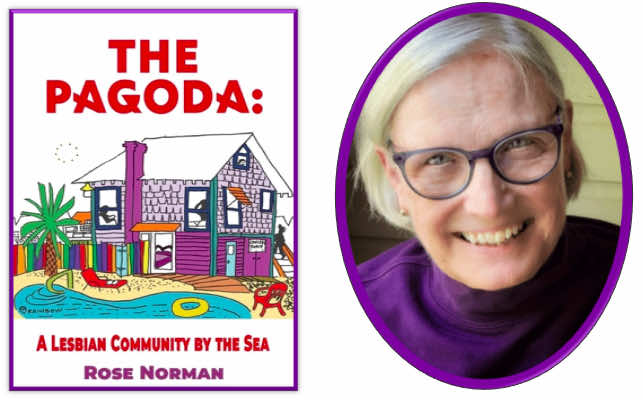

The Pagoda: A Lesbian Community by the Sea–Interview with the Book’s Author, Rose Norman

Interview on Zoom by Merril Mushroom on November 7, 2023

Merril Mushroom: This is Merril Mushroom interviewing Rose Norman about her book about the Pagoda, a lesbian residential community and cultural center in St. Augustine, Florida, active from 1977 to 1999. Rose, your book on the Pagoda was just released. How do you feel about that?

Rose Norman: Wonderful! I interviewed nearly fifty people, who all got copies. So far, the feedback has been good. Sinister Wisdom, my publisher, is doing a Zoom release event on January 23, 2024, that will be recorded and available on their website, which has a page for the book: sinisterwisdom.org/pagoda. They are doing a wonderful job of distributing and marketing the book. I could not ask for more.

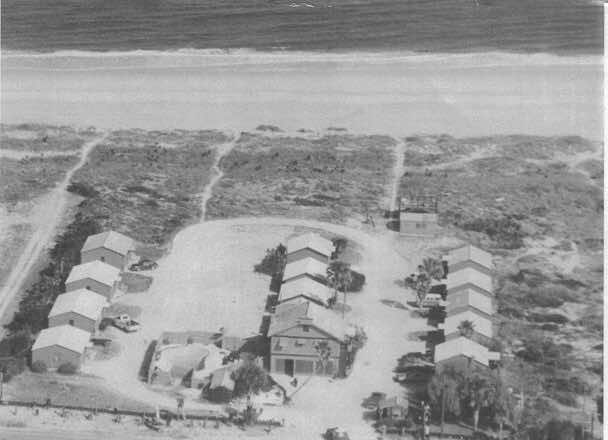

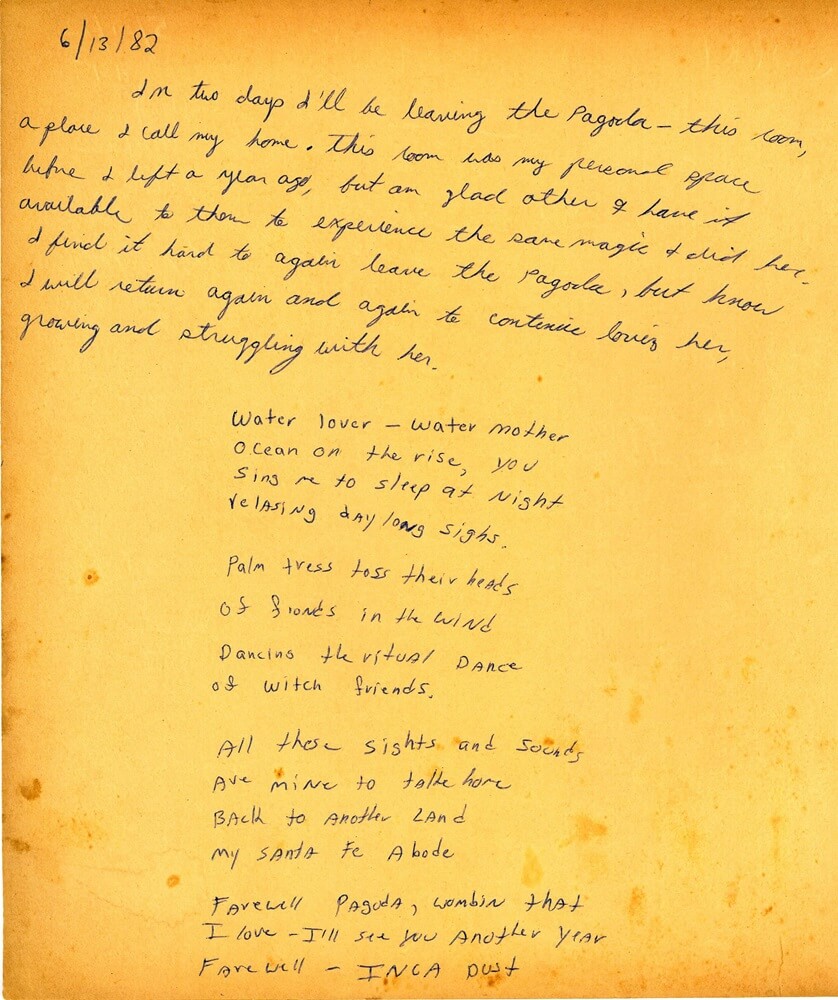

On the right is an aerial view of the Pagoda Motel as it looked in the 1970s, when the four members of a St. Augustine dance troupe bought the middle row of cottages and leased the big building in the center as their dance theatre. Florida State Road A1A runs north and south in front of the buildings. The ocean is just east of the cottages. The left aerial view is a 1948 picture of the lot across State Road A1A from what became the Pagoda Motel. The area was not well developed at that time and was accessed by a drawbridge. A new bridge built in 1995 emptied its traffic where that house across the street is, creating traffic problems for the Pagoda.

MM: You have several other Zooms scheduled about the Pagoda, is that so?

