Shewolf: Dedicated to Lesbian Lands

Interview by Barbara Esrig and Kate Ellison at Shewolf’s home in Melrose, Florida, February 19, 2013.

The Beginnings

I was born on Desire Street, where the street cars used to run, in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1932, which makes me 80 years old. I will be 81 in March. My father was French, and my mother was German. My mother was from New Orleans, and my father from Mississippi.

New Orleans was an easy place to live in the 1930s and ’40s, It was safe and clean. As a teenager, I used to get on the bus at my house at 8 o’clock at night to go across town to visit my friends, coming back at 10 o’clock at night, all with no fear. I wouldn’t do it now. Also, you could swim in Lake Pontchartrain then, before it was polluted.

The one thing I remember about being poor was

that to have a box of Kleenex was a big, big luxury.

I grew up in the 9th ward, which became notorious as a hard place to live. My dad was the kind of guy who went to work. He was a homemade carpenter, a homemade mechanic. He just went and got a job. I don’t remember being poor. Now, I know we were very poor. The family was run in such a way that we never bought anything that we didn’t have money for. The only thing they owed money on was the mortgage for the house. We always had food. We had clothes, but nothing fancy, nothing special. The one thing I remember about being poor was that to have a box of Kleenex was a big, big luxury. When I got my first job, the first thing I did was buy a box of Kleenex.

I remember going to school on an assistantship in Cleveland, Ohio. When I got to the Case Reserve campus and started classes, I remember being treated by Northerners as though I ate mud, and as though I were stupid. I don’t remember the dialogue, but I remember the attitude. About halfway through the first semester, when my grades were good, the attitude changed. I don’t relate my childhood with politics at all. The only thing I can remember about being a kid was that it was not kosher to associate with Black people. It was an all-white community. It was the way we lived. It wasn’t that our family had anything against Black people. We just didn’t go to school with them. They were a class of their own. There was one Black family in our neighborhood.

Biographical Note:

Jean Rose Boudreaux, aka Shewolf, was born March 19, 1932 in New Orleans, Louisiana, and she died in 2020. After graduating high school, Shewolf went to undergraduate school in Lafayette, Louisiana. She graduated in West Virginia, where she received a master’s degree in speech, psychology, and education. She received her doctorate degree in speech pathology at Case Reserve in Cleveland, Ohio.Shewolf began her career at the University of Arizona, Tucson, as a professor of speech therapy, where she earned national recognition in her field. She travelled extensively throughout the United States, compiling the “Directory of Wimmens Communities,” which was published as a guide for overnight accommodations. Shewolf touched many lives. She is held in high regard in the lesbian community.

Shewolf organized to achieve equal pay for equal work at the University of Louisiana, at the Lafayette campus in southwest Louisiana. She started holding feminist potlucks that she continued for 15 years. She wore a pantsuit to her interview for her job at the University of Louisiana, which was quite revolutionary at the time.

Read full bio.

I don’t relate my childhood with politics at all. The only thing I can remember about being a kid was that it was not kosher to associate with Black people. It was an all-white community. It was the way we lived. It wasn’t that our family had anything against Black people. We just didn’t go to school with them. They were a class of their own. There was one Black family in our neighborhood.

At one point when I was a teenager, my dad had a riding stable out on Lake Pontchartrain. He had bought this from a neighbor. On the weekend, the family would go out there. My dad hired this little Black kid. Since it was all white people out there, he stood out like a sore thumb. My dad said “Be good to him because his mother is white, and he doesn’t fit in anyplace. Nobody wants him.” That’s the only thing I remember about racial stuff at that time.

A Long Coming Out

There were no “others.” We didn’t define ourselves.I came out as a lesbian at about age eleven, and I had a girlfriend then. My mother’s best friend had a daughter, Elaine, who was about twelve years old. They used to come over to the house to stay with us, with me and my two brothers. The four of us kids would stay at the house while our parents went out for an hour or so. Elaine stayed overnight sometimes; and one time, maybe I touched her hand or something, I don’t know what I did. Anyway, the next morning she went and told her mother something. They didn’t come to visit any more.

Of course, in the 1950s and 1960s, there was no such thing as “lesbian.”

My mother never said a word. She came in and said that Elaine wouldn’t be visiting us anymore. My mother always acted as if she never knew anything was different about me. How she could not know? I only brought home girls all the time. I had only one boyfriend ever.

