Mendy Knott: The Writer’s Life on the Mountain

Interview by Rose Norman, January 12, 2016

Coming Out

Rose Norman (RN): When did you come out as a lesbian, and when did you become a feminist?

Mendy Knott (MK): When I was about 19 years old, during my second year of college, I came out to my folks. They kicked me out of the house, out of the family, and out the church. My dad told me that I would never get any help from them.

I was born in Austin, Texas, into a Presbyterian minister’s family. I have a brother and two sisters. We moved about every four to six years all over the South. I’ve lived in Austin, Sugar Land, and Houston, Texas; and Minden, Louisiana.

I finished high school in Jackson, Mississippi; started college at Rhodes in Memphis, Tennessee; and went to Memphis State University [now University of Memphis]. I couldn’t sit still long enough to graduate. I became a lesbian-feminist activist and a writer.

Coming out was a huge event in my life. I loved my family. I had a strong sense of family, probably stronger than the other siblings in my family. I was on my own, sad, depressed, and freaked out.

I had a girlfriend. Then, I became an alcoholic. I drank a lot. From age 21 to 31, I drank very heavily, as if I would like to die. I didn’t think I would live past 30. But I did because I got sober.

As soon as I came out, I became a feminist, and I’ve stayed one. I marched with the early feminists trying to get the damn Equal Rights Amendment passed. Sometimes I think I’m the only one in the room. To me, equal rights for women is never going to be solved until we have them, until they’re a law. It’s just like gay marriage. How is it we got gay marriage before equal rights for women? I haven’t figured this out yet.

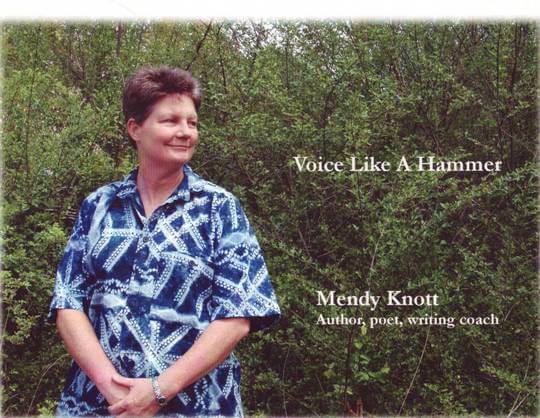

Biographical Note

Mendy Knott lives in Swannanoa, North Carolina. Her work reflects her experiences as a former police officer, military veteran, and Southern preacher’s kid.

She is an award-winning, screenplay writer and poet. Her book of poetry, A Little Lazarus, was published by Half Acre Press in 2010. She has also published a legacy cookbook of her family’s cooking, Across the ARK-LA-TEX: A Cross Family Cookbook (Limbertwig Press, 2010), and she edited Raising Voices: A Café of Our Own Anthology (Burning Bush Press, 1997).

Becoming a Writer

Once I started policing in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1985, I knew that I couldn’t drink and police, and I chose policing. I was working for DeKalb County as a police officer at Emory University in Atlanta. That was my first policing job; I had been to the Police Academy in Clayton County, Georgia. It was about that time that I started going to Womonwrites, when I began writing.

At Womonwrites, I went with the idea of leading a workshop on writing about sexuality. I was very into sexuality then. Since I had quit drinking, I was trying to replace the kick of drinking with sex. I was fairly good looking then, especially after I quit drinking. And I was in a cop uniform, which made me kind of an attractive butch lesbian. At Womonwrites, I met a woman who is a fine writer and a fine musician who was into S/M [sadism/masochism] at the time. I got quite a thrill from all that. I wrote many sexy things during that time. I wrote about her, as well as about S/M sexuality, and other kinds of sexuality.

In grade school, I knew I wanted two things.

I was going to live in these mountains one day, and I wanted to be a writer.

I think I was a writer from the time I was a kid, from the time I could pick up a pencil and read a book. From that time on, I wanted to be a writer. I remember very clearly, when I was a youngster, my dad would come over to the Presbyterian camp at Montreat, near Asheville, North Carolina, and the rest of the family would stay in the mountains nearby. In grade school, I knew I wanted two things. I was going to live in these mountains one day, and I wanted to be a writer. Yes, I got way off track along the way, but I came back to those two things. When I quit policing, I moved to Asheville, to the mountains that I love. And I began writing on a steady basis.

