Maria Cristina Moroles (Águila): Building Sacred Community on the Land

- Audio interview at Duke

- Águila Talks about Her Memoir

- Review of Águila: The Vision, Life, Death & Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains

Interview by Rose Norman via phone on Monday, October 27, 2014

Note: Some of the names of people have been changed to protect their privacy.

Family Background

I grew up in a West Dallas ghetto, in a large, traditional Mexican family. There was a lot of trouble living in the barrio, a lot of violence in that community, because it was a ghetto. It was common for there to be violence everywhere. My parents moved us to a better place, kind of on the edge of the barrio, but . . . things happened. Several things happened to me. I was raped at twelve and ended up leaving my home because I was pregnant. I was on my own from the age of thirteen.

The Baby That Resulted from Rape

I was forced to give the baby up for adoption to relatives in South Texas, where I had the baby. My aunt and uncle, who didn’t have children, took me in and took the baby. He was delivered in a bad situation, in a racist community. They were very cruel to me at the clinic. They did a forced delivery with forceps and injured the baby. [He’s been in a state institution since both his adoptive parents have died.]

After I had the baby, I came back [to my family’s home] and realized that I couldn’t live with my parents. Before that [the rape] happened to me, they had been very loving, empowering parents. But, in our culture, when a young woman is violated like that, it doesn’t matter what happened. Their way of being with me had completely changed. I had disgraced the family. I think my parents were overwhelmed with their economic situation; it just became very stressful. I realized that I’d gotten everything that I needed from them, and it was time for me to move on. I had always been very esteemed, as all my brothers and sisters were, and had been taught everything about independence and pride in our culture and who we were. It was such a dramatic change that my spirit knew this was not going to work. I left.

After that, I just lived on the street. Since I was so young, people kind of took me under their wing. I was very protected so lots of things didn’t happen. I felt protected and that was better for me. I found a new freedom in living that way.

Family Tragedy

About three years after I left, my 18-year-old brother, who was a gang member, was murdered. I came back to my family then, after years of estrangement, and I saw how vulnerable and broken they were by what had happened. I realized, not only that, but how broken they were by my absence, and my not giving them forgiveness for the mistakes they made and how they treated me. I realized that I needed to forgive my parents, move on, try to be a daughter again, and be of service to them, as a daughter. So, I returned, somewhat, to my family.

After that tragedy, my family moved away from Dallas, back to where we came from in South Texas. Even though I was returning to the family, I was again alone and pregnant in Dallas. I was pregnant with my daughter Jennifer when my brother was murdered.

Biographical Note

Maria Cristina Moroles (also known as SunHawk, now Águila) was born in 1953. She is president and executive director of the Arco Iris Earth Care Project , the nonprofit organization that works to fulfill the Arco Iris mission of preserving and protecting 400 acres of wilderness near Fayetteville, Arkansas. This land also serves as a survival camp for women and children of color.

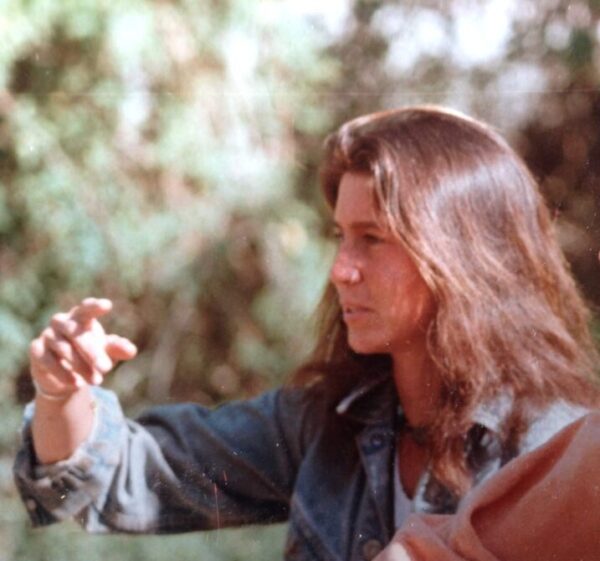

Águila Moroles is Native American, from the Coahuilateco Mexica nation. She has been a curandera, or healer, since the age of seventeen. She grew up in a traditional, Mexican-American family in Dallas, Texas, in a barrio plagued by violence.Águila came to Arkansas in the 1970s as a result of a vision that she was having in a recurring dream. She has lived on reclaimed native land known as Rancho Arco Iris (Rainbow Ranch), now Sanctuario Arco Iris, for forty years, much of that time without basic utilities.

Águila Moroles is a master massage therapist. She runs and directs a spiritual medicine lodge at Sanctuario Arco Iris. She has a daughter, Jennifer, and a son, Mario.

Married in Mexico

I went to Mexico and got married at the age of fifteen, as a way to have autonomy. I kept being picked up on the street for vagrancy as a minor, and put in juvenile detention. I learned a lot of stuff on the streets! I had an arrangement with my husband before I married him. We were both very young when we married [in 1968]. I was 15 and he was 16. I told him not to ever, ever tell me what to do, or try to control me. He agreed! He didn’t have a mother–his mother had died–and his father was a skid row alcoholic. He became my best friend [while I was on the street that first time], and we decided that [getting married] was the best way for us to keep from getting hauled into juvenile detention every time the police would catch us. So, we went to Mexico and got married.

It’s important to know where I was living when I had the vision.

The Dream of Home

All of that led to a vision that came to me. During the time when I was recovering from my brother’s murder and my own rape and all of that, I began to have a dream. It was a vision that came out of the blue. In this dream, I was on a mountaintop, standing alone, looking down into a valley. The valley was like a city, but the city was in… like a war. I could hear shooting and bombs exploding and people crying out. It was just a terrible scene that I was watching from a safe distance. I felt saddened by it, but I felt safe where I was.

This dream that I was standing on a mountaintop looking out at this chaotic scene of the city kept recurring. I began to think and dream of leaving the city and finding that mountain. That mountain turned out to be this mountain [where I live now, Rancho Arco Iris]. There’s a long story to it, too long to tell now, so I’ll jump ahead to when I was in Austin, Texas.

The Journey Homeward

I would leave Dallas when I felt troubled. I would hitchhike to Austin to clear my head. I was about eighteen, and I had already had my daughter [Jennifer, born 1971], I was living on the street again. On one of those journeys, I got sick. There was a young couple [David and Jennifer] who brought lunches to people on the street. They took me into their house. They told me about this land, this very land that I’m on now. They said, “There’s a community that lives way back in the mountains. We’re going to go live there. You don’t have to pay anything to live there. It’s an incredibly beautiful place.” [This place they described was then a hippie commune known as Sassafras.] They described the land. I was listening to their stories as they told me all about their trip. I think they had been there before and were going back.

They said, “If you ever want to go, we’ll be there.” They didn’t know the address, but they told me I could reach them at the natural foods co-op in Fayetteville [Arkansas]. They said they would periodically be going into town to work. I began the journey of saving money to move. I kept having that same dream, before they told me about that mountain and after. I realized that must be the mountain I was supposed to go to.

How We Began (1973-1976)

It was 1973 when I went to Arkansas. I didn’t move onto the land until 1976. After I went [to Fayetteville], it took me six months to run into them [Jennifer and David] at the co-op, but I waited. I’m very good at waiting. I got a job and waited. One day they showed up and told me how to get there [to Sassafras]. My husband was with me at the time, though we were about ready to break up at that point. He had gotten to be a heavy drinker, like his dad, and was just not in a good way. He was the sweetest person—still is—but he began to endanger my daughter and I.

One day he took off to get cigarettes with my two-year old daughter, and didn’t come back. I waited up all night, worrying. They finally showed up the next day. It turned out he had gotten drunk, and he had our two-year-old with him. That was it. I told him I could not allow him to endanger my child. That was where the buck stopped. As much as I loved him, and as much as I cared for him as family, we separated. We had been family to each other for almost nine years at that time. We got our divorce a year later. He went back to Dallas, and I stayed.

Falling in Love with the Land

Before that happened, David, Jennifer and I had gone to Sassafras community. When I saw the community that was living there, it reminded me too much of the chaos in Dallas that I had left. It was a hippie commune. They were doing drugs and alcohol, playing Indian and playing witches, trying on all kinds of different hats. I was not interested one iota in that. But the minute I drove up to that mountain, my heart opened. I knew I was home. I never saw anything more beautiful than that road. It was a beautiful dirt road, lined with huge oak trees, every kind of hardwood tree. I was in love! But when I met the community — ugh!

Rancho Arco Iris, where I live and have lived this whole time, is privately owned. The non-profit [Arco Iris] we started didn’t own any property. It’s all the same property where Sassafras was, but we actually live on another mountain, across the creek from the 400 acres where the commune was. This land is very rough; it comes down steeply to the creek. There are bluffs and only trails where you can actually get to the other side.

When it was a commune, Sassafras was a heterosexual community. Then the women rose up and threw out the men. So the hippie commune became a women’s community in, I think, 1976 or 1977, not long before I moved here. I wasn’t really a part of that community. It was Brae who carried me from Fayetteville out to the land and tried to save my life. Later she tried to strangle me. We were young wild women! But I have no hard feelings toward Brae.

There was no way I was going to live like that. They were still in the midst of the chaos. They just brought it out to the woods. I went back to Fayetteville. I went back to Fayetteville to cry about it, basically.

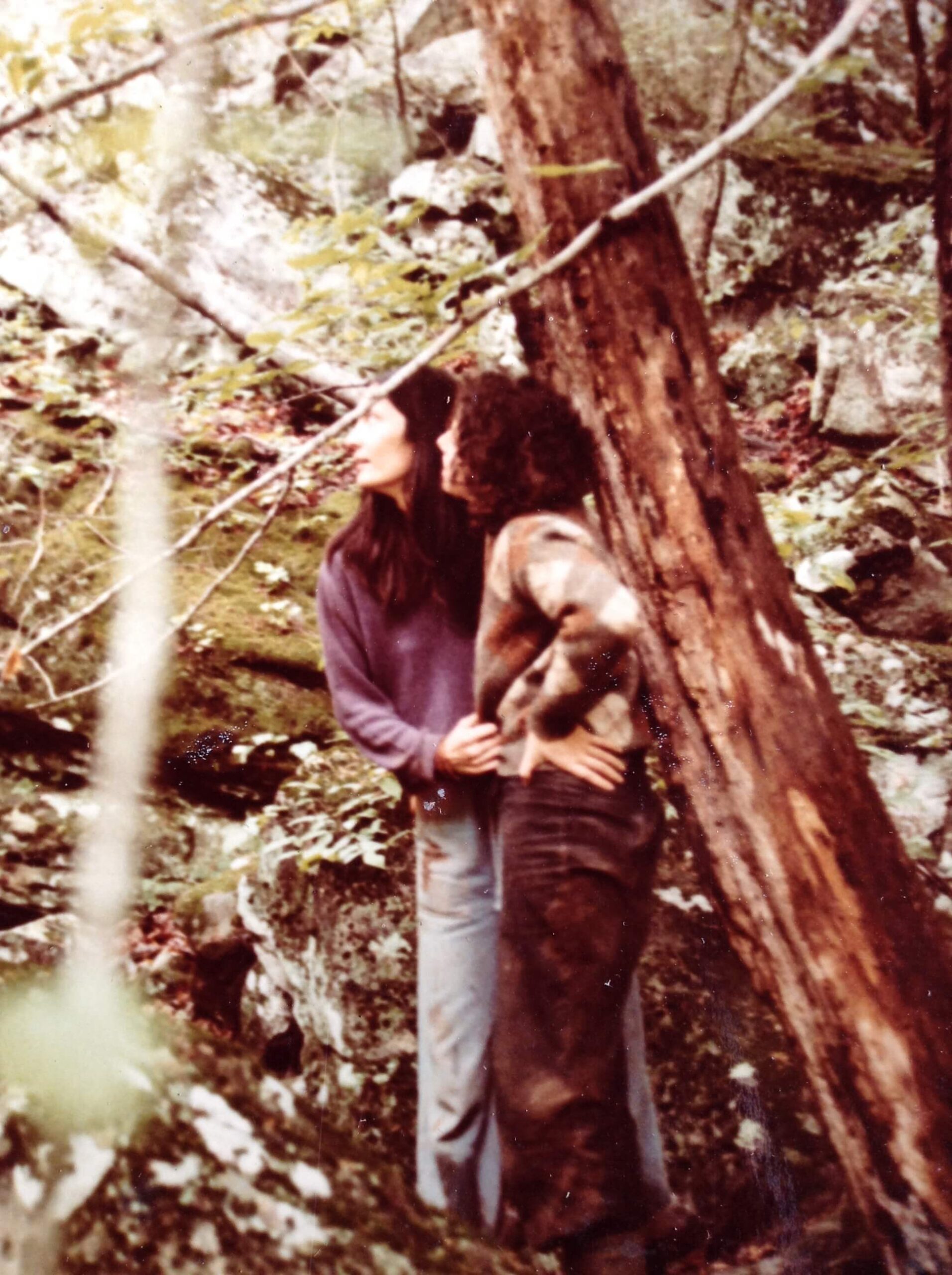

After my husband left, I got into a relationship with a woman, a dear friend, Shiner (Patti) Cardozo [she got her name from getting a black eye]. We had been friends for a couple of years. She told me the land had changed, that it was women’s land now. Again, my heart opened. It had been about two years; I thought I’d try it again. [It’s about 1975 now.] I went out, and she wasn’t there when I went. This woman, Leona Garcia, went with me.

We were greeted at the gate by very hostile lesbian women who asked who we were and what we wanted. I told them we were friends of Shiner Cardozo, and that she had invited us to come there. They said, “Well, she’s not here.” Once again, I saw that the land was not welcoming me, and I was very heartbroken again.

One woman who was there [at Sassafras] named Berry, a young nurse from Germany, came up to me and said, “I was here when you came the first time, and I saw you leave heartbroken. Now I see you again, and I believe you do belong here.” We talked, and I told her about my concerns and my sadness. She told me that there was land on the other side of the creek from Sassafras, land that belonged to Sassafras, and I could live there, away from this community.

I went away with that in my mind, that maybe that was what I should do. She told me how to get there, and I decided to go on and take that walk. The directions were like “go to this cabin, then walk down to the creek, and then cross the creek and walk up the other side of the mountain.” This is a long journey, and I had a four-year old with me. [It’s 1975 now] I did it anyway, and again I felt my heart opening. I again began to allow myself to believe that this was the place, the mountain in my dreams. There was nothing here, but there was peace.

I went back to Fayetteville and told my girlfriend, Shiner, what had happened. She was very apologetic about the hostility we faced when we went out there, of course. A lot of lesbians back in 1975 went through that separatist stage. They were coming out, taking back their power, and they felt they needed to isolate themselves and protect what they had. It was part of bringing the pendulum back into balance, but it kind of went to that real extreme of being separatist, and hostile, protective. I understood it, but I didn’t want that. I was tired of the racism and classism I’d lived with all my life.

Trucking for Ozark

At this time, I was a trucker for Ozark Women’s Trucking Collective, an all-lesbian trucking collective for Ozark Food Cooperative Warehouse. A woman named Ocean started the trucking collective. We drove semis all the way to Wisconsin to pick up cheese, and all the way to Texas and to New Orleans, and all in between there. Ozark Natural Foods still exists, but the warehouse is gone. Their building was built on a landfill that was leeching out toxins.

There was an epidemic of hepatitis that went through our Fayetteville community like wildfire.

Every woman in the trucking community got it.

There was an epidemic of hepatitis that went through our Fayetteville community like wildfire. Every woman in the trucking community got it. We were driving deliveries all over Texas, Louisiana, etc. I was one of the last people to get it. It went through the alternative community. It started in a restaurant where someone changed a diaper of a baby who had hepatitis. Hundreds of people got it.

At the time when I got sick, they had created different healing houses in the community, and the women had created a women’s house at Sassafras, a house where women were being cared for. There were women on the land at Sassafras who were caring for the women there who had come down with hepatitis.

I hadn’t gone back to the land since that last visit. Shiner was a member of the collective that owned the property. She would go out there, but I didn’t want to go. It was in a trust called, I think, Sassafras Women’s Collective.

I told Shiner, “Please don’t take me out there,” but she came home one day to find me passed out on the floor, burning with fever. I woke up at Sassafras. Shiner and Brae had taken me out there. A key part of the story was that my partner Shiner freaked out and left me. I looked like death! I was completely yellow and emaciated. That was the second time I’d had hepatitis. I had it when I was really young, from a dirty needle when I was a kid on the streets, so my liver was already damaged, and I had it in my blood. When I got it the second time, it really hit me hard. Shiner got scared and went off with another woman because she thought I was going to die.

At Sassafras there was a woman named Saturn who practiced Satanism. She had put a spell on a woman there, and I helped her get rid of the spell. While I was sick in bed at the main house at Sassafras, I heard a woman come in and bring a glass of water and put it by my bed. I picked it up to drink, and I tasted and smelled it and knew it was kerosene, and I spit it out and pushed the glass away, and a lamp fell over and the liquid started a fire. That’s when I knew it was unsafe to be there. Berry took me out of the main house and into a shed.

Death and a Vision

It was during that time that the vision for this place became crystal clear. When I was very, very ill, Berry, the one who had told me about the land on the other side, took care of me. I sent my daughter home to Texas because I was so sick; I thought I was going to die. Berry, and really all of the women at Sassafras, wanted me to go to the hospital. Because of the bad experience I had in a hospital, I had decided never to go to a hospital again. I decided I would just die on the land, on my mountain. I thought, maybe this is as far as I get, I get to the mountain.

I died, and I had a vision in my death, about this land and being on that mountain, here on this mountain. In the vision, I was told by a saintly-looking, young Indian woman with braids, a woman that I named Santa Maria, that I wasn’t going to die. I was just resting. I was going to start my life anew, and that I had a mission. The mission was that this land would be a sanctuary, a safe space, for women and children of color.

I died, and I had a vision in my death, about this land and being on that mountain, here on this mountain.

That’s where it began. After that, I wasn’t in pain any more, and I wanted to live. I felt good. I just wasn’t very strong for a while. This is the abbreviated version of the vision. It kept going for a few days. I was in a blissful state. Berry said that when I came back, a light glowed around my body.

The women thought I was dying, so they were drumming and chanting outside the shed. When Berry came out and told them I was dead, they kept doing that but more in a wailing kind of way. Then she went back in there and sat with me alone. That’s when, all of a sudden, she said that I took a deep breath, and a glow came to my body, a white light all around my body.

Shiner had left a beautiful white caftan as a burial robe for me. When I didn’t die, I asked for clothes so I could go outside, and she put that white caftan on me. There was snow on the ground. It was cold, but it was a clear, blue day, bright. The yard looked over toward the mountain where I am now. I did not feel cold at all. I felt very warm. I was barefooted, and felt that I wasn’t touching any cold. I sat on a mattress outside, and asked them to leave me alone. I felt alone, but don’t think I was.

My vision continued, and I saw three Indians. What you see when you look at this mountain at this time of year is a bluff line. What I saw was three Indians on horses, and one was waving to me with a staff, waving me to come. I looked into the sky, and there were all these buzzards flying around. Then a hawk came flying from the north right down into the center of them and scared them off. As it flew down, it flew right in front of the sun. That’s when I got my name Sun Hawk. I knew at that moment it was my name. I had a new life, and that was my new name. Even though it was just one hawk, it came and dispersed all those buzzards flying above me. Berry had already told me about that land, but when I saw those three Indians, I knew that was where I would be going.

After I got well enough, maybe two years later, I came over here, to Rainbow Land [now Santuario Arco Iris]. I had counseled with the seven co-owners, the collective, and told them about the vision. I asked for a counsel. I sat with the seven co-owners, and shared with them my vision. They had been there when I died and came back to life, and they were kind of freaked out about me.

Because of that vision, they decided they would turn over that land to me, this land that I live on. We put the land in mine and Leona’s names, even though Leona didn’t have that vision, and never spoke up for the land.

I like to refer to the land transfer as reclaiming our native lands. I don’t believe in owning our Mother. The vision was not that I would own it, but that I would be here to heal myself from my wounds, and provide a sanctuary for women and children of color. We became a survival camp for women and children of color.

