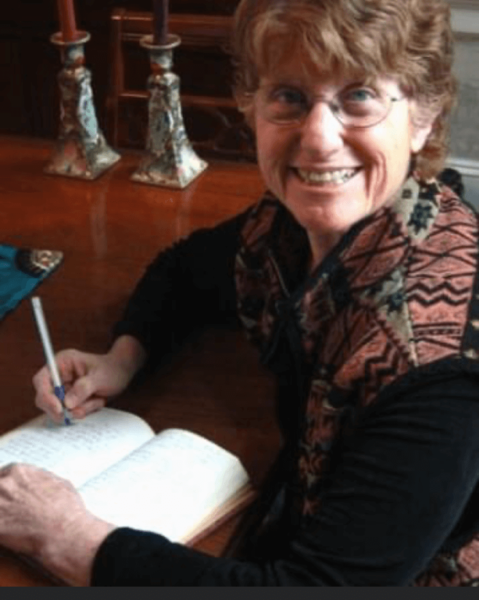

Barbara Esrig: Writer, Oral Historian, Nurse, and Cook Extraordinaire

Interview by Rose Norman in Melrose, Florida, on November 11, 2012

About this Interview

Barbara Esrig was a founding member of the Southern Lesbian Feminst Activist (SLFA) Herstory Project. She interviewed many lesbian-feminist activists for the project, wrote stories about them for Sinister Wisdom, and coedited two of SLFA Herstory Project’s special issues of Sinister Wisdom: “Hot Spots: Lesbian Space in the South” (vol. 109), and “Deeply Held Beliefs: Spiritual/Political Activism of Lesbian Feminists in the South.” She died of cancer on August 26, 2023. Barbara would have loved that August 26 is also the anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving women the right to vote.

Barbara Esrig was born in 1947 in New York City to a young, unmarried, Jewish woman who gave her up for adoption. Barbara has written about growing up in New Jersey, adopted by a wealthy Jewish couple, who soon divorced; and of a second family that her adoptive mother made with her stepfather, with whom her mother had two sons. Barbara writes that she felt she had more in common with the family servants. Barbara married a man named Esrig in 1967, giving birth to two sons in 1969 and 1970. The couple divorced in 1973. Barbara and the children promptly moved to San Francisco.

Barbara starts the interview with her time as a lay midwife in Eugene, Oregon, where she moved to from San Francisco, inspired by the midwifery movement. In 1979, she moved to Gainesville, Florida, with Oregon friends who had lived in Gainesville.

Biographical Note

Born in New York City in 1947, and raised in New Jersey, Barbara Esrig lived in Boston, Massachusetts; Ohio; California; and Oregon, before moving to Gainesville, Florida, in October 1979, where she lived for the rest of her life. She said, “writing has been my vehicle, my lifeline.” For twenty years, she was writer-in-residence for arts in medicine at Shands Hospital, taking oral histories from the patients there, listening to amazing stories and learning about their journeys.

(Read full bio.)

Barbara came out as a lesbian almost as soon as she arrived in Gainesville. She decided to make Gainesville her home when she discovered that she could get a registered nurse (RN) degree there in less than a year.

In that Southern university town, Barbara found a supportive group of lesbian feminists with whom she bonded, a bond that remained for the rest of her life. They became particularly close through work with the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, where she worked for some years. Following this work, Barbara became a psychiatric nurse, working with uninsured, indigent, and incarcerated patients until 1997, when she was critically injured in a head-on collision.

Barbara’s miraculous recovery from those injuries–she broke 164 bones and was declared dead at the scene–is a story in itself, told briefly at the end of this interview, and recorded for StoryCorps. After she was able to return to work, she became writer-in-residence for arts in medicine, collecting oral histories of patients at Shands Hospital in Gainesville.

In recent years, Barbara connected with her birth family when siblings found her through a DNA database search. That is when she learned that her mother and birth family were all from Michigan, and that she looked a lot like her birth mother, Becky. Barbara has written about this experience as well.

Barbara Esrig was an outstanding cook, writer, storyteller, and generous host to many a potluck or other celebrations where all of her talents would shine. Friends have collected some of her writings, which was posthumously published in a limited edition. Barbara had already arranged publication of In Just a Second, her illustrated, children’s book.