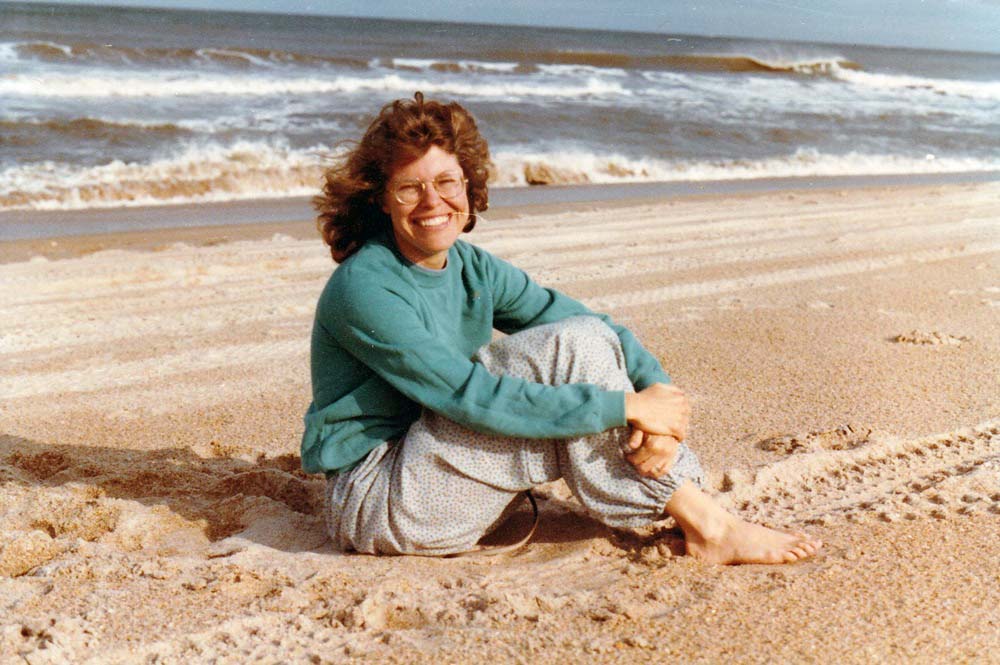

RN: There’s “Pagoda Memories on Film,” a February Zoom with Emily Greene, who contributed most of the photographs used in the book. Emily has a collection of over 500 photographs from the years that she lived at the Pagoda, about ten years, starting in 1978 and 1979. She sold her Pagoda cottage in 1992, but maintained her connection to the community. In the 1990s, she got a video camera, and she started videotaping things like parties at the Pagoda as well as events elsewhere. She’s going to be doing a Sinister Wisdom Zoom about her photo and video collection, which encompasses fifty videos (twenty at the Pagoda) that have been digitized and archived by the Lesbian Home Movie Project. For that program, Emily will be joined by Sharon Thompson, who is with the Lesbian Home Movie Project.

MM: How do you feel about the book finally coming out, after all this time? Do you have a starting date from when you first knew that you were going to write this book?

RN: I don’t remember when I decided to write the book, but we were doing the interviews for Landykes of the South, which was our second special issue of Sinister Wisdom. You and I, and a crowd of others, have been working since 2009 on a much larger project: the Southern Lesbian Feminist Activist Herstory Project. In 2014, we started publishing in Sinister Wisdom what we were doing with the project. Landykes of the South was a collection of stories for Sinister Wisdom about women’s land groups. I wanted to write about the Pagoda for that issue.

Emily Greene was still living at Alapine then. Alapine is a lesbian community about seventy miles from where I live in Huntsville, Alabama. That’s extreme north Alabama. I knew that women from the Pagoda lived at Alapine, and that’s about it. My knowledge of the Pagoda was all secondhand and sketchy. Friends of mine had been there in the 1990s, when the Pagoda was still a going concern. I wasn’t really clear about what the Pagoda was. Women that I interviewed in Gainesville, Florida, in 2012, had referred to it as very different from the women’s land near Gainesville. From this, I inferred that there was some kind of a shadow over it. Something had happened there, but I wasn’t sure what. Emily offered to arrange a group interview at Alapine. I figured that I would write a story based on that group interview.

The interview that Emily and others had arranged brought together six women who had at one time lived at the Pagoda, or who had been strongly connected to it, and who were then living at Alapine. I went to Alapine for the weekend. I was just bowled over by the story! It was way more than I had imagined! I had no idea that there was a residential community with twelve cottages and a duplex, owned and lived in by lesbians, or that the community had a cultural center that was active for twenty-two years, or what had led to any of it: how it started, how it ended. I knew none of that. I found myself with an immense amount of information that led me to interviewing more women about their Pagoda experience.

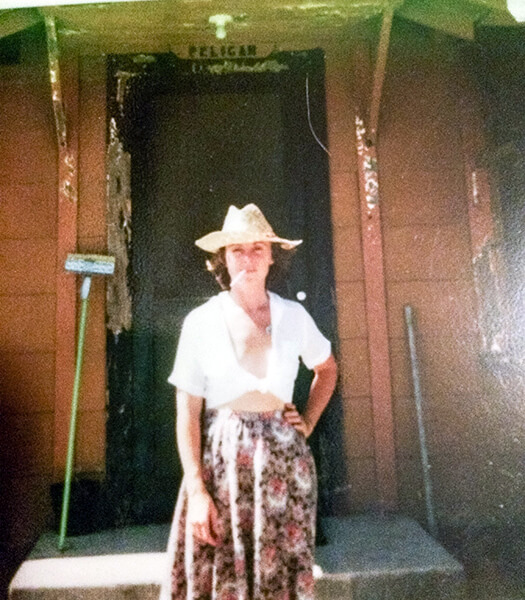

I still thought I was going to write one story for Landykes of the South when I went back to Florida in 2013, ten years ago. That’s when I met Rainbow Williams, the artist who drew several of the illustrations that we used in the book, including her drawing that we colored for the cover. Rainbow had a ton of material about the Pagoda, and I spent almost all day with her. She took me out to the beach, and she showed me the Pagoda cottages for the first time, including her own cottage, which she had owned for twenty-five years, and which she had sold by chance the day before I met her.

The Pagoda was sort of like a wave that swept over me, taking me in its current. Before long, I had so much interview material that I realized it had to be a book. Not only that. I couldn’t write a short version of the story! I was so full of the Pagoda that I could not get the story down to the 1500 words we needed for the collection of Landyke stories. I had so much more to say. You, Merril, you wrote the Pagoda story for Landykes of the South (2015), and you wrote another one about the theatre at the Pagoda for the next issue we did, Lesbianima Rising (2017). That story is about their first few years when they regularly produced feminist plays and even had a lesbian playwright in residence. The first Pagoda story that I wrote for Sinister Wisdom came out in our last issue, Deeply Held Beliefs (2022). There I told the story of Pagoda: temple of Love, the Goddess church that was headquartered there.

MM: Most of your initial information came from talking to people and hearing their stories. One person referred you to another person, and it all just happened in your life like that, correct?