During my policing, I did not write on a steady basis. It was hard enough just to stay alive. When I quit Emory [University] , which was boring to me, I went to Fulton County, Georgia, working just inside and outside the city limits there, in the housing projects. That was quite a job. I did that for about four years. At the end of that, I realized I didn’t want to give my life for that. I’d rather be a writer and live in a broom closet than do any more policing and risk my life.

I just put pen to paper, and the first thing I did was to write a novel. It was a fantasy novel, post-apocalyptic, and it was all about lesbians in a big camp. I took all the people I knew, all my friends, all the lesbians from my community in Atlanta, and put them in the novel. It was actually a pretty decent book. I sent it off to several different publishers, one of them a new lesbian press. I think it was Rising Tide Press.

The publisher called me to say that they wanted the book, and they wanted a series of two more. I was elated! This was the first thing I’d written. I waited and waited for the contract. I had borrowed some money. Then, they sent the book back, saying that they had reconsidered. I was totally blown away.

I have never written a piece of fiction since. I felt really screwed over by a lesbian press. I had believed they would treat me right, but they did not. It was hard for me to figure out that, just because you’re a lesbian trying to connect with a lesbian business, you’re going to be treated right. That really opened my eyes and made me distrustful of the publishing process. Within a year, a book much like mine that I had submitted came out from the same press. It was a very strange occurrence in my life.

Writing saved my life.

I’ve written at least 500 poems, maybe 800, over the 18 years since I began writing in 1993. I want to say that poetry and writing can change your life. Poetry is a great place to start because you can do that in a day. Every day you can write a little poem. Write down the things you see, you hear, you smell. Jot things down that stand out to you.

Writing saved my life. I quit policing to write. I’m sure that saved me from death when I was policing there in Fulton County. It was just too hard then, all the crack in the projects. I can genuinely say that writing saved my life, and it can save other people’s, too. Womonwrites conferences played a tremendous role in my life. I attended the conferences for a long time. Just knowing it was there made an important difference for me.

I am the co-writer of many songs for the band formerly known as Roxie Watson, now called Just Roxie. I collaborated with Lenny Lasater who wrote the tunes while I wrote lyrics. They have long been a part of Roxie’s repertoire.

Working at Malaprop’s Bookstore

I went in to Malaprop’s Bookstore and they hired me. I didn’t even know how to run a cash register. There was also an opening for someone to run their women’s open mic, and I took it. I had written plays, poems, short stories by that time. Once I got started, I was hugely prolific. I decided to turn to poetry after that bad experience with the novel, although I did write a short story that won a prize at Malaprop’s.

As a beginning writer, especially an older writer–I was 36 or 37 by then–I’d waited all that time, and it’s like a dam bursting. You have a whole lot of energy around your work. I wrote a lot at that time. The open mic was called A Cafe of Our Own, and it went on for seven or eight years. There were 60 and 70 people coming to listen, and as many as 15 to 17 readers. It was a huge affair there at the coffee shop at Malaprop’s.

Because it was held in a bookstore, I felt strongly about not reading explicitly sexual material there. I got criticized for censoring people, but there were kids coming in there. I said, “Why don’t we have an event that’s for adult women only, where writers can read anything they want, no holds barred?” We had it in the basement of the bookstore, and called it Down and Dirty. That was a very lucrative thing for me. It’s hard to be a poet and a bookseller, and that’s pretty much how I made my living. We could sell beer and wine at Down and Dirty, and they were hugely attended. We filled the space.

Malaprop’s Is Not a Feminist Bookstore

RN: Are you saying that Malaprop’s was not a feminist bookstore?

MK: Malaprop’s would never, ever want to be listed as a feminist bookstore, even though it was mostly women and mostly lesbians running the place at one time. That’s when it was in the smaller location down the street from their current location. They are enormously popular, outgrowing that first space.

The manager, Jane Voorhees, and the founder and owner, Emoke B’Racz, were lesbians. Emoke would never want to sell 51% books by and about women; she would not cut her sales to do that. She would rather reach out to the entire community. She wouldn’t do it now, and she wouldn’t do it then. I’m sure she considers herself a strong feminist. But she’s also strong-headed.

My feeling is that poetry and writing cross all barriers and planes. We should be open to every single one of them as a valid way to express ourselves and, in particular, open to women whose greatest need is to express themselves.