Of course, in the 1950s and 1960s, there was no such thing as “lesbian.” There were no “others.” We didn’t define ourselves. I was in love with a girl, and she was in love with me. We kissed; we cuddled. We read The Well of Loneliness as teenagers, I guess, maybe later. The only thing I can remember about growing up liking women was that sometime around high school, I had a boyfriend. He was a guy who wouldn’t get sexually involved because his mother wanted him to go to medical school. He was a really sweet guy, and I really cared for him.

What I remember is during that time, it was totally taboo for women or men to be together. During that first year of college, I remember that in order to get books on homosexuality at the library, you had to be a psychology major. So, I became a psychology major. The librarians had to get the key to open the cabinet to get those books out, and you had to sign as a psychology major. Otherwise, you couldn’t get the books. We thought this was perfectly normal.

I can’t remember the first time I got together with lesbians as a group. Thinking back, there was Sandy. We were together for ten years. Let’s say, in the late 1960s to late ‘70s. We had friends that we knew were lesbians. Before that, in the 1950s, it was always a single person I knew. And we always thought that we were the only ones.

Potlucks in Louisiana

In the late 1970s and early ‘80s I started a potluck group in Lafayette, Louisiana. When I went to Lafayette in 1969 or ‘70, I didn’t know anybody. I was going to the hospital to look at the program to see what kind of groups they had. I found a newcomers group. The woman leading the group was a lesbian. Of course, I didn’t know that. She asked me to stay after that first meeting, and we figured out who we were.

I asked if we had a potluck group, and she said, “No. Why not we start one?” She knew three or four women, and I knew three or four women. Between us, we got together about 15 women at her house for a potluck on a Saturday night. No rules other than meet at somebody’s house and bring some food. That went on for eight years. New women in town would come. We had about 60 women by the time one of the couples decided to have it on Sunday at 3:00 pm instead of on Saturday night. They wanted to invite some gay guys. That ruined it.

Radical Pants and Pay Equality

I’ve always considered myself a Southerner, born and raised in the South. I went to undergraduate school in Lafayette, Louisiana, and graduate school in West Virginia, when I got a master’s in education, psychology, and speech. I got my doctorate in Cleveland, Ohio. Then, I went to work at Our Lady of the Lake College in San Antonio, Texas. That was a hard job, let me tell you. Next, I went to work at the University of Arizona in Tucson, in speech and hearing. Later, I came back to Louisiana, and I went to work as a professor at what was Southwestern, now Louisiana University, in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Around 1969 to 1972, somewhere in there, I was at the University of Arizona when my old professor in Lafayette had a job opening, and he wanted me to take it. I came to campus at the University of Louisiana, and I did a workshop for them on the stage in the auditorium for all the people and students in the Speech and Hearing Department. I arrived to do my presentation in a pantsuit. This was in the late 1960s, and no woman on the campus at the time had ever dared to wear anything but a dress. I never thought much about it. It was very common for me, coming from Arizona. I had no idea what they were ogling about. That was my lesbian-feminist political experience.

After the presentation, he offered me the job. I said I’d think about it, and we negotiated back and forth. I wanted a full professorship and a certain salary. As a full professor, you got to be a member of the graduate council that ran the university. I took the job, and the first message I got from my boss, via somebody else, was “Don’t wear pantsuits on campus.” Well, I ignored that, and nobody said anything. It was still the 1970s, and I hadn’t come out yet.

I arrived to do my presentation in a pantsuit. This was in the late 1960s, and no woman

on the campus at the time had ever dared to wear anything but a dress.

The interesting thing was that as soon as I got to the campus, I somehow connected with four other women on campus who were all straight. Well, one of them was semi-straight. They were heads of departments and heads of divisions, stuff like that. My tenure was safe, and the university couldn’t throw me out. Only one of those four was tenured.

The five of us got together once a week and plotted. We didn’t know we were plotting at first. We just didn’t like the way things were on campus. Women were underpaid, and they were under-promoted. We called a meeting of all the female faculty, not more than 50 women out of maybe 200 faculty members, less than a quarter of the total faculty. We called the meeting, and nobody showed up except for us. The other women professors were too scared.

