Sandra Gail Lambert: Becoming A Writer

Interview by Rose Norman at Sandra Gail Lambert’s home in Gainesville, Florida, on March 21, 2016

Personal Background

I grew up as a military brat, which is placeless but has a very strong culture. This, I think, shaped my life, especially within the lesbian-feminist community. I mean, my father was an actual, not metaphorical, drill sergeant, so I grew up with a sense of discipline, for better and for worse. My mother was an English war bride who survived the London Blitz. My father was from West Virginia, though he had run away from home at fourteen during the Great Depression and had never really returned.

We never lived or were stationed in the South while he was in the service. When my father retired from the Air Force, we settled in Roswell, Georgia, which is now a suburb of Atlanta but was then a country town. It was an adjustment; not long before I’d been living in Oslo, Norway. I was in the Atlanta area from the middle of my junior year until I moved to Gainesville, Florida.

I got a scholarship to Emory; it took me about eight years to graduate from college. Those were my lost years: a lot of drinking, a lot of trying to figure out my sexuality. I transferred from Emory to Georgia State University, then ended up at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, Georgia, where I came out a Physician Assistant and a lesbian in 1978.

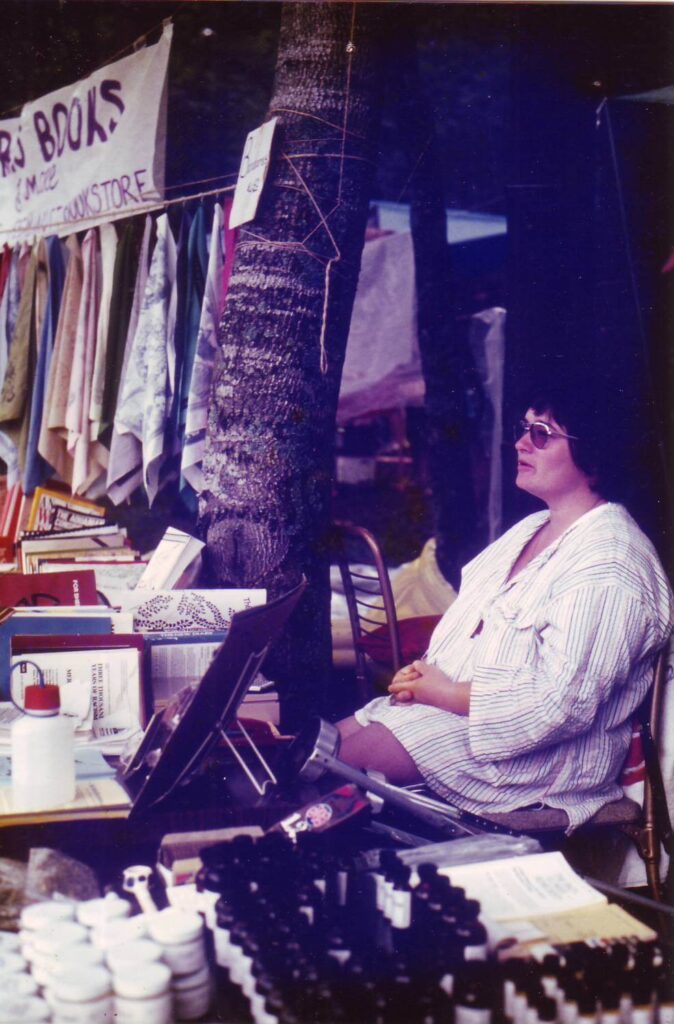

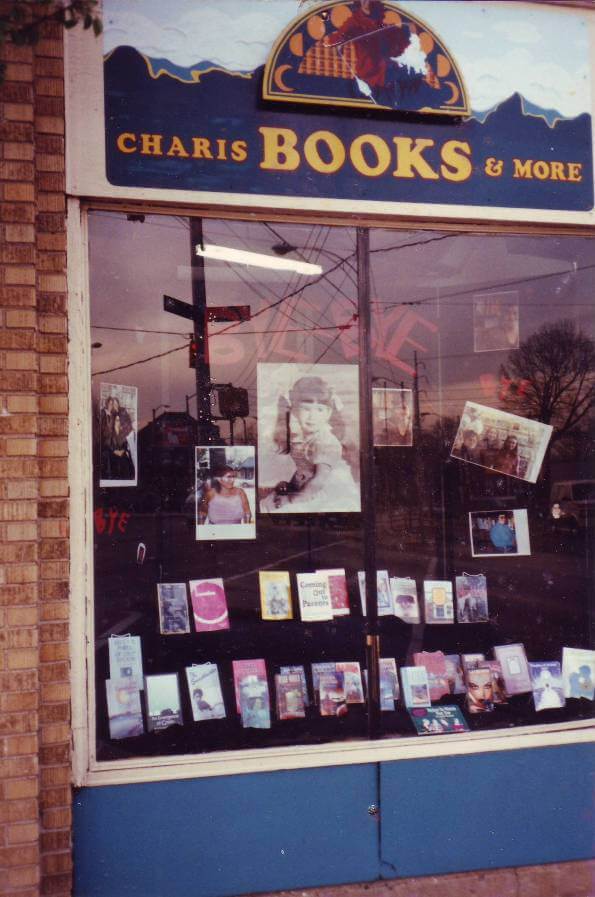

While working in Atlanta, I began volunteering at Charis Books and More and by 1980 or 1981 had become what would soon be defined as a “worker-owner” of this feminist bookstore, which is still in operation today (in 2023). I worked full-time there with two other worker-owners (including the store’s founder Linda Bryant) until 1988, when post-polio syndrome forced me to take Social Security Disability Insurance and stop working. I moved to Gainesville, Florida, where I began to focus on my writing.

Biographical Note:

Sandra Gail Lambert throughout her life has been involved in many kinds of activism, including disability rights actions, antinuclear protests, and peace activism in South Carolina and Florida; and antiracism work through the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA).