RN: I’d say that for the first three years, it was almost all oral testimony from interviews. People might have a scrap of this or a scrap of that until 2016. Then, I finally tracked down Rena Carney, who had kept every single piece of paper she had to do with the Pagoda, especially the newsletters that came out with financial reports.

I thought it was going to be programs from events, and there were some of those. But those newsletters were a bonus. They were full of detailed information about what Pagoda women did every month: who did what, what it cost, and the problems they were having. I read and took notes from monthly newsletters spanning over ten years. It was quite a job.

From those newsletters, I created a timeline that is now about 150 pages. I just keep adding to that timeline to make it easy to look up events and people.

Maybe that was when I knew I could write the book. Getting there was really thanks to Rainbow Williams. Rena was helping Rainbow, who was over eighty years old and was having difficulty with her computer. Rena helped Rainbow edit the very long interview notes that I had sent Rainbow. Rainbow eventually convinced Rena that I was okay, that she could talk to me, and that maybe she could do an interview with me.

In fact, the first time I called Rena, she didn’t want to do the interview. She wanted to interview me about it. However, she invited me to come down to stay at her Pagoda cottage, and to look at all her documents. Once Rena was clear that I could be trusted, she opened up what became a huge treasure trove of documents about the Pagoda.

I can’t overemphasize how extremely well-documented the Pagoda is. Rena’s collection was joined later by boxes and boxes of records from the women living at Alapine. This book is only the beginning of what could be written based on the documentation that’s out there.

MM: Do you intend to write more based on this documentation?

RN: Possibly. I wrote thirty-six profiles of Pagoda women that did not make it into the book, which had to be cut a lot to be a manageable size. I may try to publish those as Pagoda Women or something like that.

As far as writing another book about the Pagoda itself, I think some graduate student needs to come along. There’s plenty of material for a more academic analysis of what they accomplished.

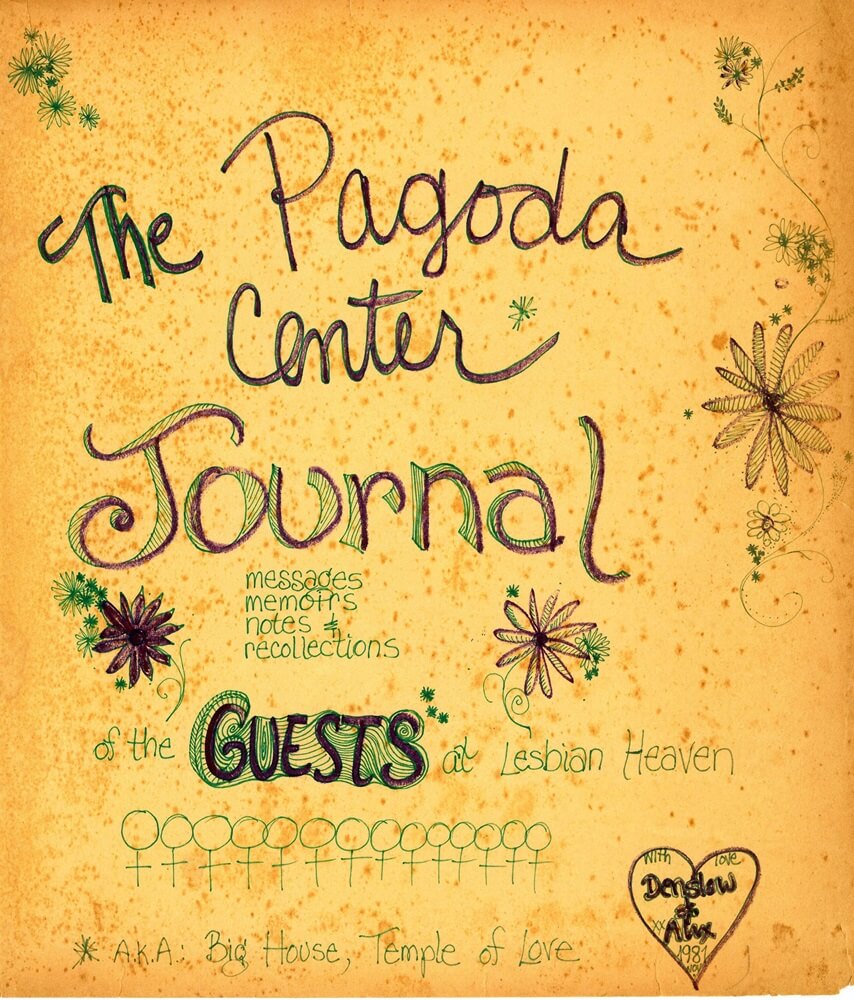

It was probably in 2018 when the people at Alapine unearthed over five, banker-sized boxes of Pagoda documents. Unbelievable stuff! I already had the newsletters and monthly financial reports that Rena had, but this added more of that plus copies of deeds on every cottage. There were also scores of letters that people had written to the Pagoda, and two Pagoda guest books in which people had written and doodled. I was particularly interested in the thick folders full of letters that women wrote them about several controversial topics that Pagoda women had handled and resolved. All of this material had been in storage, forgotten. Or maybe it was too difficult to retrieve from a trailer that was in bad condition.

MM: What were those controversies?

RN: The first big one one was lesbian battering. That was 1989. I don’t identify the person in the book, and I don’t want to say it here, either. One of the people that lived at the Pagoda accused a previous partner from some years back of having battered her. The accused batterer was a supporter of, and thus a regular donator to, the Pagoda. Some Pagoda women wanted to ban anybody accused of battering from being there, which caused a huge controversy. The community of residents and supporters were never able to resolve how to do it. Well, actually, Rainbow and others did propose a written policy that a lot of women wanted the Pagoda to establish. But they couldn’t agree on it.

Lesbian battering was a topic that was being written about in lesbian feminist publications at that time because all the literature around battering then was based on heterosexual relationships, mostly about men beating up women.

MM: What was the disagreement?

RN: How to treat the person who had been accused. Often the person who was accused would deny the accusation. The first woman to be accused wrote a very persuasive, five-page, typed letter in response to the accusation. It seemed to me that if there was any battering going on, it was mutual. The woman who was accused ultimately wrote that she chose to withdraw, and that she would no longer be part of the Pagoda.