We couldn’t organize. Nobody knew anybody’s salary. We couldn’t even talk in the department about what salary we were getting. It wasn’t a written rule. It just wasn’t done. I was making well under $8,000 as a full, tenured professor, which was low in comparison to the men, who were making about 40% more although we didn’t know this as a fact. One woman in our group had a husband, and she knew what he was making. Another had a boyfriend whose salary she knew.

We think there are discrepancies in salaries and promotions,

and we’d like you to do something about it.

We went to public records to find this salary information. One of the five women ran the computers at the university, and she was the right hand to the president. Another was the head of the Business Department. Through these two women, we got records of the faculty salaries. We did comparisons, and we found out how underpaid the women were. That’s when we called the meeting, and nobody showed up. It just so happened that the president of the university was a guy I went to school with, at the same university. He was nice to me, and I was nice to him. I could go to his office to talk to him, strictly as a professional relationship. He was using me, and I was using him; and we knew it.

After “the meeting that didn’t happen,” we had some more meetings among ourselves. We went to the administration, and said, “We think there are discrepancies in salaries and promotions. We’d like you to do something about it.” They did nothing. Next, we put it all in writing, and we sent it to the EEOC [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, established in 1964] office. At first, nothing happened. One day, we got a call to come to the president’s office, and there were the EEOC. Within a year or two, the university had raised women’s salaries and changed the system of promotions.

No one ever said anything about my being a lesbian until I ran for the deanship. I was department head for seven years, and then quit. That activism [around salary and promotion] was all I did.

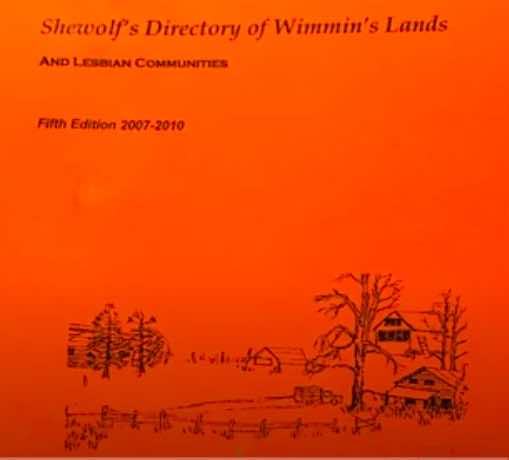

Beginning the Landyke Directory

I got involved in the landyke movement before I retired from teaching in 1985 or so. I took a trip out to California in my truck. I had one friend, Lisa, in Chico at Paradise, California. On the way out, I stopped at every women’s place I could find. I had written some letters and made some phone calls. Some major contacts were Jae [Haggard] and Lee [Lanning] at Outland, women’s land. Another contact was Sonia Johnson and Jade, also in New Mexico. I started out with a book in a specific area that had five places that were lesbian land, and only three of those five that I visited still existed.

On the way out to California, I stopped at Outland, and I was talking to Lee about all these places I had information about. She suggested sending them to her to put in Maize: A Lesbian Country Magazine, published bi-annually for many years. I was thinking of having a place of my own. Then two gals in Oregon contacted me about doing a book on lesbian lands, and I went out there to visit with them.

The more I talked with them, the more I felt as if what they wanted to do was to look at these lands and critique them. That wasn’t what I wanted to do. I wanted to do an objective, informational book. In the end, I decided to do my own book. (They never did anything with their book idea that I know of.) On the way back, I told Lee about doing my Shewolf’s Book. And that became the first edition. There were 50 places in that one, and 20 of them were in the South.

The Vision of Shewolf

Shewolf was a name that came to me in a vision quest. I was in Florida, where I had become a member of the Unitarian Universalist [UU] church, the first church membership in my life. I went with a straight friend to a weeklong UU workshop between Christmas and New Year’s. Neither of us had a girlfriend or boyfriend. We drove to Florida from Louisiana. It was the year of a freeze across the South. We got there late, the day of the Christmas dinner, about an hour before the eating was to begin. They did a big circle, and we had to choose a name to be in the circle. This was my first adventure with this kind of thing.

This must have been early 1970s. My friend said, “If you don’t think of a name, just pass.” I was sitting there ready to pass. My friend said “Sky” or something like that, and I said, “Shewolf.” Just at that minute, a white she-wolf appeared on a rock in front of me. I looked around and said, “Who said that?” That was the feeling. So that’s where the name came from. I ignored it, went back home, and was telling a friend in New Orleans about it. She came out with a big book and looked it up and said “Shewolf is the pathfinder.”