While working in Atlanta, Georgia, she began volunteering at Charis Books and More, the feminist bookstore. By about 1980, she became what would soon be defined as a “worker-owner” of Charis Books and More, which is still in operation in 2023. She worked full-time there until 1988 with two other worker-owners, including the bookstore’s founder Linda Bryant. She credits becoming a writer to this immersion in the vibrant world of lesbian-feminist publishing.

(Read full bio.)

Finding Home

My roommate in Augusta was a lesbian. She, her girlfriend, and I drove many miles through back roads to a trailer in the middle of a pine forest where two lesbians that they knew lived. They put these two albums on the turntable—Cris Williamson’s Changer and the Changed and Meg Christian’s I Know You Know. I felt as if I had found home. I finally graduated, found a job back in Atlanta, and discovered I hated working as a Physician Assistant. Thankfully, though, I found the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance and Charis Books and More.

Becoming a Feminist

How did I become a feminist? I have to think back to my very first feminist outrage moment. I had polio as a child, so I have shorter-than-typical legs, which means pants and skirts were always too long. My mother quickly turned the job of hemming over to me. I, like my mother, hated sewing, but I had to hem almost every dang piece of clothing I wore. One day when I was a teenager, I was shopping at some department store [in Atlanta], maybe Rich’s. When I bought pants, I saw a sign saying they hemmed pants for free. I was ecstatic! I went over, and they said, “Oh, no, we just do that for men.” It turns out, they’d been doing it for men all my life! It outraged me. This feeling just swept up on me: how come men get their pants hemmed for free, and I have to do this onerous job? It was just one of many moments; for instance, the first time I looked for a job, they [the classified ads] were divided by men and women. That outraged me as well.

Growing up disabled, being on the outside, I didn’t have disability rights consciousness, and I didn’t know the word lesbian, or any of those words, but I knew I was separate in that way, too. All that led me to notice and be bothered by social inequities, although I wouldn’t have had any of those terms to express it. I didn’t have the name for lesbian, but I didn’t understand all the boy-girl stuff. I didn’t understand the motivations, what the transactions meant. I would try to mimic it, but I’d make mistakes all the time, because I didn’t have any of the underpinnings required to negotiate that social world.

