Jade River: Mother’s Brew, Where Feminist Consciousness Grew

Edited for the web by Salkana Schindler. Phone interview by Rose Norman on November 12, 2015.

Mother’s Brew bar, managed by Jade River, was a lesbian-feminist cultural center for the Louisville, Kentucky region, and a safe space for lesbians.

In Jade’s words:

In 1975, I was married to a rich man, I had a two-year-old son, and I was unhappy, trying to figure out where the grown-up Girl Scouts had gone. A friend of mine from Girl Scout camp came to visit, and she told me that she is a lesbian. Then she told me she loved me, asking me to leave with her. I left ten days later. That was my introduction to lesbians.

Next, I hired an attorney to get a divorce (from the man I had married), and the attorney turned out to be a lesbian. She gave me an Alex Dobkin album and asked me if I wanted to go to a meeting of the Lesbian Feminist Union. At that point, I wanted to go anywhere there were lesbians.

The Lesbian Feminist Union formed when Louisville’s Lesbian Task Force of NOW had split off from NOW. At one of the first LFU meetings, women from that task force had been asked not to identify themselves as lesbians in things that were being included in materials for legislative actions. NOW was afraid that if they sent something with the word lesbian in it, NOW would be discounted. I believe that was the beginning of the end of what happened with the lesbians in NOW.

At our first Lesbian Feminist Union meeting, my partner and I took positions on the board and committees even though we didn’t really know anything about feminism. We figured that we could learn quickly, and we did. Interestingly, we were the only butch-femme couple in the Lesbian Feminist Union. Regardless of that, we were pretty sure that we believed in a feminist belief structure, and we were very interested in working to promote lesbian feminism.

Most of the women in the Lesbian Feminist Union followed a band called River City Wimmin. Before Mother’s Brew, River City Wimmin would play not at queer or gay bars, but at local, straight bars. That’s where there would be problems, where [straight] men were asking women to dance, and the women would decline. That led to women getting in a lot of fights. We had some battles that we gave names like “the Midtown Skirmish” and “the Sugarbaby Express.” We actually gave out medals to women who participated. The medals were for things like Valor, Bravery, and Best Bluff. I was really concerned that women were being accosted and having to defend themselves, and that someone might get seriously hurt.

Biographical note

Jade River was born July 2, 1950, and passed into the eternal arms of the Goddess on July 20, 2020. Jade River cofounded the Re-formed Congregation of The Goddess—International (RCG-I). RCG-I is one of the first, legally incorporated, tax-exempt religions serving the women’s spiritual community. Jade also created the Women’s Thealogical Institute (WTI), the first national organization to offer in-depth, multidimensional training for women seeking education in Goddess religion and woman-centered spirituality. For some students, WTI culminates in ordination as priestesses. Jade River is the author of several books.

Mother’s Brew and the Lesbian Feminist Union

Jade River was one of approximately fifteen lesbians in Louisville, Kentucky, who formed a corporation to start Mother’s Brew bar. Mother’s Brew was a lesbian bar at 204 W. Market St., where the Louisville Convention Center now stands. Jade formed the corporation, and she managed the bar for the first few years.

The Lesbian Feminist Union (LFU) made its home at Mother’s Brew until LFU moved to a larger space. Because most of the shareholders of Mother’s Brew were also members of LFU, and because they were headquartered in a room at Mother’s Brew, the bar became a central organizing place for lesbian-feminist activism in Louisville until it closed circa 1979. Mother’s Brew closed after their house band, River City Wimmin, broke up. In this interview, Jade River tells her story of how all that happened.

At that time there was only one gay bar in Louisville, a men’s drag bar. Even to go there wasn’t safe because queer bashing happened right outside the door. There didn’t seem to be anywhere safe for women and lesbians to go.

My family owned three corporations in Louisville, and as a result, I had some business experience. A group of women from the Lesbian Feminist Union, plus some community members who followed River City Wimmin, incorporated and sold stock to open a women’s bar where women could be safe. We named it the Mother’s Brew. We sold shares for $100 to any woman who would buy one. We incorporated as a private women’s club. To come in, you had to be a member. We sold memberships for $1, and we sold them only to women. Men were not eligible for membership.

The bar came with everything: the tables, the chairs, even the glasses.

