Águila Talks about Her Memoir

Interview with Maria Cristina Moroles, Águila, via Zoom by Rose Norman, April 2, 2024.

- Maria Cristina Moroles (Águila): Building Sacred Community on the Land

- Review of Águila: The Vision, Life, Death & Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains

Rose Norman: Today I am interviewing Maria Cristina Moroles, who was known as SunHawk for many years, and is known now as Águila. That name was given to you by a medicine woman, or by someone else?

Águila: Yes. One of my teachers, a ceremonial leader, an elder gave it to me.

RN: Águila means “eagle,” and it is a great honor to be called that.

We first met in 2014 when I interviewed you by phone for Landykes of the South. At that time, yours was the only woman of color land we could find in the South. Now, you have written your life story in this book, Águila: The Vision, Life, Death and Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains, which came out this year from the University of Arkansas Press.

Águila: I want to say that the book comes from fifty hours of transcribed tapes that totaled 450 pages. We selected from those 450 pages of transcripts for this book. Eventually, I foresee that more from those transcripts will be used for another book. That will be the whole thing.

RN: The book is coauthored with Lauri Umansky, who is an academic like me. She teaches history, and she directs the heritage studies PhD program at Arkansas State University. She moved to Arkansas in 2012. Having done a lot of interviews myself, I cannot imagine having fifty hours of interviews transcribed to turn into a book. That must have been quite a job.

Águila: That was Lauri that did that. It took a lot of convincing for me to take on that project. She was the third person to propose it. People had asked me to write the book for some time. She made it seem possible.

I have a very busy life. Right now I have a carpenter outside working on an outhouse. It’s an upgrade. I have an apprentice, I have a clinic, I make medicines, and I do all kinds of ceremonies. I told her there was no way to do a book, too. I’m living life. How am I going to write it down? I don’t have time. I’m too tired at the end of the day. I need to sleep. I need to rest.

I thought, “Oh, Creator is telling me, Creation is telling me, guiding me to do this.”

She convinced me. She said, “I will come to you.” This little, tiny woman, who looks like a little fairy, had been a ballerina when she was younger. She convinced me. She said, “I will come to you, and I tape our conversations. Then, I will type it up. We will go over it together, and since it’s a conversation, we will edit it into a book form.”

I thought, “Oh, Creator is telling me, Creation is telling me, guiding me to do this.” This is the third time. In our belief, if you want something, you have to ask that person three times. If it’s something big, if it’s a healing or something that you really want to learn from, or if I really want you to help me heal this wound, they need to ask three times. I was trying to ignore it [laughter] because I just couldn’t see how it would work. I really couldn’t see it. I didn’t see that I had the energy for it. But she did it! She put a lot of effort into it. That’s why she is the coauthor.

RN: I just edited a two-hour interview with you, and that was quite a job. She’s got fifty hours of interviews and is writing a book. it’s a good book, a very good book, impressive in a lot of ways. One of the things that impressed me was how it integrates the spirituality, which is so important in your life, with the harsh realities you have experienced.

The land that you settled, Arco Iris, that was really a tough thing to do. How much has it changed in those last ten years since I first interviewed you? Did you have running water then?

Águila: Ten years ago? Yes, we did. We put in running water and we redeveloped our spring when we first moved here. I was very young, in my early 20s then. I didn’t know a lot of things, and we were drinking water from a spring that would run down like 300 yards from its origin. That’s not clean water, because everything gets into that water, like the animals and bugs and all kinds of things get into water. So I learned more about how to do that. I found the origin of the water, and then, we eventually put in different tanks. It has a settling tank, and it has 1,000 gallon tanks.

RN: Are you living in town now?

Águila: No, we’re out on the land. I’ve lived at Santuario Arco Iris for almost 50 years at this point. We stayed on the Santuario side because the land we reclaimed in 2000 was not set up in any way and was under conservation. I have never lived on the 400 acres that was reclaimed in 2000 from Sassafras and is now the Wild Magnolia Land Trust. [This reclaimed land is about 400 acres that was donated to the nonprofit known as the Arco Iris Earth Care Project.] It did not have anything. We put the office over here where we have everything. [“Over here” is the intentional community now known as Santuario Arco Iris.] We have a little bit of everything. We have limited solar power and limited Wi-Fi. We had to get two Wi-Fi setups: one at the office, and one here at my house. The office is a little bitty storage building that you buy and set up yourself.