It was very important that we began that way. As a woman of color and a Mexican Indian, I faced a lot of racism. All my teachers were white, and they were racists. Of all the teachers I had in grade school (I only went to the seventh grade), only my sixth-grade teacher was not racist. She was very loving and kind.

I knew that in order for us to regain who we are, we needed to isolate ourselves.

I knew that in order for us to regain who we are, we needed to isolate ourselves. We didn’t know who we were because of them bossing us and putting us down. We really didn’t! I realized all of that, and felt that we had to be alone here to work that all out. So we did. We needed our autonomy to remember our true and sacred nature as women, as natives of this land.

When I say “this land,” I’m speaking of North America, not just this land right here. My ancestors are natives of North America. My teacher told me that we emerged from the earth in Utah and migrated south by the vision of a medicine person that said we needed to follow the hummingbird south. When we saw the eagle perched on the cactus with a serpent in his mouth, we would have arrived. That is now Mexico City. My most recent ancestors, over the last two hundred years, are Coahuilatecos. Their territory is the state of Coahuila and all of southern Texas, up to San Antonio. There are a lot of different tribes of Mexican Indians in that whole area of southern Texas. They call themselves Mexica’s [pronounced muh-SHE-kuh] now, a general term for many different tribes.

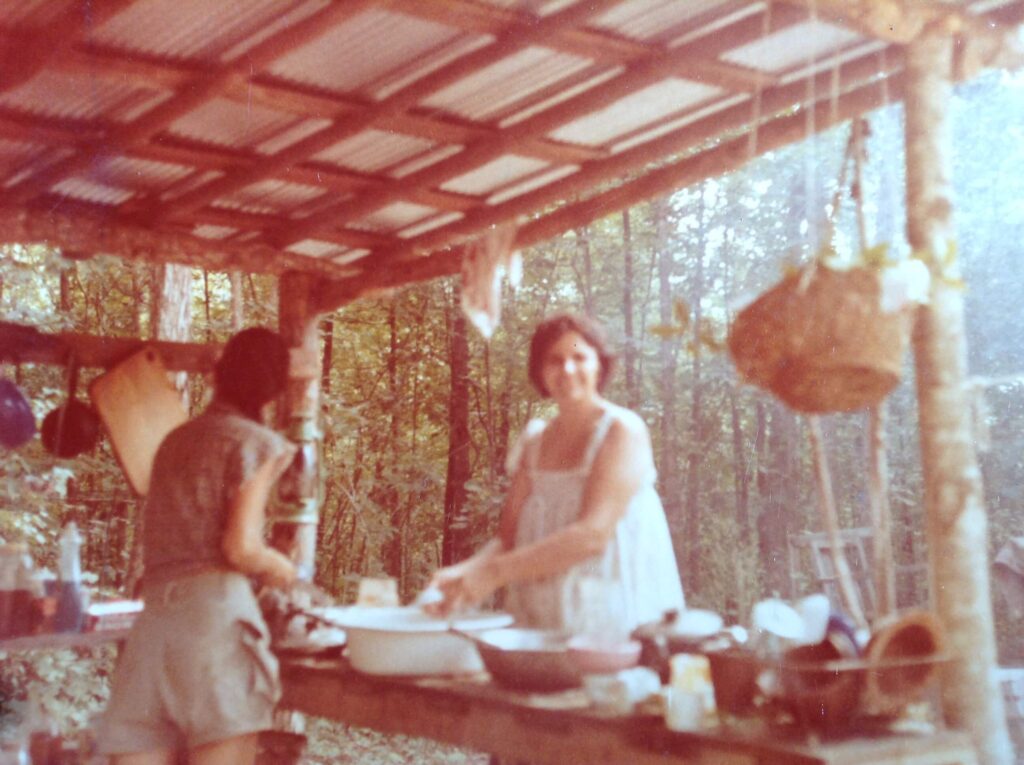

Women came; at first many women came. There was a big back to the land movement in the ‘70s. Gypsy women, women of color who heard about us through different articles, word of mouth, and festivals. We used to go to Michigan [the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival], back in the beginning [the first year was 1976]. There was a women of color tent, and I would always speak there.