Rose Norman: This is Rose Norman, and I’m interviewing Barbara Esrig in Melrose, Florida, on November 11, 2012. Barbara will talk about her lesbian feminist activism in Gainesville, Florida, where she moved in 1979. [Melrose is one of several towns surrounding Gainesville.]

Barbara Esrig: My feminist activism started when I was in Eugene, Oregon. I was a lay midwife attending home births. Back then, ten percent of births were done out of the hospital. I was with a group of six women. We had moved together from San Francisco in 1976. I got my nursing license [LPN, a one-year, practical nurse degree] in San Francisco, but I had put my nursing license in the bottom drawer. One reason I did that: California had a really strong, medical lobby that outlawed home births.

Midwifery in Oregon

When I moved to Oregon, things were a lot looser. I still didn’t want to be a nurse midwife because there were too many restrictions. Within a couple of weeks of moving there, I and a group of women who wanted to do home births found that we had a synergy. The politics there agreed that women should be in charge of their birth process. The hospital made it a medical issue. We believed it was a natural thing, and that women should have control over their bodies.

We started our training and delivering babies at the same time. It was pretty wild. We all had some medical background. I was a nurse. We were learning from a nurse midwife named Marion. She was teaching us about home deliveries and complications. We worked with a doctor as backup, this wild doctor who worked at the naturopathic school. He had worked for the doctor at Stephen Gaskin’s farm in Tennessee, known as The Farm. We also worked with a pediatrician.

It wasn’t flaky midwifery in Oregon. It was really good prenatal care,

a fabulous home birth, and postnatal care.

One of the things really important to us was safety. When we did prenatal care, we made it very clear to patients that if the woman really needed to go to the hospital, she would go. We would not be her midwife if she wanted home delivery against our advice. It wasn’t flaky midwifery. It was really good prenatal care, a fabulous home birth, and postnatal care. We instructed about Lemaze for prenatal, and about La Leche for nursing, all kinds of things. The whole thing cost the pregnant woman $100. That included two midwives and all the prenatal and postnatal care. It was wild. And we did a lot of births. Our percentage of women needing hospital care was something like two percent, and a lot of that had to do with good prenatal care. I believe in women’s choice about where their birth should be.

My midwifery partner was a lesbian, Clair Englander. She lives in Puget Sound now. She was really involved in the lesbian community. I really, really wanted to come out in Eugene. But back then, on the West Coast, things were a lot more radical. I was living in a commune with men and women. I had been with men and women before, bisexual. Clair just didn’t want to bring me out. We’re still really good friends. I just saw her a couple of months ago when I was up in Seattle.

Moving to Florida

BE: This group of people I was with had lived in Gainesville before, and they wanted to [move back there]. I really didn’t want to, but I did. Before that, though, I have to say that there was a woman in Eugene. Her name was Moon, and she had “alternatively” fertilized herself with a turkey baster. Clair and I were her midwives. When Nelda was born, there was a whole community of lesbians supporting her. The idea of lesbians wanting to have children was pretty radical. When I moved to Florida, the lesbians here could not fathom why any lesbian would want to have a child.

The other thing I want to say about what was going on there [in Eugene] has to do with a lesbian who died, and who willed some money that she wanted distributed to women’s organizations. We needed equipment, like speculums, and we went to a meeting about this [money granted]. We had to prove ourselves as feminists, and that we were against the medical establishment, doing this to give power to women. This feminist belief in allowing women to be in charge of their own health care segued into what I wound up doing in Gainesville.

Gainesville was a really different environment in the lesbian community.

The group of people I moved with included a man I was with, Bill. The relationship really wasn’t working. It was working enough that I moved to Gainesville. And then, I knew I wanted to come out as a lesbian. Within three weeks of moving to Gainesville, I came out as a lesbian. I called Clair to tell her, and she had hooked up with Moon by then. Eventually, Clair was artificially inseminated, too. Nelda wound up being brought up by the lesbian community, with twenty or so women who shared child care. The sperm donor was a gay man who said he wouldn’t interfere with the child’s care. Clair inseminated with his sperm, too. She had a daughter, so the two girls were half sisters.

Gainesville was a really different environment in the lesbian community. I had contacted a couple of midwives in the lesbian community, Randi Cameon and Joan McTigue. Both of them were trained as physician’s assistants. Both were working at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center [GWHC, 1974-97]. I worked with Joan doing some home births. Joan was breaking up with her husband. I was breaking up with Bill and coming out.

