Falcon River: An Amazing Appalachian

This is a companion interview to Jade River’s interview, and on the origins of the guardian priestess path.

Written by Salkana Schindler from her interviews with Falcon River on July 29, 2022, and on September 14, 2022

Falcon River: I was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1952. I grew up in the Appalachian Mountains of southwestern West Virginia. I was born in Ohio because a lot of the folks would make sure to go up to Ohio, to either Cincinnati or Columbus, to the hospitals to have their babies because there was no formal medical care where we grew up. We called the roads that led out of southwestern West Virginia into Ohio “the Hillbilly Highway.” People usually cross at Point Pleasant or other points of crossing, you know, over the Ohio River. Women would go over the river to have their babies, and then, come back. It was safer that way.

My mother was older. She was 42 when she had me, and I was her only child. My dad had many other children by many other women. My face is the face of southwestern West Virginia. I grew up in Greenbrier County, in a little town called Alderson.

[Alderson, West Virginia, spans both sides of the Greenbrier River. The population was 922 in the 1950 Census, around the time when Falcon River was born. In the 2020 Census, the population was only 975.]An interesting thing about Alderson is that it’s where they have the Women’s Federal Reformatory. A lot of very famous women have gone to prison just outside of Alderson, like Tokyo Rose, Axis Sally, Martha Stewart, and Squeaky Fromme.

FR: I went to primary school and I did not graduate high school. It used to be that every little town had their own school system from grade school up through high school. When I was in tenth grade, the powers that be decided to build a high school at each end of the county to divide us into East and West Greenbriar. I couldn’t make that transition, and I didn’t finish high school. I did eventually get my General Equivalency, my GED. I’d taken the test, and I did eventually do some college. But it didn’t really interest me.

[In the USA, the General Educational Development Test, or GED, once passed, confers the credentials of a high school equivalency.]FR: Pretty much. Yes.

Biographical Note

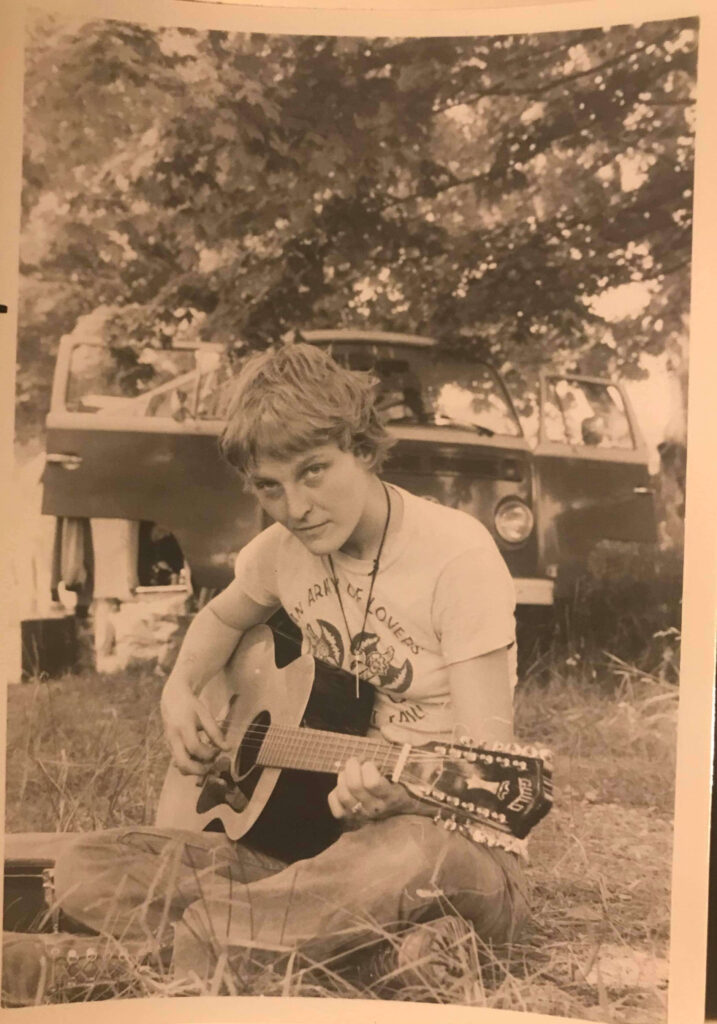

Falcon River, born in Ohio in 1952, grew up in the Appalachian Mountains of southern West Virginia, climbing the trees and crawling into every cave she could find. She describes her family as a “proud line of moonshiners and thieves.” As a child, she was trained by her family elders in woodcraft, as well as in traditional folk magic and medicine.Being “wild” herself, Falcon River left home in 1968, coming out as a butch lesbian soon after leaving. She lived in California and in Virginia. She won the title of drag king, “Mr. Roanoke,” in 1973 and 1974.

In 1975, in Louisville, Kentucky, Falcon found Jade River, an old flame. They managed a private club and bar for women called “Mother’s Brew,” providing within it a feminist library, art gallery, and battered women’s safe space.

Falcon River was introduced to Goddess-based religion at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival.

FR: My first, long-term, female partner was Jade River. We met when we were both at Girl Scout Camp. She was a Counselor in Training (CIT) and I was a camper the first year that we met at Camp Ann Bailey in Caldwell, West Virginia. The second year, she was a counselor, and I was a CIT. It was that sweet, young, first passionate… we didn’t know what we felt. I mean, we knew what we felt, but we didn’t know.

