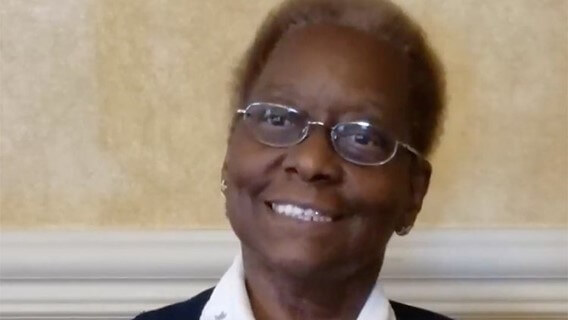

Carolyn Mobley-Bowie: Spiritual Warrior-Singer

Interviewed by Lorraine Fontana by phone on December 2, 2015

“Black people are my people, gay folk are my people, and church people are my people.”

Lorraine Fontana: Carolyn, please start with your family background. Where you were born? Who were your parents and siblings? Also, talk about growing up.

Carolyn Mobley-Bowie: I usually use the name Mobley, and my older brother goes by “Mobeley.” We answer to each of them and both of them. Carolyn Janette Mobley is how I was labeled when I was born in a little town called Sanford, in Florida. And I stayed in the South, or some portion of the South, pretty much all of my life so far. Now living as far “north” as I have ever lived, in Richmond, Virginia; yet it’s south of the Mason-Dixon line, they tell me. They consider this the South. In fact, I have learned the whole of the confederacy was here.

LF: Virginia is very much the South.

CMB: Yes, Virginia. I never thought of it that way, yet it is. I’ve been in the South my whole life. I’m from Sanford, Florida, and I grew up in a household with two parents until the age of ten. When I was ten years old, my father died at home of a war injury. He had been, I think, in the Korean war. I always thought it was World War II. My sister told me that he fought in the Korean war, lost a leg, and it never completely healed.

I was baptized at the age of ten in a Baptist church, First Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church in Sanford, Florida. I remember being in a church all my life, too. I grew up in there even before joining the church at age ten. I had been going to Sunday school, and my granddaddy was a Baptist preacher.

Biographical Note

Reverend Carolyn Mobley-Bowie, born in Sanford, Florida, in 1948, earned her religious education degree in 1971. Next, she did missionary work in the Commonwealth of the Bahamas. She took a position as youth director and minister of education in Orlando, Florida.

Rev. Carolyn Mobley-Bowie went to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1973, to attend seminary, which offered a master’s degree attainable in two to three years. During her days at seminary in Atlanta, she explored the gay lifestyle outside the classroom. After graduation in 1976, she became involved as a lay person with the MCC, the Metropolitan Community Church, which ministers to a mainly gay congregation.

The family had a story about me as an infant sitting in my granddaddy’s lap in the little, old country church called Stonehill Baptist in the same county as Sanford. Sanford is the county seat. In this little town, Stonehill, he’s getting so excited in church, that he stood up and forgot I was in his lap. I fell to the floor, and it broke my collarbone. My dad was a medic in the army, and he wrapped me up well. It was a Sunday, and of course, there were no doctors open in this little town. When they did find one, the doctor said, “Well, there’s nothing more I can do. This is a great bandage. We’ll just wait for it to heal.” [That is normal for collarbone injuries.] Thankfully, I’ve got two collarbones working well.

I finished high school right there in Sanford, as well. I was aware of being a lesbian, really, by the time I got to high school. And when I was a junior or senior in high school, you know, the pressure was to date a boy or do something. I “courted” this guy who used to come by my house and visit. His mom and my mom were good friends. They would worry about those nights that we were “dating.” You know, we never went out on a date per se. We just sat around the TV, kissing and petting. I was through with that by the time I graduated high school and went to college. Because I was always, even in high school, falling in love with girls, writing little notes, love letters, and journals, keeping that big secret.

I used to tell my mother all the time, or anybody else who would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, “I’m going to marry [woman’s name] when I grow up. She’s going to be my wife.” That was my babysitter at the time. And this is when I was like three, four, five years old talking. By the time I got to twenty-three, my mother told me to stop saying that. She’d say, “You’re not going marry no [woman’s name]. You’re going to marry a man, and nobody else.” I stopped saying it, but I didn’t stop feeling it. I still have a warm place in my heart for that woman, even as an adult. I think that I came out to her later, too; and anyway, she’s beautiful.

Studying Religious Education

I went to a predominantly white, coed college, Hardin-Simmons, in Abilene, Texas. I was tempted to go to Spelman [the private, historically Black, women’s college in Atlanta, Georgia] because that would have been in line. My brother had already gone to Morehouse [the male counterpart to Spelman in Atlanta]. We didn’t have any women in our family who had gone to Spelman, and I thought, “I’ll be the first.”

But then, I thought, “Oh, my God, all those women all the time…” I would never do any studying. I’d just be messing around with girls all the time, and I’d flunk out of school. I thought, “I’d better give myself a chance. I’m going to a white school, in a far-off place –Abilene Texas – and I won’t be bothered by being a lesbian anymore.” Surprise! It goes with you. I was falling in love with girls in my freshman class, and with seniors, and women who were upperclassmen. One in particular was my “big sister.” I am still fond of her. I’ve come out to her now, too.

I went to college to do a degree in religious education. I knew that I wanted to be working in the church all my life, partly, I’m sure, because that’s just my culture. I never felt called to be a preacher. Women weren’t supposed to be preachers. I wasn’t trying to “buck the system.” I just wanted to serve God. I loved God with all my heart, and I wanted to serve in the church, I figured, as a missionary or teacher or something. I got out of college in 1971.

By this time, I had fallen in love with enough girls to know I was a lesbian. About that time, I was REALLY interested in this woman who was ten years my senior. She was of European descent, and she was a missionary in the Bahamas. She was around black people all the time. She loved my people; she loved me. I met her at a conference in my senior year in college. Upon my graduation, I went to visit her down in the Bahamas, which was awesome. And when I got on the plane to come back, I thought I would die from longing to be with her. I considered moving down there, and forgetting everything else. But I already had a job set up in Orlando. I had to come back.