Lesbian battering was a topic that was being written about in lesbian feminist publications at that time because all the literature around battering then was based on heterosexual relationships, mostly about men beating up women. Of course, as you know, friends of yours were physically beaten up by lesbian partners. It’s not that it didn’t happen. It’s just that it’s more complicated. Relationships between women are different from relationships between women and men. There is a different cultural dimension, a different power differential.

It was much easier to ban men, period, than to ban women. The residential community eventually decided that they would handle it themselves within the community. They would not have a written policy. If they knew that somebody who was accused of battering was going to be there, they would work together to provide safe space for the woman who had been battered. That was how they dealt with it.

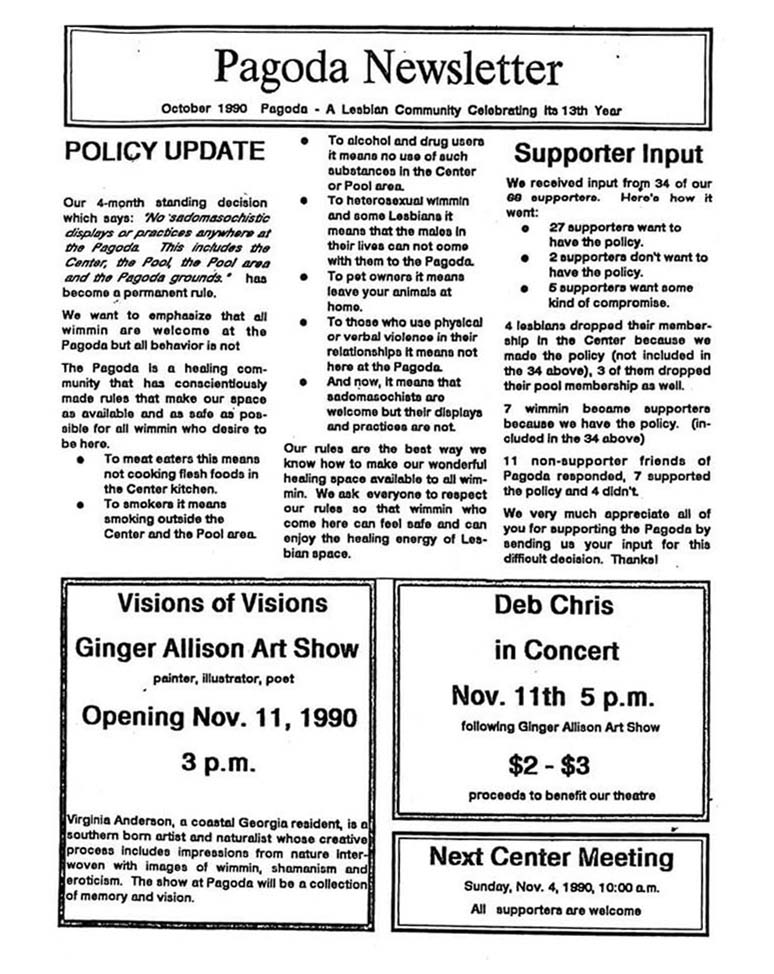

On the heels of that controversy came the sadomasochism debates. St. Augustine is about an hour and a half from Gainesville, and many Gainesville lesbians came to the Pagoda on weekends. A lot of the Gainesville dykes were into sadomasochistic (SM) role playing at that time. They had piercings in their nipples and their vulvas. They wore chains and things like that. All that was a trigger for residents and others who had suffered sexual and physical abuse. It became a cause célèbre when a woman left a bloody hand-print in the guestbook. The bloody hand-print was from a woman who had been fisting another woman during her menstrual period. It was not blood from violence or cutting.

That bloody hand just raised a massive ruckus. They came up with a written policy within days. Then, they had a discussion period lasting several months, during which people wrote letter after letter on both sides of this. They wound up voting.

On the other policy, about the lesbian battering, they kept trying to come to consensus, which was their usual practice. However, on the SM policy, they voted. The vote was overwhelmingly in support of the policy, which said, “No SM behavior anywhere, anytime, on the Pagoda property.” This policy did not include inside the cottages. It concerned behavior inside the guest house and outside on the property.

MM: Did that hold, or did they need more discussion and more back and forth?

RN: They lost supporters. People stopped coming. People who practiced SM felt unwelcome, and their friends who did not practice SM stopped coming, in support of the SM dykes. The Pagoda lost a lot of their Gainesville supporters. I think that maybe that was the beginning of the end, possibly because of the way the vote was handled. At that time, most of the money that came in to support paying the mortgage and other expenses of the cultural center was coming in from non-residents. The people who were paying $10 or more monthly were supporters. That donation allowed them to stay at the Center for free when they came. As it turned out, they counted non-resident supporter votes as one collective vote. There was a letter from women who were withdrawing their support, explaining that they understood that all the non-resident supporters who voted got only one vote among them, whereas the cottage owners and other residents each got their own vote.

Before that, Pagoda women had fostered the feeling that if you were a supporter, you were part of the community. They didn’t make a big distinction between supporters and residents. There had never been a case where only residents got to vote. There might have been cases where only residents were present to vote. But this was a vote that was carried out by mail, and they collected a lot of votes.

MM: They only got one vote? Was it the majority rules? Like the electors in our country here?

RN: It was a little bit like the electoral college: the supporters were one state, and the residents were separate states. There were sixteen residents at that time, and sixty paying supporters. It looked to me as if the great majority of non-resident Pagoda supporters also supported the policy, so majority ruled any way you counted it, but some non-residents didn’t like how the counting went.

MM: How did that happen? How many instances at Pagoda did that all come up?

RN: That happened in 1990, right on the heels of that lesbian battering controversy. There were many women who connected the two practices, battering and SM. Many were treating SM role playing as battering.

MM: Were there more cases of battering, or did that one kind of spread out?

RN: There were more. I only read one letter from a woman who was defending herself against the accusation. There was another letter from a woman protesting that her current partner was being accused of battering, and it wasn’t true. I also heard oral testimony about it, women talking off the record. One woman reported that women would come to her to complain about a partner battering them, either physically or emotionally. She had to finally say, “We aren’t going to keep this a secret. Don’t tell me this stuff, and then, expect me to keep it a secret. If this is happening, you need to address it.” It seems to have been associated with alcoholism, something women were doing when they got drunk. But I never interviewed anybody who had personally been accused of battering.

MM: And what about alcoholism? Did they have any issues around that?