My assistant works at the office. She helps me with my personal running of the ranch, of the Santuario. There are so many things that have to be done online now.

Back to the water. Yes, the water is now piped in. We’ve got a capacity of 3,000 gallons, which isn’t much for a large community. We need to put in more storage tanks. The spring water runs until midsummer, and we fill up all the tanks. They’re continuously filling from the spring water. We hope to ride through until the water table comes back up and refills them. We’re very lucky and thankful for this incredible Ozark spring water. We have true Ozark spring water.

RN: Not the bottled kind. [laughter] Tell us a little about the community as it is now. You’ve got 120 acres that was originally deeded as women of color land from Diana Rivers and the Sassafras women. [See Merril Mushroom, “Arkansas Land and the Legacy of Sassafras,” (Fall 2015): 36-42.] In 2000, Diana Rivers, and whoever else was on the deed at that time, deeded everything on that side to your nonprofit.

Águila: Yes, the land was in a collective. Diana had already removed the other women off the collective, because they had abandoned it for some time. I would say it had been seven years, maybe, since it had been abandoned. It was being looted by locals, hunters, and different people like that.

Now we have 90 acres that are in our name.

We realized that something needed to happen, and Diana ended up trying to quiet the deed. “Quieting the deed” is what you do when there’s an absentee owner. There was one person left [on the deed], one woman, Shiner. She had been my partner for the first five years on the Arco Iris land. She had moved back to California, and she wasn’t here when it was being quieted. There’s a legal process that happens where they put it in the newspaper for thirty days. If no one steps forward, then, the person that’s quieting the deed gets to settle the deed to make it their own. She [Diana] was the original purchaser of that homestead, which was homesteaded by the original settlers and their generations.

What has changed? Tell me the question again because I’m a storyteller, and I get lost there.

RN: How has the land changed since I interviewed you ten years ago?

Águila: Now we have 90 acres that is in our name. We have running water in the house, but not all the houses have running water. My daughter [Jennifer] has a cabin here. She still ives in town, not far from here, twenty miles. [Jennifer was five years old when Águila moved to the land.] My son [Mario] has a cabin here. [Mario was born on the land.] I have two other resident stewards. We consider ourselves resident stewards. There are many stewards to this land that help in their own way. But we are residents.

RN: There are three houses on the land?

Águila: We have one, two, three—we have, actually, four houses and a bunk house, which is a combination of bunk house and clinic. [Águila is a practicing curandera, a traditional native healer and herbalist.] The bunkhouse has one room that is separated from the rest of them, which helps to keep them in order. I could bring a patient up here at any time, and this place needs to be kept in order. That has helped. We have a lot of space, a lot of little, different spaces.

RN: Do you still have an office in town?

Águila: No, I retired from town. It’s probably been five years now.

RN: What’s going on with the non-profit?

Águila: There’s a lot of movement with Arco Iris Earth Care Project, the nonprofit, right now and we’re in a period of growth. Our main job is stewarding the beautiful 400-acre Wild Magnolia Land Trust. We host a lot of programs, with youth through our environmental education programming, young adults in our internship program, and our local community through volunteer days and guided hikes. We just started a program called OUT in the Woods, where we host queer people and People of Color for community building and skill-building workshops. Our first one was during Pride Month and we had a lot of fun. We’ve also been collaborating with different departments at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Arco Iris has been cultivating a relationship with the University Multicultural Center, and we’ll be hosting another Dia de los Muertos ofrenda-making workshop while teaching students about the indigenous roots of the tradition. All of our programs are led through the lens of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) or indigenous earth care principles. Our biggest event of the year is La Caminata. This year was the 40th anniversary. We walk the boundary of the land we steward in a traditional blessing ceremony and pray for the health and well-being of our Mother Earth and community in the year ahead. It’s an exciting time for Arco Iris, and we have three employees now.