All we had to do was buy the liquor and build a stage.

Once we had enough money to start, we began looking for a space for the bar. Most people would not rent to us because they suspected that we were opening a queer bar, which was kind of true. We found a second-floor space on Market St. (where the Louisville Convention Center is now) with 23 steps up from the street. I was very naïve not realizing that we were renting from a bookie who was connected to the Mafia. Bookies are common in Louisville because of the racetrack. The Mafia rented to gay people at that time. That was part of their thing. But I didn’t know any of that. The bookie was very nice. We called him Papa Joe and had a very good relationship with him. He’d say, “You girls are good. You keep the place clean, and you don’t have any guys up here causing trouble.” He would bring us treats from his other fronts, like fruit from his fruit stand, or pie from his restaurants.

The bar came with everything: the tables, the chairs, even the glasses. All we had to do was to buy the liquor and to build a stage. It had a disco machine that we boarded up and made a stage over it because we were committed to live music. The owners helped us rent a pool table and pinball machines.

That’s part of how the community started to organize around the bar. The bar had lots of rooms. It had a main bar with a dance floor, a room with a pool table, and another room with pinball machines. It had an art gallery, and one room that became the offices of the Lesbian Feminist Union. You could go there and get a whole cultural experience: hear women’s music, go to an art show, go to a meeting of the Lesbian Feminist Union. It was all there in one space.

When the police were at the door – and we frequently got raided – we’d turn on all the bright lights in the bar, and they would know to go out the secret door to stand on the balcony until the police left. We came and got them when it was all clear. Mother’s Brew was a very safe place for lesbians to be.

One of the interesting things was that, because it had been a Mafia bar, it had things like a speakeasy door with a window to see who was outside, and not open the door if you didn’t want to. Mainly, it was men that we didn’t let in. When you did open that door, it slid, instead of swinging out or in. The bar also had a secret door, a wall panel off the dance floor. You could push it open and walk out onto a balcony in the alley behind the bar; almost no one knew it was there. When people came in the front door, and if there was someone at risk for being known in the community as a lesbian (a local elected official, a teacher, or a minister), we’d show them the secret door. When the police were at the door – and we frequently got raided – we’d turn on all the bright lights in the bar, and they would know to go out the secret door to stand on the balcony until the police left. We came and got them when it was all clear. Mother’s Brew was a very safe place for lesbians to be.

We had some unexpected people who came regularly. A group of nuns came every Friday night when the bar opened at about 7:00 pm at night, and they stayed until 9:45 pm because they had to be back at the convent by 10. We also had hookers who came in because they were protected at our bar if they were being hassled by their pimps. We wouldn’t let the pimps in. (They were men.)

I think it was the Lesbian Feminist Union and, through that, Mother’s Brew bar that made Louisville a lesbian feminist hot spot. After we got the bar, we started doing productions. Shortly after I had come out, I had been fired from my job as director of a day care center when somebody outed me at work. Around that time, we had gotten the space, and we were pretty close to opening the bar. I became the first manager and producer at the bar. River City Wimmin was our house band, and they played most weekends.

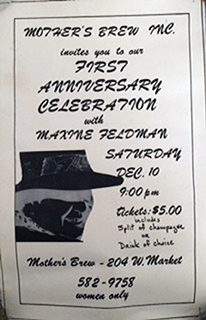

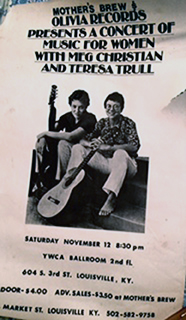

We had a juke box with 45s [recordings on vinyl of single songs, one on each side] of women’s music on it, not many, but we had people like Maxine Feldman and Cris Williamson. That was the year the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival started [1976]. The festival sent us tickets to sell at the bar (although they didn’t do that in later years); and a lot of women who frequented the bar went to the festival. Through that festival, we got to know more about women’s music artists, and we began producing most of the well-known names in women’s music, like Cris Williamson, Maxine Feldman, Meg Christian, Kay Gardner, Holly Near, Teresa Trull, Reel World String Band, Woody Simmons, Margie Adam, and Alix Dobkin. Those are a few of the ones that I can remember. We produced other women’s music artists as well.