That was the year when I went out to California and began finding these paths to different places. It fit. I hadn’t retired yet, and I needed a pen name to write. Since I came to Florida, I’ve been Shewolf exclusively. These people in Florida don’t know my real name unless they had to write me a check for something.

Woman World

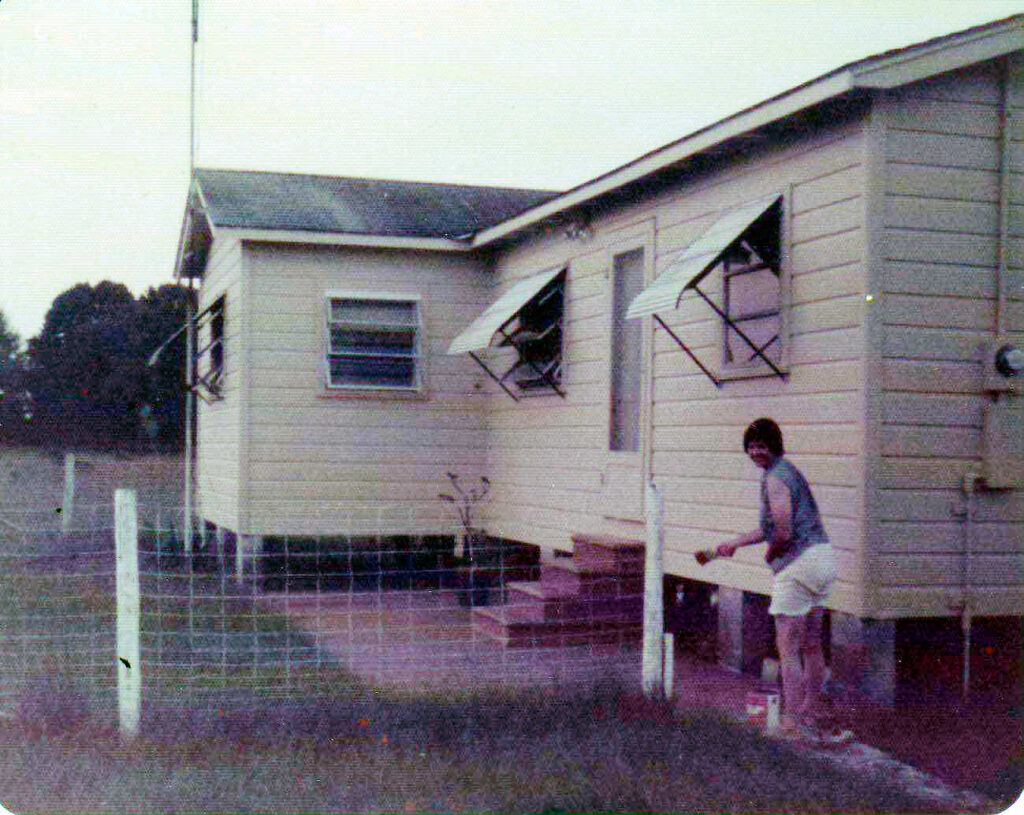

What got me interested in land communities was that my dad had bought a hundred acres in Louisiana when I was a kid, and we’d go out there. I’ve lived in cities all my life, so the land was always something wonderful. When my dad retired in the 1960s, he couldn’t really afford to retire. I bought the land from my parents. For 20 years I paid my mother and dad for the land. It was paid for when I retired.

That was Woman World, north of New Orleans, from about 1969 until 1985, roughly. The land was about 100 miles from Lafayette, where I was teaching. When I first bought it, the Interstate highway I-10 wasn’t built yet. It was about 3 hours to drive. After I-10 was built, it was only two hours. On Friday night, my girlfriend and I would go over there, bed ourselves down, get up on Saturday, work on the land, and drive back on Sunday. I raised Black Angus cows there.

There was an old, unfinished Jim Walter house that my father had built for my brother. Jim Walter is a company that franchises local crews for home building. My dad really made them build it right. When it was 70-80% finished, my brother and his wife were going to buy it. His bride-to-be decided she didn’t want to live out there in the country, and my dad took it back. I got the unfinished house, and a barn that had lost its roof in a hurricane.