RN: They banned alcohol from the Center early on. They originally had a bar in the cultural center where they sold beer and wine. It was called The Backstage Bar. That was in 1977 to 1978. Somewhere around in there, they banned alcohol from anywhere in the Center although you could have it in the Center refrigerator if it was kept in a paper bag. Of course, it wasn’t banned from the cottages. Women could have alcohol in their cottages. Early on, all they were renting were cottages. They had a lot of empty cottages that they rented. The only people that were living in the Center were workers, people who were working for the Pagoda.

MM: How did they deal with drinking and drunken behavior there if people would drink where they lived?

They had at least two professional counselors that lived there.

RN: There is almost no mention of drunken behavior in the paper record, other than drunk men who would occasionally harass the residents. I don’t remember it coming up as a problem. Somebody told me one time that the reason they closed The Backstage Bar was because it was losing money. Now how does a bar lose money? It loses money because somebody who is associated with it is drinking or giving away the supplies. That was when they banned alcohol. It wasn’t because of violence associated with alcohol, not that I could tell. They were coming to the understanding that alcoholism was a problem in the lesbian community. One way they could address that was to make the Pagoda safe space for women in recovery. They banned meat, too. The Center became a vegetarian-only space.

MM: How did that go over?

RN: Well, a lot of lesbians were vegetarian back then. But I’m sure there were complaints.

MM: There are so many dykes who say, “I need my meat.” What about mental health issues? Was there any support, or mention of it? Or was it ignored? Or was it just not a problem at all?

RN: Oh, it was a problem. They had at least two professional counselors that lived there. For the book, Emily Greene was the one who agreed to let me include what she had to say about a breakdown she had there early on. She was working as Director of Nursing at a nursing home, and things were not going well at work. They were understaffed and underpaid, all that. She had also had a romantic breakup. She had some kind of a breakdown. I quote her in the book describing how they handled it. They got her mother and sister to come down from Massachusetts to be with her; and the community got Emily into counseling. Emily attributes what they did at the Pagoda to her fully recovering and becoming a more confident person. Other people were struggling with mental health issues, too.

MM: Did it become a community issue, like the battering and the SM?

RN: It wasn’t a controversy that people talked about or wrote letters about. It was something that they dealt with. There were a couple of occasions when the community was taking turns on a suicide watch with a resident. There were no suicides at the Pagoda, but there were suicide watches. Some of the research on intentional communities says that sometimes people with mental health issues are drawn to that kind of community, maybe because of the feeling of community support. One of the main points of the book is that the Pagoda was a healing place to be.

MM: Also the acceptance: “Oh, I’ll go there because I can be who I am; and maybe they’ll help me, and maybe they won’t help me.” When you were gathering your material and doing your interviews, what did you find to be the most difficult part?

RN: The material was overwhelming. There was so much! And of course people had different versions of events. You remember events differently. There were quite a few differences of opinion about things that happened there. I struggled for a long time with how to get everybody’s point of view respected without hurting anybody else. One person said I sugarcoated the hard stuff. I don’t think I sugarcoated it. Let’s say that I had to draw on a lot of diplomacy.

MM: Like what?

RN: Well, like the bloody hand. Once I wrote a whole chapter about the bloody hand, with names. I read that at a Dykewriters gathering, and the biggest response was, “You used their names!”

MM: It sounds as if you were absolutely a Pagoda magnet. All of this information, documents, people, and interviews just kind of stuck to you, and there you were with all of it. Did you ever have any trouble getting stuff that you really needed?