I came out, and that night, I met Connie Jylanki and Corky Culver [important in the lesbian community]. Immediately, Joan took me under her wing and brought me to the GWHC, which was both a women’s clinic and an abortion clinic. [Joan was politically radical, but she was not a lesbian.] At the time, Roe v. Wade had passed, and people were really positive about it. The religious right had not yet taken it as their issue. There were a few, but there wasn’t the same kind of contention as there is now. In fact, the medical school had a rotation where physicians would learn how to do abortions. The doctors who were doing the abortions were mostly medical students. We really taught them how to treat women respectfully. They became the best OB-GYNs [doctors who specialize in obstetrics and gynecology] in Gainesville. [She names some: Tom Tyler, Brad Williams. She mentions some women doctors that she doesn’t name.]

Being a nurse, I did take my license out of the bottom drawer. I was doing women’s health care and assisting with abortions in the recovery room. I was really radical, and lots of CR [consciousness raising] was going on at the clinic, lots of workshops and discussion about being in control of our bodies.

It initially started with mostly strong feminist women, and then, over a short period of time, several women who worked at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center all came out at the same time. Lynda Lou Simmons, Pam Smith, and Marilyn Mesh were working on a watermelon farm out in Archer [another town near Melrose]. Somehow, they all just dropped the males they were involved with and hooked up with women. We were all feminists, and the work at the GWHC radicalized people into lesbian feminism. There was some backlash against abortions, but from the beginning, we were very much supporting each other.

At the same time, I was working there [at the GWHC], and I was still doing the home births. Randi and Joan were also doing home births. Cheryl LaMay did a couple of births with me. She was in medical school at the time. I was also hooked up with some lay midwives living in Gainesville. In Oregon, we had started doing home births in 1976. In Gainesville, they had just started in 1979 and ’80. Oregon was a lot more progressive than Gainesville in terms of the home birth scene. Some were doing births by themselves, which is really dangerous. Also, the whole climate for home births was really different in Gainesville. Pretty much, the norm was the granny midwives, the African American midwives, who had been doing it for many years.

RN: I’m not following you here.

BE: Midwifery has been around since day one. In Gainesville, for the white women midwives, it was more of a political act. Whereas, for the grannies, it was more of a tradition–and sometimes an economic decision. There was still a lot of segregation. Most of the women in the African American community were having children at home.

RN: Even in an urban area like Gainesville?

BE: Gainesville wasn’t all that urban. [Many people lived in the small “spoke” towns outside Gainesville.] Alachua General Hospital, the main hospital in Alachua County, was not desegregated until the early 1970s.

RN: These lay midwives were coming at it from a “hippie” perspective. Were they learning anything from the granny midwives?

BE: There was a separation there. It wasn’t intentional. It was a political movement within the white hippie community of not wanting to deal with the hospital regulations. In the African American community, they were driven by a combination of economic necessity and tradition. Home birth was the way it had always been done. When it became illegal, the granny midwives were grandfathered into the law, and they were exempt from the legal restrictions on midwifery. The law didn’t want to deal with the African American community.

RN: What was illegal, home births or midwifery?

BE: The lobbies caught up, sort of like the lobbies in California. It became illegal for the midwives to do a home birth.

On the first floor, behind the boiler room, was a place called “the annex.”

That was for “coloreds,” as they called them.

Alachua General was a three-story hospital, and it had been segregated. I know this story because of doing oral histories with people who were born there. I knew Black women as well as white nurses who were there during the desegregation process. The way the hospital was set up, the main floor was for white women, the second floor was the pharmacy and medical services like radiology, and the third floor was labor and delivery for the white women. On the first floor, behind the boiler room, was a place called “the annex.” That was for “coloreds,” as they called them. There were two large wards: one for males, the other for females, separated by sheets/curtains. All the Black women were there. You could have a woman with malaria separated by a curtain from a woman in labor. There were only Black nurses in the Black annex. The white nurses weren’t working with the African Americans.

Black women labored on the first floor, but delivery was on the third floor, and there was a hand-operated elevator. A woman at end-stage labor would be going up in this elevator, and sometimes would give birth in the elevator or in the hallway. That was the first unit that got desegregated because people complained about it.

I spoke to the head nurse of that obstetric unit. She said that she was always against segregation at the hospital. That’s why most African Americans did not want to go to the hospital.