We would have somebody about twice a month from the women’s music industry. We developed a network, and we would drive artists to other places where they could also do concerts. We’d drive them to Cincinnati, and someone there would drive them to Columbus (Ohio), and that kind of thing. We formed a kind of circuit of women’s music artists. They’d either go north or south. Frequently Mother’s Brew would be their first stop. We didn’t have much to offer them besides this circuit through the lower Midwest and the South.

Financially, Mother’s Brew did well. We had a regular venue. Women knew that if they went there, there would be something exciting. At first, we drew a local crowd. Over time, we were drawing a regional crowd from the surrounding states. It became a cultural center for the region, not just for Louisville, though it was the Louisville women who did most of the work. River City Wimmin got paid every week (not just the cover charge), and they got drinks for free. If they were playing, people came.

Money was not a problem in the first few years. I left the bar when I got another job, but I think I was there about four years [1975-1979]. Over time, it became more difficult; but the first few years it was open, we were fine. When we did concerts, we normally made money. In the bar, we could seat about 100. If we thought somebody would be a bigger draw, we would rent an outside venue that would seat 1,000. That’s what we did for Meg Christian and Cris Williamson. We wouldn’t fill it, but we would get 600-700 seats filled. We used to explain to Olivia that we were in a depressed market for selling tickets. We could get about $10 per ticket, maybe $12, sometimes, for a big name. But we would compensate for that by driving performers to other venues.

At that time, Mother’s Brew was a real, lesbian-feminist cultural center for the region around Louisville and the surrounding states. When the Lesbian Feminist Union moved into Mother’s Brew, we had lots of committees: a battered women’s initiative; mothers’ issues and day care group; a writer’s group; a newsletter group; a lesbian oppression group. That’s where the spirituality thread I’ve written about started, too [see link here to Jade’s published pieces, “Three Times a Priestess”].

Feminist spirituality was one of the groups within the Lesbian Feminist Union. We offered classes and events as an alternative to traditional religion. When I left there, I took the seeds of what has become the largest goddess religion in the United States, and those seeds were planted through the Lesbian Feminist Union.

One night, we got a call at the bar saying there was a pro-choice group having a meeting at a church nearby. They were totally surrounded by Right-to-Lifers, and they didn’t know what to do. So about 40 women went over to the church and formed a circle around the women who were being heckled. That gave them enough time to pick another place to meet, at a private home. Then we formed a line that let the pro-choice women leave. Then, when we went to our cars, the protesters thought we were going to the meeting and followed us instead of them.

I also worked for the YWCA down the street, Third St., at the Creative Employment Project. We got jobs for hundreds of lesbians in nontraditional work and in the trades. Louisville had a lot of industry and factory work. I worked there from 1976 to 1982.

In 1982, I left Kentucky because my ex-husband was threatening to sue me for custody of our son. Many of my friends had already lost custody of children in the courts. The day before I was to be served papers, I took my nine-year-old son and left Kentucky. My partner, my son, and I moved to Madison, Wisconsin, because it was the only state in the country where it was legal to be gay or lesbian. Interestingly, within the next couple of years, three other women from Louisville joined us.

By moving to Wisconsin, we felt a little guilty about leaving what seemed to be the front lines of the movement because after we had been here for a while, we realized how hard we had been working in Louisville to be safe. We found that things that had been cutting-edge activism, and the organizing we had done in Louisville, were considered passé in Wisconsin. We went from the avant garde to middle of the road. Each of us, the five of us who moved to Madison (Wisconsin), continued the work we had begun in Louisville, bringing our Southern lesbian culture to Wisconsin, and moving forward from there.

Rose Norman: I’m impressed by the speed with which things happened.

Jade River: I was really moved by the level of fear and oppression in Louisville, and the amount of danger that women were in. I was determined to make a safe place for us to be. When I got fired from my job, I could work on getting the bar going within a very short period of time. The Lesbian Feminist Union was already happening. We just incorporated that into the bar, so it became like a cultural center. Setting up a bar would normally have been a lot of work. It wasn’t for us because we walked into a place that was fully set up. All we had to do was get liquor and build a stage.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University.

Do you have something you’d like to add to this tribute?

Take the leap and share the lesbian love.

Or you could write a few lines in tribute to another lesbian.

Just contact SLFA.