We had a falling out, and I can’t even read my writing there. It’s been years since I worked there, since 2001 or 2002, and gave readings there. She [Emoke] has never forgiven me. I’m not even sure what I did. She said I’m not a team player. As a poet herself, maybe it was hard for her to watch how popular my readings were. She didn’t feel that a lot of us were real poets. There’s a huge rift between the academic poets, street poets, performance poets, and slam poets. Did you get your master’s degree? It’s really too bad. My feeling is that poetry and writing cross all barriers and planes. We should be open to every single one of them as a valid way to express ourselves, and in particular, open to women whose greatest need is to express themselves.

It is not all women who are running Malaprop’s now. The manager is a part-owner, a woman and a really nice person, not a lesbian. There are a lot of guys working there. The staff has completely changed from the staff I knew when I worked there. The owner is more focused on making money, and probably thinking of retirement now. That would be good for me. I could read at Malaprop’s again.

RN: How did Malaprop’s function like a lesbian feminist cultural center, a cultural mecca, even though it didn’t identify as a feminist bookstore?

MK: That is a good question. All the lesbians came there. At the beginning, pretty much all the staff were lesbian. We carried a really large section of lesbian and feminist books, much more than they have there now. We would order anything for anybody.

Malaprop’s was a mecca for lesbians because we had a really good bulletin board, one that took up a whole wall. People put all kinds of notices up there: apartments for rent, buildings for rent, work needed, every event going on downtown, everything going on anywhere. Everything was on that bulletin board.

People called up the bookstore asking all kinds of questions, like someone looking for someone to keep their dog while they went to Womonwrites. Sure enough, someone would answer them. This was our challenge: to answer their questions. Someone might come in the store to ask about a red book with the author’s last name maybe starting with a C. We could find that book.

Women’s voices were going to be heard there, and everybody knew that.

Almost every lesbian in town knew about the open mic, and they came to it every month. The open mic was the community meeting place then. Women’s voices were going to be heard there, and everybody knew that. No doubt about it, Malaprop’s started out and continued for maybe ten years to be the place for women to go—for lesbians, for feminists, for hippies, for anybody “alternative.” A lot of straight people in Asheville stayed away because they were scared of the people and the kinds of books that we sold. We had books on witchcraft, on everything, you name it.

When that whole censorship thing came down after the 9/11 terrorist attack, they started screwing down on libraries and bookstores. They wanted to know who got what. We fought like hell against the violation of privacy. Emoke was giving no names of our customers or what they ordered. That was fun, being on the fighting end of protecting readers’ rights.

Pete Seeger’s sister, Peggy Seeger, used to come in there. She asked for the recipe for my poppyseed cake.

I wouldn’t say we actually flirted with the lesbians who came in the store, but we were all extra friendly. We were friendly to everybody. It was a wonderful place to work, especially when Jane Voorhees was the manager. We played cool background music on the sound system. They sold delicious coffee drinks and food. I made brownies and cakes that they sold there. Pete Seeger’s sister, Peggy Seeger, used to come in there. She asked for the recipe for my poppyseed cake.

Asheville, North Carolina’s Boom as a Cultural Center

RN: How did you find Asheville, North Carolina?

MK: Asheville’s downtown is booming now, and Malaprop’s is one of the biggest and most popular bookstores in the Southeast. A group of about ten business owners worked to bring vitality back to the downtown scene, and Emoke was part of that. Artists and poets were involved, too. All of those people wanted to get their work out there, and they came downtown. Slowly but surely, more and more independent businesses opened downtown. I can’t think of a single big-box store downtown, not even a Walgreen’s. Of course, you’ll find all of that outside of the downtown area.

There’s a church downtown called Jubilee where I read quite a few times. The minister is Howard Hanger, and he includes all kind of poetry, music, and dance [in his services]. It’s incredible. I like that place, and I can read there anytime. It’s a huge audience. He has three services, and two of the services have at least 300 people attending. It’s a nice place to read, and people are really responsive to me. I’ve actually preached a sermon or two there, standing in for Howard. That was a great honor.

I swear that poetry can change a place so much. It cannot be overstated

how much poets had to do with what happened in Asheville.

Downtown Asheville is really beautiful. It’s such a great place to hang out and do stuff. I have to admit, however, that I’m more of a country person. Asheville has increased so much in popularity, and there’s so much money here now, that it’s not the same as when I first came here. There is nothing like being on the cultural edge of a town that is starting to boom, to feel it becoming a better place, and including all the arts in that. I swear that poetry can change a place so much. It cannot be overstated how much poets had to do with what happened in Asheville.

Writing

I was in Asheville at a very lucky time. I wanted to read to everybody. I was asked to perform with the women’s chorus in Asheville. They wanted to do a piece of mine. I had written one I thought would work, “In My Dreams.” It was something that I wrote for Martin Luther King Day about freedom and what that means. They put it to music. We performed it, and Diana Wortham, the director of the chorus, got a standing ovation two nights in a row when they performed that piece. Womansong Concert Program 1999

I felt so good about what I was doing with my life. I was leading writing workshops at that time, and I felt I was bringing people to the point where they could stand up and use their voices, especially women. Only women could read their work at the events at Café of Our Own. Men could come to the performances, but couldn’t read. There was a little guff around that and about the transgender issue. I kept it to women only for the readings at that open mic.

One thing that made it possible for me to live my life as a writer is that I got a settlement from the Veterans Administration from being raped in the military. They also messed up on a medical procedure that opened a can of worms; they had to settle with me on that. I believe the military owed me that. I was in the military from 1978 to 1982, and there weren’t many women in it then. Even now, it hasn’t changed. There are a lot of rapes and there is a lot of violence against women. They keep telling me it happens to men, too, but that is not my concern. My main concern is and always will be with women.

Men Only Screenplay, 2008

RN: What about your screenplay?

MK: I wrote an award-winning screenplay for an international, gay screenplay contest called One in Ten. Mine won second place. It was called Men Only. It was about a fishing contest at this big lake where the contest was for men only. The butch women in the town object to this restriction. They dress up as men to participate in the contest and they win. Then, they get exposed as women. There is a preacher who doesn’t want them in the town, where these women have lived all their lives.

The women wanted to win the contest to give the prize money to that preacher’s son, who has leukemia, and whose family has no real medical insurance. There’s romantic love in it and also an abusive father who is one of the fishermen. It shows how things come together and fall apart. It goes back into the childhood of these people and how they became who they are. It’s about their friendships with each other.

Men Only had a completely lesbian cast, and I put it on as a reading at the Goddess Festival in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It was just going to be a reading, then we decided to stage it. I had to make a lot of changes to it. I became a narrator. We had benches for boats, and they had little outfits. It was a hoot, just hilarious. Everybody loved it. I loved it, I loved seeing it come alive. We made the most money for the Goddess Festival of anything else that happened there. I also hosted a Women’s Open Mic in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It’s called HOWL and is still going on.

There are just not enough gay people, the way we know gay people, in movies and TV. While we have become part of TV shows and movies, it’s nothing like in my screenplay, which is full of happy lesbians, and butch lesbians with their friendships. I’m sure the butch lesbian part is why nobody will touch it. Even though my play won second place, it’s too good-hearted and too butch to be picked up. There’s no killing, no blood. The bad guy only gets pushed in the lake, but that’s as far as it goes.

I’m not sure how the younger generation even feel about butches. It’s a weird thing. They want to be genderless. I went to a conference for older lesbians in Richmond, Virginia, where one woman said, “Gosh, even dogs come in male and female.” There is gender. You can pretend to be genderless. Gender is loaded, but society put that burden on us.”

Arrowmont

I’m now working on a memoir. I just came back from a really great week, January 2 to 9 [2016], at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. It has always been a visual arts thing, and we were the first writers to be invited. The Pentaculum, as it’s called, is by invitation only. I was really proud to be invited.

They gave us three meals a day, a desk, a room, and all the outlets you needed to plug in. We got fed and we wrote. It was the most incredible gift that I gave myself. I did have to pay, but it was cheap for what I got out of it. I worked on my memoir, and I learned a whole lot by discussing things with the other writers. There were ten writers there.

That has put me in a new place with my writing as far as my commitment. I even got a tattoo on my arm, a hand holding a quill, with the words “Arrowmont Pentaculum.” My commitment to what I learned there and how I felt was that strong.

Marriage

I lived with Leigh Wilkerson. We got officially married in the state of North Carolina. We got a civil union in Vermont in 2000, then had a renewal of our vows after 10 years, in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Then, we got officially married in North Carolina when the state approved same-sex marriages. When the US Supreme Court decided it was OK for queers to marry, we celebrated again.

Leigh was a farmer, a beekeeper, and a very good writer. We met in the mountains where she was working on a farm producing day lilies, and working as a nurse. A couple of years after knowing each other as poets, we fell in love.

Burnsville

At that time, I was focused on my little town of Burnsville, North Carolina. It’s where I lived, where I bought my food, where I wanted to be. Burnsville was becoming a bedroom community for Asheville. They’re building a four-lane highway to there now. That might make Burnsville a more popular place.