RN: I understand that at Santuario Arco Iris you have interns through Worldwide Opportunities for Organic Farms (wwoof.net)?

Águila: Their internship program is insured, and they keep track of things. The interns have to send us their application, their request, information on themselves, their experience, all that kind of stuff. The organization insures them while they’re here. The cost of being a member is very little. We started using that program, and we pretty much target LGBTQ people, and especially women of color in that community.

It’s not just organic farming that we do. They learn husbandry and sustainability skills for this land. It’s about indigenous sustainability skills. That’s what we teach. Of course, in organic farming, they also learn all kinds of things about being on a farm. They have to chop wood, clean out chicken coops, clean out goat pens, and take care of animals. There are a lot of different aspects. I wanted to do ours from the indigenous, Native American perspective, our perspective. As a two-spirit, I wanted to have a safe space for those people. Women of color and two-spirited have a hard time. We do have straight women of color coming, but mostly not. They’re vetted to try to see who’s going to fit in our community, which is a queer community.

RN: How long do the interns stay?

Águila: It depends on them. Starting this year, we only take interns who are twenty-one or older. We tried taking younger people and it did not work. Too much liability. They’re not mature enough, and lots of other reasons. We all decided as a community that it’s best if we get interns twenty-one and up, and that they have longer stays, from a month to three months, or to permanent residency, working towards permanent residency. We also have my apprentice, Artemis, a Puerto Rican woman, she’s 36 or 37.

I also have an executive administrative assistant named Elise. She does all the computer work and grant writing. She will type the letters for me, and I will dictate to her. She keeps me on track. They all do. Because I’m trying to do as much as I can in this lifetime.

RN: You’ve done a whole lot, too, and it’s really amazing.

Águila: It takes a toll on the body. I’m trying to do as much as it will allow me, while still taking care of myself.

It took me two years, my girlfriend and me, two years to save up the money to open the road.

RN: Living on that rugged land was tough. You were hiking in supplies when you first moved over there.

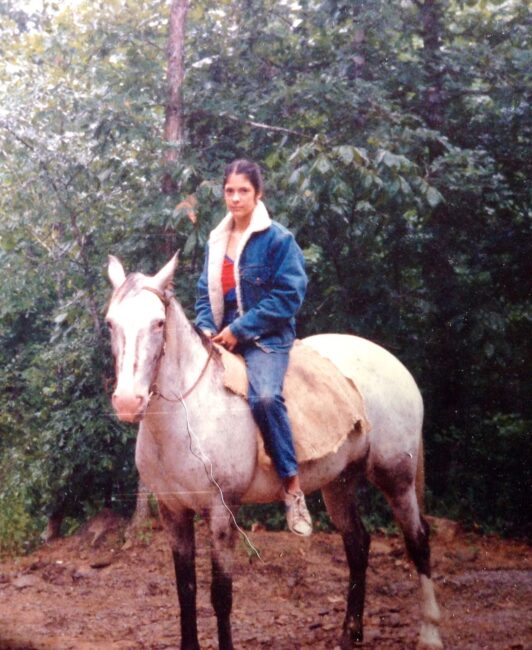

Águila: Yes. At first, my five-year-old daughter Jenny and I would hike from Sassafras to Santuario, which is actually a separate mountain. We would transverse Sassafras, go across Beech Creek, and hike up a very steep incline, 1,200 feet to be exact, to a bench where we settled here on Santuario. So it was an hour of hard trek.

Then, we got to the road. We found out that access changes with seasons. As the seasons change, Beech Creek becomes a raging river. I found that out from personal experience. I went with my little kid, and we’re walking down, and we would hear this roaring. There’s no passing, there’s no crossing, from that mountain. We had to go back to come up that road, which was a very old road that hadn’t been used in about two decades. It was rutted with ruts two or three feet deep. It had trees that were three to five inches in diameter already growing in the road. It was no longer a road, per se.

RN: Is Santuario the name of the nonprofit that owns the 400 acres?

Águila: No. Arco Iris Earth Care Project is the name of the nonprofit. Santuario is the name of my home. The resident stewards that care for all of this land live here. This is where the road is open. We have housing, and we have electricity, water, and outhouses that are composting toilets. We’ve really moved up over the years.

