Diana Rivers: From Atheist to Pagan

Diana Rivers goes from atheist to pagan while serving cakes for the Queen of Heaven.

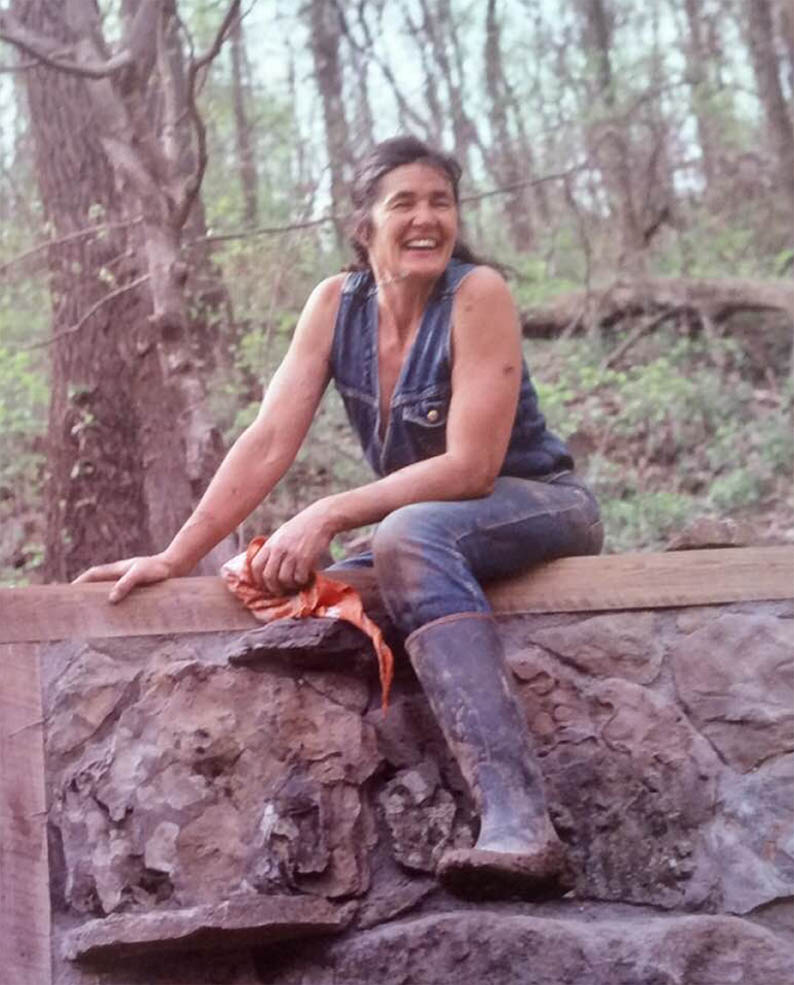

Diana Rivers dove into the deep end, swimming into her new life, upstream and against the current, excitedly. She was now free to explore and expand in ways she’d never dreamt. We sat together on Diana’s 88th birthday in front of the 50-foot-long stone wall she built by herself as the back wall of her house. On this crisp October day, I marvel at her beauty. After surviving a near-fatal stroke seven years ago, in December 2015, she doesn’t miss a beat. Vivacious as ever, Diana is a mystery: serious, purposeful, even a bit intimidating.

Leaving a 20-year marriage after bearing three sons, Diana arrived in Arkansas divorced and alone in 1972. At 38, Diana was an atheist with no affiliation to anything spiritual. She wasted no time. With a young boyfriend, she started Sassafras that same year, originally a countercultural community of both women and men, mostly hippies. There, she flirted briefly with Buddhism, yet found nothing there to affirm her female self.

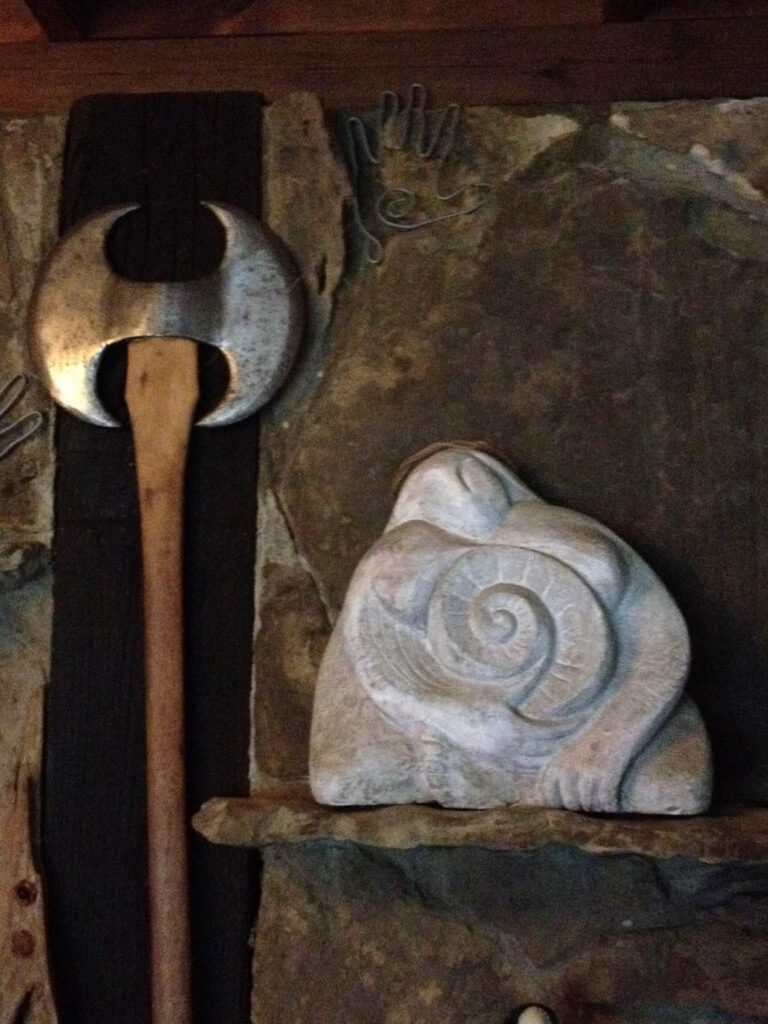

In a few years, most of the women at Sassafras left and came out, or they came out and left. Following an explosive meeting, Sassafras became women’s land. While there, Diana met a younger, woman lover who was involved in spiritual circles. Diana didn’t seek anything religious. However, she was drawn to drumming circles where she could stand outside in the forest with other women in the natural world. Though not the high priestess, she helped to keep these sacred circles going for a long time. A lifelong artist and sculptor, Diana also began to create full-bodied Goddess statues. She carries her favorite, Goddess Rising, to every event.

Born Diana Smith, she became Diana Folley by marriage, and she wanted a new name of her own choosing, a name that would reflect moving into her new life and a new state. She loves the name Diana, chosen by her parents. She said that she would have chosen it even if they hadn’t because Diana is the goddess of the forest and wild creatures. She wanted to change her surname to something more earthy, but not so new-age that it would embarrass her later on. She considered Forest and Rivers, and she decided that Rivers naturally flowed with Diana. Now she loves seeing it on her published books.

“I didn’t really have a Christian upbringing. Yet for some reason, when I was 12, my mother decided I should be baptized. I don’t know why. She had never gone to church herself, but her decision pushed me into a Bible class on Wednesday afternoons.” Diana rolls her eyes as she remembers going to two sessions before being thrown out. She recalls it was caterpillar season. She was bored, and she put caterpillars down the necks of girls sitting in front of her with hysterical results. The second time, she brought in a baby robin and worms. She was asked to leave the class before she did any major harm. “I don’t remember if I ever did get baptized. But if I did, it sure didn’t stick!”

Diana Rivers recalls attending a course at the local Unitarian Universalist Church called “Cakes for the Queen of Heaven.” This led her to immediately begin looking for goddesses in the Bible. For the last class, Diana wrote, “Sisters, Let Us Remember,” a piece of writing which was passed around the class, each woman reading one line. This became the first performance piece for Goddess Productions, a traveling reader’s theatre collective that Diana started in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in the late 1980s, ongoing for five years into the early 1990s. It began with just Diana, but expanded to a collective that also included Vick Kelley, Bea Howard, and Path Hennon.

Afterward that experience, Diana wrote several more scripts for reader’s theatre and found ways to perform them. At first, she did it on her own. After a while, a collective of four was formed. They would go to women’s communities in different places in Arkansas, Florida, and Alabama, enlisting readers, drummers, dancers, and if they were lucky, a flute player. After a couple of rehearsals, they would put on a show. They could do it so quickly because they were working from scripts and no memorizing was necessary. Some of the titles were “Nothing Tame,” “Dancing the Spiral,” “She is Born,” “Voices,” and of course, “Sisters, Let Us Remember.”

At one point, the University of Arkansas decided to have a weekend-long, women’s conference and festival, and they asked for proposals. Diana recalls, “my friend Georgia and I wrote a wonderful proposal for a women’s art show that we called WomanVision. I think it probably sounded too radical for the students. We used the word goddess or talked about making altars in the home, and the students turned us down.” (However, Diana did end up curating their women’s art show, and she continued that for the full ten years that the conference took place.)

“Angry and hurt, I was in Kansas City, visiting my friend, Laura, and stewing about this refusal,” Diana said. Laura asked Diana, “Why don’t you do WomanVision here in Kansas City?” Diana said, “I don’t live here, And besides, where would we do it?” Then, Laura took Diana to a place that accepted her idea.

Diana Rivers and her friend Laura formed a collective of friends. For the next three years, from 1991 to 1993, Diana spent part of the winter in Kansas City doing WomanVision, which was very successful, each March. A dream come true, Diana says “the WomanVision art show became the womb for every sort of woman’s expression: spoken word, music, dance, and whatever else we could think of, including Goddess Productions performances, of course.”

WomanVision was followed in a couple of years by Matriarts, another women’s venue for art and performance, started by another friend, which took place for about three years. After that, Diana had a longing to see women-centered art on the walls. She kept talking about goddesses, angels and Amazons. One evening, after everyone came in from a full-Moon float on their local river, Diana asked her friend Vick if she would like to join her in producing a goddess festival. Vick enthusiastically agreed. Neither one knew what they were signing up for, but the Goddess Festival, as it was called, did happen. It started in 2009, with Diana at the helm for about five years. It is still going in 2022. It used to be a month-long festival, and now it runs part of a week with a Spring Equinox ritual in the middle of that time. Diana was shocked to be able to hold the Goddess Festival in the heart of the Bible belt.

In addition to performing, Diana had written contemporary short stories. She had no goals of writing a book until one hot summer day, sick and with a fever, she went to a friend’s house in town to rest. While trying to sleep, a fantasy (or perhaps a vision) came into her head about a woman walking to the ocean to drown herself. Sair (Sairizia), after being gang-raped by guards, decided to manage her own death. Women who called themselves the Hadra pulled her out and saved her. Sair ended up living with them and learning their ways. Even though Diana felt ill and weak, she wrote down this fantasy that became the first page of Journey to Zelindar. This was the beginning of the Hadra series of books. Though Journey to Zelindar was the first book of the series to be written in 1987, it ended up being the last book of the series, chronologically.

In August, a few years later, while Diana still lived at Sassafras, the resident women had all gone to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, leaving her alone there on 500 acres. She started writing. She wrote and wrote, even being awakened at night by an inner voice telling her a list of names, about a raft trip in a flood, and a method for making cloaks. She continued receiving messages from that inner voice. One and a half weeks later, she had the very first, rough draft of her book. It took seven more years to get it finished and published.

Following that came Diana Rivers’s famous Hadra series about women with extraordinary powers and mind-reading abilities: Daughters of the Great Star (in 1992); The Hadra (in 1995); Clouds of War (in 2002); The Red Line of Yarmald (in 2003); and The Smuggler, The Spy, and the Spider (in 2012). Diana describes her life as full of contention because the Hadra were being hunted, and they needed to learn to live together without conflict. After each book, Diana swore she would not write any more Hadra books. Yet they continued informing her in both waking consciousness and through dreams until she could not ignore them.

One day, as she was putting away her clothes, an imaginary little girl started speaking to her about the “gray people,” who were weavers enslaved in a cave called the Gray Place. Diana said that she didn’t want to hear about this terrible gray place, and that she was not going to write this wretched story. But Kitra, who becomes a character in this book, is a very persistent child. Kitra persuades a young Hadra named Nhazul to help her break open the cave to save her friend Tulli. This becomes the book Her Sister’s Keeper (in 2007), which Diana has dedicated “to all of those in this modern world still living and working in conditions of slavery.”

Diana also wrote City of Strangers, a book that is not part of The Hadra series, as well as a collection of short stories written over forty years, called Snake Memories and Other Stories (in 2015). Her latest, published book, Dancer for The Goddess (in 2016), was one of her first books, but she had abandoned it when she couldn’t find a publisher. It has since been published by Goddess Ink.

Diana Rivers was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Awards, and she won the Golden Crown Literary Award for Speculative Fiction.

Diana feels sorry that she never got to build a goddess temple in town; however, she boasts of a beautiful space for Goddess rituals in a cedar grove on the women’s land where she has been living for almost forty years in the hills of northwest Arkansas. Diana has been exploring the questions of ritual and of a mother’s love as the driving engines for evolution for a long time. She includes aspects of this in her novels; stories; goddess performance pieces; personal reading of history and anthropology; and in many discussions with her friends and colleagues. Diana is committed to keeping the spirit of the Goddess alive, and she no longer wants to lead. Now, she is quite content to simply participate and follow the rituals, which remain very central to her blessed life as an authentic pagan Goddess.

The story is based on an unrecorded interview by Debra L. Gish, focusing on getting at Diana’s real-life experiences as an activist, artist, performer, and the acclaimed author of several books, each exemplifying her spiritual quest to meet, know, and spread the word of the Goddess within us. Photos contained in this story were provided by Diana from newspaper articles, photos, and programs from various events. Debra asked Diana to describe in detail the different moments that shaped her new life: from being a self-proclaimed atheist to a raging pagan up in the hills of Arkansas. Gish interviewed Diana Rivers in her OLHA home on October 17, 2019, which was Diana’s 88th birthday. The story has been reviewed and approved by Diana Rivers.

See also:

SLFAHP written interview with Diana Rivers by Rose Norman on May 24, 2012.

Debra Gish, “Diana Rivers: From Atheist to Pagan,” Sinister Wisdom 124 (Spring 2022): 41-45.

The recorded interview of Diana Rivers by Rose Norman, on May 24, 2012, done at Womonwrites, the Southeast Lesbian Writers Conference, held in a state park in Georgia, is archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubinstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. The audio recording of that interview in online at Duke.

Diana Rivers, “Sisters, Let Us Remember,” Sinister Wisdom 124 (Spring 2022):5-18.

Merril Mushroom, “Arkansas Lands and the Legacy of Sassafras,” Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 36-42.

Allyn Lord and Anna M. Zajicek, The History of the Contemporary Grassroots Women’s Movement in Northwest Arkansas, 1970–2000. Fayetteville: 2000.