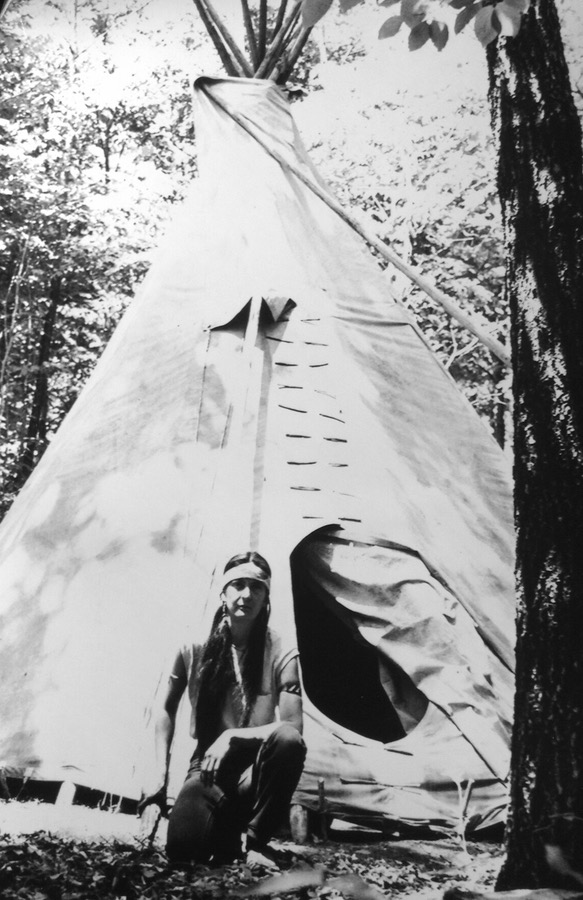

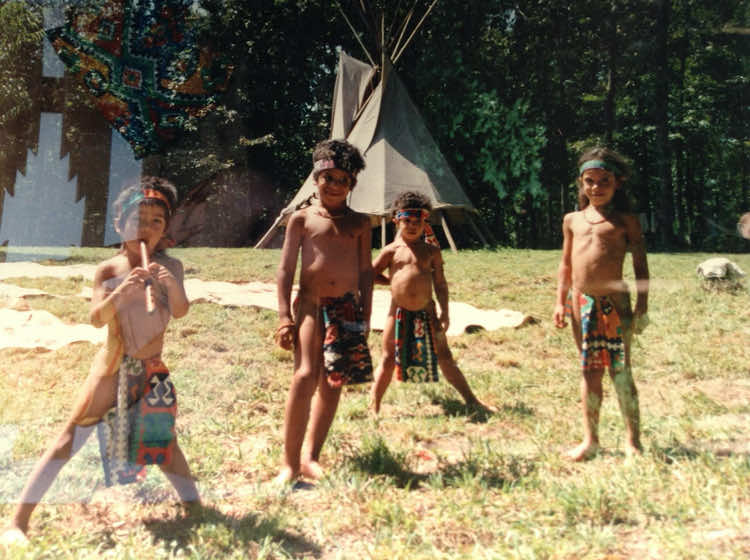

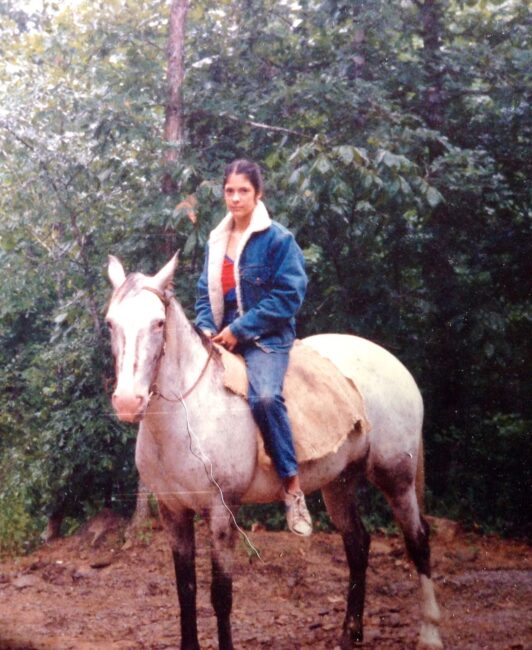

Women were coming, and they were all wounded. We were all so wounded. It was crazy. We didn’t have any money. I was recovering from hepatitis. I went into liver failure when I died. I had a miraculous recovery, coming back to life, but it took my liver two years to recover, two years of not being able to work, and seven years total to really rebuild it. We lived on food stamps, out of tents and teepees, just lived here on the land without running water. It took us all the way back to the beginning. We had horses for hauling our stuff up the hill. We went to the store once a month, when our food stamps came in. The rest of the time we were here, learning how to grow a garden.

That’s how we began.

What We Became

We had women come and go. At first it was a lot. It got less and less as those women who had that dream of escaping the madness of the city life and living on land came and tried it, and found that it’s not easy to live in a wilderness area. They were urban women escaping their traumas and tragedies. I began to take care of children because I had a little girl, and there were all these women coming here who needed to get themselves well, and they would come and go, and often leave their children with me. And I loved it because it gave my little girl someone to play with.

I actually preferred the children to anybody else, because of their innocence. But they were also very damaged from living with their mothers, coming from broken homes. Many were latchkey kids who were often left alone. I’d find out about it and tell the mothers to just leave them here awhile and go figure it out! The women would go home to their parents, or go home to their partner, or whatever. It wasn’t easy living out here in tents, because they were used to living in houses, so they would leave their children.

When Shiner Returned

The beginning of the second year I was here, living alone with my daughter Jennifer, my partner Shiner showed up. She came back dragging her tail behind her. She told me she was sorry, that she had gotten scared that I was dying and had run away from it. She couldn’t face the death. So, she came back, and she said she loved me, and we’d already been good friends for two years before becoming lovers, so she came back and lived with me. We lived here for five years together. We were very different, though. We were from opposite ends of the economic scale. She was from an upper-class, Jewish family from Minnesota.

I told her the vision, and she was all for it, and we began to work on it, as stewards. I didn’t believe the land was supposed to be mine, but to share as a sanctuary. We needed to get it out of Sassafras’ name, so we had put it in my name, mine and Leona Garcia. Leona left, but Shiner stayed.

When Shiner came back, I was here alone with my daughter, Jennifer. Shiner told me that her grandmother was very ill and dying, and that her grandmother had played a very important role in her life. We ended up going to visit her grandmother in Minnesota, and we found that she wasn’t dying. She was a survivor of the Holocaust, and she thought she was in an internment camp [she was in a nursing home]. I suggested to Shiner that we bring her here, from that nursing home. Her parents objected that we didn’t have any place to take care of her, or any place for her to live. They had her in a very nice nursing home.

First, we went to Minnesota, took her out of the nursing home, and took care of her in an apartment for nine months. Then they let us bring her back in a travel trailer. She lived here on the land in that while I built the house that I live in now. The fact that she came to live with us helped, financially, to build this place. They helped us with the initial costs of building the house, $5,000 that got us started. It was a full-time job for Shiner, taking care of her grandmother. She was bed-bound and all that. It was a lot of work for us, but it did enable us to upgrade, since we got $2,000 a month for that caregiving. My family was still living in a teepee. Others were living in tents.

Cupid Strikes

During that fifth year, I met Luisa at Michigan. I wasn’t looking for anyone at all, but here was this woman who was from a New York City ghetto, from a large Cuban family. She came here and was here about six months before we ended up falling in love. This was unexpected—I was in a relationship with Shiner.

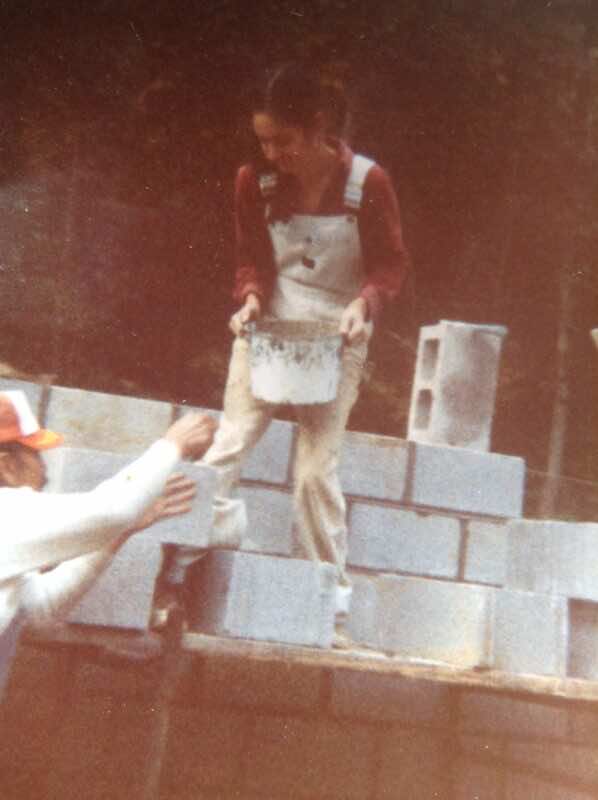

At Michigan, I had asked Luisa to come here and help build the house I live in now, in exchange for living on the land. One day Shiner was in town with her grandmother and the kids. When somebody went to town, they stayed a couple of days, doing all the chores, the laundry, the groceries, etc. She’d stay with friends in Fayetteville while they got all that done. Luisa and I had never been alone together on the land. We were working on the roof, with no shirts on, putting on the decking.