RN: You got that road fixed, the road with all the ruts and trees in it.

Águila: Yes. It took me two years to save up the money to fix that road. That was my first combat with Diana. When she let us squat here, with no rights, she said, “I’ll fix that road for you.” When we asked for the land to be given to us, she said, “Okay.” But really, she didn’t want to give us the 120 acres. The Sassafras collective did. She was outvoted. And she reneged on the road. It took me two years, my girlfriend and me, two years to save up the money to open the road. Even then, it was many, many years of partial access. Now, it’s accessible year-round. It took years of maintenance and repairs. During the wet season, it would get really, really impassible.

RN: You know, so many women’s lands eventually fail because it’s so hard. There are a lot of transients among Landykes. You’re the one who stayed, and it seems to be because of the spiritual connection you have, the vision, your dreams. Tell us a little about the dreams that led you there.

Águila: The dream that I had must have been when I was about nineteen, something like that. I started having this dream. I was standing on a mountain. My daughter was a baby. I was living in the ghetto in Dallas, dealing with a lot of stuff. Let’s put it that way. There was a lot of violence around me, and I started having this dream, a recurring dream, which is unusual for me. I rarely would have dreams. But this was more than a dream. It was something that was really calling me.

I was standing on top of this mountain. I was looking down into a valley where I could see a city, a town. There were sirens and fires and explosions. I could hear people screaming, and there was just a lot of violence happening. I was standing there, just looking down into that, and I felt calm. I felt at peace. I kept having that dream. Every time I would have that dream, I would be able to look further into the dream, into the specifics of the dream. Finally, at one point, I saw what I thought was a snake. It looked like the snake was coming towards me from the city, a huge snake.

Many years later, many, many years later, I realized that that was not a snake. That was people walking towards me to that safe place where I stood. It took me years of praying and having that recurring dream. I even had it when I got here. It kept me going for two years. It took me about two years to get enough money to leave Dallas.

We were working class, very poor, kind of living from paycheck to paycheck. And we had a baby. By the time we left [my husband and I], my baby was two and a half. It took me a while to get that money together and get the truck ready to go, rock and roll, and get the hell out of Dodge. I was more than ready.

I met some people in Austin when I was there visiting. I used to hitchhike to Austin all the time to get away from Dallas. Austin was a really better scene. There were a lot of people that I could relate to, that had a different vision, a vision of getting more back to the basics and back to nature. That’s where they told me about this place named Sassafras.

I got really sick one night when I was sleeping on Guadalupe Street in Austin. The street people would hang out there. I was there, and this white couple would bring sandwiches to the street people who didn’t have anywhere to be, who were homeless. I was just there for the weekend, for a few days, and then I’d go back to Dallas to my home. While I was in Austin, I would just take whatever I had on my back. I’d just take a few things: a blanket, a little bit of food, whatever. These people would give us sandwiches.

I got really sick because it started raining, and they took me in. They said, “You need to get off the street. Come to our house.” So they started talking about their dream to move to Sassafras. It was a young hippie couple, and they said, “You should come there!” Sassafras started there. They said it’s a mountain, and I immediately felt the draw. They said, “You don’t have to have any money. You can come to live there for free.” I said, “Ah. That sounds doable. If I can just get there now.” It started that way.

RN: That dream, or at least that connection to the mountain, stayed with you through many things.

Águila: They had said, “Go to Fayetteville. Get a job at the co-op if you can. There was a little bitty tiny store. I couldn’t get a job there, so I got a job at Summer Corn, which was attached to it. That was a little health food restaurant that was also a café and bakery, and I got a job there. They were paying us something like $1.25 an hour, and you could eat for free there. The Austin people finally showed up about a year later, and I had been waiting for them to show up. They showed up, and they brought me out here. When I got onto the mountain, I recognized it. I felt it in my heart, in my being, that I had arrived.

When I got onto the mountain, I recognized it.

I felt it in my heart, in my being, that I had arrived.

RN: And that has kept you there all these many years.

Águila: All these years, yes.

RN: I think it will be 50 years in 2026.