I raised Black Angus cattle for about six years. They were supposed to be for meat, but I only sold some little bulls to the local agriculture agents for stud purposes. Before we had the Black Angus, I started off by buying little, 4-year old calves from a dairy. Sandy and I used to go to auctions at Target Blue Ranch. We bought these little calves, and we bottle fed them for six weeks or so. Then, they were able to eat grain. When they were big enough to slaughter, we took them to the slaughter house where they were made into meat. We got boxes of frozen steaks and such. We put them on the table, and we couldn’t eat them. We just sat there and looked at them. I don’t know what we did with them.

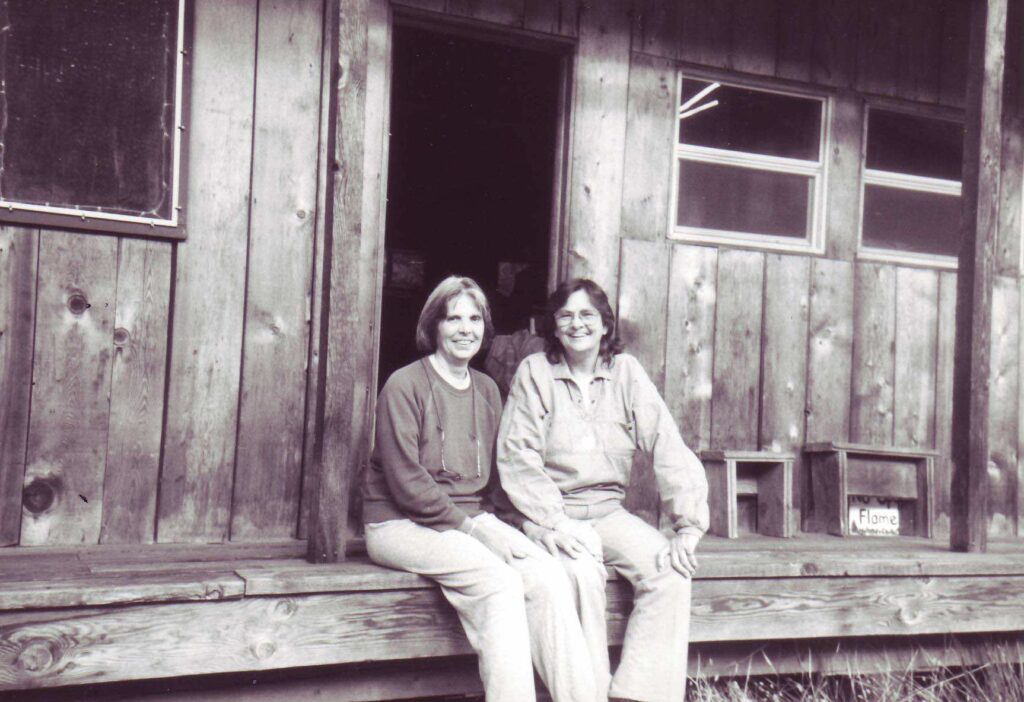

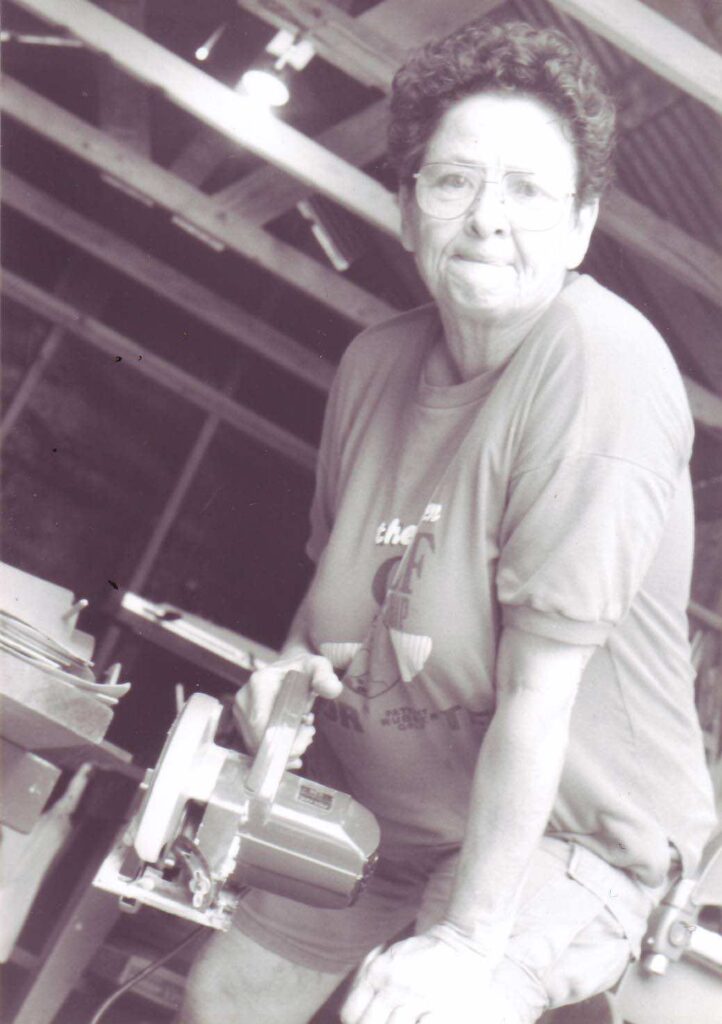

On that land, I taught women basic carpentry. Women could go back to their land and build basic cabins. I had four or five workshops a year for about twelve years. People would come to the land and live there. They’d set up a kitchen, and I would teach them. Sometimes they would just learn how to make different kinds of sawhorses. The idea was that women would come and stay there, and then they’d come back and live there. That was my big purpose in being there. They’d come, they’d eat, they’d sleep, and they’d go to the workshops. I was paying for the food most of the time. I used up about $50,000 just having workshops because people couldn’t pay to come to the workshops. They would just come.

I had several women who came and lived on the land. A couple of gals signed up for two years. I was trying to cordon off land so that women would have two or three acres of land to live on forever. That never really worked out. They all had reasons for coming and reasons for leaving. You could analyze each one. Each one was different. It was never a long-term community like SPIRAL or Sugarloaf or Pagoda, where there were continuously four, five, six women there at one time.

I think a lot of people were afraid of the South, or were afraid to come to Louisiana. They had unfounded fears. People would write asking if we had alligators. It was really unrealistic stuff. I went to lots of conventions. I went to the National Women’s Music Festival in Bloomington twice. I did workshops at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, at the Southern festivals, and at Silver Threads. When I would do workshops about women’s lands, the questions they invariably had about the South were unbelievable. Alligators.

“You are never going to find five lesbians who want

to do the same thing at the same time in the same way.”