FR: Yes, not sexual. But just amazing and strong. We immediately had a telepathic connection. We knew at any given time where each other was on the grounds of the camp. We practiced and played with that a lot. Even at that young age, Jade had already begun to explore reading about the Craft [Wicca] and about books on occult, things that I was not the least bit familiar with at that time. I was 14 years old. We stayed in touch loosely over the years. Come to find out, later, many letters that I had sent to her were intercepted and hidden by her mother. Jade thought that I had abandoned communication when that was not the case.

Cut forward [from the mid-1960s] to 1975. Jade was living in Louisville, Kentucky, and she had gotten married to a millionaire. She had a little boy. I was coming to Louisville to help a friend of mine who organized folk festivals. There was a folk festival on the grounds of the University of Louisville campus. I was there with my friend, Minnow, to help out with this folk festival.

I wrote to let Jade know that I was going to be there. That was the first time we’d seen each other since we’d been to camp together. As soon as we met up and saw each other, that connection was right there. The difference being that in the time span between Girl Scouts and 1975, I had come out. We very quickly realized that we wanted to be together.

She left her husband. I moved to Louisville, and we set up housekeeping together. We were directed by a mutual friend to a feminist lawyer, a woman lawyer. We were looking for someone to help her with her divorce because back then, children were simply removed from the homes of lesbians and gay men, and the children were made into wards of the court. Fortunately, our lawyer, Emmie, was extremely skilled, and she helped us. She managed to work through the custody arrangements, and joint custody arrangements happened.

Lesbian Feminist Union

FR: In the process of that custody battle, and in getting to know Emmie, she came out to us as a lesbian. Emmie invited us to her home for the first meeting of an organization that would come to be the Lesbian Feminist Union.

We were among the founding members of the Lesbian Feminist Union of Louisville, and we were just on fire with second-wave feminism. I had known only bar life prior to this. I had been working quite a lot in the bars in Roanoke, Virginia, and other places in Virginia. I worked as a bouncer in gay bars. I had done drag professionally.

I pretty much just walked out of the bars and smack-dab into second-wave feminism.

We helped to found the Lesbian Feminist Union, and out of that organization, a lot of things happened really quickly. We came together as an organization, and we got an old house in downtown Louisville. It was an old, derelict, three-story mansion, and we renovated it. We used it to have classes on the main floor: consciousness-raising groups and auto mechanic classes. We taught women about tools, and how to use tools to do simple household repairs. And then, of course, we had the obligatory circles that came out of consciousness-raising, where we would sit around in a circle with a mirror and look at our own cervix. Do you remember those?

FR: We were doing it in 1976 in Kentucky, in that old house.

Mother’s Brew

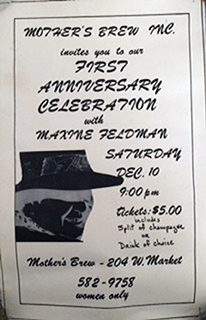

FR: Another thing we did also in a collective way is that we got together, and we sold shares to raise enough seed money to open our own bar. That was on Market Street in downtown Louisville. We called it Mother’s Brew. The logo was a frothy beer mug with a woman’s symbol on the side of it, with a raised fist inside the women’s symbol.

I was the bouncer. It was up on the second floor. You’d go up a long set of stairs, and at the top was a bulletproof, metal door that slid back and forth. It had a little viewing window so that I could see everybody coming up. We rented it from this old mafia don named Joe Polio. Joe said, “I like-ee you girls. You don’t cause no trouble. You keep the place clean, and you don’t cause no trouble. I like-ee you girls.” Bless his heart. He gave me a pearl handled .38 pistol in a sleek black shoulder holster, “just in case,” and he paid off the cops for us too. Any bar operating in Louisville at that time had to pay off the cops.

FR: Anybody, straight or gay, yes. Because Louisville was and still is a major port city on the river, with lots of comings and goings down on Market Street there. We were just two blocks from the docks of the river. There was a secret back door that led out to the roof top of the bar with a fire escape that descended to the back alley. That came in handy whenever the cops would be coming up the front stairs.

I mean, I always knew them when I saw them. They were supposedly plain-clothes cops; but they were clearly wearing clothes that they never wore any other time, trying to look cool. I’d flip the light switch off and on two or three times, and that was the signal for cops. Everybody knew that if you didn’t have your ID, or if you didn’t want to get messed with, or identified, you had to go out the secret back door. When the coast was clear, I’d flip the lights again, or someone would go out back on the terrace to tell folks to come back inside.

Before Olivia was a travel company, it was named Olivia Records, and it was the first women’s music production company. The way that women got the music was through local distributers. We became a distribution center for Olivia Records in the South. We would receive large shipments from Olivia Records, you know, those heavy vinyl albums. We had boxes of them in the back rooms. We sold Olivia records out of the bar. And many of the major artists on the Olivia Records label came to play at our bar.

There was this massive, and I do mean massive – the thing was about twelve feet across – a thing that they called a disco machine. It was basically a glorified juke box, except that it had lights and colors and stuff. The disco machine was in a pit where you’d have to crawl down into it to operate it. There was only room enough for one person down in there to run the lights and the sound, and to play the records. I ended up covering that over, and I built a stage. I was working at a lumber company at the time. Five days a week, I worked outside at this lumber company as the supervisor. I got the bits and pieces of scrap that they would discard, and I built that stage with those.

I’m so proud to say that on the stage that I built, it held up Holly Near and Mary Watkins. It held up Maxine Feldman. It held up Robin Flower and her band. It held up Sally Piano who later called herself… I forget. Gosh, I wonder where she went? Alex Dobkin played on my stage. I think of it as my stage. It was everybody’s, but I made it with my own hands.