Águila: Yes, it will, pretty soon.

RN: You were laughing earlier, before we started the recording, about my question about whether the land has always been a sanctuary for you. [laughter again from MCM] Talk about that again, and about the neighbors.

Águila: We came here, Jenny and I, or I dragged her here, my little girl, and I didn’t have anything. There was nothing here on the land. Not any shelters. Not a road. Not a thing. Then we had to go by the trolls, which was a Baptist Church at the bottom of the road. They would stare at us, shutting their door. They acted as if we had some disease. I think back on that as an adult. These were adults there. I was a young person, skinny like a rail, because I’d been sick. I had always been thin. Now I was with this tiny, cute little girl. That they would be like that, that they would shut their doors to avoid us, watching us through their windows. It was just… I think, how close-minded they were. You know?

RN: Are they still like that?

Águila: No! No!

RN: That’s good.

Águila: The preachers come and go. They want a certain kind of preacher, it seems. What’s happened is that the young people that were children are now the adults. Now, they’re the big people. They’re starting to run the show more and more. I started becoming friends with some of the elders after their elders passed, ones that were very, super racist. When their parents died, they became less inhibited. They could show some compassion.

The lady at the post office was one of the elders that lived down there. She was the postmistress. She had to talk to me because that’s where I would get all my mail. She was in a little closed-in, tiny building, like the tiny houses they sell now. They were using it as an office. That was the post office at Ponca. She had that privacy. Nobody was watching her. I think she began to realize that I was just a young person with a little girl.

The people at the church were demonizing us queer people of color, calling us devil worshipers. They said every kind of horrible thing about us. When they would get me in a little space like that post office, they felt safe that they could actually just relate to me as a human being. The postmistress has passed on now. I loved her to the end. But all of those people at one time could have been part of a mob that killed us, and we would have just disappeared. The sheriff was horrible. Everybody was like that.

One by one, they either died or they began to change. I never tried to do anything to them. I was living my life. Also, mountain people have a thing about people coming and going all the time. City people would come, and then they would go. I could understand. Why would they want to make relationships with them? Most of them [the transient city people] were getting high and drinking and doing drugs. I could understand that feeling against them. But I wasn’t like that. The neighbors began to see that I wasn’t. Over the years, they began to come to see me as a healer because I had my clinic. They had respect for me because I stayed. I endured. Their parents taught them that this life is hard, and we have to work hard. A lot of those kids just wanted to hang out and not stick around.

RN: Before I started the recording, you said that your drug days were long ago. That was when you were on the street. You aren’t involved in them. In fact, you’re smoking an herbal cigarette that you rolled yourself.

Águila: When I don’t want to roll my own, I just use Isis’s pipe. She was a Black woman that lived here, [an old friend] and she died a couple of years ago.

RN: Your memoir includes a whole section about her dying, and a pictorial essay about Isis’s dying.

[Note: Her full name is Isis Sheila Brown.]

Águila: She wanted that. I don’t know why. I didn’t ask her. We only knew that she was dying about three or four weeks before she died. We had started taking care of her because she needed care at that point. When we got the diagnosis that she was terminal, that very day, she said to me, “I want you to document my death. Document me!”

And I did. I took pictures of her there that day, to calm her down because she was really rowdy. She had brain tumors, and she would get really rowdy. She could be really rowdy anyway. We had been friends for forty years. She said, “I want you to take care of everything.” She told the other women that helped take care of her, “Whatever Águila says, goes. Whatever she says, that’s what we’re doing.” They told her that she might not be able to be making her own decisions after a while. This is Isis’s pipe [gesturing to the pipe in her hand].

RN: I’m sure Isis’s decision had something to do with her spirituality.

Águila: Yes! Yes, absolutely.

RN: Your book is imbued with that spirituality. It begins with a prayer, a Prayer for Águila, by Norma Elia Cant. Is that a friend?

Águila: She’s an elder. She’s an activist and a professor in San Antonio.

RN: The chapters of your book often end with a native word that means “thank you,” and I can’t pronounce it.

Águila: Tlatzokamati. [Both say it. Roughly: Tlat-so-kah-mah-tee.] That’s it.