Working for Charis Books and More (1980/81-1989)

I was involved with the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA), and was part of the “Boogie Women” committee that planned social events and also helped organize anti-racist groups. There we all were at ALFA, cutting our political teeth and our sexual teeth, clad (and unclad) in our ubiquitous flannel. During that time, I volunteered at Charis Books and More, the feminist bookstore in Atlanta, and I loved that. I loved books. Reading had saved my life over and over again. I was one of those people who would call in sick to work so I could finish a novel.

Charis had a job opening, but I didn’t apply because I thought I wasn’t in any way qualified for that job. Then another volunteer applied and got it. I knew, coming from a military background with a pretty high work ethic, that I was much more focused and better at what I was doing than this person. I told myself then that if another job or any opportunity came up, I was going to leap for it. “I’m just going to jump. I’m going to do it!” When the volunteer who got the job soon flaked out (we were all figuring out our lives, and she moved on to the next thing to figure out), I said, “I want this job,” and I got it. I think that was 1980 or 1981. That’s how I ended up at Charis.

Though I still owed money for my school, I quit my job as a Physician Assistant anyway, and started working full-time at Charis. It was so exciting to be around books all the time and do work like that. I knew nothing about business. I had to learn basic concepts like “cost of goods sold” and “fixed expenses” and “net vs. gross.” In the military, it’s “get the mission done.” I had always been able to focus in that way, getting things done the best I knew how. I made tons of mistakes, but I had that daily attention to detail that’s needed in a small business, which was both helpful and at times annoying.Before and during my time at Charis, I continued my involvement with the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance. I was also part of the Savannah River Plant civil disobedience action—an anti-nuke group. I volunteered, in a small way, for the Black Woman’s Health Project conference and was one of the organizers of the first LEAP (Lesbians for Empowerment, Action, and Politics), a weekend retreat held outside of Gainesville, Florida, in 1984 and 1985.

I took karate with Mariana [Kaufman] and helped with self-defense courses for women. You had to be really careful. You weren’t allowed to say, “Beat the crap out of them. Make sure they don’t get up.” She could have gotten in a lot of trouble teaching anything like that. You had to teach what I thought was just useless: “make them go down, and then run.” For me, using braces and crutches, that was stupid. So, Mariana would take me aside and say, “just make sure they don’t get up.” Even to rent a place [to teach in], she had to make a lot of assurances that she wasn’t teaching that level of what was called “aggression.”

Books and So Much More

The more I worked at Charis, the more my activism was involved with the work we did at Charis. We changed people’s lives constantly, daily. Early one morning before the store opened, I came out from the back office to check inventory on something. Two very young women were at the front door with their faces pressed to the glass and their hands blocking the shadows to see in.

These two women had just found themselves together. They lived in South Carolina (or somewhere in the South), and had heard about Charis, that there were lesbians and lesbian books here, and that maybe they could find out something about this thing that had happened to them. They drove through the night to [get to] us. I let them in and showed them a few books and magazines and notices about support groups, then watched them wander the shelves in a daze. I went back to the office, but I know that [experience] changed their lives. Not that they weren’t changing their lives just fine on their own, but we could help with that.

When books about incest started being published—not textbooks or professional books about incest or domestic violence, but books for real people—we carried all of those books. At Charis, we were sometimes ahead of our customers and sometimes our customers led us to places. In this case, we diligently searched out books on incest.

Women would come in and say their therapist had recommended a book. They had been to another bookstore, and the clerk there had laughed at them when they told them the title they wanted. At our bookstore they didn’t have to say anything; we’d have the titles there. They could just wander around and find them. Of course, they’d have to reveal themselves in order to bring it to the register, sometimes for the first time. They weren’t telling us outright, but someone now knew what had happened in their life. We had a code [an ethical code].

We never told anyone else who bought books in this area [incest]. That was sacrosanct, at least for me, and I think for everyone else. It didn’t matter what type of book it was. Later on, when lesbians started figuring out how to purposely have children, there were books about that. We didn’t spread that around either. We were careful. We sold coming-out books, especially around the holidays, because they were going to go home to their families, and this time, they were going to do it; they were going to come out. So, we would sell them these coming-out books and give them lots of encouragement.Things like that happened routinely. It was very exciting.