Exploring Gay Life in Orlando, Florida

I worked at Shiloh Baptist Church in Orlando, Florida, as the youth director and minister of education. I was doing my dream: working in a Black church, not preaching, but working as education director, and working as church secretary. That came with the job, kind of a dual deal.

Yet I could not escape my lesbianism. It was right there with me in church and in the office, and somehow… There was a woman hired after I was. She was taking on the secretarial position, and I could do more with the educational piece. She was a lesbian who introduced me to a young woman, and I had an extended affair with that young woman. I thought, “Wow, first time.”

However, let me back up a little, here. The woman I went to see in the Bahamas really is the woman who brought me out. She came to visit me when she was leaving the mission. She was on the way to North Carolina, and she stayed with me in Tulsa. We made love right there. That was the first time. I thought, “Oh, OK, this is what I’ve been waiting for.” Even though I know that I can’t go with her, I wanted to follow her. I told myself, “Her life is more religious than mine, she’s ten years older, she’s white, I’m Black: it’s not going to work. I’m going to stay here and see what’s happening where I am.”

I did fall in love with an outside woman, in church and out of church. The woman that my friend at Shiloh Baptist had introduced me to happened to be a hooker, of all things. As we dated and she came home with me, we found out that her momma and my Aunt Jean, who lived in Jacksonville, Florida, knew each other, and they were best friends. This woman knew my aunt, and called her Miss Collins. “Hey, Miss Collins,” and my aunt turned around and called my friend by her real name.

Then, I got the whole story that her mom and my Aunt Jean were bosom buddies, drinking buddies, hanging out in the projects, living, you know, as neighbors, and all that. And this woman that I was with used to be in and out of my auntie’s house all the time as a kid in Jacksonville. It blew my mind. My Auntie Jean said to her, “Your mom know where you’re at? You’d better call….” I took this girlfriend to visit her mother. She hadn’t seen her in ten years or more. My girlfriend turned out to be a drug addict, unfortunately. At the time, I knew she was a prostitute, but I didn’t know about the drug addiction. She ended up getting taken away by her pimp, and I didn’t see her anymore. They moved out of the city. She told me not to try to reach her. That was a piece of my life that was done.

Brokenhearted and looking for another way to be comforted, I picked up another relationship with a distant cousin, who had been writing to me. We finally connected. That kind of began my coming out experience of “serial monogamy.” I was always faithful to one woman, and one at a time. And later on, I actually was in a long-term relationship during which I had two or three affairs, a real difference. I was kind of growing up and coming of age in Central Florida, first in Sanford and then in Orlando, for work and really coming out.

That’s when I came out to my mom. I told her the real deal. “Don’t ask me about getting married. I’m not marrying no man. I’m not marrying no man, ever. Please, don’t ask me about that anymore. If you want to know the real truth about my life, I’ll tell you.” I did tell her about all my girlfriends.

Moving to Atlanta, Georgia, for Seminary

In 1973, I was ready to leave Orlando to go to seminary and move to Atlanta, Georgia, for the first time. I had been seeing a woman there who, unfortunately, was married to a man. She told me that they were getting divorced, and that he didn’t live with her there. It turned out that he was a football player for the Chicago Bears. He was still married to her, and he took that seriously, in terms of his not wanting anybody else to be with her. Since that backfired on me, I got out of that, and I moved to Atlanta.

In Atlanta, I kept coming out. I was very excited to meet all the gay people in my new classes. I became tight friends with one young man, who became like a brother. People thought that we were dating, and we let them think that. He was gay. He took me to my first gay bar, and he told me about gay life. He later dated a gay male cousin of mine, or at least, he had an affair with him. I wouldn’t say “dated.” We were good buddies. His name was Gerald, and I credit him with a lot of my growing up as a lesbian in Atlanta in those early years of 1973,’74, and ’75.

Leaving the Baptist Missionary Work

I graduated seminary in 1976. [The seminary was the Baptist component of the Interdenominational Theological Center (ITC).] By that time, I was involved in the MCC [Metropolitan Community Church], as a layperson, while also working for the Southern Baptist Convention. That was my first job after graduating seminary. In May 1976, I started working for the Southern Baptist Convention as a career missionary. I did that for five years before they decided that they wanted to ask me if I was gay or not. I refused to answer. They told me, “If you can’t tell us you’re not a lesbian, then you have to resign.” I said, “I’m not going to tell you anything. But if you want me to resign, I’ll be glad to do that as soon as I figure out who’s going to replace me, to train my own replacement.” And I did that.

They paid me a full salary for six months after I left the job. They had no reason to fire me other than their suspicion that I was gay, and I know that they knew they were wrong. I told them: “I’d rather be single than be part of a church that thinks of me as a homosexual or a whore, and nothing else.” And I said, “I’m just not going to live under that kind of scrutiny, and I am not going to lie about who I am.” I didn’t lie, yet I didn’t tell them the whole truth.

I left there, immediately joining the MCC. I had been attending the MCC anyway. In 1981, I became a formal member of the MCC in Atlanta, and continued to expose myself to the gay community. I went to my first gay pride [event] in 1981. That summer, I figured that if I’m going to be out, I’m going to be out-out. They had basically put me out of the Baptist church, and I told myself, “That’s fine. I don’t need to work in the church. I can work in the world. I’m a human being with two degrees. I’m sure I’m smart enough to do some kind of a job.”

I became a courier. That’s a no-brainer job. A friend of mine who was also Baptist had gotten kicked out of his professorship in South Carolina, at a big Baptist university. He was driving for a delivery company, and he got me a job there. I thought, “Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, God.” I worked for that delivery company for a couple of years when one of the managers there broke off on his own to become an owner of a similar company. I got to be a driver, a foot carrier, and then I worked inside the office doing customer service work, which was great experience for me. I loved it, and they paid more than the church was paying me. I thought I’d stay there and do that.

Working in the Atlanta Lesbian and Gay Community

During those years when I was working as a courier, I became involved in the lesbian and gay community on a large scale. I sang with the Atlanta Feminist Women’s Chorus for ten years. I was one of their soloists. I was very active in that group, and in the coed, lesbian and gay chorus I sang with, Lambda Chorale. I was active in gay pride celebrations every year, of course. Toward the end of my time in Atlanta, maybe 1986 or ’87, I helped to start a group called the African American Lesbian and Gay Alliance [AALGA].

After I left the courier business, I was working at Charis [Charis Books & More, the feminist bookstore]. I was hoping at that time that they were going to make me and the other young woman a partner, along with the owners, Linda [Bryant] and her partner [Sherry Emory]. They decided against that, and both I and the young woman ended up leaving. We were hoping to work at something like that, and I was looking at getting money to put into it.

LF: I didn’t know about that story. Many of us lesbians worked at Charis at one point or another. I didn’t realize that you had wanted to become a partner in the ownership, and that’s interesting.

CMB: That’s what Linda had expressed when she had me and this other woman (I can see her face now, yet I can’t remember her name). We were both in training, as management trainees, that’s what they called it. And after we had worked a while, we would see if we wanted to buy in. They were working out what that would look like, and in the end, they decided against it. Mainly, I think Linda felt I could not fully commit to that because she knew about my religious background. I hadn’t shared with her that I was considering, you know, a church job at that time, too. I probably would have stayed there, and let Houston go. I knew Atlanta well. But I didn’t want to just stay there to work for a small amount of money when I could make a full-time salary somewhere.

In about 1981, AIDS became a big issue. I had to volunteer at the gay community center, where they trained me as their AIDS educator. I did AIDS 101 with a lot of people. I became a volunteer for the first time for people living with AIDS. They assigned me to a woman who was dying, a Black woman, at Grady Hospital. I only got to see her once, and to chat with her about her faith, God, and how much I loved her. I hope it made a difference. She died shortly after that in Forsyth, Georgia, the town where I was.

In Atlanta, at the MCC, I saw lots of people die of AIDS. I did several funerals as well as my clergy work. I was a deacon, which was enough to do a funeral or to preach, to do everything but baptize people. I did serve the Lord’s Supper. I guess I could have baptized somebody’s dead ass. I was very active as a lay-leader in the MCC from 1981 to 1990.

[When becoming a partner in Charis did not turn out], that’s when I decided to accept the job in Texas. I pulled out of there in May or June, 1990. Off to Houston.

After about eight or nine years of doing those different jobs, I had decided that I wanted to work in the church. I had been invited to a position at the Second Baptist MCC in the regional Fellowship in Houston, Texas. I went and I worked there from 1990 to 2005. In ’92, after being there just two years, they made me the grand marshal of the gay pride parade in Houston, which sounds incredible being so new there. I did lots of community things at the bars. In the early 1990s, I did a couple of memorial services at the bars for people when AIDS was still taking folks right and left. They finally started getting drugs that let people live much, much longer. I was as active in Houston as I had been in Atlanta.

Forming LGBT Organizations

LF: When you were back here in Atlanta for a little bit during the past twenty years, did you relate to the organization, Zami?

CMB: Yeah, I began to seek out Zami because it was most like the group called SISTERS that we had started in Houston. Zami, in Atlanta, was focused on African American lesbians. I sought them out, got to know a couple of the folks leading it, and attended maybe three or four of their functions during that time I was there. They did mostly things only twice a year or once a year. I went to those, and all of them were wonderful, their parties as well as the roundtable discussion they had about butch and femme, and about looking at racism, sexism, and all the “-isms.”

LF: The African American Lesbian Gay Alliance, AALGA. I was just thinking about lesbian groups, like Sisters, and I remembered AALGA.

CMB: After I was in Houston just a short time, the woman that I was partners with at the time (we were together 4-1/2 years) started a group called S.I.S.T.E.R.S., Sharing Inner Strength Through Encouragement and Realistic Support, all capital letters. [There is a group called Sisters in Atlanta, too, but Mobley-Bowie was not familiar with it.] We helped form an African American lesbian/gay support group, same idea, in Richmond, Virginia, too. We started that about 1993, I think. It was an amazing group.

Back in Atlanta, I was very active in AALGA (African American Lesbian and Gay Alliance) along with a gay man, Duncan Teague. The first president was a gay man who later died of AIDS. We had a big memorial for him at the MCC with lots of folks from all over the city. He had worked at Morehouse College in one of the offices, and he was a tremendous human being.

LF: What was his name?

CMB: Marcus Walker. We did the Marcus Walker award. I got the first one, from AALGA, in his memory. We did “extra-spiritual” services. I didn’t want to call it “ecumenical” because that’s what [another group] called its gathering. I came up with the term “extra-spiritual” because we worked in different religions, including people who weren’t identified in a Christian religion. We did that through AALGA. It was in the early or mid-1980s that we started AALGA, and it was still going after I left Atlanta.

On Womanism and Feminism

LF: Did you identify as a feminist or womanist ? How did you relate to the mixed groups? Were you in any all-lesbian groups? If so, how was that for you in relation to working with men and other women?

CMB: Coming out, I was fully aware of who I was by the time I moved to Atlanta. While I was in seminary, I continued to come out. After graduation in 1976, I began to really check out organizations. Carole Etzler [now Carole Eagleheart] was a friend of mine who was a feminist songwriter. She worked at the Presbyterian Center at the time, and I’m on one of her albums, Womanriver Flowing On (1977). She was the first feminist that I really remember meeting. While I was still in seminary, I also got involved in a feminist house church called “Becoming.”

My last year and the first two years after graduating seminary, I continued to meet with those women. They were a largely Catholic group, some Presbyterians, obviously, as Carole was Presbyterian. The woman who has been for years now the chaplain at the woman’s prison outside of Atlanta was also part of this house church. She is on one of Carole’s albums with me. I had been running in feminist circles in the late 1970s and into the 1980s.

Of course, I was aware of ALFA [the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance]. I went to the ALFA house from time to time to look at their books, early on, and to get reading materials while I was still in seminary. Of course, I met two or three young African American lesbians who were at either at Spelman or Clark College, and they used the ALFA house a lot as “coming out” ground for learning stuff, reading materials, meeting other women, that sort of thing. ALFA was feminist, and the feminist house church was, too. I became aware of womanism, the womanist movement really, sometime later while I was still in Atlanta.

I didn’t fully identify as a womanist because feminism seemed broader to me. Plus, I kind of liked the idea of all-woman space that doesn’t include men. But the womanist perspective is that we can’t move forward without the men. Because we’re Black, that takes precedence over being gay. I never have figured out if that’s true for me or not. I think it is. Yet being gay is such a core part of who I am. It’s a part of me that’s not negotiable. You know, I didn’t choose it, and I can’t give it away. It’s the same with being Black. I didn’t choose that either, and I certainly can’t give that away. Womanism and feminism began to merge, or kind of blend with me, I guess, while I was still in Atlanta. It separated out more as I moved to Houston, I think.

I was more a womanist there [in Houston] because I ran into Black women. A group called Afro Fem Centric was already started before we started SISTERS. Afro Fem Centric was kind of fading out, and they weren’t getting very much attendance. We started SISTERS, and that drew a bigger crowd at first. You know, every organization waxes and wanes, and we had our ups and downs, too. Feminism for me, as a part of my identity, emerged because I am woman identified. As a lesbian in high school, even when you all weren’t using it [the word “lesbian”], I knew what it was. I had looked it up in the dictionary, and I thought, “Hmm, OK, that’s me!” Moving on through life, I continued to relate to feminists, even though, the more I got into African American history . . . [the more she saw the historically racist component of feminism, described next].

I have a video that talks about the feminist movement. It documents a period when the suffragists were a big thing, trying to get the vote for women. That vote happened at the expense of Black people, in general, because the women of the main feminist movement would not include Black women. They thought it would hurt their cause with the white male legislators. If you’re going to give all women the vote, not just white women, you know, that whole slavery thing confused the issue. They couldn’t separate it out. Except they did, to say, “Well, get the women’s vote, THEN we’ll help slaves to get free, and help, you know, Black men and Black women to get to vote.” It was a long time coming, and it did happen. If I could rewrite history, I would have women standing together so strong that they would embrace overcoming racism, simultaneous to overcoming patriarchy. Anyway, that’s how I kind of developed on that.

Racism in the LGBT Community

The more I got in touch with the inconsistencies in the Black community, the more I leaned toward womanism and away from feminism. However, I could never exclude feminism as a part of my core identity. I remember in Atlanta there was a period of time when the gay bars were double carding Black gay men, as in requiring more ID. They were giving them a hassle, trying to keep them out. Eventually they had to let in all gay people, regardless of color or gender identity, or any of that. Now we know. The gay community center didn’t speak up against the racism within the lesbian and gay community. I never let that be a stopping factor for me, and yet, it certainly was a hindrance. I think I was one of those African Americans that became the exception, and you can recognize that. It’s like, “We know Carolyn. We like her. We don’t like the rest of you Black People very much, you know, but she can come.” And I didn’t like that, being the only one. That was true in the MCC. I was the only one for a long, long time. Me and a guy name Darrell. He lived in Washington, DC, and every time I go there now, I stay with him. We were both in an MCC.

I didn’t know at the time that there’s this unspoken rule: people of European descent in America can have mixed groups as long as they are the predominant group. They can handle 5% or 10% or 12% of the room, or the organization, or church, being Black. Just don’t let it become 15%, 20%, 25%, or 50%, or they are out of there. You know, it’s just overwhelming to most people of European descent. They can handle a little, but not a lot of integration. The whole idea of integration as it was happening in the schools [was dealt with by] keeping schools segregated by starting private schools. That’s kind of where our culture is. I’m sorry to say that I think that a lot of that still exists. People that don’t want to have Black people involved in their lives can escape by starting something new and private, somewhere else.

The good news, in my mind, is that as more people relate to each other intimately, whether in marriage or as sex partners, some of that is becoming overcome. So that if I am with a European-descent woman and she really loves me, she’s going to have to stand with me, with Black people, and get comfortable with being the only white person in the room sometimes. I think this is happening some. I think that’s happening all the more with Barack Obama as a mixed race Black man. He identifies as Black, and you know, some people think he’s half white, and he is. He’s still himself.

That’s a whole surprising thing to me. In this country, if you got any of what they call Black blood in you, that makes you Black. If you’re 2/5 African American, I don’t care how white your skin is, you’re still African American. That says something about how deeply rooted racism is in this country, and how it cannot really be overcome overnight. I think that the only thing that will really undermine racism is when people understand there’s one race: human. We come in all shapes, all textures of hair, and there’s one race, the human race. And it will be a better world when that day comes. But in the meantime…

LF: Would you say that feminism and womanism are nearly the same?

CMB: Feminism and womanism are meeting more, I think. I have been to a number of conferences and such, where womanists and feminists are both on the stage and speaking about their passions and their call for justice. I think that feminists and gay people in general have learned that the best way to move our agenda forward is in coalition with others who have a similar agenda: justice.

Women want justice, gay people want justice, Black folk want justice. All of our lives do add up, but when one part of life is getting attacked, we have to raise that up. Black lives are getting attacked. Literally, physically. And killed. We have to say: Black lives matter [as much as] all lives matter. We need to pay attention to who is being hurt the most. That’s kind of where I am with that.

I enjoy women’s company, period. All colors, all races and colors. I learned that I could fall in love with white women, with Asian women. There was a Hawaiian woman in our freshman class, and I was crazy about her. Pretty as she could be. She was not a lesbian, and I didn’t ever come on to her. I was good enough friends with her that I could admire her from afar. When I moved back to Atlanta, and I first started coming out after college, my first, long-term relationships were with women of European descent. A woman named Julia. We started going to the MCC together. And then later a woman who still lives in Atlanta, and who is not involved in the MCC very much anymore, kind of a non-church person. She’s a beautiful person indeed. A strong heart of faith; just not into religion in terms of the practice thereof; yet she has her spirituality. It’s very, very deep, and very personal.

When I got to Houston and was made grand marshal at the lesbian and gay pride parade, I got interviewed about it. At the tail end of that interview, I talked about my people. They asked me, “Who are your people?” I said, “Well, lately, all people. I have three groups that I identify with as my people. First of all, Black people are my people. You know, that’s how I grew up. That was the first way that I understood myself in the world. I was a Black person. So, Black folk are my people.” And I said, “Gay folk are my people. All gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people are my people because I also identify as lesbian.” And I said, “Church people are my people. I love the folk outside the church, too.” I’ve simply chosen to train and live and work through the church. And so, those are my people. Black folk, gay folk, and Christian folk. Even the bad ones among them. I know that Christianity has some serious problems, particularly with the right-wing side. To me, there’s enough pull on the left side to bring us closer to the center. That’s where I am in the MCC.

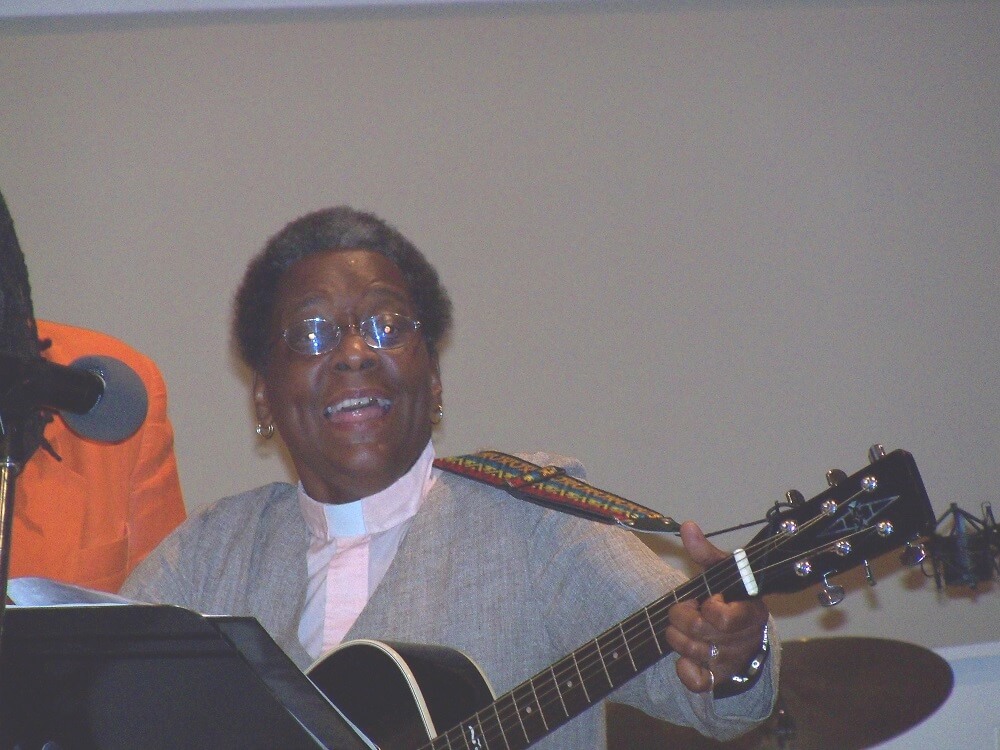

Singing All Her Life

LF: I want you to talk some about your musical gifts and talents and how that started. You’re a singer and you play the guitar, and maybe other instruments that I don’t know about. And you write. Tell me how all of that started, and how that fit in with the various parts of your life.

CMB: I’ve been singing since I was five years old, probably sooner than that, just singing along with the radio and harmonizing. I have a natural ear for harmony. Growing up in Sanford, I sang in the church choir. As a kid, I got to sing with the gospel group because I was good. Even though I was too young to be in it, they let me sing in it anyway. Church music, church choir, high school choir, and college choirs, I was always a part of that. So, everywhere I went, I sang in whatever group was available.

When I went to Hardin Simmons as a freshman, two other freshmen girls and myself started a little group called the Sojourners. We sang really well together. Two of them played the guitar, one also on the tambourine. We sang folk songs and religious songs mostly. We traveled in Texas, central Texas and west Texas. We impressed enough people that when the Baptist World Alliance came around in 1970, [we were invited to sing there.] (The Southern Baptist Convention was having the Baptist World Alliance in Japan the same time as the World’s Fair was in Osaka). We flew to Tokyo, and we sang at these little, itty-bitty, Southern Baptist Japanese churches all week long. We spent the weekend singing. Saturday afternoon we sang at the American Pavilion at the World’s Fair. We got to meet lots of people. Not a lot of English was spoken, so when you heard somebody speaking English, you gravitated toward them. We met people who were speaking all kinds of languages, and it was wonderful. We learned a little Japanese, and we learned to sing a couple of religious songs in Japanese. Really, you can identify singing with everything I’ve done.

I was on staff in Houston for fifteen years as associate minister of the Resurrection MCC Church. I was their first Black woman on staff. I sang with the regular choir from time to time, and also started a group called the Gospel Ensemble, which is now racially mixed, featuring Black and Black gospel music. They don’t sing anthems and they only sing Black gospel music. The people who are in it love that. The church in Houston also has a sanctuary choir that does a variety of music. They have a little southern quartet, and a handbell choir, all kinds of musical stuff. The Gospel Ensemble is something that I started, and that survived even after I left.

I was delighted when women’s chorus in Atlanta got started. Linda Vaughn, the founding director, and I were good friends, and we still remain friends. I call her once in a while. Of course, she retired after about ten or twelve years. I came back for that 10th year reunion because I had just moved to Atlanta in 1990 or ’91. I came back and sang for their reunion concert; we did a special number dedicated to Linda Vaughn. [Vaughn directed the Atlanta Feminist Women’s Chorus (1981-2009) until 1993.]

That’s when I got into women’s music. Women’s music is something that happened to me in Atlanta, during the time I was an active feminist. I loved Olivia Records, anything and everything that they produced. All that’s left for me to do now is go on an Olivia cruise. I have not done that yet, and I still want to. I went to the concerts, and I sang at women’s music festivals, the one in North Georgia, later on, and at the one in Texas. I never got to go to the one that one that’s held in August every year, up in, what state is that? Indiana or Michigan? [There was a women’s music festival in each of those states.]

LF: Yes, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival.

CMB: I’ve never gotten to do that one so far. That may still be in my future, too.

LF: The last one was held this year.

CMB: Oh, really? That was the last one?

LF: Yes, they decided to end it.

CMB: Wow. Well, I missed that era. I was aware of it the whole time, mindful of it, hearing music of it, and thinking about music from it. Of course, singing with Carole Etzler, who’s a feminist songwriter, musician, and artist who got me into a lot of feminist music and women’s music. [Etzler later changed her surname to Eagleheart. She became a Unitarian Universalist minister.]

When I met my current partner, she had never heard of women’s music. She has always been a Motown girl. She grew up in Saginaw, Michigan, and she went to Detroit all the time. She actually worked at radio stations that were Black stations: Motown, Rhythm and Blues, all that stuff. She had never heard of women’s music. On our first date, I brought her home, and we sat on a beach towel or something like that, and we listened to women’s music.

LF: What did she think of it?

CMB: She liked it. She mentioned people like Linda Tillery, you know, that she was impressed by. I was crazy about Cris Williamson, of course, and others, and she liked that music, too. It was good, and she liked the words. The style was different for her. It didn’t have enough rhythm and beat for the most part. She liked a little more upbeat.

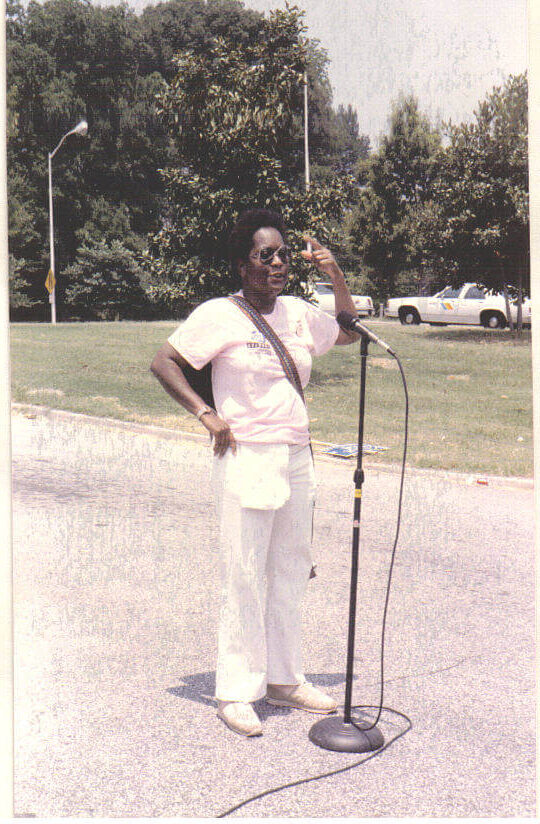

LF: Yes, a lot of it is more like folk music. The one picture I have of you that I remember is you playing your guitar and singing, before the lesbian and gay pride parade, like at a rally.

CMB: Oh, yes! I will never forget. You’re right; I did that. I even had a chance to go to Boise, Idaho, for their first ever gay pride. And our friend who had moved from Atlanta to Boise, and then up to Oregon after that, made me promise I would come bring my guitar to lead them in singing, too, the way she had seen me do in Atlanta. I loved that. But the thing that stands out in my mind is the time in 1981 or ’82, when some Baptists used all that rhetoric about God, saying AIDS was God’s condemnation of gays. We had to stand up against that.

We did this silent protest, and it was huge. We met at the MARTA [Atlanta rapid transit system] station downtown nearest First Baptist Church. We walked from there to that church, and then circled the church. The whole city block, just people lined around facing the church. We didn’t say anything. We didn’t do anything. As soon as their church service was over, people leaving the church saw us. They knew our purpose. We had some signs: “God loves Gays,” “AIDS is not a punishment,” and “Gay people are not the only people with AIDS,” you know, all of that. We were singing the song, “We are Gay and Lesbian People”at the MARTA station that day. That’s the little theme song that I do sometimes at gay gatherings, that’s a Holly Near song. (Singing: “We are gay and lesbian people, and we are singing, singing for our lives….”)

I sang it in Boise, Idaho, for their first ever gay pride event. I sang a little bit at the pride function in Houston, on the gay pride parade float. When I was in Houston, the MCC always had a float, and sometimes, we had our choir. I remember singing in the last few years on the float with them. Of course, I rode in the car the year I was grand marshal. Other times, I walked with the MCC in those parades, or I was on their float singing with a small group.

Music has always been a part of everything I’ve done, from preaching, when I always sing, to leading rallies with my guitar, and singing community songs. That was much the way the civil rights movement was. We always sang at all of our civil rights gatherings. Of course, in the gay community we still sing “We Shall Overcome” from time to time. We are still overcoming, still in the process.

LF: Yes, still. In Atlanta, the lesbian and gay movement here always remained quite segregated. There haven’t been many positive, successful attempts to have multicultural, multiracial groups and organizations participating. When there was ALFA, and when you started AALGA, was there also a Black, lesbian and gay community, having things such as house parties and not-so-public organizations? Tell me what you knew about that.

CMB: A little bit. I didn’t know as much about the house parties as some others. I was aware of them mainly because of Black, gay male friends that I knew. And there were a couple of efforts in Atlanta, as I recall, for Black gay clubs. Women would come, but those clubs wouldn’t last very long. Because women, Black gay women, were the poorest among lesbian and gay people in terms of having extra money to spend on going out. That’s why those businesses and clubs didn’t last very long. They didn’t – couldn’t – attract big enough crowds to stay in business.

In terms of race and integration as it related to women’s organizations, and to lesbian and gay organizations, I think it’s very difficult. That they may remain segregated is proof positive that it’s very difficult to integrate them. My take on that is if we, as African American people, can bond together and build strong, Black, lesbian and gay organizations, then we have a voice in the larger lesbian and gay movement. It would make a pool of Black folk who are out and gay, or open to some extent, that predominantly white lesbian and gay organizations would have access to. Then there would be more than just one Black person at the event. You can invite the whole AALGA team to participate in gay pride events, for instance, and not merely one person here or there. You can invite the whole AALGA group to a play or function that ALFA, or SISTERS even, or Zami are giving. Zami is another group where you can find a group of Black women rather than just the leader or an individual person.

It’s hard to integrate because birds of a feather flock together. That’s real. Water does seek its own level. That’s real. People are more comfortable in segregated groups. Everybody, Black folk, too. There are some Black people who think integration was the worst thing that happened to our community. It tore us apart; it separated us; it splintered us. We no longer have strong, Black schools as we used to. Even when I was in elementary school, we were learning Black history. It was not being taught at the white schools. I don’t even know if they celebrated Black history day or week or month or anything. As we move into those larger circles, we had to bring Black history celebrations with us. That’s where other people began to get some information and learn that there was a whole vast array of writings and materials and movement that they had been blind to before.

Whites can live in a sanitary society if they want. I mean by that that they can easily avoid being around Black people. On the other hand, Black people cannot avoid white people as easily. We can cling to each other in smaller groups, but we still have to go into that bigger world to ride the bus, to get a job, to go to movies. I don’t know any black-owned movie theaters. Maybe there are. I just haven’t seen any. There should have been, back in the day, when we were relegated to only the balcony of movie houses, when we couldn’t go sit downstairs. I remember that in my hometown. There were even places you couldn’t get into, period, not even in the balcony. You couldn’t get in if you were Black. That’s exactly the way segregation works. We’re much better now in those public accommodation things, public venue places. But the places where we still have a choice, like church and private clubs, that’s where segregation will abound.

MCC and Racial Diversity

LF: The MCC over the years, starting as many LGBT things as they did back then, was predominantly white, almost all white. Has that changed over the years in terms of the ability to be more multicultural and interracial?

CMB: I think at the top, the MCC has remained committed to that, has modeled it. It has filtered down to some of our churches. I can name the ones that have any kind of decent African American presence: the one here in Richmond (Virginia) is about one-third Black. Resurrection MCC in Houston (Texas), is about one-fourth if not one-third Black. The MCC in Washington, D.C., is almost 50/50, and there are more Blacks there than whites in terms of who attends on Sunday mornings. It’s a very, very mixed congregation with a strong, Afrocentric presence with its music. Gospel music is the main music, not a separate choir that does something other than gospel, like at Resurrection MCC. There are a few others.

The Los Angeles (California) MCC, the MCC L.A., has a sizeable Black presence. Yet after Troy left, and after Matthew Wilson left, the new pastor that came didn’t draw as many Black people. [Troy Perry founded the MCC, and the first MCC church was in California.] Some didn’t like the new minister, didn’t feel like he was leading the church in the right direction. He was from Europe, a British guy newly in America, pastoring an American church. Because he was white and younger, he attracted younger, gay white men much more than he would women of any color, and certainly people of color in general. They maintain a strong Hispanic movement within the MCC L.A. They meet at different hours, they have an all-Spanish language service, and they are part of the bigger church when it comes to congregational meetings, to large, church-wide fellowship things, yet they worship separately and have their own pastor.

Even the church in Las Vegas [Nevada] has maybe a congregation that’s one-fifth African American. Wanda Floyd, a Black woman from North Carolina, is their interim pastor. She has brought more Black people into it. The MCC Las Vegas had a strong Hispanic congregation that has since broken away to start its own, unique ministry.

LF: Getting back to the South and to Atlanta, tell us what is your story and experience with MCC Atlanta. Now, there are more than one MCC in the Atlanta area. There weren’t very many African American folks in that church, at least when I knew it, in the 1970s.

CMB: Right. Well, I was, as I said, the only one for a long time was there on North Highland Avenue. As they grew, they moved to the place on Colby Circle, right off the Interstate Highway I-85, and into whatever that neighborhood is.

LF: The neighborhood is North Druid Hills.

CMB: North Druid Hills, right. In that location, they grew their Black constituency a lot. There was at least one-fourth, if not more, of that congregation that was African American by the time that I left there about 22 years ago. They did not reflect that in the leadership because the pastor was not, let’s say, it [inclusion of African Americans] wasn’t on his radar or it wasn’t his primary concern.

Every MCC that has broadened its African American constituency has had to make a really deliberate effort on the part of the leader. Like the guy at Resurrection MCC in Houston [Texas]. He hired me knowing that a bunch of folk weren’t happy not having a Black person on staff, paid full time. It grew, and kept on growing African American participation and involvement to the point that now, they have, have had, a racially mixed staff. Ever since then, Black people are being paid by the church to do whatever they do. They recently hired a young woman as associate pastor, who came through Resurrection MCC when I was there. She is a clergy person now and has been hired by that church. Yes, the MCC has grown in terms of its inclusive nature because they have been intentional from the top, where it counts.

My heart’s desire, from 1981, when I left the Southern Baptist Church, was that the MCC Atlanta would grow to the place where they could afford two pastors, and that they would have me as one of them, as an associate. I wouldn’t really want to be a senior pastor anyway. That’s not my gifts or calling. But I could help as an associate pastor or a staff pastor, focused on outreach and community connection. That’s where I’m strongest.

I’m not that good of a preacher. I’m OK. I mean, I can do it, and I’ve managed to do it. It’s not really a passion of mine, and I don’t really love to preach. I love to sing.

LF: That’s probably true in any place, any institution.

CMB: Right, of course.

LF: Why is it that you would stay with the MCC rather then get into, like, Unity Fellowship, or some all-Black or majority Black congregation?

CMB: Good question, good question, yes. Everything is a tradeoff. My feminism is too strong to be part of Unity Fellowship because they are so sexist that it’s pathetic.

LF: Oh, I didn’t know that.

CMB: Black men. Black men are running everything.

LF: It’s not like that here in Atlanta now. Unity’s minister is Marissa Penderman.

CMB: Yeah, all right, they’re growing in that area. When I was coming through, and when I had the opportunity to switch, it was not worth switching for me. I didn’t want to deal with the sexism of Black men. They were not speaking of God except for the story of Eden. Some of them still love the St. James version. I was not interested. I’m still not.

I would do a Unity Church that was racially mixed, or the Black men from Bishop Saunders’ church [the United Church of Jesus Christ (Apostolic)]. Bishop Saunders, her Pentecostal movement is predominantly Black, and she’s open to others as well. There are some white Pentecostal groups that are affiliated with her. For the most part, she is nonsexist, a feminist, and a womanist in her preaching, and she’s mindful of inclusive language. I’m attracted to all of that. But a lot of people in the pew still are into the St. James Bible. They can’t see God as anything other than that. I could not make the theological leap.

The MCC is where I am theologically about inclusion, too. I stay with the MCC because I believe in the dream. The dream is multicultural, multiracial, everybody on the same, level playing field. It’s not there, but we’re moving in that direction. We have from day one. That’s been the intention, that’s been the goal. And it’s never wavered as to what we want to see for all of our churches. If we get discouraged because the church is not as blended as we want racially, and if we leave, it’ll never happen. That’s why I stayed to help it out. I did see it happen to some extent in Houston and in Atlanta. Of course, it was already happening in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles before I came along.

There are many, many more MCCs where they have a handful of one, two, three Black people. You know, you can count them on the fingers of one hand. For the longest time, the MCC of Lubbock, Texas had one Black person. Her name was Mary Anne. She came to the People of African Descent conference, sponsored by the MCC. That’s the other thing: the fellowship. You have the MCC Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches. They have always been clear about this on the denominational level, about doing things that meet the needs of the folks who are attending.

The MCC did not have very many Black pastors. Black folk who are attending put together a list of things that we needed to see: Black elders, Blacks on the staff of the fellowship, Blacks on the administrative level. We also need to have more Black preachers ordained. There’s a stumbling block in ordaining cause you’re required to get a seminary degree. Lots of Black folk from the traditions we come from don’t go to seminaries. If God calls you, whether you go to school or not, it’s your choice. But God is still going to use you. You can pastor and preach without a degree.

Now, even more Black churches are moving toward degreed pastors, and that’s a blessing. It is still a long, arduous journey: five years to be ordained. That was a stumbling block that kept black people from being ordained. That’s true in other denominations, too. Now, it takes about five years in the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches, and it’s about five years for the Unity seminary. It may take a while to get the experience and the training under your belt. I’d say it’s worth it [for me] because it was the best place to plant myself, to grow, and to help create what I wanted to see exist in the world.

LF: Thank you for that. Do you have other things to say that are relevant to your story and how it relates to our Southern Lesbian Herstory Project?

CMB: Being a Southerner is a partly why I stayed in church, too. You know the church is deeply rooted in the Southern culture. All kinds of churches were. However, growing up in the Black church in the South, church would be where I would plant myself. The MCC is the church of choice, I mean, because I can be most of who I am there. I can be out gay, I can be out Black, I can be out as a feminist, as a lesbian, as a womanist, and be embraced in MCC as those things.

Then there’s the sexism of Black male ministers. Black churches still have a problem with women, believe it or not. Thank God that’s changing. In a week’s time, I was in two Black churches, both Baptist, one of which the pastor will not let women, any woman, come to the pulpit. If a woman is going to preach or to speak at that church, or do anything, there’s a podium on the floor with a microphone, and he will put her there. Only men come to the pulpit. In Michigan, at Jean’s mother’s funeral that was still true. I spoke to the family. He did not invite me up. He pointed me to that lectern on the floor. I went where he said because I was not going to make a scene at my Aunt Loretta’s funeral.

Just a week later, I attended a funeral in Spotsylvania, Virginia. A Black preacher there had died, and there were Black women clergy in the room, and on the roster. Thankfully, when one in the audience asked to speak, the pastor extended his hand to help her up the step, to put her on the podium in the middle of the pulpit, the way it ought to be. I thought, “Wow, what a difference.” At a funeral, this man in Michigan would not allow a woman to come up to bring greetings, to read, to let loose, or anything. At this other church in Virginia, when a woman wanted to express her condolences to the family, she was invited to the pulpit. Unfortunately, a lot more are like that first preacher.

LF: Do you sense that the positive changes are different in different parts of the country, or is it just hit or miss? In other words, would the South be leading on that issue or not?

CMB: I think that people grow at various levels and paces all over the country. I think that there are pockets of really inclusive, Black preachers in every community. Sadly, they are far and few between; they are not the standard. They would be in the minority. I think that’s true everywhere. Every area of the country has some reference. Even Tulsa, Oklahoma had a progressive presence. People like Bishop Carton Pearson, who used to be on the far-right, is now far left. He got kicked to the curb by the evangelical groups in this country, of course.

When I was in Tulsa, there was a wonderful group, an organized group of clergy, interdenominational and multi-faith, that would gather to do all kinds of little things, even in the gay community center. They welcomed religious and nonreligious folk and supported the whole community. It was amazing to see at lesbian and gay pride celebrations representation from the Jewish community, from Wiccans, and from Christians of all denominations. There are pockets of progress everywhere, thank God. But, unfortunately, the resistance is also strong everywhere.

LF: Do you want to end on any particular note?

CMB: Basically, the only thing that I want to add would be that I feel blessed that I came through at the right time to help make the world more integrated. In our community, then, as a teenager coming out of high school, I went to a college that was predominantly white. I didn’t have to experience what integration was like because I graduated from a Black high school at a time when everything was segregated. I went to college just as things were opening up. I was the first Black female in my dormitory in college. I continued and I graduated from that college. I’ve been back for my college reunions. It’s a growing school. There’s a largely Hispanic student body now. They are making attempts to be more inclusive. That’s something that I support. I think, for me, that being in the MCC has meant forging ahead a vision, a shared world, and a shared leadership in the world that Black, white, gay, and straight can work on together. That’s important to me, rather than isolating to be comfortable.

LF: I appreciate all of your work and it’s a wonderful what you have done, and what you are doing, putting yourself in those positions to see that vision come true. It probably was uncomfortable for you quite a lot. You are very much appreciated by a lot of people, Carolyn.

CMB: That’s true, it was. And thank you, Lorraine. I appreciate you and the friendship over the years, and all of my experiences in Atlanta.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Interviewed for Making Gay History , January 26, 1991. Interviewed again November 10, 2022, available to Patreon subscribers.

“PAD Sacred Sharing,” from 2017 MCC Conference.