RN: There’s a strong sense of gratitude and appreciation that goes all the way through your book. Your birth family was poor, you had all kind of hardships, you wound up in foster care, and on the streets, and all that. And still there’s a spiritual component that underlies it. I’m not sure how you did that. It must have been hard.

Águila: My great-grandmother on my mother’s side, Ama Angelita, was my matriarch. She was very spiritual. When she got too old to pick cotton or whatever they were doing, she would sing and play the guitar while the others were working in the fields. She would play for them, cook for them, make food for them on an open fire. My father said that was not his grandmother but he loved her. He said she was a light, like a saint, like an angel. No matter how poor they were, she was always generous. Somebody would come who didn’t have any food, and they would offer whatever they were eating around the fire, and she would be singing. She would prepare food for everyone while the other workers were in the fields, ellos estaban cosechando. That’s what they called it. They picked and gathered, whatever they were gathering at the time. She would always be giving.

I saw my great-grandmother die. I must have been smaller than Jenny. I think I was four. She was in her bed, and everybody had gotten around her to be with her. She had this tiny little house. I remember it had a tiny picket fence around it, a little white picket fence. It was a little… a shack, a really tiny, little wooden house. All these people were just flooding all over the yard, in the house, and out into the street, there to witness her passing, to be with her.

We came from Dallas, and we were the last ones to arrive. I remember hearing somebody saying, “Maria and Jose and the children are here” (in Spanish) “They’ve arrived!” She had been waiting for us. My mom and dad brought us in next to the bed, and I was standing at eye level as a little child at her face, right there by her face. She’s in a little cot. I looked at her, and she looked at me, and I felt something come into me. She smiled when everybody had gathered, all her children, great-grandchildren, all had gathered around her. She was ready to say goodbye. She just smiled and closed her eyes.

She looked at me very clearly. I remember that. And I really feel like she passed that down to me. My mother was also a vidente [a seer], so she had that spiritual background. My mother was a seer of the future. She never would talk about it because what she saw were always terrible things that were coming: tragedies, someone died, someone got hurt, somebody was going to get sick, or whatever. She just decided that she wasn’t going to do that for everyone. She was just going to do that for her family. She never told anyone except me. That was my mom.

RN: The matrilineal, the spiritual.

Águila: That’s the word I was looking for, matrilineal.

RN: It’s not just spirituality, it’s also a gift that different people have recognized in you, like your teachers, and the one that made you “Águila.”

Águila: Yes, yes. The eagle feather is given as a show of… it’s like when you go from being a soldier to a captain or a sergeant, captain, general. When you’re little, you can be given little feathers for a good deed. As you get older and you do good deeds that are recognized by the medicine people, they give you an eagle feather, a full-grown eagle feather. I had so many of them. My teacher gave me a headdress to put all my eagle feathers in. She gave me the headdress. I would bring my eagle feathers in a bundle when I would go to see her, my medicine bundle. She said, “It’s time for you to be a full eagle.” I had gathered enough eagle feathers. Those eagle feathers were given to me by the eagle itself sometimes. An eagle would drop an eagle feather, I would gather that. I think I probably got one or two that way. Maybe I found one under an eagle’s nest, and one fell.

RN: Our project is about lesbian-feminist activism in the South, about what lesbians did in Southern states to improve the world where we live. Your memoir describes many ways that you have resisted racism and bigotry around you. You have taken steps to create a sanctuary for women and children facing the kind of hardships you faced as a child and as a young woman. What would you like readers to take from your story, and how might they put lessons from your story into their own activism?

Águila: I want people to have empathy and compassion instead of judging so quickly. That’s what people do. They judge and separate. I told my story [in the memoir], and that was very hard. I’m still recovering from having to retrace that. It took us almost five years to get it to publication. It took a lot of energy from both of us. Lauri has gone through major changes from that work we did together. She is an activist and everything, always had been, and she has her own story. She’s a Jewish woman. All of that triggered both of us. Recounting, rehashing that. She would really try to get as much out of me as we could get, but we would have to take breaks. Even when she would travel all this way, we would have to take a break. Maybe we’d work on it in the morning, and we’d take a break, take a walk, and do some other things to be able to continue.

