things to experience in all these years. It’s been great. I feel like I’ve had a wonderful, blessed life.

Being out, being a proud, out, masculine of center, old butch… I call myself a courtly, Southern butch. Unapologetic. I got called “sir” forever. I don’t give a shit. I’m grateful I don’t have any gender dysphoria. I’m a woman. I’m a 100% USDA prime woman, lesbian, and old butch. I love beautiful, feminine women. Just about all of them. I’m happy, healthy, and approaching retirement. I’m still going to try to play the guitar a little, to make some songs, and to tell some stories. I’m grateful that our society has turned around where I feel as if I never have to hide who I am. I mean, I think for a minute there, it was kind of trendy to have a lesbian electrician.

Then again, the biases I encountered early on, I rarely run into anything like that now. I’m always out and open. I refer to my partner as “she.” It’s been really good to see how that has shifted over the years to be accepted, the inclusion of lesbians.

I call myself a courtly, Southern butch.

Unapologetic. I got called “sir” forever. I don’t give a shit.

They’ve been doing it forever, too. Most people I work with here in Atlanta are kind of a blue [blue as in “liberal“] area, for sure. Queer. Me being a lesbian. We don’t care. Even being an out, lesbian band. For a while, we never broadcast it. We didn’t want to be put into the niche of the gay band. We’re clear in our songs when talking about our partners and our women. The audience doesn’t care.

When I was with Kecia Cunningham, she was the first, openly gay, African American woman of color, and lesbian to be elected to the City Commission in the City of Decatur [Decatur, Georgia is adjacent to Atlanta]. I was the “First Butch of Decatur” for a while. That was really fun. She was later Vice Mayor. Decatur is another very accepting area. When we walked in with our heads held high, unlike Birmingham, unlike Augusta, what I experienced was that we were proud of who we were. We didn’t have any shame about who we were and what we were. We just walked in, and we were comfortable with ourselves, and they were comfortable with us. How hard is that? If you walk in with shame, with “I’m a second-class citizen, third class,” people are going to read that.

I want to say that I really appreciate being asked to do this. I am especially honored to be able to spend this time with you. You have always been someone I have admired. Your writing, your willingness. You were a front-line, out lesbian, again, in the trades. I know you went through a lot of the same shit that I did. And again, you are unapologetic. You walked right on in with the attitude of “I belong here.” I saw that behavior from you. That helped reinforce it in me. I fucking belong here.