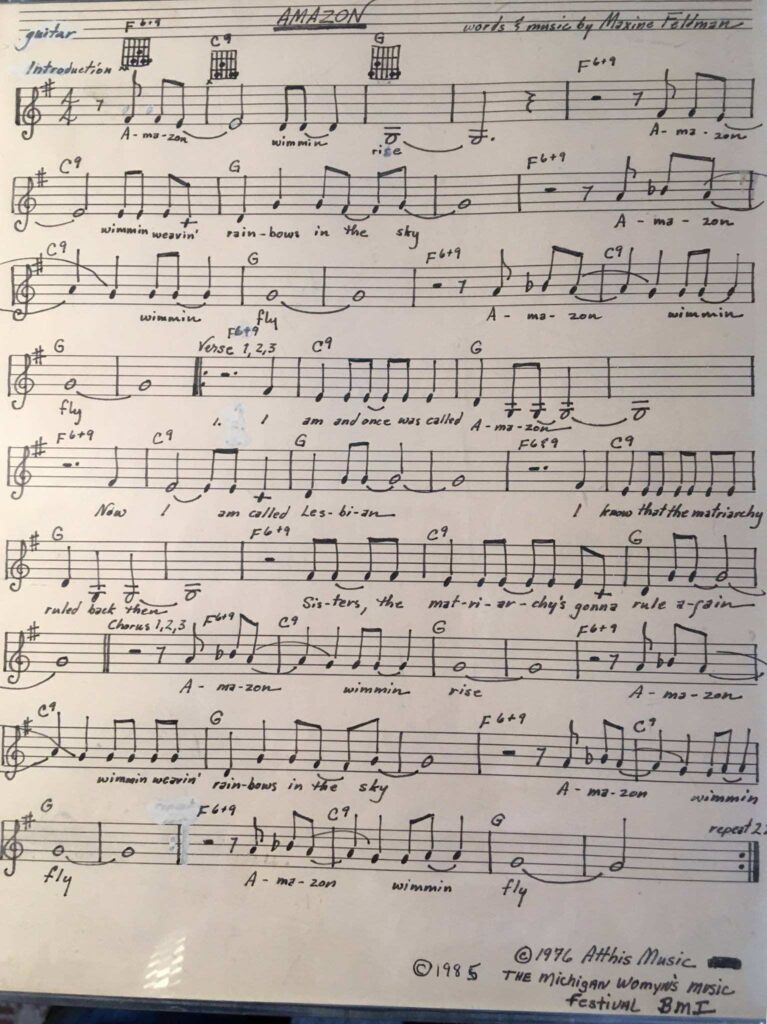

In fact, regarding Maxine Feldman, do you know the wonderful song that everyone sings and dances to at the beginning of Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival? It’s Amazon, and Maxine wrote that song at our kitchen table on Baxter Avenue in Louisville, Kentucky. I’ll never forget that evening. I knew something big was happening. She was sitting there working out this chord and pick thing. And I sat down with her, and back then, I could still play and pick. She’d pick out a little, and I’d pick out a little. Next day she says: “Sit down. I want you to listen to this.” She played me the finished song.

FR: Yes. It’s not like what it’s become. What it’s become is beautiful. And the original version, she wrote it when she was staying with us as she was passing through.

“Amazon”

Music and lyrics, copyright 1976 by Maxine Feldman

Refrain:

Amazon women rise

Amazon women weaving rainbows in the sky

Amazon women fly

Amazon women fly

Verse:

I am and once was called Amazon

Now I am called lesbian

I know that the matriarchy ruled back then

Sisters, the matriarchy’s going to rule again

[Repeat refrain]

Verse:

The Goddess has not forsaken thee

She’s just reawakening in you and me

Heal yourselves, practice your craft of the wise

Amazon Nation is about to rise

[Repeat refrain]

Verse:

Our Amazon witches have returned from the flames

And we will dance in our Moon circles once again

Sisters we’ve known and loved each other in our past

Amazon Nation is rising at last

[Repeat refrain two times]

Last line:

Amazon women rise.

FR: Mother’s Brew served as way more than just a bar. It was actually a community center. It was a wonderful facility.

When you came up the stairs, my face was the first face anyone would see. You had to get through me to get in. Believe me, there were a few fellows that tried to get through me, and they didn’t quite make it. They somehow ended up at the bottom of the stairs.

When you came up the stairs, immediately to the right was the bar area. There was a nice dance floor with room for tables and chairs. It was a big horseshoe-style bar. To the left was a hallway, and immediately again to the left of that was a big pool room. It had two, full-size, pool tables. To the right, down the hallway, we had a lending library of feminist literature and music. And at the far back, we had a room that we used for any woman who had a need for emergency shelter. I think that we were the first battered women’s shelter in Louisville. We had toys for the kids in there, too.

The bar was open on weekend evenings, and oftentimes, during the days, we’d have potlucks or meetings or classes. We sponsored a women’s softball team, and I’ve still got my shirt.

Jade mentioned the nuns. There used to be a group of nuns who would come and sit in the bar. There was one big, round table that was way far back in a corner. It was the least well-lit corner. The nuns would come in their perfectly ironed blue jeans with the creases up the front and the bottom of their jeans turned up just so, and their little flannel shirts; and they would all order Shirley Temples [a non-alcoholic cocktail]. They’d sit back there, and just giggle and sip these drinks with no alcohol. They’d just giggle and sip until it would get late enough that the other customers would start coming in. Then, they would leave. We took good care of the nuns. They were regulars, bless their hearts.

FR: I was the maintenance person. Anything that broke, I did the fixing. Also, I handled safety and security for the women in general. We provided an escort service to and from the parking lot for extra security.

Because it was in a very dangerous part of town, located in what was back then called the “red-light district,” there were a lot of ladies of the evening who would come. The women who were working the streets would come into the bar for rest and protection. Along with some of the other butch women, I organized a series of volunteers to go out to meet women at their cars when they arrived. We would escort them into the bar from wherever they were parked. Now, mind you, this was before cell phones. They had to call the bar from home, and Jade had to take the call from behind the bar. We only had one phone. She’d come over and speak to me. I’d send someone downstairs to make sure that they stayed within my sight when I was up. They would meet the women at their cars upon arrival, and walk with them into the bar. It was even more important for us to walk the women back out to their cars at the end of the night.

Jade was the manager. She took care of the fiscal responsibilities. She did the books, and she also taught herself how to be a bartender. Together, the two of us pretty much did everything. That was it. And both of us were working full-time jobs during the day. We did Mother’s Brew in the evenings and on the weekends. And we had a little fellow – Jade’s son was quite small at that time.

The Guardian Priestess Path

FR: Yes, and it’s a bit convoluted. I grew up pretty much running wild in the mountains and in the woods. My family was so poor that early on in life, I learned how to hunt for our food. My dad taught me how to shoot when I was six years old. I was actually shooting prior to that, but he formally sat down one day, and he taught me to shoot his .22 pistol with a great big long barrel.

We had a nest of bumblebees under the concrete steps under the foundation of our house. One day he brought that pistol out with several boxes of shells and a lawn chair. He stepped out 30 paces* into the yard to place the chair. He took a beer can and put a daub of honey on the top of the beer can, and he set it right in front of the bumblebee nest. Then he walked back out where I was, near the lawn chair.

[*30 paces = approximately 75 feet]He handed me the gun, and he said: “Here, I want you to shoot that bumblebee off the top of that can. Now don’t mess up my can! Just knock the bumblebee off.”

The cool thing about that is, it never occurred to me that I couldn’t. I just did it. By the end of the day, I think we had shot about 96 bumblebees. I only had to replace the can two or three times, and he was more than happy to drink another beer for it.

I went from that to hunting. He started taking me out hunting with him for squirrels and rabbits. We didn’t go after the deer and such. We stayed with the small game, understanding that there was plenty of squirrels and rabbits. Deer were hard to come by… they required a higher caliber of gun than what I would have been able to manage at that age.

Also, there was an understanding in my family and in our culture that existed back then that, very much a blend of our First Nations understanding with old-world Scotts, Irish, and Celtic understanding that you take the least. You take what you need, but no more. If I could get two or three squirrels and a rabbit; occasionally, I would get a pheasant… That would be enough to feed our family and give extra to others, which was also part of our culture.

Early on, I went out every day hunting for food enough to bring meat to our family and to a whole bunch of old, granny women I was very fond of and who were very fond of me. They were truly formative in my upbringing. I knew Granny Burns loved fox squirrels, and Miss Ethel Standard really liked the groundhogs, and Aunt Bernice would prefer rabbit. While I was out hunting whatever I could find, I tried to make sure I got a little bit to take to each one of those elders because they didn’t have as much as we had, and their children were up and grown and gone.

This is my long-winded way of talking about how you become the guardian. You attend to your community. You attend to your elders. I learned to make sure that those elder women got food. I never made them feel beholden. They always honored me in return by: “You know honey, I made a pan of biscuits this morning, and I saved some for you. There’s some apple butter. Would you like to have that?” I’d go off as happy as can be, with a belly full of homemade biscuits, apple butter, and some fresh butter that they would have churned that morning, you know. It was a respectful exchange of caring for each other. And they taught me that. They taught me that.

FR: I have to back up just a little bit to when I was about nine. This is another part of my culture. I was given, and the word “given” is the best way I can explain it. I was given an apprenticeship. Okay, I’m 70, and when I was growing up, folks would watch us and notice what our talents and proclivities were.

Nobody even thought about going to college. I mean, good luck even getting a high school diploma. It wasn’t all that valued. What was valued were your skills. If you had a proclivity for some particular skill, well, then, you were usually… I think it’s an outgrowth of the old, European system of apprenticeship. I was given an apprenticeship to one of my aunts.

She was the local granny woman. She knew all the plants by their common names. Not necessarily by their Latin botanical names, but she knew all the plants. She knew what they were good for. She knew how to make all the medicines. She knew all the songs to sing, the prayers to pray, and the time of year, or month, or week – even day – when it’s best to gather them, when you don’t touch them, when you leave them be, where they were, and how to find them. She also was the one you went to if you wanted to put a curse on someone, to make your neighbor’s cow go dry. Or if you needed a love charm or if you needed to make sure your husband wasn’t going astray with anybody else. My favorite stories I like to tell about my Aunt is that she birthed all the babies.

FR: Yes, she birthed all the babies. I often went with her to be her assistant. Part of being her assistant, without talking about it, she taught me how to set the container. And how to hold that, and to anchor that so that the woman in labor, instead of screaming, after a while, she’d just be [Falcon pauses to breathe deeply and calmly] there.

Without teaching me, she transmitted that to me. I believe that my understanding of the Guardian path came out of my culture that way. My aunt would take me with her to gather the plants. When she was preparing to attend a birth, she’d gather the plants that would make the blood clot, to stop the hemorrhaging. She’d gather the plants that would make the baby come quicker if need be.

I attended to her as she was doing that gathering. One of my jobs was to make sure that no one saw us and that no one disturbed her and that no one found her secret places. How I knew to do that, I don’t know, but I did do it. Goddess, help me, it’s been my struggle in teaching the skills that I do to learn to say in language all that because it was done without language or the spoken word. A language on its own.