I want people to have a paradigm shift if they can somehow identify with any of those things in their own life. I feel like that there must be something that you can identify with to give you that empathy, to make the shift to seeing that we are all children of the Earth and stars. We are all children of the Universe, no matter how old or how young we are. We all deserve love and respect; deserve to determine our life without being judged and oppressed, or worse, genocide. People need to really take it in, really understand how that could have been themselves.

This did happen to me. In spite of all that, in spite of all that shit, I did not give up on people. I never gave up on people.

As long as I’m breathing and speaking, I’m going to try to teach people

to be more understanding, compassionate, loving, supportive

I believe that we are born of love, a seed of love, of light. Of light that is love. We’re just going through our process of learning how to walk in this spiritual way, remembering many things that we’ve forgotten that’s in our DNA, that’s in everyone’s DNA. They can try to obliterate it, but it can never be erased. It’s in our blood. It’s in the air that we breathe to live. It’s in the water. When they can combine that together to remember that all these things are part of us, the elements, the water, the air, the earth, the plants, the animals; that we’re all connected. Let’s respect each other.

I’m a hunter. I hunt and I take life. I kill a chicken and eat it; but with much respect. When I teach these young people about killing a chicken, I do a prayer for that chicken. I tell them, “If you all will just do that one thing when I die, thank them for my spirit and for everything that I gave, the way this chicken is going to give us, so that we can sustain ourselves, I will be happy. My spirit will be happy and proud of you that you’re doing that. It’s just respect and love.”

Right now there’s so much controversy about so many things, about these wars that are going on, and all these killings. I see people being divided by that. Yes, it’s a terrible thing. It is a terrible thing that’s happening. It’s also leaking our energy. I cannot get sad enough to bring back one of those children that was killed. It will only weaken me and my work that I need to do.

That is their path, and I’m sad that they’ve chosen that path. All those that are assisting in that path of genocide, destroying the Earth, and destroying beautiful people, and beautiful things that they have created. I try not to even go there. I send out a prayer, and I just get back to my work. That’s all I can do because I cannot allow it to crush me. Then I will be letting that take over.

As long as I’m breathing and speaking, I’m going to try to teach people to be more understanding, compassionate, loving, supportive, and those kinds of things. That’s what’s important. Not everything else. Everything else is materialistic. Yes! If you have more, give more. That’s what’s considered honorable in our tradition. When you get to a certain level of having so much, it is time to do a giveaway. You take your things out and you have a giveaway. You give away a lot of your stuff. When you get into this place of inequities, such severe inequities… but that’s not what some people are doing. It’s causing a lot of pain and hurt in the world.

RN: I think your book goes a long way toward sending love in that direction. And faith and hope. I felt that it was spiritually inspiring to see what you had done with your life, what you’d overcome, and where you are now.

Águila: Yes, I think knowing that, knowing that life is not easy. I don’t want them to think it’s all soft, gratifying, constant self-gratification. They can actually do something that’s honorable, something that’s a legacy that will help the next seven generations survive.

We played Wahoo the other night with my daughter and my daughter-in-law. My daughter is a lesbian, too. They just got married after seventeen years together, and they finally got legally married. We played games, and we were being ruthless with each other. I said, “But this is a game. This is just for fun to tease each other so that we’re not so wimpy.” [Laughter] If it does that, that’s my intention. My intention was not to make people sad and discouraged, but to encourage them with “if I can do it, you can do it.”

RN: Yes, rise from the dead, for one thing. The last word in the book is Tlatzokamati. I want to end the interview with that.

Águila: Well, thank you, Rose. And thank you for all the good work that you do. I pray that you have a blessed life!

RN: Tlatzokamati.

See also:

Águila, “Arco Iris, Rainbow Land: The Vision of Maria Cristina Moroles,” Sinister Wisdom 98 (2015): 43-52.

Maria Cristina Moroles (Águila): Building Sacred Community on the Land, interview by Rose Norman, October 27, 2014.

Rose Norman, review of Águila: The Vision, Life, Death & Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains (University of Arkansas Press, 2024).