Most of the women that came to Woman World were pretty nice gals, and they did a nice job. But they all had issues. Woman World started out being a landyke place where women could come to live, and it turned into a workshop place where women came to learn stuff and to leave. After a while, I gave up trying to make it into one. But we had some great times. I had seventeen years there.

When I first started out looking at lands and trying to make a community at Woman World, my little wise friend in California, who was about ten or fifteen years younger than I was, looked me in the eye. She said, “You are never going to find five lesbians who want to do the same thing at the same time in the same way.” She was right. Everybody has the feeling that “if you build it, they will come.” T’ain’t true.

A note from the interviewer:

We asked Shewolf what makes lesbian intentional community so difficult to create and to succeed. She said that each one of us has a vision of the community we want to create to which we are completely dedicated. Often, the ones with the biggest dreams and visions have no money for bringing it into being. The ones with money go ahead and build a place. The old saying, “build it and they will come,” doesn’t always happen because we each believe so strongly in our own goals that we cannot show up for someone else’s view of community.

These places were formed for protection to keep other people from beating them up,

or whatever prejudice they were experiencing.

Everybody has the feeling that they know how they want it—they want to eat vegetarian, they want to grow their own food, get off the grid, cut themselves off from the mainstream. And they want to do all of this without any money. The women who were the most dedicated to doing this never had any money. The few that had money went out and bought their own place, or set up their own place, saying, “ya’ll come.” And nobody came. And it’s the same all over.

One of the reasons Oregon was so successful in having so many women’s land communities is that at the time it was a real thing to need protection. They were afraid. These places were formed for protection, to keep other people from beating them up, or whatever prejudice they were experiencing. The things that happened to the Hensons in Mississippi were happening to other women, but nobody knew about it. The story of Sister Spirit is the story of a lot of places that weren’t on Oprah.

There’s not a lot more women’s land now than before. In every edition of the landyke directory, they added some, but they lost several. The Pagoda, