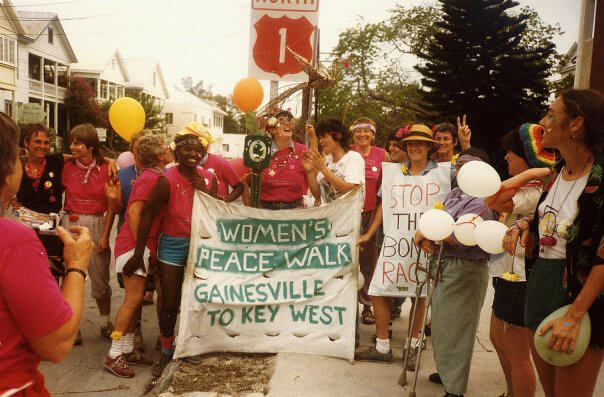

Corky Culver and the Women’s Peace Walk, 1983-1984

Edited by Corky Culver and Marie Steinwachs from taped interviews of Corky Culver by Marie Steinwachs in 2021

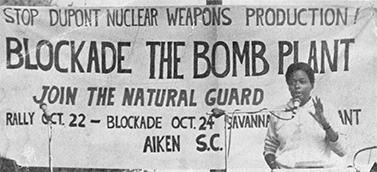

On October 24, 1983, several Gainesville, Florida, women joined a national blockade at the notorious Savannah River nuclear bomb plant near Aiken, South Carolina. Corky Culver was one of the arrested and jailed activists who refused to provide law enforcement with names, becoming internationally known as the “Jane Does.” During 16 days in jail the women spoke with the media and planned their next action – the Women’s Peace Walk – which launched from Gainesville in December, bound for Key West, 540 miles away.

The Peace Walk was life-changing for the participants. Corky’s transformation is detailed in her poem “Sunday Night Service at the Bamburg County Jail After the Savannah River Nuclear Bomb Plant Blockade” and the 2021 interview. Corky acknowledged the leap of faith that the Peace Walk required. “We didn’t have money backing . . . .We had our sleeping bags and our blow-up air mattresses, our clothes, and our food.” Corky described how the feminist process of circles and consensus guided all decisions. She used details from her journals – and humor – to recount the hardships as well as the great surprises that they experienced along the way.

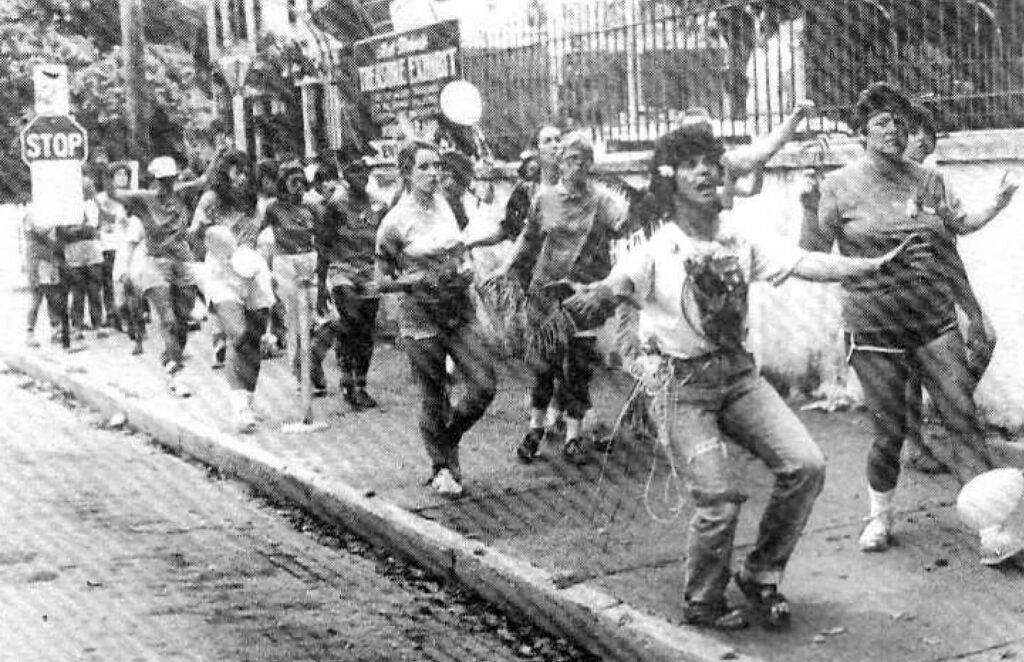

The Peace Walk culminated at the U.S. Navy’s Caribbean Command HQ surrounded by media, tourist crowds, and loudspeaker busses. The women spun an elaborate, colorful yarn web symbolizing the power of networking and the interrelatedness of all life. They climbed the iron bars, lifted the web until it caught on barbed wire above the gate, then draped down and gently enveloped the Naval Command’s entrance.

From Protest to Jail to the Women’s Peace Walk

It was December 17, 1983, when we took the first steps toward Key West from Gainesville, Florida. I wasn’t a main organizer of the Peace Walk, but I was one of the six from Gainesville who had been in jail in South Carolina for the successful Savannah River Nuclear Plant Blockade [October 24, 1983]. That was a really big protest, and it resulted in the plant having to close down a few dangerous reactors and repair them. And the people in the local communities wanted us to be there. It’s hard to go against the big corporation that’s running your town.

Anyway, while we were in jail, we had agreed to give our names only when, by consensus, we had all agreed to get out. And it was true that by staying in jail as Jane Does, not giving our names, we were getting a lot of press! We were on NPR, and there were newspapers coming in. It wasn’t a typical jail experience at all. Well, it wasn’t what I presume would be a typical jail experience. For one thing, we had the media spotlight and international attention, so we weren’t as likely to suffer any abuses. In fact, the only time I felt we were harshly treated was when one of the jailers played music all night long, repeating the same song, so we couldn’t sleep. I think we lucked up in that the sheriff was one of the sympathetic locals who agreed with us.

There were so many of us that we filled the whole women’s floor of the county jail, something like eight cells for ten women, so the sheriff ended up opening the doors to the individual cells within the block. We would use one cell for a workshop on dreams, for example, and another back cell as a place where women could go to the bathroom in some sort of privacy. When we were first locked in, the stark reality of metal bars, metal bunks, metal toilets in the open, and harsh light was frightening! Then, I took my red jacket and draped it over the light fixture, bathing the cell in a soft pink. Having my rose-colored lens in place improved my outlook! We decorated the walls with drawings and made sculptures from the Wonder Bread we wouldn’t eat. Don’t get me wrong, jail was not fun. The beds were hard and the food sucked, yet occasionally there would be a package from Barbara Deming with cookies. [Deming was an internationally known peace activist then living on Sugarloaf Key, which her friend Blue Lunden was turning into a women’s residential community.] We were determined to be of good cheer.

After a couple weeks in jail, many wanted to get back to Gainesville and our lives, but we were blocked from consensus by a few who didn’t think we should ever give our names until all war was ended. I had this vision of myself with my long gray hair, sitting there forever. I could just see it!

We did a meditation together for the first time, and in meditation we put a blanket on the floor and pretended it was grass. We sat around it, and we got into a deep state — truly we were in another part of our brain — and when we started talking, we were talking not from the left brain that makes decisions and is real rational. We were from the right brain, kind of imagistic, and people would say, “I see green trees and a bird’s nest.” Someone else saw some tin cans. I mean, we were just saying whatever floated to our brains, and we were open to that. It was like sharing dreams.

Somebody thought of a stream, and we got the idea of a walk, which would be like a stream, a way we could keep speaking and testifying for our issues, which were peace and disarmament and health! In other words, we could continue working against war without staying in jail until my hair was four feet long! So that’s what we did — we decided to go on a long walk. One of the group knew someone who had done a peace walk in upper New York State [Sugarloaf women Barbara Deming and Blue Lunden]. So we had that model, and Barbara Deming and Blue had gone to jail in a protest, too.

I had been in some gay pride events, and I was used to being in the streets. We marched for Martin Luther King Day and Take Back the Night, and so it felt comfortable and usual for our crowd, in a way, to be out walking. I don’t remember how we got to the idea of going all the way to Key West – the length of Florida! That’s a long way, I tell you! But that’s what we decided to do, and then we gave our names and got out of jail. They sentenced us to the sixteen days we had already served. [Read more about the South Carolina peace action in this story originally published in OLOC E-News, December 2022, “Jane Does, Jail, and the Gainesville Peace Walk.”]

On the Road: First Steps on December 17, 1983

When we got home, we told a few people what we were doing, and it just kind of took off! It was still in a dream state, in a sense, because we didn’t have this giant budget. We had $180 or something, you know? We just had enough to get going. We weren’t thinking where we would go or how we would live. We were just going to take off, and we had a banner – Women’s Peace Walk.

[On the first days of the Peace Walk, Rena Carney recorded interviews and songs. Here is a song sung in the Gainesville plaza, where they began the march. As they were walking, Rena recorded a brief audio interview with Sugarloaf peace activist Blue Lunden.]

We had a van that went with us, but we did not have an outside support group. I mean, our friends knew we were doing it, and women could go and come. There were, I don’t know, about twenty of us to start with. We headed down the state, and along the way we got in touch with peace groups and church groups. Before the internet, there were phone books and dial phones! It was like walking into the dark, absolutely! It was deliciously like that because we were open to the experience.

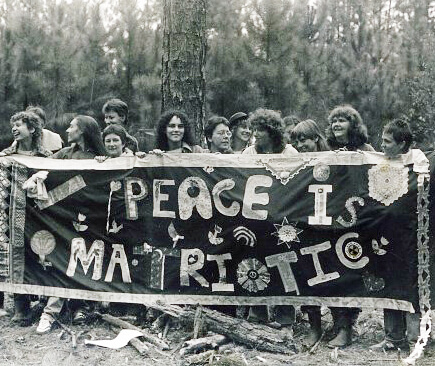

We talked the first night about what our goals were. This was at the time when wretched things were going on in Central America. Maybe all times are a bit like that, but the United States and others, totalitarian forces, were holding down the people, and there were death squads. So we agreed that our mission was partly about Central America, and partly about other issues, like disarmament, and partly about feminism. We had a lot of discussions. Some of us weren’t political and didn’t know a lot about the progressive politics of Central America and other issues.

We all aspired to a kind of feminism that included peace. We weren’t just focused on the issues of reproduction and how to get along with your man. Most of us were lesbians. I was really more interested in meditation. I can remember saying that night in the first circle, that with each step I hoped to just love the Earth and be appreciative of being out in her air and walking.

Two circles a day to talk

We had a lot of different mindsets, and that, of course, happens in groups. The first night we were out, we were at somebody’s house, so I don’t remember any issues. But the first issue arose when we woke up the next morning. Nobody wanted to wake up at the same time! Some people’s bodies, their bones, their breath, their deep being, they absolutely do not think it’s appropriate to get up before ten o’clock in the morning! They believe it’s a jarring travesty to the body to get up early. Then some feel like every second counts, that if you have a grain of virtue in you, you will be ready to go by eight o’clock. Of course, that means we will be getting up at six-thirty! That’s how they saw the world–you’ll breakfast, clean up, and get on that road at eight!

We found pretty quickly that we needed to have two circles a day to talk about things, so we had a morning circle and an evening circle. Twice a day we would go around the circle and people would say their feelings, and grievances would be aired. It made all the difference because everyone felt heard. That was a beautiful and brilliant thing that we continue to do in so many groups today.

One of the other big decisions was whether we should walk through malls and crowded areas and try to interact with as many people as possible about our issues. At the time, a lot of people were interested in peace and some thought we were a bunch of lezzie commies. Some of the women were worried about the perils of the road and wanted to walk the safest way. Then some people – me – wanted to walk along the ocean because it was beautiful, and by doing that we would be honoring the beauty of the Earth. I wanted it to be more of a prayerful event. We ended up walking along the ocean!

Cracks in reality

Women joined the Peace Walk because, in addition to its political mission, it had an element of adventure and fun, and because sterling, good women were going. We were a good bunch, idealistic and artistic, and so who wouldn’t want to go with them! Is that vain? Anyway, it certainly wasn’t just privation! I was in a good mood. I had fallen in love — or flirtation anyway – and I was happy to be out there.

There were always one or two women driving the van, and they were responsible for meeting the group for lunch and bringing food. They were also responsible for finding that night’s resting place. On my first day as support I had an idea. I was driving by a long stretch of beach that had no houses and no beach access, just thick brush and shrubs. I thought there might be a path through there somewhere, so I took it upon myself to drive up and down this mile-long stretch until I found a path. I parked on the side of the road, followed the path to it, and thought, “Glory be! They’ll love this!” It certainly wasn’t just privation!

On a little sand peninsula at the edge of the sea oats and the dunes was a nice, big beach and not a soul around! I went back to meet the group for lunch and said, “You’re almost there. I found a place on the beach. You have to go on a path.” A lot of them worried whether this was right, but I said, “I think it’s going to be good! I think it’s just the break we need.” So we found the path, packed our lunches on us, and walked in a third of a mile or so to this huge, open beach. It was glorious! Some people took off their clothes and went in the water nude, and laid on the beach nude, and we ate.

It is amazing how things happen when you’re open to surprise, when you’re not planning everything. If we had reserved rooms at motels and lunches at restaurants along the way, we would never have run into amazing adventures like that.

Once I went into a surfing store and got all these stickers inspired by a woman we had seen in jail who wore a gold star. As we traveled along the ocean, we definitely got into another reality. In this reality we walked, we were together, we sang, and it was chem-free because I had just quit drinking and they were supporting me. By the time we got to Palm Beach we wore a lot of pretty stickers! You could wear an orchid on one cheek and a dolphin on the other! Some kid along the route looked at us and said, “There’s the sticker people!”

Gravitas

It’s not that there was no gravitas. We’d talk about peace, disarmament, liberation for women, and civil rights, and we’d talk about access to good food, and saving the Earth. Some people kept to that task nicely, and in every town we would call the newspaper and usually get an article. A lot of times, somebody would be interviewed on TV or the radio.

When we got to Palm Beach though, they didn’t want to let us walk through. We were too strange and too progressive. Two police cars stopped us and were trying to reroute us when we heard their police radio. Headquarters was calling and said, “Sheriff said leave them alone. If you try to stop them, it will cause an international incident!” And so they let us walk on.

Getting to Key West by car or on foot requires crossing the “Seven Mile Bridge.” We decided we would carry some food so no one would become hypoglycemic or anything over the ocean. We had a circle to discuss the dangers, along with what to do if somebody had to pee. The bridge had only a narrow sidewalk, and if the cars got distracted there was nowhere else to go. One of us felt it was too dangerous, and she was going to block consensus. When it was my turn to speak, I said, “I really see that is the reality, that it’s dangerous, and you are not being an alarmist. You are caring about us to object to us walking across that bridge. But maybe there will be a little crack in that reality that will let us through,” and it disarmed her. We walked across that bridge!

Last miles

We didn’t have money backing the Peace Walk, but people gave us money and help along the way, including offering places to stay. We had our sleeping bags and our blow-up air mattresses, our clothes and our food. All we needed was a floor, though it was nice to have a stove, and a bathroom, too. Most of the time it was all right!

Around the thirty-fifth day of the walk, we were in the keys but a long way from Key West. The keys are narrow, and there aren’t many open spaces, so we only had one yard and the floor of an apartment lined up for the next few days’ lodging. The yard, it turned out, was full of dog poop, and we didn’t want to put our tents up there. Somebody offered us a baseball field, but that’s not a very good camp site. We decided to go back to a restaurant we’d passed and figured a solution would be clearer to us after we ate!

When we got back to this restaurant, it was closed, but one of us had a lot of chutzpah and banged on the door. The woman who owned the place let us in and said she’d serve us. The name of the place was the End of the World! So many people in the keys are quirky, and they kind of dug what we were doing. She danced on the table for us, and then she let us spend the night in her restaurant! Things like that kept happening.

There was a lot of worry about where we would go after that night, and we talked about it in circle. I had an idea — we needed a Girl Scout camp! My mother had been a Girl Scout camp director and I had been a Girl Scout, so I kind of knew the organization. I woke up the next day determined to find one, but it was a long haul. I would go to stores and ask, “Do you know if there is a Girl Scout camp around here?” At this point, one group was walking, and I was with the group doing support. There were no phone book listings, and the keys are just one town after another – often not knowing very much about each other. But we finally found a camp! The caretakers had a little house at the gate, and we described our group and our needs. They said “absolutely not!” Undeterred, I found and posed our request to the professionals who hired the caretakers, but they also said no. Finally, I called the regional Scout offices that did have the authority to give access. They said, “We would be honored to have you stay at the camp because we saw you coming through Miami, and it was very moving.”

The camp was a tropical paradise! It had water on three sides and screened porches overlooking the water. It offered tents on platforms and a two-story kitchen house with a fully equipped French kitchen. Somehow, we managed to talk the Scouts into letting us stay three nights there. We had campfire circles, sunsets to end all sunsets, stars — it was spectacular!

As the Peace Walk neared Key West, several working friends from Gainesville were driving or flying back and forth to join us on weekends. We were meticulous and rigorous about walking every inch of the way, so we would mark where we left off each day, go spend the night, then return to start again the next day. After the Scout camp we were spoiled. Then we heard about a place called Sea Camp, which was an ocean study program in the keys for high school age kids. We met with the founder, explained what we were doing, and she said, “You know, I was a school teacher in Chicago and I had a dream of starting a camp that could really be the ocean, where kids could go under the ocean, in the ocean, and really learn about it. I lived out my dream, so I want to help you live yours.” She let us stay three nights, so that took us right up to Key West and the end of the Peace Walk.

Our last actions included a beautiful slow walk at a naval station, and throwing and catching colored yarn across a thirty foot diameter circle of women until a beautiful web was woven — the web was always to us a symbol of connection, a world and its people living as one. Some of us wanted to stay longer. I wanted to hang out with Barbara Deming more. Some had cars and went back home. But every day had been a real adventure. It’s amazing how an idea can become a dream you get to live in. It seems like you are lifted off the Earth a little bit!

Acknowledgements

Audio clips were recorded by Rena Carney on the first days of the Peace Walk in December 1983.

Photos of the Savannah River blockade and the Peace Walk were provided by Abby Bogomolny, Kate Gallagher, Jane Roy, and Lynda Lou Simmons from their collections.

Sunday Night Service at the Bamburg County Jail after the Savannah River Nuclear Bomb Plant Blockade

~ by Corky Culver

Was this heaven, these bars painted glossy gray,

these hard floors where we circled and sat on our

cracked plastic pillows stuffed

with about seven cups of hay, were these

the comfy clouds for angel seats?

They were, they were, sisters,

our visions were so clear and powerful,

the spiders and flies came to sit

on the webs we wove of yarn.

And was this a heavenly place to dry out

after years of drinking,

these sixteen days of uninterrupted company

of radical feminists,

sixteen days of dream sharing, circles of song,

global politics, sixteen days when

time and space gave us their blessings,

and stayed out of our way.

If I had to be shaking and quaking with the toxins taking

their leave of me, a hundred hugs a day

was more than an adequate replacement

for a jug of wine.

We were shaping a focus too sharp to shake

we were entering another consciousness

that would change the rest of our lives.

So . . . when the preacher came on Sunday night,

we thought perhaps he had come to ask for an herbal cure,

or a few words to the wise,

but no, he had not come to applaud our moral stand against

the Savannah River nuclear bomb plant where worker

were dying and nearby waters were steaming and birds

were disappearing.

No. He had come set upon our conversion from

homosexuality and purported communism.

Goddess, help us, we looked downstairs,

and they were setting up rows of chairs in the hall

to hold us in orderly files while we

endured our conversion.

No, thanks, we’ll stay up here behind these bars;

you’re not going to sink us on that submarine.

We declined his invitation

to the Sunday night missionary devotions

for the criminal element.

I could have told him, sir,

we are anarchists, we like our spirituality

in circles, where we’re all equal and we can all

preach at each other.

(I could have told him, but I didn’t bother.)

We stayed upstairs on the women’s floor, but

this preacher was not to be escaped so easily;

he had set up the service in the hall cause he wanted his voice

to step up the stairs, go through the bars, and enter our resistant ears

whether we wanted to hear or not.

So there he was,

firing salvos of salvation, rockets of religion,

up into our radical feminist and mostly lesbian heaven.

“Lord, save this Country from Perversion and Peace(niks).”

“Lordess,” we prayed in return,

“Save us from this man’s salvation.”

We didn’t want a confrontation, so

we just set up a non-violent force field,

whisper-singing our own songs,

to keep our heads on our own business,

our goddess songs, our anti-war songs,

our organizing songs (one right from his bible).

“And every one neath her vine and fig tree,

Shall live in peace and unafraid . . .

And into ploughshares turn their swords,

nations shall make war no more.”

When their service was over

(will any of our services ever be over?)

when the preacher bible-thumped his way on out,

and the male prisoners went back to their cells,

our own rituals erupted.

A day of peace need not be silent;

rejoice sisters, this Sunday night.

Paper cups became bongos,

the slats of a broken chair

become claves, wood blocks;

the backs of spoons clacked against each other,

and metal forks turned the cell bars

into a marimba.

Then boom, I realize, I’m trying to play music without booze.

It was different somehow from singing we are gentle, angry women

when the sheriff’s squad was twisting our thumbs

to pull our hands apart. Quitting drinking in order

to join the blockade and do civil disobedience was one thing

(I was ready to be serious and sober) but

to do music? to party?

Does anyone see the panic behind my smile?

Goddess, higher power, help this agnostic now.

I am screaming to myself,

I need cushioning for music,

my joints will pop apart, my skin will peel off.

Music is played by alcohol; it doesn’t come by itself.

I need to ride on alcohol’s wide back.

I can’t go on my own.

I look at my friends, at Blue and Quinn, twelve steppers for ten years,

at Lynda Lou and Judy who will quit drinking in solidarity with me,

at Kate swinging on the bars like Elvis in Jailhouse Rock.

I know I’m not on my own.

Our music picks me up and swings me around in its comforting arms.

I’m singing with them-bebop, scat.

My drinking cup is tuned over now

and I’m tapping and drumming on it

for a new dance.

It’s easy, over easy, it’s dry, no fry,

put your wings in your pocket and fly on by.

When the witches slap their britches

beating twelve to the bar,

we’re getting mighty high,

and we’re going mighty far.

I go to my bunk and listen to the last round,

salt exhilaration coming out of my pores and eyes–

ecstasy, x chromosome, ex-static, and SOBER!

The trustee comes upstairs and says,

Y’all better quiet down now,

and if you don’t mind my saying,

now I see why they call it,

the communist . . .party.”

I could have told him, “Sir, we are

radical, utopian, fallopian,

lesbian, Jewish, Christian.

We are anti-racist, anti-nuclear, goddess worshipping

separatists and non-separatists. We are

feminists, mothers, artists.”

I could have told him, but I didn’t bother.

NOTE: A previous version of this poem appeared in Older Queer Voices: the Intimacy of Survival, an on-line anthology edited by Sandra Lambert in 2017: https://olderqueervoices.com/