All of a sudden, I swear to God, it was like Cupid hit me with an arrow. I looked at this woman, and that was it. She was the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen in the world. I thought, “Oh my god, it’s her!” The Creator sent her to me, and I hadn’t even noticed her in months! We’d been working side by side. I’m a very driven person and very loyal. But it happened. I looked at her, and she looked at me, and she knew what had happened, because it hit her, too. We were working maybe ten feet away from each other. She said she knew when she went down to the cabin that night that something major had happened that had to do with us. So that’s how Luisa and I began, five years after I first moved here.

Luisa knew all about our mission to be a sanctuary and was all on board. It all began to change when we decided to have a baby, because we had a baby boy. Now, we had been taking care of little boys [whose mothers brought them to the land]; we’d never been separatist in that way. I never was a separatist even with women coming here. Women would come who were white. It was known that this was women of color land, but I hired this German woman, Eva, who was a carpenter and helped me build the house. We had white friends who came here, they were not excluded, but this was known as women of color land.

Mario

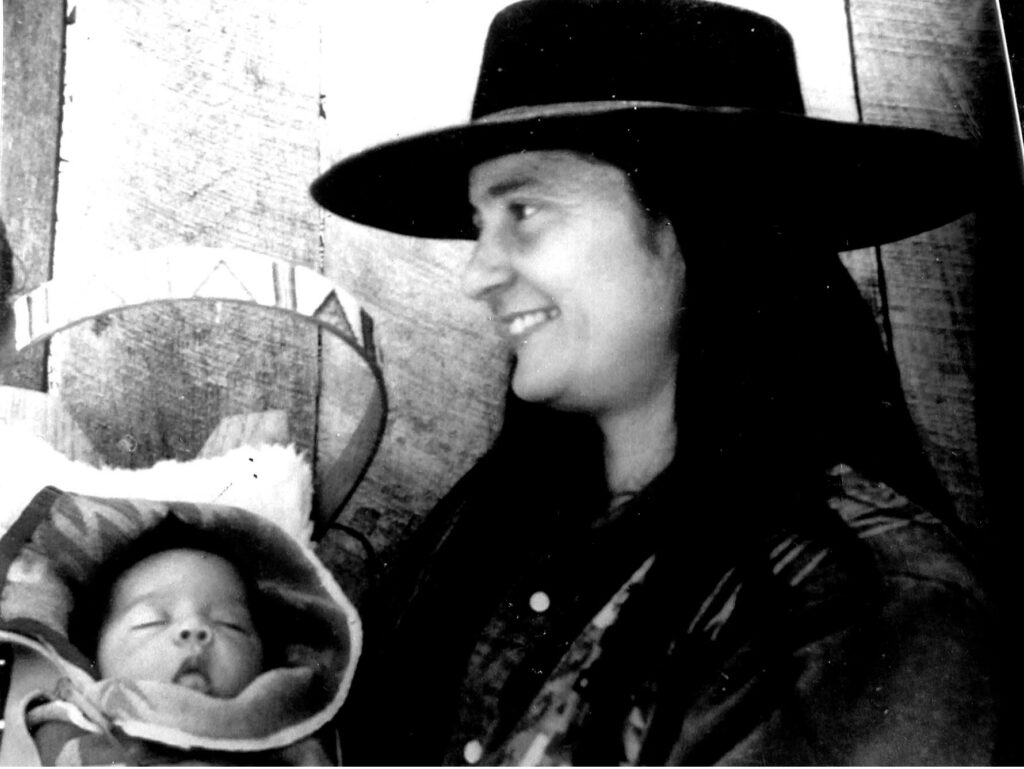

I inseminated Mario here, and Luisa birthed him. He’s related to both of us; his father is my cousin. I delivered him in the very room I’m talking to you from right now. I delivered him because, during the last month, the midwife would not come because her husband forbade her because we were pagans. She’d already told us there was potential for a difficult birth, because of Luisa’s narrow hips. And it was difficult.

Women of all colors were here for his birth: an Asian woman, African American, two white women, several native women. It was winter, February 1, and it was cold. There was no running water then, but we had a plan.

It took all of us to bring them through it alive. It was sheer women power

that brought them through that near-death experience.

It was an incredible birth. It took all of us to bring them through it alive. It was sheer women power that brought them through that near-death experience. She was not dilating, and Mario was stuck. I had the sense that he was going to die if we didn’t do something right then. I called everyone in, and we all pushed. It was like the whole room moved, and he was born. He had a knot the size of a golf ball where he had been stuck, and Luisa tore and was very weak from 46 hours of labor. She started getting a fever, and he had labored breathing, so we decided to take them to the hospital.

Still it was very, very hard, very traumatic. I didn’t realize for years the impact it had on us. Mario almost died, and Luisa almost died. We had to go to the hospital after he was born. He was flown to Springfield and Luisa was treated in a very racist hospital in Harrison, Arkansas. I was not with her because I went with Mario to Springfield, Missouri.

My Asian friend was with Luisa [in the Harrison hospital]. The hospital treated Luisa horribly, told her she was rotten, she stunk. Mario was taken away from her when they were in two hospitals. She really clung to him after that, and blocked me out.

Things began to change when we had Mario. We couldn’t go to Michigan any more, and we weren’t about to be separated from him. After she almost died on me having Mario, there was no way we were going to Michigan and be separated from our child.

Mario is the most loving, gentle soul. He drew our community—this Bible Belt Christian community—together around us. They were all so drawn to him. All the white people who would never speak to us before, somehow just fell in love with him. “He’s a dandy!” they would say. This little fat Indian baby in a cradle board. Everybody wanted to hold him and touch him and feed him.

What I say to everyone is that we prayed him [Mario] down. When I say we prayed hard for him, we weren’t praying for a boy, we were praying for a baby. He was inseminated on the first try, and we did it in ceremony. That night, the owls all hooted when he entered the earth. He’s a musician. He and my niece sang “Let It Be” for my mom, as the opening song for our Thanksgiving dinner this year. He’s our firekeeper at the ceremonies for the men. He runs men’s lodges for men, and I do women’s lodges.

Our lives changed. Once we stopped going to Michigan, the flow of women to the land began to lessen. That was where we let women know we existed. We became more inclusive than we had been before, though we’d never been separatist.

Sometime, maybe 1984, we incorporated as a non-profit, hoping to get more [financial] help. We had decided from the start that we would not include the land in the non-profit. At first, we had programming for women and children of color, then it began to include rural, disadvantaged children, because local children who needed a place to be would show up. There was a white woman who showed up with three half white, half Black children, and left them here and disappeared for two weeks.

We didn’t have a phone; the closest pay phone was nine miles away. We had no electricity and it was three miles to the mailbox. The non-profit didn’t actually help us that much, except for when we went to the co-op. They would give us food and stuff for our events, camps for the kids and for women. That’s how things began to change.

Now we had a child of color of our own, a boy, and we wanted him to have other children around, whatever he needed. Jennifer, my daughter, was 17 when Mario was born [he was born February 1, 1988].

A Departure

An article Luisa wrote for Maize [“On the Precipice of Beauty,” published winter 1990] reminded me of how things were changing then. Luisa began to get very, very disheartened by the way things were turning out. Our dream didn’t seem to be coming true the way she had hoped. Women would leave, they wouldn’t stay, and she became more and more disheartened. I felt it, too.

People were in awe of our love. We were kind of the cornerstone for lesbian love. We wrote each other love poems. We loved each other so much, went through so much in those 28 years.

Luisa gave it a good go. We were married 28 years. Luisa left January 1, 2011. She did her best, but something was missing, and she needed to go find it. She wanted me to go with her for years, go back to town, and then retire here. She began to see this place differently. She’d given so much; she felt like the land should give back to her. She saw the land more as a resource, and talked about things I didn’t want to do, like selling some of the land. We struggled more and more.

Transition to Arco Iris

Arco Iris means rainbow in Spanish. Rainbow to my people is the rainbow goddess, the goddess of healing. She is all the colors, meaning all the colors of all the peoples. This land has always been about all colors living together. We, as Indigenous women, are the stewards of the earth. As Indigenous daughters, we should maintain the stewardship of the land.

It didn’t mean that many people always wanted to go there, or that it’s exclusive of other people, only that we must, must, always remember that the people of color are the most disenfranchised, that we must maintain a space [for them]. We must remember that this was put in our trust, that we maintain that leadership. There’s a misunderstanding that this is a space for women of color only. I hope that the leadership will continue to be Indigenous women of color. That’s why we are called Arco Iris. That’s a very important piece that is misunderstood often.

Because I do talk about experiences of racism that still go on, and that I lived through it, people will take that too personally. I say if the shoe fits wear it; if it doesn’t, throw it away. There have been misunderstandings about that.

Last night a woman arrived. I’ve known her since she was eleven. Her partner just committed suicide. She’s a white woman with some Indian blood, Cherokee. A lot of the people around here have Cherokee blood because the Trail of Tears came through here. But for all intents and purposes she’s basically a white girl. I embrace her and love her as anyone who comes to me as my sister or brother.

This land is a sanctuary to all. However, I must maintain this space

for those displaced and marginalized Indigenous people.

I do not turn away men or white people. I don’t turn anyone away, if they come and ask me for help. That is my vow as a healer, to help as best as I can with what I know. This land is a sanctuary to all. However, I must maintain this space for those displaced and marginalized Indigenous people.

About the Land

There was no road, no water, no cleared land. We didn’t have a truck for a year, until I traded my motorcycle for a little black Ford pickup that lasted about a year. One day, we lost our brakes coming down Cave Mountain, and I totaled it. There was a washed out, three-mile long, hundred-year-old logging road that hadn’t been used in almost forty years, I think. It had trees growing in it. We walked in.

There was nothing between us and the national park. There were two one-room unfinished cabins on the land that we worked on so that women could stay in them. One has gone back to the earth. The other one is now Jennifer’s cabin and has been completely reconstructed from bottom to top, and added onto.

We had been living here, building our garden, building our home. There was no phone service for three miles. We put in everything that’s here now: irrigation, a garden, a pond. We finally got an antenna phone when Mario was three or four, 22 years ago.

[The following is about improvements to the land since the articles published in Maize, when there was no electricity, no running water, and a 500-foot well that didn’t work.]

Our first source of water was carrying one-gallon jugs an eighth of a mile from the spring. The second source of water was putting in a pond in 1980. That provided us swimming, fishing, irrigation for the garden and water for the animals and wildlife.

Then we did a hand-dug well. The men, well-diggers, put an explosive in the ground without my knowledge. That ended that way of having a well. I didn’t want them setting off bombs here of any sort. Then we had well drillers drill down into the earth, which seemed gentler. They didn’t hit water for 500 feet, and we didn’t have any way to get it up. The only pumps at that time were only guaranteed on regular power, not generator power. I’m sure they did that commercially, but not for homeowners. We still have a 500-foot well that doesn’t work.

We developed a water spring as our main source of water, so we have spring water, still our main source of water. I haven’t had the money to invest in a different kind of water pump for our well that would use our solar power; that might work. But I haven’t investigated that in decades, since we rely on our spring. Until about ten years ago, the spring ran three seasons. We have two 1,000-gallon tanks, and a 300-gallon settling tank to hold the spring water. We never went back to that other well.

Luisa and I hand dug a cistern next to our house and built a cement tank in the ground. It holds 900 gallons of rainwater, or whatever you want to put in it and has a hand pump. We don’t use that for drinking water because we mostly fill it with rainwater. We had a drought a few years ago that was so extreme that ponds went dry. Our irrigation pond, a three-quarter of an acre pond, was one of the ones that didn’t, but it went down from about 8.5 feet in the deepest part to about 3 feet. We water our animals from the pond. This year we had three seasons of rain again, enough to fill those tanks with enough water to last us through the three or four months without rain. When the tanks run out, we have to haul water from a spring in Boxley, five miles away. This is the first year that we’ve had three seasons of our spring running in about five years.

Procuring the Land

In 2000, we decided to ask for the land that had been the Sassafras community. The land had been abandoned for ten years. Poachers were vandalizing that property next to us and shooting, hanging out there. It’s right across from us, so we asked for that property. It’s a long story, but I’ll just say we asked the owner for that property. I actually became one of the owners when my ex-partner Shiner* was the last one of the collective owners to be asked to sign off of that land. When they asked her to do that, she put me as her power of attorney, so legally it was owned by me and the original purchaser of the property. We decided to put it into a non-profit.

* Shiner and I had reconciled. She was planning to move back to the land from San Francisco when she died [May 16, 2001]. I was probably the last person she talked to, on the phone, before she died. I used to go out there and stay with her during allergy season (September-October). She had lung cancer. I noticed that the garage downstairs belonged to a landlord who owned a lot of houses and kept all his chemicals and paints there. It had two vents that were right by Shiner’s window. I felt like that was what made her sick. She had been very healthy.

I had no idea what I was doing at that time, I just followed the lead of the guidance I had asked for. It’s a great responsibility, a great burden to take care of that 400 acres. That is the only land that is owned by the non-profit. It is wilderness land. Homesteaders used to buy land in 620 acre plots. The original owners had that much land. They sold off a little of it, and, when the women took over, the collective gave one heterosexual couple 40 acres because they were living there with their children.

Summary

This summary was written by rose Norman and confirmed by Águila.

Rancho Arco Iris is the original land that Águila reclaimed for Indigenous women of color, originally 120 acres. Another 20-30 acres where the spring is was purchased, funded by Lesbian Natural Resources (LNR). This is where Águila still lives. When Leona left, her name was removed and Luisa’s name was added to that land.

Arco Iris, the nonprofit, owns the 400 acres across the creek. [Legally, it’s 390 because Diana Rivers and Path Walker still own a life interest in 10 acres. On their death, it goes to Águila and Luisa. There is a one-room cabin on that 10 acres.]

Altogether, the land that Águila stewards is about 530 acres.

Our Mission Today

Our mission today is still for all this land to be a sanctuary, not only for people, primarily women and children of color, but for this land itself. It’s an incredible forest with elk and bear and wild turkey and wolves–we even have panthers here. We have deep woods, deer and all the small animals, and incredible wild medicinal plants that are rare: ginseng, goldenseal, Echinacea, black cohosh, and blue cohosh. So many basic medicines grow here.

I went to the University of Arkansas law school a couple of years ago for help in getting the land protected. They started trying to help us, but, at that time, this land was in dispute with Luisa, and there were other issues. They said they couldn’t work on it any more until all that was settled. We lost our Internal Revenue Service (IRS) non-profit status because the person who took over that paperwork after Luisa left didn’t send in the form for two years. In the third year, we got a final notice, and she sent it in, but we lost our non-profit status for a while.

We have been reinstated as a 501c3 [non-profit], since the problem was due to an error. The land dispute has been settled (not paid off, but it’s settled). Since the land is now solely in my name, I personally owe Luisa $15,000. Then the land will be free again, and I can put it in a trust.

[When Luisa left in 2011, she sued Maria Cristina Moroles for a share of the land, now called Rancho Arco Iris. That lawsuit was settled through mediation, and Moroles is fundraising to pay off the settlement in installments. In 2011, Luisa transitioned to a male identity. The settlement was $27,500, and Moroles raised enough to pay the lawyer and $12,500 toward the settlement amount. Another $15,000 was still owed, and has been paid off as of 2024.]

Without protection for the land, those who come here are not protected.

I do hope to return to getting legal help for putting this land into a trust as a sanctuary for all those things I mentioned. We are one of the most pristine, unlogged. Some areas were never logged, some areas were logged in the last hundred years, some areas were selectively logged. Having the land protected is a major, top-of-the-list item. Without protection for the land, those who come here are not protected. We want to create a stewardship agreement to hold the land in perpetuity. I’ve written a draft that says that Indigenous women will live on the land and work on it. The draft gives guidelines for how to care for these lands for future generations.

It’s a very complex thing that I’ve taken very seriously as a sacred responsibility. Our mission now is to heal our community, our local community, our Ozark community, and our Indigenous community, and to bring all the colors into sacred union again.

I know that’s quite ambitious, but these ancestors have been quite insistent with me. The ancestors called me back, and they knew exactly who they were dealing with, what kind of person would persevere, despite all the obstacles I have faced. I have always maintained that we as the Indigenous daughters of the earth would maintain that leadership role, and do whatever we have to do in this white world that we live in, this society that we live in.

We as women, we are the daughters. We know more about the sacredness of life.

It’s very hard for me as an uneducated woman. I only went through the seventh grade. I got my GED by going to night school when I was very young, but I don’t have the same resources in the academic area that are required. But I do have the perseverance and the vision. I pray that if this is what these ancestors called me back to do, that I will be able to do that. When I travel, I see the importance in it.

We as women, we are the daughters. We know more about the sacredness of life. I’ve given birth. I know the pain and the love that it requires to have a child. We are more like Mother Earth, because she births us every day. In the matriarchal Indigenous way, it is the women who are responsible for the care and the stewardship of the land. That’s important right now, when we see the destruction that has come from making the earth a commodity to be bought and sold and raped and pillaged for her resources. I think that men will never have an understanding of the sacredness of the earth, our mother, as great as women will.

Medicine Name

My medicine name is now Águila. After I died that first time, I was given the medicine name SunHawk, through a vision. But about three years ago, this changed. I earned my eagle feathers, so now my medicine name is Águila, which means eagle. So many people still know me as SunHawk. For over thirty-five years, I let them call me . . . whatever.

I have a teacher, an Aztec woman.She gave me an eagle feather and a headdress, and she told me to put all my eagle feathers in the headdress and wear it, that it would give me strength. In our tradition, eagle feathers are like badges of honor, and I’ve received many over the years. Eagle is spirit, and it brings a message from spirit to the earth.

Spanish was my first language, my language until first grade. My English sentences are often reversed, because when you write or speak in Spanish, you begin sentences almost the opposite of how you would in English.

Looking to the Future

The vision now is to get some young blood here! My son is here now. He was in the Coast Guard for three years. He came back, and now it’s just the two of us living here. My daughter lives about 25 miles away. She recently told me that she and her partner are thinking of moving back here. I also have an apprentice who is thinking of moving here, a young woman.

I am a lodge keeper. This is a spiritual land; we do ceremonies here year-round. People come here for spiritual healing. I run a spiritual medicine lodge (white people call it a sweat lodge), and my apprentice is going to start pouring water for me this Saturday, in my place. You’ve heard of Día de Muertos, Day of the Dead? On November 1, we are having a ceremony, and we’ll have a lodge, and she’ll begin pouring then. I still do it, and probably will continue to do it, but it requires strength, and you’re sitting on the ground, so it’s time for her to start. I’m a master massage therapist, so I use my hands quite a bit. I need to be gentler with my body as I go into my 60s.

Timeline

1953 Maria Cristina Moroles (MCM) is born

c. 1965 MCM raped, age 12, becomes pregnant; gives up baby for adoption

c. 1966 MCM leaves home age 13, and lives on the streets of Dallas

1968 MCM marries, age 15 (marries another street kid, a boy aged 16)

1971 MCM’s daughter Jennifer Jo born

1973 MCM moves to Fayetteville, Arkansas, with husband; divorces husband, who returns to Dallas.

1976 Sassafras cedes neighboring land (120 acres) to women of color, who name it Arco Iris.

1976 MCM comes to the land with her daughter Jennifer and friend Leona Garcia (date based on 1986 Maize article that says, “Jennifer has lived on the land since she was six,” implying that article was written in 1985). The deed is in the names of MCM and Leona, until Leona left. Luisa’s name was put on when Leona’s name was taken off.

1979 Arco Iris land deeded to Maria and Leona; later, 40 acres is deeded to Luisa as part of a legal settlement

c. 1982 Luisa comes to the land; MCM has been there 5 years

1984 or 1985 gets nonprofit status

Feb 1, 1988, MCM and Luisa’s son Mario born on the land; Luisa gives birth, MCM delivers

2000 MCM asks the collective who still own Sassafras to give Arco Iris the Sassafras land, 400 acres. They sign it over in the name of the nonprofit, Arco Iris Earth Care Project. Diana Rivers retains a life estate in some acreage.

2011 Luisa leaves the land after 28 years

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University.

See also:

“Arco Iris, Rainbow Land: The Vision of Maria Christina Moroles,” Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 46-52. Rose Norman condensed these interview notes (over 9000 words) into a narrative of about 3000 words. Águila edited and added to this for the final draft submitted to Sinister Wisdom February 14, 2015.

Águila Talks about Her Memoir, interview on April 2, 2024 by Rose Norman

Rose Norman, review of Águila: The Vision, Life, Death & Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains (University of Arkansas Press, 2024).