[Alachua General Hospital was the first community hospital in Gainesville, started in 1905. It was acquired by Shands HealthCare in 1996, renamed Shands. It closed in 2009, replaced by a new building.]

When I first interviewed at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, they knew I was doing midwifery. They wanted to be clear about my feelings about abortion. My mother had had an abortion in the 1950s, and she had always given a lot of money to Planned Parenthood. She was clear that it was women’s rights. For me, it wasn’t a difficult transition from midwifery to abortion. It all had to do with choice.

We were doing all kinds of women’s health care, infection checks as well as abortions. We were teaching doctors about speaking to women in a respectful way, putting mittens on the stirrups, warming up the speculum, showing women their cervix. We did all of that at the women’s clinic. There was also a really strong contingency of lesbian political work going on there. We were lobbying and marching. On Thursday night, we’d all go dancing.

RN: How is lesbian feminist activism coming out of the Gainesville Women’s Health Center?

BE: We were marching, doing Take Back the Night actions. We were involved in a lot of education about women’s health care and about taking care of our body. That was the bottom line.

RN: A doctor friend tells me that lesbians tend not to get pelvic exams, and that they should. Did you try to get lesbians to do that?

BE: Yes, we did. I think that women who have a really hard time with pelvic exams, lesbian or not, are women who have been sexually abused, such as child sexual abuse, and other. We did a lot of education about that, too.

I was living with three women, three lesbians, while I was working at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, before I left. And you know, I was still really ambivalent about living in Gainesville. Even though I had gotten into the women’s clinic, I still only had one foot in the door. I thought about living with a woman that I had a crush on. Then, I traveled to Oregon, and I got my old house back. Then, I came back to Gainesville to get my stuff, and things happened. I never went back [to Oregon]. One thing that happened was that I decided to get my RN license. I already had an LPN license from California before I moved up to Oregon. I moved out to Gainesville, worked at the clinic with the midwives, went back to Oregon, and came back here to Gainesville. I wound up starting RN school. And after I started RN school, I moved back to our house with lesbians again. That was in ’81. I was only gone for four months, I think. Maybe three months.

I Fell in Love With Gainesville

Suddenly, it just all made sense, why I was in Gainesville. I fell in love with Gainesville. Even though I came out, I hadn’t come into a relationship with a woman. I was involved with a lot of women that were just coming out. I went to RN school, and then, I moved to the Red House. The nursing program was a bridge program. I already had my two-year degree, my LPN, which allowed me to get the RN degree in a year, in thirteen months. [When I decided to stay in a Gainesville and get my RN,] I moved back in the house shared with women who worked at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center [all lesbians]. One of them eventually became president of NOW [National Organization for Women]. Everybody was pretty radical back then. The week after I finished my RN, I moved out to the Red House. I had been focused on nursing school, but there was a lot of stuff happening in Gainesville.

Let me tell you, right at the end of that thirteen months of school, I got into a relationship with Sandy Cosgrave. I was a wild girl back then. And there were lots of parties going on, lots of socializing going on at the Red House.

Sandy was living in Gainesville. She had a big, New Year’s Eve party, a lesbian New Year’s Eve party, and we may have gotten together then. It was sort of my first official [coming out]. It wasn’t the first time I had slept with a woman, but it was the first time that I called it a lesbian relationship. I had already come out a couple of years before. It was hard even though there were lots of opportunity [laughter]. I was just shy.

She asked me what I was doing. I told her that I was buying paint so that I could fall in love.

When I was with Sandy Cosgrave, it wasn’t romantic. It was more sort of an introduction to lesbian sexuality, and she was a good teacher. We were doing all kinds of witchy stuff, like circles, and feminist stuff, like camping. A whole group of us would go to the beach, and we’d have these middle-of-the-night circles. We’d get together at any opportunity to have parties. There was a lot of socializing going on then, just about every night. I mean, it wasn’t like only a weekend thing. There were lesbian Halloween parties, all kinds of stuff. The lesbian moms first started to get together and organize. A lot of people were going over to the Pagoda. There was a really big music thing that was going on, women’s music. Sandy Malone and Ruth Segal were partners then, and they had amazing musicians coming all the time. It was just a hub. It was really, really active.

[Ruth Segal and Sandy Malone had a production company called Womyn Producing Womyn bringing in musicians, comedians, and lesbian artists of all kinds.]