I eventually became an owner at Charis. It was me and Kay Hagan and Linda Bryant working there. [Kay Hagan left in 1984 or 85, and Sherry Emory became the third worker-owner.] It had always been a pretty amorphous structure, with Linda as owner. Kay pushed to have the structure written down. After a lot of meetings, we came up with [the idea for] a for-profit, worker-owned business, workers being the three of us. We set it up so that you didn’t have to buy in or get paid if you had to leave. You wouldn’t have to have a lot of money to come in. I don’t know what happened about that after I left, but that’s how we structured it.

Bookselling as Political Activism

I think that a main political work that all of us did during that time was to come out. You can trace this whole change in society, especially the acceptance of same-sex marriage, to the fact that a batch of us came out and not just in some segments [of our lives] and not others. We were out. Some of us lost jobs, some lost their children, some of us got beat up by family members, but we were out.

We did a lot of political action through our windows.

We just took out extra plate glass insurance.

At the store we had three big, glass-paned windows that anyone could throw a rock through, and we put the word lesbian in them. They looked out over Little Five Points, meaning five streets coming together. We did a lot of political action through our windows. We just took out extra plate glass insurance. That did not mean that everyone who worked there was a lesbian, but we were very out as a store. We did a lot of other good stuff, too, but that one, not-so-simple thing often gets overlooked.

Transitions

At the end of my time there, I began to experience something called post-polio syndrome, which we didn’t know much about then. It happens maybe thirty years after someone has polio. All the mechanical muscular coping mechanisms begin to give out. They’ve been used too long and too hard. You have increased weakness, a lot of pain, and terrible exhaustion.

At first, I didn’t know what it was. The way it manifested was my starting to make a lot of mistakes. I took great pride in not making mistakes. I was the one who had my lists, and so on. When I started making mistakes, it really freaked me out. Here I was in a lot of pain and exhausted. I didn’t have much patience for anything. There were all the signs of burnout and exhaustion. The store wasn’t that much busier, but I was less capable of doing it [the work]. There were also interpersonal dynamics that didn’t help. I would go to post-polio groups and figure out more and more about it. I’d try to pace myself.

That whole end-time was not easy with all of that going on for me. I’m just trying to figure out how to get food to eat, I’m making terrible mistakes, and I have no patience. The beginning of that was difficult for all of us. It was me, Linda Bryant, and Sherry Emory. Sherry and I were ex-lovers, so there was that dynamic as well. But by the very end, we were our best selves, and I’m really proud of how that all ended. We pulled through. At other stores, there were locks changed; you hear terrible stories. But we each tried our best and just decided to let certain things go.

I was very involved with some lesbian land, Pteradyktil [about two hours southeast of Atlanta, near Swainsboro, Georgia. See story in Sinister Wisdom volume 98]. I’d been part of creating and maintaining that [community]. I’d been on the Peace Walk, by this time, so I had a big group of friends here in Gainesville, [Florida]. from the Peace Walk. They all got together and gave me a big canvas tent one year for my birthday. An ex-lover of mine, Margaret, lived on that land. She built a ramped platform, so I had a tent with a bed in it. Instead of figuring out how I could work less than my regular 70 hours a week, I would take a week off every month and go live on the land and rest. This was my attempt to keep working at the store. But it just kept being more and more untenable. There was a small hill up to the store. When I found myself part way up, leaning into the brick walls, unable to take another step, I started using a wheelchair. That helped for a while, but it became harder and harder.

Eventually, I applied for and got Social Security Disability Insurance, which meant I had to stop working. That’s when I moved down here to Gainesville, where I’d become part of the lesbian community from the Peace Walk, as well as by being one of the organizers of the first LEAP.

Womonwrites and Lesbian Readers Potluck

I started going to Womonwrites [a lesbian writers conference in Georgia] in the early 1980s as a bookseller for Charis. I didn’t think of myself as a writer, but was surrounded by writing. Even after I left Charis and moved here to Gainesville, I would go to Womonwrites most years until issues around disability access kept me from returning. When I went, though, it was a place where I learned to become a decent reader of my work. You really learn when you’re reading out loud to a group of people. You can feel really ashamed if your writing isn’t perfect.