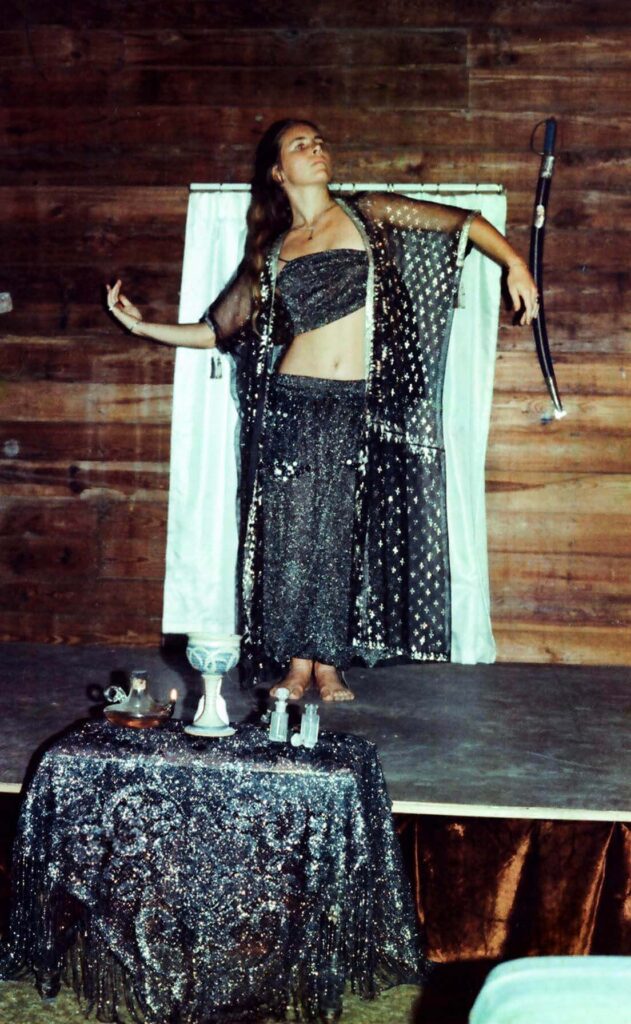

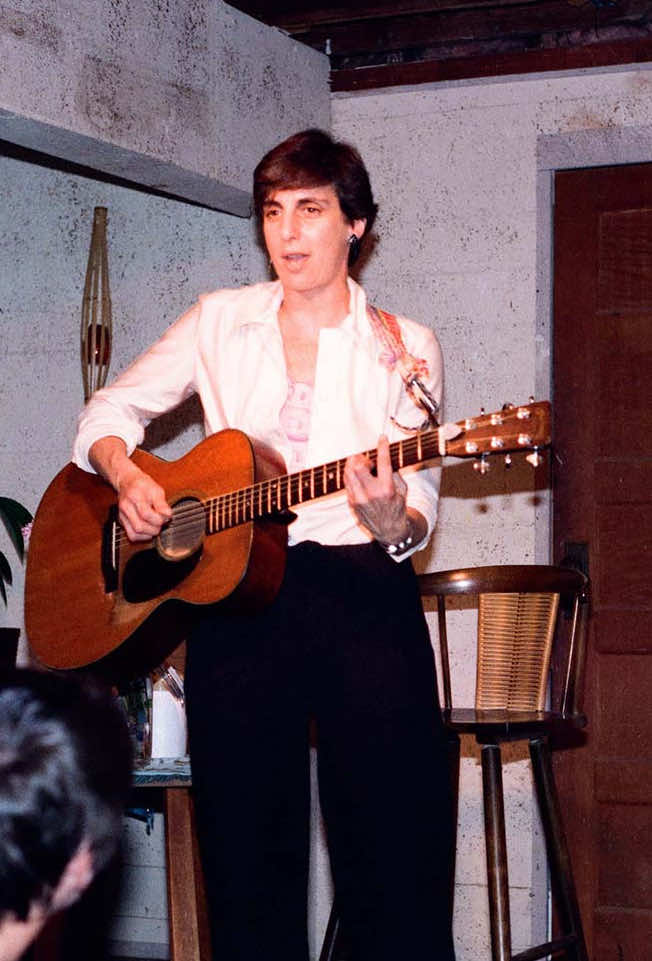

RN: Early on, I was not getting the documentation that I wanted. For a long time, I thought that Rena was the only one who held on to it. I didn’t know for years about those five boxes of documents that I arranged to be archived at the University of Florida. Then the videotapes turned up, first from Rainbow Williams, and then from Emily Greene. In fact, Rainbow mostly had copies of Emily’s videotapes. Emily has several with Morgana dancing and Flash Silvermoon playing, either the drums or keyboard. In one, Flash is playing a song she wrote for Morgana to dance to. Emily has also put together a video combining her still pictures with clips from her videos.

MM: In Emily’s videos, were there people talking about stuff and discussing stuff, or was it mostly people performing? Any general conversation with each other?

RN: It was mostly people performing. I can’t remember any discussion. Emily did videotape that first group interview that I did at Alapine. That video is archived, and I think that they have releases from everybody that was in it. The audio from that is online at Duke. You can listen to that original interview. There were six people being interviewed, and it’s a two-hour interview.

MM: I can’t wait for the Sinister Wisdom Zoom. What surprised you while you were doing your research?

RN: The whole thing was just extraordinary. It’s unbelievable that they pulled that off. I mean, an incorporated, feminist church just landed in their lap, and they turned the project into a community-supported cultural center with regular concerts by lesbian icons like Alix Dobkin.

MM: Tell about Pagoda: temple of Love.

RN: In Florida in 1978, which would be the year after the Pagoda started, some National Organization for Women (NOW) women, led by Toni Head, decided that feminists ought to have the same tax-exempt status for sharing their religious or spiritual beliefs as churches did. She incorporated The Mother Church in Florida as a nonprofit church, and she started doing a newsletter for it. She was in the process of filing for tax-exempt status for it when she published an article about the church, called “Changing the Hymns to Hers,” explaining what motivated her to start a feminist church. Toni Head was a feminist and not a lesbian. One of the women at the Pagoda, Lavender, read the story in Heresies, a feminist journal. Lavender wrote to Toni Head in care of the journal, asking how the Pagoda could participate. Toni wrote her right back asking her to help them get tax-exempt status, 501(c)(3). Lavender was a lawyer, so that was right up her alley.

The following March, in 1979, Toni handed the whole thing over to the Pagoda women. She could see that they could take it further than she could, since they were very involved with Wiccan feminist spirituality, whereas she was mostly into politics. In June, the Pagoda women filled out the paperwork to replace the board of the Mother Church with Pagoda women, and to rewrite the bylaws to make it a Goddess church. The Mother Church had been more interested in reproductive rights. That November, their tax exempt paperwork was approved.

A group of lesbians had already pooled funds to get a shared mortgage that let them buy the building that would become their cultural center. In 1980, that group turned the property over to the church, which by then, had changed the name from The Mother Church to Pagoda: temple of Love. From then on, they did not have to pay real estate tax on the cultural center building and they qualified for a bulk rate permit for postage, very important in those times before there was the Internet. Now all those $10 and $20 donations were tax exempt, just as Toni Head had envisioned.

This was, in fact, the second incorporated, tax-exempt Goddess church in this country, the first being Z Budapest’s Sisterhood of Wicca. There have been others since then. They were quite serious about the church element, too. They had ceremonies celebrating all the holy days of Earth-based religions. Morgana was the undisputed spiritual leader although she never called herself a high priestess or a “high anything,” in her words.

MM: What was the place of the Pagoda in the lesbian culture and community movements of the twentieth century? How did the Pagoda fit in with all that was going on?

RN: For the most part, the Pagoda was flying under the radar. I barely knew about it at all, even though I had friends that had gone there. They did buy ads in Gaia’s Guide and in the magazine, Lesbian Connection. Their cultural center was small. The theatre seated fifty. They had four bedrooms, including the attic, which was very popular because of the ocean view, even though it was accessed by a ladder and had no bathroom. They also rented sleep space in the dressing room behind the stage. They called it the Cave, and you can see the door in many pictures of performers. It was well known on the women’s music circuit. Occasionally, as when they had those controversies, the women who were involved wrote to the Lesbian Connection and to other national publications about what was going on at the Pagoda. An interview with Morgana and Elethia appeared in the book Lesbian Land (1985), the first collection of interviews with many women’s land groups.

MM: Joyce [Joyce Cheney, author of Lesbian Land] stayed at my home while she was on her trip around to do her interviews. She was a neat woman.

RN: Joyce Cheney also stayed at the Pagoda when the editors were putting the book Lesbian Land together. It was published by WordWeavers, owned by Landykes Nett Hart and Lee Lanning.

MM: I know a lot of people visited the Pagoda, and lived at the Pagoda. Did anybody go away from there and want to do something like the theatre, or something in the greater community? Were they role models for anybody that you know about?

RN: Often people who went to the Pagoda also went down to Sugarloaf, which is a women’s land community in the Florida Keys. There was a strong connection between Sugarloaf, founded in 1976, and the Pagoda, founded in 1977. Neither began as women’s land groups.

Sometimes, women went from the Pagoda to live in other land groups. Early Pagoda resident Laura Folk talks about going to Arf in New Mexico. She lived in a tent at Arf for a year. Another woman I interviewed had helped found two heterosexual, intentional communities in Vermont. When she came out as a lesbian, she divorced her husband and eventually wound up at the Pagoda for a year or so. The Pagoda turned out to be the last intentional community she lived in. She gave up on intentional communities after that. I’m not aware of any intentional communities started on the model of the Pagoda. Alapine was founded by Pagoda founders, and they used what they had learned at the Pagoda to found a very different kind of women’s community. I often asked the question, are you aware of any other places like the Pagoda, where there is both a cultural center and a residential community with a guest house? Nobody could think of one that was quite like that.

M: What do you think the place of the Pagoda is today, in Herstory?

RN: I see it as a microcosm of what was going on nationally in the late twentieth century. Many of the issues that came up at the Pagoda—S&M role playing, lesbian battering—were being explored in other places, and being discussed in national publications. Separatism is probably the most complicated issue they dealt with, although there was general agreement with the women-only policy. Women-only spaces were being explored in various ways around the country. The Pagoda was in some respects lesbian separatist in that only lesbians could buy one of those Pagoda cottages. However, any woman could stay at the cultural center, and they could bring children, just not boy children. They could bring boy children to the cottages, but not to the cultural center.

MM: Were boys under a certain age allowed?

RN: No boy child was allowed in the center. That was an issue I talk about a little in one of the chapters. The place of boy children was one of the controversial issues in lesbian circles everywhere in those years. Many lesbians had boy children. They’d have to get a babysitter before they could go to lots of events, and that wasn’t fair. One couple who had recently had a boy baby (very common with artificial insemination) got the policy mixed up and arrived thinking they could stay in the cultural center. The Pagoda women found them space in a cottage, but there were bad feelings about what happened.

Separatism had its value at that time. Getting away from patriarchal culture, at least as manifested by men, was valuable to women for healing, for feeling valued as women, and especially for feeling valued as lesbians. At the Pagoda, being lesbian was the norm, and that felt wonderful! It just didn’t have a long shelf life, as far as I can tell. There is a lot about living in community that is hard.

MM: Yes, it is hard! How do you think today’s youth culture would look at it? What place do you think sociologically the whole herstory of the Pagoda would have today with the youth culture?

RN: I know some young lesbians who wish that they had been around then because it looks as if it would have been so much fun, exciting and with so many possibilities. Getting that history on the record adds a few more facets to it than appear on the surface. What they accomplished was truly remarkable. From the outside, it looks like, “Oh, they must have had money,” or “These must have been trust fund women doing all this.” But they weren’t! Not one of those women that I interviewed would admit to a trust fund. Some were able to borrow a cottage down payment from a relative. Morgana sold her truck, and Emily Greene sold a life insurance policy her parents had bought for her. Most residents had full-time work elsewhere, where they were closeted, as Emily was at that nursing home. Rena always had a full-time professional job while volunteering most of her free time to producing and performing in theatrical events at the Pagoda Playhouse.

There were residents whose families were well-off. Some residents were able to earn a livelihood from working at the Pagoda, and from taking outside jobs here and there. There was a certain downward mobility that you only get with people who started out with plenty, and who can be satisfied living in a tiny cottage without a lot of creature comforts. Especially if you’re on a beach.

They had a terrific location when they started out. There were no houses between them and the beach, which meant that the weather was phenomenal, that breeze coming from the beach. Even today, when there are houses, it takes less than two minutes to walk down to the water. And it’s wonderful.

MM: But you can get to the water. Miami Beach, forget it; it’s like a solid wall of concrete. Do you think that the Pagoda, the way it’s presented and remembered, has been romanticized?

RN: I don’t think people remember it.

MM: They will now.

RN: They will, yes. When I was doing research in the academic literature about separatism and about women’s land, I was amazed at how little there was. Really, only one article in an academic book, reprinted with some revisions in another collection. It was pretty much getting erased. Some of what I found was very inaccurate.

MM: Does that have anything to do with the fact that it’s in the South?

RN: It could. And they kept a low profile. They marched and took a big banner that said “Pagoda” to the lesbian and gay marches on Washington, D.C., but they didn’t march in St. Augustine. They weren’t trying to draw attention to themselves in Florida. And they did get a certain amount of harassment from teenage boys who would drive through there, hollering “cunt,” and other slurs. Not that much.

I had to ask about harassment. Nobody brought it up. It wasn’t something they had to deal with very much. And that was partly by keeping a low profile.

MM: What do you think is the most important thing about the Pagoda that you would want for people to know today?

RN: It’s a manifestation of a dream. There’s something encouraging about seeing people following a dream. As the story unfolds, people peel off and leave because the dream was not entirely shared. They were people who were trying to follow their bliss. For a while it worked. They got the chance to experience a dream, and we don’t have enough stories about that. They had sacrifices. These people worked hard to make their dream a reality. And it wasn’t as if they had big bucks behind them. They were doing it with lots of donations and lots of hard work.

MM: Their picks and their shovels. Which I think is also really, really important. Do you think people, not just lesbians, would look at the story of the Pagoda and find it interesting and meaningful to them?

RN: I think it will interest feminist women generally, especially anybody interested in women’s studies. I can see it being assigned reading in a women’s studies class because there’s not that much out there about the experiences of the separatist women’s communities. Some women in Oregon have written memoirs about it, and there is a very good study of the Southern Oregon Women’s Community by Laverne Gagehabib and Barbara Summerhawk, Circles of Power: Shifting Dynamics in a Lesbian-Centered Community (New Victoria, 2001). My book is another close-up study of a feminist separatist community from an academic perspective. Most of the books about these communities are memoirs.

Two memoirs I recommend are Country Lesbians and Weeding at Dawn. Country Lesbians: The Story of the WomanShare Collective (Grants Pass, OR: WomanShare Books, 1976) tells the story of five lesbians living on twenty-three acres of land in southern Oregon, a state with a dozen or more lesbian land groups. Hawk Madrone’s Weeding at Dawn: A Lesbian Country Life (New York: Alice Street Editions, 2000) is the beautifully written story of Madrone’s experiences at Fly Away Home, another long-lasting lesbian land group in southern Oregon, forty acres bought in 1976 and still occupied by Madrone and Bethroot Gwynne, though in separate dwellings (they were never a couple).

The Pagoda was different from most women’s land communities in being relatively urban and on a small plot of land, less than two acres.

MM: How would one get it out there into women’s studies programs? Are there women’s studies reviewers?

RN: That’s what we’re working on now: promoting the book. The National Women’s Studies Association has an annual conference where Sinister Wisdom has a book exhibit. There’s also an email discussion group of women’s studies directors, and I still subscribe to it. I posted a “new book” message there.

MM: Rose, how did your work on the Pagoda book change your life? Or did it?

RN: As you know, the Pagoda book came out of the larger project of collecting stories of lesbian-feminist activism in the South. That project has changed my life. I started interviewing people two years after I retired from college teaching. It’s the best research project ever. It’s given me useful work and friends, and I don’t have to worry about publishing in academic journals. We’ve got it all set up to archive our interviews at Duke, we’ve got a team of women working on it, plus the Sinister Wisdom connection. Early on, we began publishing stories in Sinister Wisdom from our interviews, a total of six special issues that you and I (and others) have edited since 2014.

I want to add that Sinister Wisdom has been enormously supportive of the Pagoda project from the beginning. The editor, Julie Enszer (who has just finished publishing her fiftieth Sinister Wisdom issue) gave me very professional advice about shaping the book for publication. She read and commented on three drafts of the book, and Sinister Wisdom paid for professional copyediting and professional indexing. All that, and the book will go to all 1200 subscribers. The first printing was about 2000 copies. That is unheard of with an academic press or even another feminist press.

MM: What else do you want to say about the Pagoda?

RN: We haven’t said much about the Pagoda today. A lot of people, when they hear that I’m writing about the Pagoda, wonder if anything is still there. I’ve spent a lot of time down there in these last few years. Rena Carney let me stay at her Pagoda cottage quite a bit, and I’ve rented another Pagoda cottage to stay there for months at a time. There are twelve cottages, a duplex and the two-story building that the original owner, Shorty Rees, built as his home. Rees built all the cottages himself in the 1930s and ‘40s. He called it Rees’ Seashore Cottages and rented by the week or month. In 1970, he sold it to a couple who turned it into a motel and built a swimming pool next to the two-story house, which became the Pagoda cultural center.

The original women’s Pagoda was the first four cottages right behind the cultural center. Four women bought those cottages and leased the two-story building, which they turned into a theatre and lived in themselves. Almost immediately, four more cottages and the duplex came up for sale. Those other four cottages face the first four cottages. So you’ve got eight cottages and a duplex and this big house. Within two years, lesbians sharing several mortgages owned all that. It stayed that way until 1988, when lesbians bought the rest of the property [that shown in the aerial view at the beginning of this interview]. Of the eight original cottages, six are still owned by lesbians. The cultural center and the duplex next to it are now owned by men who turned them into vacation rentals.

MM: Are there individuals living individually and not in community?

RN: That’s right.

MM: What kind of physical condition are those buildings that are so old?

RN: Very good.

MM: Oh, how come? With the salt water in the air and everything eating at it?

RN: From what I’ve seen, the people who own them take good care of them, Rena has put a lot into hers. Hers is probably the most remodeled. She had a screened porch that she turned into a TV room, which has a sunroof on top of it with a spiral staircase. She has hardwood floors (before they were linoleum) and central heat and air. All of that was done in the last twenty years.

MM: That’s lasted pretty well.

RN: One cottage, not one of those owned by lesbians, was neglected for a while. They’ve recently done a whole lot of improvements to it. I would say that the owners are really taking care of them. The cottage that I rented is owned by lesbians who rent only to lesbians. It’s very basic. I mean by that, the kitchen has a toaster oven and two gas burners (laughter). It has two bedrooms, and it is in very good shape.

MM: What kind of development has moved in on them?

RN: There are houses and new hotels everywhere, including all up and down the beach. There are big, two-story houses between the cottages and the ocean. Even from Rena’s roof you can’t see the ocean except a little bit between those big, two-story houses. There’s also a really good Publix grocery store that’s a three-minute walk from the door of cottage seven. It’s wonderful not to have to take the car out to get groceries. There’s still a parking problem. It’s very hard to park your car. At cottage seven, just getting the car in the driveway is a feat. You really need that backup mirror.

MM: Did it used to be that hard?

RN: I think parking has always been a problem there. The cottages are very close together, and there’s not much room between them. You know, it was a motel. The road between the two rows of cottages is more of a driveway than a road or street.

MM: What’s the life for you when you go down to stay there, with everything that you’ve done, with everything that you know about it?

RN: It’s wonderful being so close to the beach, but I don’t know that there’s a feeling of what it was like then. That’s partly because I’ve never been in the cultural center building. Actually, I went in it one time when it was up for sale, a very short time before it sold. I had a big allergic reaction to being in the building, probably from mold or mildew. I barely saw it before I had to get out of there. It needed a lot of work at that point. It has been beautifully (and expensively) remodeled since then. I would love to rent it for a Pagoda reunion.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See Also

Author Events Calendar for Pagoda Book Release

Matheson History Museum talk with slides about the Pagoda, emphasizing Gainesville and feminist spirituality, Gainesville, FL, February 11, 2024

Rose Norman: Finding Lesbian Community in Alabama

St. Augustine Historical Society talk with slides about the Pagoda, emphasizing its origins in St. Augustine and connection to the women’s land movement, Markland House, St. Augustine, FL, February 1, 2024.

Head, Toni. “Changing the Hymns to Hers.” Heresies, 2.1 (Spring 1978): 16.

Murphy, Marilyn, “Pagoda, Temple of Love, 1994.” Lesbian Ethics, 95.2 (1995): 18-26.

Norman, Rose. “Alapine: Morgana’s Magical Mountain.” Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 146-49.

“The Pagoda, Florida, 1982, Conversation Between Morgana and Elethia.” In Joyce Cheney, ed. Lesbian Land. Minneapolis, MN: Word Weavers, 1985, pp. 111-115.

“The Pagoda…An Historic Lesbian Paradise.” St. Auggieland: The Strange, the Weird, the Auggie. The original article is no longer accessible but has been revised and moved here, https://stauggieland.wordpress.com/2011/11/08/a-lesbian-paradise. The blogger is identified as Alyssa, a Flagler College student from Kansas City.

Unger, Nancy C. Beyond Nature’s Housekeepers: American Women in Environmental History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. Pagoda is pp. 176-87, Alapine 182-85.

________. “From Jook Joints to Sisterspace: The Role of Nature in Lesbian Alternative Environments in the United States.” Chapter 6, in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire. Ed. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010, 173-98. One of the few published descriptions of the Pagoda in an academic book.