There was a women’s bookstore called Iris Books. Gerry Green ran it with her partner [Carol Aubin]. It wasn’t in the same location as the bookstore, Wild Iris, is now. When it moved, it didn’t move far. It went from Iris Books to Wild Iris. [Gerry Green and Carol Aubin owned Amelia’s Books, 1977-82, and this may be what Barbara is remembering here. Dotty Faibisy and Bev White bought Amelia’s Books, and they renamed it Iris Books, then later,Wild Iris Books. It lasted 1992 to 2017.]

There were lots of things going on then, lots of marches. I moved into the Red House, and I went to Sears to get paint, and I ran into Sallie Harrison. She asked me what I was doing. I told her that I was buying paint so that I could fall in love.

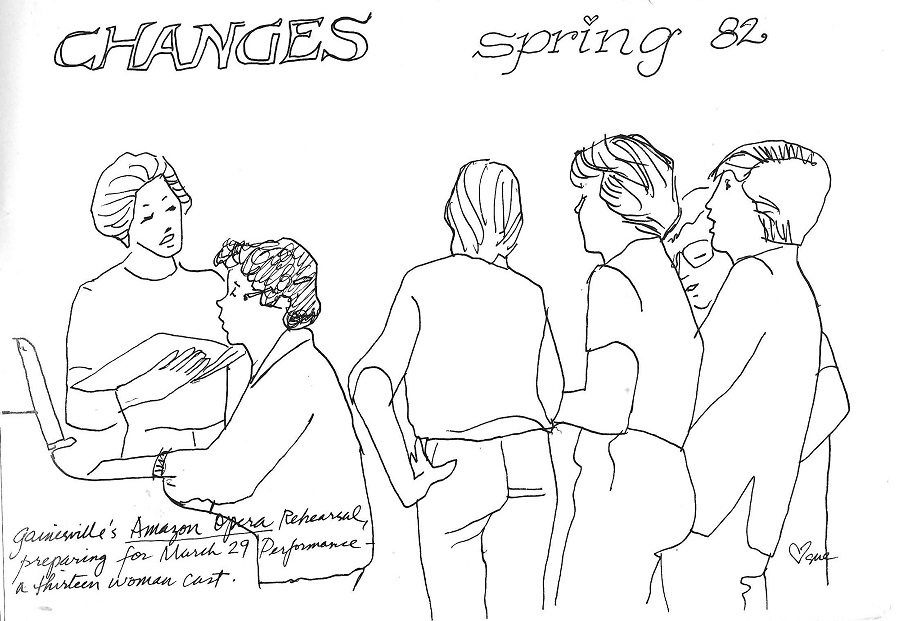

BE: There was a sort of Renaissance, and there was a couple of lesbians, a woman named Megan, and Linda Wilson [also known as Rock Starr]. They were both musicians, and wrote this opera, a sort of operetta, about Amelia Earhart. [It was called Amazon Opera and was performed on a Monday night, March 29, 1982, at the Hippodrome, Gainesville’s state theatre. It was not filmed.] They produced this operetta in the Hippodrome, and that was wild. Here was this wild, lesbian operetta performed at the state theatre. Linda Wilson wrote it, and her partner Megan performed in it. It was just wild. We just sort of took over the state theatre downtown.

They’re still together [Linda and Megan]. That was in 1982. But the thing is, it was very, very easy to come out in Gainesville in the 1980s. There were lesbian teachers in the nursing school. All of us were very politically active at the nursing school. [Gerry Green taught in the Santa Fe College nursing program that Barbara joined.] It was very easy for me to be out as a lesbian. I later got a degree in Anthropology at the University of Florida. The nursing school was at Santa Fe, Florida.

Feminist Spirituality

When Sandy [Cosgrave]and I got together, I was living at the Red House. We started to do spirituality work together. A group of lesbians went down to Cassadaga [Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp] to learn natural law from Eloise Page. It’s a camp near Deland, about a hundred miles from Gainesville. Every Friday night, a group of lesbians would go there to take natural law classes. Cassadaga is a spiritualist community. There are psychics that live there, and there are little houses. People own their house, and the camp owns the land. Eloise Page came down in the 1948 from Michigan to start this community. There were lots of psychics there, which really fit in well with lesbians [who might be interested in spirituality, as many Gainesville lesbians were].