Something that began in Gainesville the year before I moved here was the Lesbian Readers Potluck, which still goes on today. [See below for a Sinister Wisdom story about the Gainesville Lesbian Readers Potluck.] We would read our writings to each other. That’s it. There wasn’t any critique allowed. No specific feedback was offered. Sometimes it was a place where a woman read us the first thing she’d ever written. Sometimes accomplished writers with many publications read. But what it meant for me was that no matter what I was writing, once a month I had somewhere to read out loud. Quite often, I was filled with shame, because the piece wasn’t good yet, but I kept using the opportunity to present my work. Eventually, I needed more than that, more critical response from people who wrote a lot better than me. That’s when I went searching for writing workshops and retreats.

Being a Writer

All my life I was a huge reader. I was the little girl with her math book open and the Nancy Drew book inside (which explains my shaky long division skills). I was a pretty rigid person; I had that military upbringing. I never thought of myself as creative in any way. Even at the bookstore, I thought my job was to make the space available for all our amazing writers. I had authors come [to do a reading]. I made sure to order their books, put them on the front shelves, talk them up. I always felt my responsibility wasn’t so much to the person who was coming as to the customers that would come attend the program. They had to know that we would always present a decent event.I ran the business in a way that meant it could stay open and we could keep doing our part. I thought this was my calling.

In the meantime, I had to write for the store, and I found myself enjoying it. We had a holiday catalog, so we needed to write blurbs—you know, sixty words that would accurately describe the book, but would also be exciting enough that someone would pay for the book. That teaches you a lot. When we started to do weekly programs, I wrote all the flyers, which involved interviewing people about what they would be doing, then writing it up.

Then my body started changing from the post-polio, and in the late 80s I started to write in a more creative sense. I was surrounded by writers. Lesbians wrote all the time about anything and everything! During that time, there was more of an emphasis on the story, what the experience was, rather than the craft of writing. That was an extremely welcoming and safe place to start writing. You didn’t have to write well; you just needed to write honestly about your life. I started being published in places like Common Lives, Lesbian Lives and Sinister Wisdom.

Writing from Gainesville

When I moved to Gainesville, my life completely changed. I went from being a big cheese at a big feminist bookstore to not having a job for the first time in my life, which was disorienting. My political activities were curtailed by ongoing exhaustion and pain. I did do a stint helping to put out at the local lesbian newsletter and managed to attend and be jailed at a civil disobedience protest down in Orlando. It was for a disability rights group, ADAPT (American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today).

I started to write more seriously. There was a long gap when I didn’t publish anything; I was trying to learn how to write. I wanted what was in my head to work on the page. I was living on very little money, so I couldn’t go to a Masters of Fine Arts (MFA) program (even though I didn’t know what one of those was), much less classes or anything like that. I would read, and I would stalk any writer who came to Gainesville and gave a reading somewhere. I didn’t know what to ask them. I didn’t know the right questions, so I would be that person who asked “what time of day do you write?” I didn’t really care about the readings part of it. I wanted them to talk about the process.

As a result, I was writing more and more. I was in lesbian writing groups, which had been helpful for many years, but were now becoming unsatisfactory in making my writing better. They had a more relaxed structure than I was wanting. Then I realized there were these retreats, and some of them were free, though I couldn’t drive very far.

Out of My Bubble

I applied to Atlantic Center for the Arts, which was a really fancy retreat center for writers. They had a three-week retreat that was close by. I was rejected and rejected, and then I got on the waiting list, and finally ended up being accepted. That was my first experience out of my bubble. People didn’t know me at all. I had the highest to the lowest emotions in one day, from exaltation to despair. I learned more about my type of writing. I hadn’t even known how to describe it. It turned out I wrote more literary fiction than anything else. I met people who sent their work out to literary journals, which I knew nothing about. I got a list of names from them and I started to do that.

I completed a novel. I had no success in getting published, but I finished it. I started writing both fiction and personal essays, getting pieces accepted in different journals. I really thought of myself as a fiction writer, but I was getting more personal essays published, so I started writing more of them. I would use one success to build on another. Then I decided to use some of my savings to go to workshops where you pay to go. I went to one with Connie May Fowler, which pushed me to a new level of seriousness about my writing. I went to places where my work was looked at by people much more accomplished than I was. I audited a creative writing class with Suzanne Carlton at Santa Fe College. She worked with me outside of class (as she did with everyone). One of the first pieces I got published in this new era was one that she had helped me with.

One of the things I learned to ask at these workshops was, “What is the next thing I need to do to make my writing better?” I would get answers that went from “your dialogue sucks” (they wouldn’t use the word sucks but pretty close) “and this is how you can improve it,” to “you don’t reveal emotion enough. Don’t stop, write the next sentence.” It went from very specific to more theoretical. My goal at all of these [workshops], having been a good lesbian feminist community organizer, was to gather other writers to me. They didn’t have to write in the same genre or anything. You feel a sense of equal seriousness about your writing with someone else. An equal focus. Slowly, I began to “write better.”

Hope is great, but eventually hope can keep you from moving forward.

I started getting accepted by fancy-ass literary journals. By this time, I knew more about things like that. I eventually pulled apart the first novel, which was a thinly disguised autobiography (as many first novels are) into short stories and personal essays. I wrote a second novel, and I knew that one was better, that it was worth something. I submitted to agents and all the small presses that would take manuscripts without agents. I would get close-but-no-cigar rejections, straight out rejections, silence. I did this for years, and I finally gave up. Hope is great, but eventually hope can keep you from moving forward, so I mourned it and put it away in that sense of moving on.

They’re always saying in publishing that you have to have a “platform.” I think what you have to have is community. I learned that from being a lesbian, learned about basic day-to-day survival. I think this knowledge served me well in this writing endeavor.They’re always saying in publishing that you have to have a “platform.” I think what you have to have is community. I learned that from being a lesbian, learned about basic day-to-day survival. I think this knowledge served me well in this writing endeavor.

Now I have a memoir that pulls together all those essays, many of which have been published. The manuscript is in that stage of getting rejections and close-but-no-cigar and silence. I feel all that despair. You’d think I’d be used to it, but you forget how badly all that felt. I’m working on a new novel. You just have to keep moving forward. I try to use every bit of acknowledgement I get to build for the next piece of acknowledgement.

I understand literary citizenship from growing up in a vibrant lesbian community. I try to give back. Not just reading other people’s work and giving feedback, but also doing book reviews, organizing conferences, supporting other people, connecting people, encouraging people, having lunches where you tell them they are good writers, using social media to support other people.

See also:

Biographical information, http://sandragaillambert.com/

Publications by Sandra Lambert, http://sandragaillambert.com/publications/

Sandra Gail Lambert, “Lunar Eclipse,” Sinister Wisdom 40 (Spring 1990): 72-75.

Sandra Gail Lambert, “Disability and Violence,” Sinister Wisdom 39 (Winter 1989-90): 72.

Sandra Gail Lambert, A Certain Loneliness: A Memoir (University of Nebraska Press, 2018).

Sandra Gail Lambert, The River’s Memory (Twisted Roads Publications,2014).

About Charis Books and More:

Errol “E.R.” Anderson, Blueprint for a Feminist Bookstore Future—A Personal History of Charis,” Sinister Wisdom 116 (Spring 2020): 67-75.

Linda Bryant, “Personal History of Charis.” Charis Books and More website, July 2009.

Saralyn Chesnut, Amanda C. Gable, Elizabeth Anderson, “Atlanta’s Charis Books and More: Histories of a Feminist Space.” Southern Spaces. November 2009.

Saralyn Chesnut and Amanda C. Gable, “ ’Women Ran It’: Charis Books and More and Atlanta’s Lesbian-Feminist Community, 1971-1981,” in Carrying On in the Lesbian and Gay South, ed. John Howard (New York: New York University Press, 1997), pp. 241-284.

Other Topics

Judy McVey, “Pteradyktil: Lesbian Land and Change,” Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 101-105.

Woody Blue, “Gainesville Lesbian Readers Potluck,” Sinister Wisdom 116 (Spring 2020): 99-101.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.