FR: Yes. I was her assistant from the time I was nine until around fourteen. I did not learn how to do this. I kind of wish I had. I learned enough. As I said, my aunt birthed all the babies in our county and in many counties around. Oftentimes, the woman would be concerned about her husband wanting to have sex with her before she would be able to receive him; also concerned that, well, if she couldn’t meet his needs, then he might wander off and get his needs met somewhere else.

My aunt would tell the woman to bring her a pair of his soiled underwear, making sure that there was semen and pubes [pubic hairs] in there. The woman dropped off the underwear to my aunt. She and I went out to a particular spot in the woods where we’d go to do this. It was way up, on the side of the mountain behind her house. She looked for a young sapling. Prior to this, she would have gathered up many different plants of medicinal and magical nature.

She always used a copper pot to do this. Her copper pots were special. They weren’t cooking pots for food. They were her medicine pots. Goddess, help you if you touched them. If I was asked to carry them, I could touch them; but otherwise, no. She’d set up the cooking, and it was my job to have made sure that there was kindling and firewood. I had to keep on bringing the firewood, and I had to fetch the water. And I had to make sure that we were not seen or heard, and to make sure that no one had followed us. I’d go back after us to cover our trail.

She’d set up, and she’d cook all day. She would take the young sapling she had chosen prior to this in the woods. She would have brought along with her a rope made of plant fiber that she would have made of certain plants. One of them, I do know, was stinging nettle. She would cook up this gooey, green, gummy stuff. She would dress the sapling with this gooey, green, gummy stuff from the foundation to about four to six feet up. Depending on the size of the man, so to speak, was her aim.

She’d put this gooey, gloppy stuff on the tree, and she’d work with it. She’d sing to it and she’d pray to it. As I’m saying this, I’m mimicking her hands working this green stuff around the bark of the young tree. Slowly but surely, she would lay this tree over, and it would not break; it would bend. Then she’d have wooden stakes that she would have made herself. She would drive in these wooden stakes to either side of the tree and she’d keep slopping this gooey glop on it. She’d start binding that young tree down with a stake here and a cord across it, another stake and a cord across it, until she went the length of the four to six feet. Right in the center were certain knots where she would bind the young man’s underpants onto that tree. She would cover the whole thing with more gooey glop.

And she’d leave it like that, tied down for about six weeks, until the young woman come to her to say, “I’m alright now.” Of course, my aunt would examine her, and question her, to make absolutely certain that she really was all right to resume sex. Then we’d go back out to the woods for another day and a half. She would have brought more plants. Different plants for the laying down than for the rising up of the sapling. I would fetch more water, carry more firewood, and make another fire. I’d cover the trail as we came and went. She would stay with that young sapling until she had brought it right back up straight as it was when she first laid it down. Not a crack in it. No broken nothing. Then she’d take the underpants off, wash them, and give them back to the woman.

FR: Hmmm… I’m not really sure what that means to be an activist. The only thing I can say about that is I am absolutely 100% myself no matter where I am. I do not change. I mean, certainly I am adaptive or adaptable. But in terms of walking through the world, I am who I am, no matter where I am. That might be considered activism, I suppose. I’m just cussed and stubborn. I am who I am, and you have to take me for who I am. For a lot of folks, I think that is activism. There are certainly places where I go that just being myself, it causes a stir.

FR: A butch woman. A witch. A butch witch. Here’s one of my favorite things to do in Southern Michigan where Ruth and I live now. There is a little fairground close by. Twice a year, they have the gun and knife show. Well, I grew up handling guns, and I love knives. I am a knife-maker. I love to go to the gun show dressed just as I am [butch attire]. I walk around, and I talk to people. The first few moments when they’re talking to me, they think they’re talking to a guy.

I keep smiling at them. There I am amongst all the trumpites [people who are far right-wing, politically], being myself. They have to come to terms with the fact that they just had a very pleasant conversation with someone they actually have things in common with, and it was all right. They just had a conversation with a butch lesbian. Someone their beliefs taught them ought to be put to death. They think, “Oh, my gosh. She was really nice.” That’s my kind of activism. And if they don’t like it, well then, let’s step outside, if it comes to it. We can go either way. I am prepared. I don’t go in there looking for a fight. I go in there looking to make connections and to create commonality. Where can we connect? How can we connect? Is there anything we can connect on and have common ground with?

FR: Absolutely. It’s 1975, in Louisville, Kentucky. Two unrelated people could not rent a house or an apartment. If you were a woman, you could not get a credit card without your husband’s permission. You could not open a bank account without your husband’s permission. So, we thought, “Huh, unrelated people.” She sure didn’t want to carry her father’s name or her husband’s name and at that time, I did not really want to carry my father’s name. There was this song that we both liked. It talked about the river of life, how rivers can split, flow apart, and come back together to become like a braided stream.

We decided that River was a name that we both liked. Her camp name was Sam. Her nickname was Sam. Everybody called her Sam, so she chose the name Samantha. Then later, she chose the name Jade because Jade was her favorite stone. It also happened to be the color of the water in the rivers in Kentucky, oftentimes this beautiful, cool, jade green color. She decided to call herself Samantha Jade River.

I actually went to first grade not ever knowing what my given name was.

Falcon River is a name that came to me as a “young’un” [colloquial for youngster] because when I was born, my parents had argued about the name they were going to give me. While my mother was still in the recovery room, my father went and put on the birth certificate the name he wanted, which was not the name she wanted. She absolutely refused to ever call me by that name.