I had a little place to give readings in Micaville, right at the end of the county road where I lived. There were two stores: an art store and a coffee shop called Maples where we had readings, called Poets Under the Maples, once a month. For the first time, I let everyone read, regardless of gender. It didn’t matter how many people showed up. We sat, we read, and we talked. It’s was a significant beginning.

I do believe that every human being should get to be how they are and who they are. Writing can heal all wounds. I believe that. It’s healed a lot of my wounds that I thought would kill me. I’ve struggled with depression, PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and a few other things. However, writing, if I am true and good about it, gets me through everything.

Sharing my writing with other writers is the second best thing you can do for myself. Finding a place to read, gather, and have a community of writers and women is hugely important. For me, it has to be mostly women. Women are the ones I trust. There are still not enough women in readings, literature, poetry, writing, acting, directors, or president. I’m tired of waiting. I did live long enough to see gay marriage, and I’m glad about that.

RN: When and how did your estrangement from your family end?

MK: I began spending time with my parents again long before I was truly reunited with them. I just kept showing up, even though for a long time I think they still believed I would not be spending eternity with them, but that I’d be in hell. This all changed when I moved to Fayetteville, Arkansas—more mountains, the Ozarks this time—so that I could be close to them where they lived, in Little Rock, Arkansas, then an easy, three-hour drive. at a time, I spent several days to a week with them, helping them in every conceivable way. All of us were growing closer than we had ever been, even more than when I was a child. That was in 2005, and that is the date I count as the time when we truly became reunited. I was 50 years old. Nobody thought I was going to hell anymore. My dad decided that gays should be part of the church. And they both voted for Obama. Only I can know how remarkable this change in them, when they were in their 80’s, truly was.

A story about this, a memoir piece entitled “Matinee,” was published in a creative nonfiction book entitled Southern Sin: True Stories of the Sultry South and Women Behaving Badly.

Looking Back

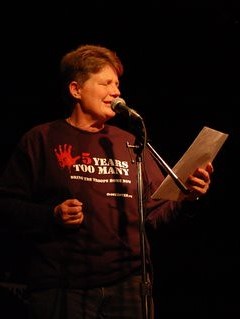

I want to thank you for including me in this project. I can’t tell you how much good it was for me to go back and look at all I’ve done with my life since coming to the mountains to be a writer. I left out so much in the interview, as I am such a creature of the present moment, keeping very little in the form of résumés. From my first poetry chapbooks, which sold out time and again, to my hundreds of performances, to plays that were produced in Atlanta by SAME, to three spoken-word CDs, to “Climbing Mt. Pisgah,” which was simply my work read aloud, to “Voice Like a Hammer: Women Respond to 9/11,” and “Peacework,” a spoken-word anthology by women on peace, I have been writing diligently, working for women, and working for the public good for a long, long time.

I don’t know how these things are so easy to forget once they have been done, at least for me. It did me a world of good to look back and to know that I have “practiced what I preach” for more years than I remember. The volume of work I’ve turned out, published, recorded, or not recorded, is truly remarkable. I had forgotten. It is good to get a reminder that, hey, you did what you said you would. You followed your dream. And it was good, as Genesis says. “It was very good.”

Mendy’s Mission Statement

I am now working on my memoir as a single woman; divorced from my partner, Leigh Wilkerson, of 25 years. I was 69 years old. I was diagnosed with breast cancer (DCIS) and underwent surgery and radiation in 2023. I bought a little house in Swannanoa, North Carolina, which is sandwiched between Black Mountain and Asheville. It was one of the hardest hit towns during the floods caused by Helene.

Always I work to build community with creativity, through writing and the arts.

I started my substack in August 2024 to have a place to practice essays for my memoir, as well as offer readings to like-minded queer folk and their allies who may feel alone as they age; as they go through major changes in their lives; and who share growing up experiences similar to mine. I always work to build community with creativity, through writing and the arts. That is my personal mission statement. Therefore, what I write will always be accessible to anyone. I invite their stories in return.

Past the bridge, you can see through the backsides of buildings swiped open by the river’s claws.

Day by day new pieces—a wall here, a slab of ceiling there—

drop from the chewed up buildings into the water below.

The quote above is an excerpt from Mendy’s Substack page titled “Landscapes: Hurricane Remains, Inside and Out.” Swannanoa, Mendy’s hometown, and surrounding areas were devastated by Hurricane Helene in September 2024.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.