Moral Hazard: The South’s First, Out Lesbian Band

By Rose Norman

“Lock up the wimmen and chilluns! There is a Moral Hazard. It’s wending its insidious way into your consciousness with great doses of blasphemous comedy and garage band rock ‘n ‘roll,” wrote Mercédes DeLaGata in 1982 for The Gazette. That opening statement from a review of the lesbian rock band, Moral Hazard, captures the daring and delight that followed the band through that Reagan-Republican decade. Back when the Indigo Girls and Melissa Etheridge were still closeted, this wild and crazy, out lesbian band burst onto the Atlanta music scene with a blend of performance art, poetry, political commentary, and rock and roll. Moral Hazard was not like anything else going on in the 1980s though it sprang from a rich time of political theatre, improv, and garage bands.

Moral Hazard, an insurance term for people who are very high risk, was the brain child of Jan Gibson and KC Wildmoon, who began collaborating while performing in an all-women variety show called Other Harmonies. Jan was primarily a poet, known locally for powerful performances of her work. She often accompanied herself on guitar. KC had been in the all-women touring band, Anima Rising, which had split up in autumn 1979. [See “Consciousness Raising with Anima Rising,” Sinister Wisdom 104 (2017).] Jan and KC had been talking about doing something together ever since Other Harmonies. It was the night that Ronald Reagan was elected that they took action, deciding that they needed a band. Shortly after, with a couple other women, they wrote a song together, “Bomb Shelter,” as the band took shape.

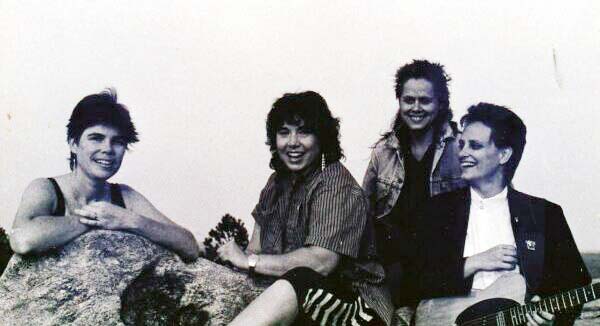

Enter Jaen Black, drummer, and JB Sapp, bass player. Along with Jan and KC, these four women made herstory as Moral Hazard throughout the 1980s and into the ’90s. Jaen had a background in political theatre with Red Dyke Theatre, but recalls, “I had never really played live music with anybody.”

JB Sapp was a professional sound engineer for the Atlanta CBS television affiliate. She had played many instruments, deciding during college to concentrate on bass guitar. Bass guitar made her more in demand for work with bands, and she soon found it was the right instrument for her. JB says that the four of them “just clicked. It was like puppies of the same litter.”

Jan Gibson knew the founders of 7 Stages Theatre in Atlanta’s Little Five Points, and she told them what they were doing. They arranged to do Moral Hazard’s first show, Flight 101, there, a midnight show following Brecht’s Mother Courage (!). KC remembers that they were amazed to see people lined up around the block for that midnight show, and credits Jan’s brilliance for making their first show “wildly successful.” Jaen recalls that “we didn’t know how people would take it, because it was some controversial shit—I mean leading up to Jan tearing pages out of the Bible!”

But their audiences loved them, perhaps because, as JB recalls, “we had so much more to say than just the music. We wanted to incorporate messages with it, activism, visual concepts.” And their audiences were ready for it. Years later, Jan would describe the highlight of their years together as a band and their audiences. She said, “To look out and see people beaming at us… It was just a real feeling of being embraced by your community, and of us embracing them.”

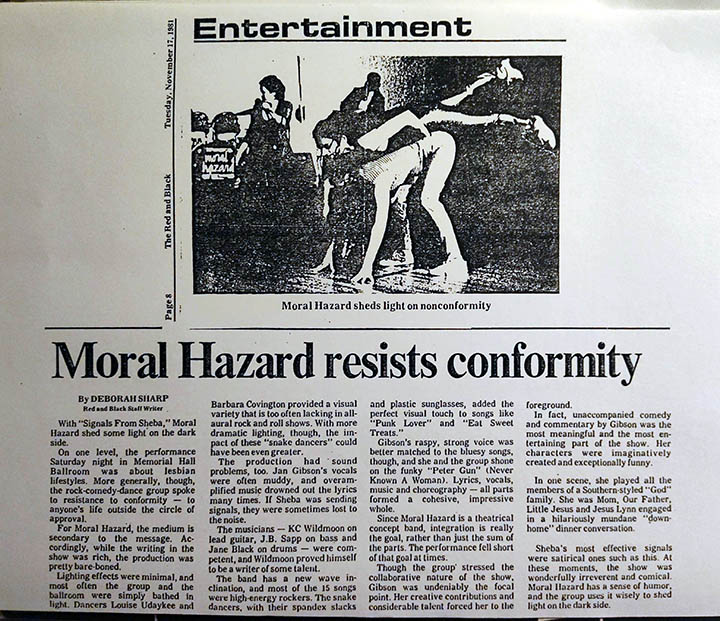

Their second show was Signals from Sheba, a spinoff from Jan’s one-woman show “Who the Hell Do You Think You Are? An Evening with The Queen of Sheba.” That was so successful a show that they toured it in Athens, Georgia; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Tallahassee, Florida. Jan was always the lead singer and songwriter, and JB recalls that the band collaborated on the music. She said, “Jan would come in with a powerful line or two, and we would sit and work out music for it.” Jaen and JB set the rhythm, KC did the guitar parts, and all contributed to the lyrics. They created their songs together.

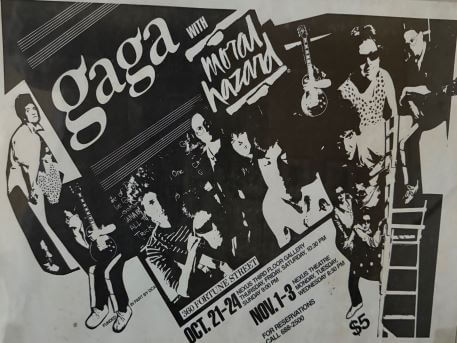

The core idea was to be a “theatrical concept band,” and they were flexible. They did their first all-music gig when the 7 Stages Theatre founders asked them to perform for a benefit. They played many more benefits, especially for the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA), and they never made much money for themselves. Often ticket sales would just cover rental of the performance space. JB recalls opening for the Washington Squares, saying “we got chances to play and we took them.”

For regular music gigs, they performed both Jan’s original music and some cover songs. They also performed at least once each at two big women’s music festivals in north Georgia: the Southern Women’s Music and Comedy Festival (1984-92) and Rhythm Fest (1990-95). When they applied to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, they were turned down. It seems strange now that MichFest didn’t want them because they were too “rock and roll.” The band did produce one album, Step Over This Line, with ten of their songs, available today on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Music. You can also listen here on a private Google drive. The first track is “Bomb Shelter,” their first song.

Jaen remembers “Take a Walk on the Dark Side” as their anthem: “It just sang to the heart of what it was like to be a homosexual and be in the closet.” Another song, “Eat Sweet Treats,” about food addiction, began with Jan sitting on the floor with a vibrator and a pile of candy wrappers.

Their most popular song was “Bisexual Girl,” a song that came out of a failed relationship. It begins with Jan’s monologue: “Hi, I’m Lisa. I’m bisexual in theory but not in practice. I am a part of the bisexual generation, and I always assumed I would have a brief affair with a woman when I met the right woman. It just hasn’t happened yet.” Then it slides musically into the challenging language Moral Hazard was known for:

“Have you done it?

How’d you do it”

Did you like it? Did you like it? Did you like it?”

For most of the thirteen years they were together (off and on), they usually rehearsed at JB’s house. Then, for a time, they rented a former Masonic Temple in Grant Park, in downtown Atlanta, where they both rehearsed and gave performances. Jan describes performing in the round there as “like a kind of hullabaloo.”

Each show started with Jan’s monologue about the audience. Then there would be songs and comedy bits, often as an introduction to a song. One bit in Flight 101 was about Jan’s “spiritual advisor,” Ricky Ricardo, a character from the I Love Lucy show. In another, the character Lillian, a kind of stick in the mud, led into the song “Punk Lover,” about the reptilian nature of some human activities. The song featured a refrain about our “snake brains.” That song gave a name to the “snake dancers,” two women who would weave in and out around the stage making slithering, snake-like movements. Moral Hazard was always four musicians and a changing pair of snake dancers.

These shows, which the band dubbed “no wave musical comedies,” a play on the “new wave” genre of punk music at the time, were very different from, well, pretty much everything in the Atlanta theatre and music scene as well as in the lesbian-feminist scenes. Led by Jan’s utter brilliance at capturing the realities of life, especially for women and lesbians in particular, Moral Hazard’s shows were fun, funny, thought-provoking, sensual, and at times, sexual. In the early 1980s, songs like “Punk Lover” and “Yellow Rose” thrilled audiences with deep and refreshing peeks into their own lesbian lives, which at the time, were often kept behind closed doors or at specific places where lesbians could be lesbians without fear of any judgment.

And here was Moral Hazard, celebrating all of that, out in the open for all to see. It was no surprise that the band was born in Atlanta’s Little 5 Points neighborhood, home to the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance, Charis Books and More, 7 Stages Theatre, the Sevananda natural foods store, and a host of other counter-cultural businesses and, of course, residents. It was the perfect place and the perfect time.

It was the later versions of “snake dancers” that eventually led the band to go their separate ways. It was not the original pair of dancers, Janet and Jo. It was another pair of professional dancers, which included Barbara, Jan’s girlfriend at the time. Barbara mostly created the show Gaga, a show that Jan ultimately hated. Jaen left before they did that show, and Joan replaced her on drums. “We all had different ideas of who we were individually, and it just fell apart,” KC remembers.

The four musicians who made Moral Hazard went in different directions after they broke up in 1993. Jan Gibson coparented a daughter and continued to write poetry and make art. KC Wildmoon stopped performing and continued her career in journalism. Jaen Black wrote two books, taught strength training, and won awards in Olympic weightlifting. JB Sapp became a sought-after freelance sound engineer for Super Bowls, World Series, eventually working full-time for the Disney Corporation.

Read more about the lives of these extraordinary musicians and their individual experiences of Moral Hazard in our interviews with Jan Gibson, KC Wildmoon, Jaen Black, and JB Sapp.

See also:

Moral Hazard, Step Over This Line, CD, ten songs, 41 minutes, available on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Music, or on this private Google drive.

Reviews

(Clippings from Jan Gibson’s collection)

Deborah Sharp, “Moral Hazard Resists Conformity,” The Red and Black, November 17, 1981, p. 8.

Maria Helena Dolan, “Sapphic Frenzy: Signals from Sheba,” Gazette Newspaper 2, no. 29 (July 16, 1981), section 8.

Maria Helena Dolan, “Slouching Towards Lesbos,” Et cetera 3, no 9, September 1987.

Mercédes DeLaGata, “Moral Hazard: Danger, Contents May Be Hazardous to Your Morals!” Gazette Newspaper, p. 8 (n.d., show title not given; says show ran three weekends at 7 Stages, so possibly Signals from Sheba, also reviewed by Maria Dolan).