I actually went to first grade not ever knowing what my given name was. I got in trouble that very first day because the teacher called the roll and I waited and waited for my name to come up and it never did. Finally, the teacher come back and told me to grab the front of the desk. I did, and she come down on the back of my knuckles with a metal ruler, saying how dare I, how insolent I was not to raise my hand when my name was called. I said, “I never heard my name.” I didn’t know it. And I kicked her in the shin and ran out of the schoolhouse.

My mother had to walk me back to school the next day to explain why it was that I did not know my given name. Then, of course, the teacher insisted upon calling me that every day in a very divisive way. My school career was not all that great from the get-go. When I got with Jade, having an opportunity to change my name legally to what I had always been called was great. I became Falcon River.

And the reason we changed our names to share a last name in 1975 was that we could pass as half-sisters. Therefore, we could sign a lease on an apartment, or on a house. We could have a joint bank account. I could go pick her little boy up from nursery school in place of his mother because I was his “aunt.” That’s how we got around the laws that oppressed women in 1975.

FR: Yes, I have spent my whole life kicking to the curb the very idea that a woman cannot wear whatever clothes she wants to; that a woman can’t do, and accomplish, and live, and have any occupation that she wants to. I will not be and am not ever comprised, defined by, or held back from doing anything because I’m female. I wear the clothes that I want to wear because they suit my chosen activities and the things that I enjoy. Some women are great at riding a horse with a flowing skirt. I admire them. I can’t. I get it all hung up in the stirrups. I grew up climbing down in caves. Skirts don’t work well for that. Some women are excellent at it, and again, I applaud them. But I’m not one of them. I’ve been wearing blue jeans and boots from the time I was tiny until right now. I hope to be buried in them.

FR: Have courage. Don’t let anybody tell you that you can’t do anything. Get up and do it. And be proud of yourself. But here’s the deal: being butch is not masculine. I don’t want to be a man! I’m way better than any man. I represent the full spectrum of everything that a woman can be. I’m fierce. Have you ever known anything more fierce than a mother bear protecting her cub? No. Have you ever known anything more fierce than a mountain lion mama protecting her babies? No. Do they call them butch? No. Be you. And don’t let anybody else’s definition of what it is to be a woman affect your own personal definition of what it is to be a woman. It’s for you to inhabit fully your powerful female body.

FR: Blessed Be.

FR: There is nothing about me that’s masculine. Every aspect of me is female. At the cellular level, I am female. I was born female. I live female. I bled. I’ve been pregnant. Albeit it was against my will. I did not choose it, but many butch women do choose it. And the ones that do, make excellent mamas. They are not daddies. They are mothers. I and other butch women like me, we embody part of that full spectrum that is womanhood. These are my jeans, my boots, and my T-shirts, because this clothing serves my needs for my chosen activities and my chosen occupations. Not because I want to be a man. It’s got not a damn thing to do with that. It’s because I choose to live free. I am a gender abolitionist. I choose to live free. I choose to live defiantly as a free woman. And I claim my space every step I take. And don’t tell me that I have to be a man to do that. Oh, no, I don’t. Men mean nothing to me. I’ve got nothing against them; but I’ve got nothing for them, either. My motto has often been “lead, follow, or get the hell out of my way.” I am a sovereign woman and I create female sovereign space wherever I go. Blessed Be.

FR: My father and all of his siblings were incredibly fertile. I grew up in the southwest corner of the state. My father’s last name was Coleman. There are not a lot of people by the name of Coleman in that town anymore. I have a lot of cousins who are still there, and my last surviving uncle still lives there.

In my father’s generation, one of my father’s sisters had 12 children. Another had 14 children. Another had 16. Some of those women married men who were cousins. Not close cousins. Families intermarried because up until my generation, a lot of folks never left the Appalachian Mountains.

I can trace my father’s family line back to Jamestown to the very first English settlers that came into the mountains. The gentlemen were the first to come. There weren’t a lot of ladies that came with them initially, and the men took wives among the First Nations people. I come from that cultural milieu.

FR: It was a common hunting ground for a lot of folks. You’re looking at, I don’t like this word, Cherokee. They called themselves Tsalagi and also the Cree. My father’s mother come out of the mountains of Virginia and North Carolina. On my mother’s side, her father was of Scotch descent. Again, her descendants came over fairly early through that part of northern Ohio and southern West Virginia into the Appalachian Mountains. I mean, I am pure Appalachia. You can’t get any more pure Appalachian than me. When I say this is the face of Southwestern West Virginia, folks know that when they see me.

If I hadn’t have been a wild thing, I probably would have taken the herbalist

and midwife path as well.

FR: Yes, I told you about being an assistant for my aunt. If I hadn’t have been a wild thing, I probably would have taken the herbalist and midwife path as well.

FR: Yes, exactly. I’m about to turn 70 on October 5 [2022]. My dad was born in 1905, and he was 48 when I was born. My grandfather, his dad, was born in 1863. It’s amazing to think that in that short time, so many of the generations of this country have spanned through the lifetimes. When I was growing up, there were still widows of confederate soldiers living in our town. To most folks these days, the confederate war was far in the past. For us elders, that was our grandparents.

FR: I think that what happened was that Jade and I took our focus from the LFU to running and operating Mother’s Brew. Both of us were holding down full-time jobs, and we had a little boy to raise. We devoted our energies to making Mother’s Brew a success and trying to provide a meeting place for a number of different women’s groups.

FR: I think that it ended about 1979 or ‘80. It was a short run. It was an intense run. Jade and I had a lot of stuff going on with raising Jade’s little boy, and with both of us working full time. Also, I was doing my best to get into the trades. And it was a rough road. We ran up against just having too much going on. And on top of that, I really wanted to get sober. You can’t get sober running a bar. In fact, my desire to get clean and sober was part of the eventual demise of our relationship because Jade wasn’t really supportive of that. I came from a family of profound alcoholics and alcoholism. I’m a survivor of domestic and childhood abuse. I didn’t want to perpetuate that in my own life. I wanted to make that change, and I wanted to address my issues.

FR: I don’t know if this was the beginning of RCG, per se. I wish I could count that year, the first year that Z. Budapest took that little yellow book to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. We were there. And we got that little yellow book. It had to be 1978 or ’79. She had women circling up. From that first ritual, I was, like, “Yeah!” I mean, my first experience with hundreds of half-naked, dancing, drumming, ecstatic women in the woods. That was it. Then I knew what I was.

We went home with our copy of that little yellow book, and we started having Moon circles immediately after we got back. All we had was that little yellow book. Jade and I started priestessing to our community.

In 1983, we left Louisville, Kentucky, and moved to Wisconsin on the run because Jade’s ex-husband was trying to take her son from her.

FR: Sirani Avedis. She was of Mediterranean descent. If you want to fact-check that, I gave Professor Bonnie Morris my original copy of the first Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival flyer, and Sirani’s name is on there. Bonnie Morris may know what became of her. Maybe Toni Armstrong, Jr., also knows something about her. Toni played music with Kay Gardner and Alix Dobkin in the early years.

[Per Bonnie Morris, PhD: “Sirani had several names, identified as Armenian. And she was the cover artist for the issue of Paid My Dues, v. 3 no. 2 (1979).”]The Guardian Priestess Path

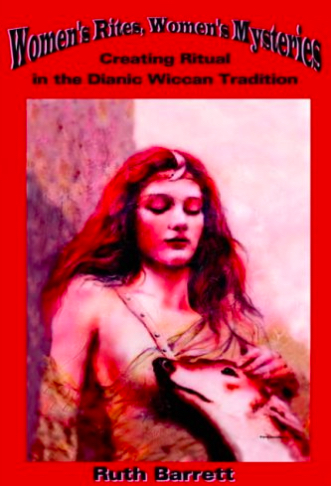

FR: We did write about it in Ruth’s book, Women’s Rites, Women’s Mysteries: Creating Ritual in the Dianic Tradition.

[Women’s Rites, Women’s Mysteries: Creating Ritual in the Dianic Tradition by Ruth Barrett, published in 2004, was republished in 2018 its third, expanded edition as Women’s Rites, Women’s Mysteries: Intuitive Ritual Creation, with Tidal Time Publishing LLC.]

Guardian facilitators offer their service from the perimeter of the circle, energetically, that is, with women’s magic energy, supporting the ritual facilitators who work within the circle. I was ordained in 2000 as a Dianic Priestess of the Guardian Path, dedicated to a magical partnership model that collaborates with other ritual facilitators to insure a safe and powerful ritual experience for the participants.

FR: I will tell you about the context of it in the women’s spirituality movement. Naming what I do came out of the early stages of development of RCG’s Cella Program, a priestess training program [offered by RCG’s Women’s Thealogical Institute.]

There was a group of women who didn’t quite fit in any of the established pathways. A lot of the women had been trying to get me to come to the priestess gatherings, and to teach over the years. I had fairly consistently declined for my own personal reasons. After declining for several years, I acquiesced. I did start teaching a few workshops about energy work, called “energetic work,” and doing interspecies communication work. That’s what I called it then and now because the core of energetic work, the way I teach, it is firmly rooted in tree lore.

This is aligning energetically with the trees, with the Earth and the elementals. And the Spirits – not the humans, the other folk who inhabit our world, who dwell primarily in the forest. That has always been my path.

In the early years of the development of the Cella Program, I’d been asked by a number of women, and of course, one of them was Jade, to teach at their gatherings and to teach in their program.

FR: Oh yes. Years. Like from 1983 to the mid ‘90s, or maybe early ‘90s. I would say at least a decade after we had been broken up. I agreed to teach a workshop with one of the RCG priestesses of blessed memory now, Deb Trent.

FR: Oh, yes, many years ago. Probably almost 20 years ago. She passed not long after Ruth and I got together. When I taught that workshop, a number of women had a positive experience, which had a profound effect on them because they got to do what they were innately talented in doing.

After that, three women came to my house one evening: FireHawk Stewart, Gigi Vale, and Vick Tree. They asked me if I would please join them in forming a group within RCGI. I can’t recall the term they wanted to use initially, but it wasn’t guardians. I have some documentation on this somewhere.

They wanted to study more. They wanted me to create classes and a pathway for them. Unfortunately, all of the women in RCG at this time who didn’t feel that there was really a place for them were butch-identified lesbians, myself included and it became a program mostly for butch women. I wasn’t comfortable with that. I want to say that right off the bat.

FR: I’ll come back to that. Anyway, I agreed. I agreed because those three women came to me, and they took the trouble. They got up their courage because they knew how I felt about it. They came to my house, and they asked me to please help them. I said, “OK,” and I did. We began working together.

I really felt strongly about the word “guardian” because I felt that what we did energetically is to provide both containment and protection in a magickal sense. For the folks to come who may get a chance to take a look at this documentation, I’m hopeful they’ll see that to be a Dianic witch, and to do your rites outside, it is dangerous. We need to talk about this. Just to be a witch is dangerous. Just to be a group of women hanging out, outside at night underneath the full Moon or the dark of the Moon, is dangerous.

We began to meet together, and we talked about what it is each of us women normally feel called to do when there’s a ritual. What we all came up with was that we could serve at center if we were asked to. [In the center of the circle where the ritual takes place, especially in the role of a primary priestess, who is responsible for holding the energy of the rite.] What we felt called to do is to patrol the perimeter outside of the rite to make sure that the rite happened with no harm to any of the participants. It was more important to us that the work be done and to go forward than for us to partake of it.

We felt strongly about the importance of setting up the space first magickally. At our larger rituals, especially at our Daughters of Diana (DOD) Gathering, which Temple of Diana has been holding now for several years, those of us who serve as ritual guardians start preparing that ritual space hours ahead of time. We set the container and make sure there are protective wards in different places, in different directions for different reasons.

I began working with those women. By the time the RCGI Gathering of Priestesses happened in May of 1999, Z. Budapest came. Ruth Barrett was working at center along with the RCG priestesses. It was me, FireHawk, Vick Tree, and Gigi serving as guardians in each direction, placing ourselves in the portals.

A big part of the guardian work, once the container is set, is to maintain the container; and also, to send very specific, elemental, energetic support to the priestesses who are invoking, or not priestesses necessarily, but those women who invoke. And also, to send energy to those women who are facilitating and embodying enactments. This particular ritual was also a ritual of ordination. There came a particular moment when the High Priestess Ruth Barrett turned to Z. Budapest and asked her if she had ever been ordained. Z said no. Right there, on the spot, Ruth took Z through Dianic ordination.

FR: Ruth presented Z to the four directions with guardian energetic support, which literally knocked them on their butts. Because we just … [Falcon made a guttural sound with a sweeping gesture forward and a beaming smile]. It was a very wonderful and proud moment!

It was such a wonderful moment that shortly after that, I became consort to Ruth Barrett. That’s a whole other story. I ended up moving away from Wisconsin to California to start a new life with Ruth, and to become a member of the Circle of Aradia.

Initially, guardian path work was not well received at Circle of Aradia (COA). I say this in the interest of herstory. I feel that I was not terribly welcome at COA in the beginning. I think it was because I’m not traditionally female. Until I stood up in the way that I have in the last many years, most butch women do not and did not feel comfortable coming to the women’s circles because we were not traditionally feminine in our appearance. If you are an energetically astute or a sensitive person at all, you can feel that lack of welcome, which is a light way to say it. I felt this like “boom,” a brick wall. I’m coming in all full of love, yeah, spiritual community, and let’s go – and no. [Falcon smacks one hand with the other.]

Of course, there were other issues involved. Some folks may have had a reaction to seeing Ruth and me together. That’s completely understandable. So, it took a while for women to accept the guardian path work as a valid path of service and ministry.

The other thing that’s important to note is that as I mentioned earlier, the RCG style of guardian work consisted of a place to channel butch women. Early on, Jade had said that “butches are guardians and femmes are priestesses.”

FR: That’s a quote. Please don’t get angry with me. It is a quote.

FR: As if women who present in the traditionally feminine way do not have the same strength and skills as butch women. To me it’s internalized sexism. It’s internalized homophobia. The finest guardians that I know at COA are not butch lesbians. The finest guardians that I know at COA are actually heterosexual women. They’re not lesbian at all, and their presentation is unique unto themselves. And I am so proud to stand with them and serve with them.

As has always been true with Ruth Barrett, her training of women and the society that we want to build is that each woman should be free to choose to serve in whatever manner really speaks to her.

There was a lot of drama with the RCG approach and with what eventually became the Temple of Diana approach to guardians. Temple of Diana grew out of Ruth’s work with COA, and also Temple of Diana grew out of our inability to continue to work with RCG. We wouldn’t go along with what we considered a sexist tradition.

FR: Never. In our mystery school called Spiral Door [Spiral Door Women’s Mystery School of Magick & Ritual Arts], everybody gets the same training. Once everyone goes through the same, basic coursework and training, then you can choose what you’re really called to.

FR: Yes. That’s our way. So, they [butch women in RCG] would not have gotten any training in invocation or spell-craft or all the skills that we require of our Temple of Diana priestesses to be able to facilitate our rites.

FR: I’m not sure what you mean.

FR: My spirituality was awakened and informed by being in women’s community. Specifically, what I’m thinking of is my first Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. I went when I was 23, and I was already a lesbian. I came out when I was 16. And I had been a butch. I had been a bar butch. I was a Drag King. I was a pretty rough and hard character, arriving at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival as a freshly-minted feminist, I thought. You know, I was getting there.

Even though I’d had enough feminist experiences, I thought I was ready to go to MichFest. Yet it absolutely changed my life! In fact, it set the course of my future to be in pure women’s space. True women’s space. To be outdoors and to take off my shirt in front of a couple of thousand other women who had also removed their shirts in defiance of men with guns and telescopes that were lined up on the road surrounding the MichFest Land, that for me was the first experience of being out and proud, and dancing and drumming, and just feeling ecstatic. My memory of it is more of a feeling than an actual “this happened, then that happened.” It’s the feeling of really touching into my own soul, my own women’s soul, and touching the souls of all the women around me expressing our ecstasy. It formed and shaped the rest of my life, and it still does.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Falcon River: Oral History in LBGTQ Religious Archives Network

https://www.rcgi.org/

https://www.circleofaradia.org/

https://www.tidaltimepublishing.com/women-s-rites-women-s-mysteries

Jade River, “Mother’s Brew and Louisville’s Lesbian Feminist Union,” Sinister Wisdom 109 (Summer 2018): 31-34.