It became a really commonplace thing. You know, Flash [Silvermoon, a psychic] was in Gainesville. She didn’t go to Cassadaga. She was already doing psychic readings, and she still does [Flash died in December 2017]. She was doing Tarot card readings. She made up her own deck of Tarot cards. A lot of people were into Tarot cards, psychic readings, doing circles, and other feminist [spirituality] things.

About three carloads of lesbians all went down to Cassadaga

to study natural law every Friday.

This was going on in Gainesville. The people in Cassadaga were an older group. Eloise died in 2007 at the age of 96. The psychics there were not part of the hippie community. They were older women and a few men. It was a really interesting place. You can still go down there and get a psychic reading. We went there every weekend. Every week there were a group of us that went in a van. It was Sallie [Harrison]; Ann Gill, a lesbian who has training in polarity and who was doing alternative health stuff; Cheryl LaMay; Sandy Cosgrave; and I. Sandy wound up with Marcia Zeimer, and they lived in Cassadaga. Sandy became a psychic in Cassadaga, and she lived there for several years.

About three carloads of lesbians all went down for every Friday. It was really a commitment because it was a hundred miles each way. I was with Sallie [Harrison] at the time, doing political action. We were trying to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, we were doing marches there, and going to Tallahassee. We were doing lots of Take Back the Night stuff, and we were doing the Peace Walk. Did Corky talk about the Peace Walk? I was involved in that. And there was just a pretty amazing flavor of Gainesville that was, you know–we sort of became a hub of feminism.

[See Corky Culver and the Women’s Peace Walk, 1983-1984.]

The Lesbian Variety Show

There was also the Lesbian Variety Show that was going on there. That started in the mid-1980s, and it’s still going on. We have it every year. [See Barbara Esrig, “Gainesville’s Lesbian Variety Show: Not Just Another Talent Contest,” Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017): 139-43.] And there was this great song, “Gainesville Dykes,” you know? I think you probably saw it performed at Womonwrites [Womonwrites: the Southeast Lesbian Writers Conference]. “Whether you live in Melrose or Archer or Hawthorne, you’re still a Gainesville dyke.”

[Ruth Segal, Beckie Dale, Pam Smith, and Lynda Lou Simmons performed the song “Gainesville Dykes” to the tune of “Stayin Alive,” at the Lesbian Variety Show. The lyrics were published in Sinister Wisdom 109 (Summer 2018): 29. Ruth Segal and Beckie Dale also performed it at Womonwrites: the Southeast Lesbian Writers Conference one year.]

There were always country dykes that came into town. The action with that kind of politics was more in Gainesville. Out in Archer, that was the watermelon farm, and there were dykes out there. There were obviously dykes in Melrose, not as many as there are now. The Red House women were out there [in Melrose]. That was definitely a central place. And people went out to the Pagoda, in St. Augustine, on Vilano Beach, about an hour from here. Nancy Breeze was working at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, and then she moved to the Pagoda. She’s one of the people that we all went dancing with on Thursday nights.

Jewish Lesbian Group

We started a Jewish lesbian group that became pretty important. We still have seders every spring, lesbian seders. It started off because there was anti-Semitism in the lesbian community. It became a thing that Jewish women were always loudmouths, that they were always the ones that were over-talking everybody, or that they were pushy. The group started around Christmas, because Christmas is a really difficult time for Jews. [Laughter] I always felt it. That’s what happens with support groups. You find out that you’re not the only person who feels that way.

We got together and met at Christmas, somewhere around 1985. We had already established a lesbian writers group, which I was involved with, which was great. It was kind of an offshoot of that.

[See “Marilyn Mesh and Barbara Esrig, “Jewish Lesbian Support Group and Seders,” Sinister Wisdom 124 (Spring 2022): 117-20. They say that it started with a Jewish consciousness-raising group in 1981.]

There were actually quite a few Jewish lesbians in Gainesville, maybe eight or ten. The first group started talking about Christmas, and about what our experiences had been as children. We started talking about itches in the community that we felt. We talked about our experience with Jewish education. Education was always important in a Jewish family. That was the number one thing: to be educated. Jewish parents always wanted their kids to go to college.

RN: You must have broken with your family over that if you just got an LPN degree to start with.

BE: I had a two-year thing. The truth of it is that the education… My mother went to Vassar, and my brothers both went to Tufts. My mother’s attitude to me—you know that I was adopted—was that my job was to marry well. As women, our job was to marry well. I definitely broke from that! I didn’t marry well. [Laughter] And then, I had two kids. I got married in 1967, and by 1972, I was a single parent.

Barbara’s Five Last Names

RN: Was that who Esrig was?

BE: Yeah, that was Esrig. The reason why I kept that name Esrig was that my stepfather, who was my adoptive mother’s second husband, and I did not get along. I didn’t want his last name, Safran. I didn’t want to keep his name. And most of the time that I was married, all until the last six months, I think, or four months, Mark, who was my husband at the time, had his stepfather’s name, which was Fagan. He couldn’t stand his stepfather, either. Mark’s dad had had died when Mark was only six months old, and he never knew his father. His father’s last name was Esrig. It was his political action to take his father’s name, whom we never knew. When we split up, I didn’t change it. Some of it was because I didn’t know what to do with the kids and the name, not wanting to have a name different from the kids. I got divorced in 1973, and the next day I moved to San Francisco.

RN: Originally, your name was Mark’s other name, Fagan?

BE: Actually, my name was—I was born with the name Linda Kayle. And then, my mother adopted me with her first husband. I went from Linda to Barbara Blake. That was her first husband’s name. From Linda Kayle to Barbara Blake. Then, she got divorced six months later. When I was three, she married a Safran. From three years old on, I had his name, Barbara Safran. When I got married, it was Barbara Fagan, which Mark hated. Then, it became Barbara Esrig, and then, I got divorced.

In 1986, I bought a house, which is the house I live in now. It was a group decision. I had lots of lesbians who came by and checked out this place. It was really a fabulous house, but it was sort of a potential. I was falling in love with a potential. It was a fixer-upper. What I did in relationships, I think, was fall in love with potentials. Like, this person would really be a great person “if only…,” and, you know, he’s a drunkard.

So here was this house, and that became my main focus. What happened in this house was that it became the place where we had Seders, lesbian Seders, Jewish dykes. We had lots of potlucks, and the house became a center of community. People wanted to have their birthdays there. They wanted to have Thanksgiving dinners there. It just became a central place. Then, I got into a twelve-year relationship that started in 1990.

Community Support After Head-On Collision

When Marcia and I got into this twelve-year relationship, I was working a lot. At that point, I was a psychiatric nurse. I was a psychiatric nurse all through the 1980s. I wound up doing psychiatric home care. In 1997, I got into a head-on collision. The only reason I bring this up is because there was this amazing community coming together, which really saved my life. The way that that happened was sort of beyond me. I got into this head-on collision.

They called Marcia from the hospital. She wasn’t my power of attorney yet. A couple of other women met her at the hospital. They told her to bring somebody with her. My accident report said “Fatality,” so I was really in bad shape. Three women were there at first, and by the morning there were a hundred women from the community in the waiting room. You know, it was a lesbian thing. They came, and sat, and stayed. It was a pretty historical event at the hospital.

I mean, it wasn’t a time to be in the closet. Marcia definitely wanted to be the person known as my partner. There were all these lesbians who came. They did circles in the waiting room, and there were Tarot readings to tell the doctor what to be looking for. Dotty Faibisy, who was the director of Wild Iris at the time, put this giant schedule up with two-hours slots. Women signed up. There were always two women and a high-tech nurse by my bed because I was a nurse. I needed really one-on-one care, which the hospital really couldn’t ordinarily provide.

I was getting fourteen units of blood in one arm and acupuncture in the other. It was sort of Eastern and Western medicine going on. There were people doing Reiki on me, and crystals were hung from my IV poles.

But there was always a high-tech nurse friend, and there was another friend who took care of the caretaker. It was a real feminist, lesbian paradigm that happened in the hospital. The hospital was blown away by what they saw. Ann Gill was doing polarity, Pam Smith was doing acupuncture. I was getting fourteen units of blood in one arm and acupuncture in the other. It was sort of Eastern and Western medicine going on. There were people doing Reiki on me, and crystals were hung from my IV poles. I had my fiftieth birthday in the hospital, and they wallpapered the walls not only with get-well cards, but also with birthday cards. Womonwrites: the Southeast Lesbian Writers Conference did a little video, and I got the video because that was the only Womonwrites I missed.

[For more info on Womonwrites:the Southeast Lesbian Writers Conference (1979-2019), see Sinister Wisdom, volumes 93, 116, and 124.]

Then they wound up having a second Womonwrites in the fall that year [1997], I didn’t miss that year. At the conference, they interviewed all kinds of women who wanted to wish me well. The accident was April 14, 1997, and I was still in the hospital when Womonwrites happened in May. Women were bringing me t-shirts, lesbian t-shirts. I got the Womonwrites t-shirt that year. And how I would connect those two things just sort of showed the cohesiveness and the feminist paradigm of how to come together when there’s a crisis, which was very much Gainesville.

I always say that it had less to do with me, with them all coming together, than the group thought that we’ve got to take care of this situation in our own way. There was the medical model, which I couldn’t have lived without. I broke 164 bones, and I had a bad head injury. But there was another part that was equally life-saving, which was this group energy. They thought their job was to keep me alive and to make me well. And it worked!

And the hospital noticed that it worked. They said that they had never seen anything like that. The day that I left, the nursing supervisor came in. She said that what went on in that room, everyone was talking about it, people in the doctor’s lounge, people in the nurses’ stations, people in the cafeteria. The only time the TV ever went on was when Ellen DeGeneres came out. I was in the hospital during that episode. That day, some women came in and said to me, “You need to turn on the TV.” And there it was, and it was like, “Oh, my God, this is another miracle!” [Laughter] Ellen came out on TV. It was a sign of this amazing experience.

My hospital stay was a real experience for the doctors, for the nurses, for the housekeepers. Everybody wanted to be in that room because of the lesbian energy, and it was lesbian-feminist energy.

Ultimately, they brought the Arts in Medicine program into the hospital, and I became part of Arts in Medicine. That was at Shands Hospital. I had been at Alachua General Hospital. Shands Hospital was the big, teaching hospital in Gainesville, and it had Arts in Medicine there. I had some lesbian friends who were in Arts in Medicine, but I didn’t really know what it was. A year and a half after the accident, Shands Hospital bought Alachua General Hospital, and they brought Arts in Medicine in there. They called me, and asked me if I would be a part of it because folks were going back to the meetings and talking about what had been going on in the hospital and with me. It became one of those stories. I just started doing oral histories, which is what I’m doing now, for the last thirteen years.

My hospital stay was a real experience for the doctors, for the nurses, for the housekeepers. Everybody wanted to be in that room because of the lesbian energy, and it was lesbian-feminist energy. It was a belief that we had strength in numbers, and that we come together and support people that need to be helped.

Womonwrites had a lot to do with that, too. I was getting all kinds of cards from people, and phone calls. I was still in the bed when Gail [Atkins] and Gwen [Demeter] got into that awful car accident. [Gail and Gwen were Womonwrites friends from northern Mississippi who were badly injured in a car accident. Both recovered.] That was another time when the community came together. I was calling their hospital, and it was like a review of my accident. So much that happened to Gwen had happened to me, like this feeling of, “Oh, my God, she’s going to die!” kind of thing. And potential complications. I felt like I understood it from the inside. It was really amazing. I would write emails and tell people what was going on. It was kind of a surreal experience. I think that the Womonwrites women definitely had their part in my healing, and there were a lot of Gainesville women that regularly attended Womonwrites that were directly involved.

Arts in Medicine started in about 1990 in Shands Hospital, and it would have been going on there for quite a few years when I started. The website is https://artsinmedicine.ufhealth.org/ Alachua General Hospital called it Arts in Healing, but it is the same thing, same group as Arts in Medicine. They asked me to be the writer in residence.

That accident retired me as a nurse. It also allowed me to be much more creative in a way. Working in the hospital doing patients’ oral histories, hearing their stories, it was a way of giving back what women did for me, which was to remind me of what I was, that I wasn’t just a bunch of broken bones. In every room, there’s a story. I have enjoyed doing oral histories. That felt really lucky and an honor to do that, and I get paid for it. It’s my job.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Barbara Esrig, “The Gainesville Women’s Health Center, 1974-1997,” Sinister Wisdom 93 (Summer 2014): 42-43.

Barbara Esrig, “A Nurse’s Experience in a Progressive Women’s Health Center,” Sinister Wisdom 93 (Summer 2014): 50-52.

“Tell Me a Story,” documentary film by Hemal Trivedi, https://youtu.be/1dJ5KEP1P5I

Do you have something you’d like to add to this tribute?

Take the leap and share the lesbian love.

Or you could write a few lines in tribute to another lesbian.

Just contact SLFA.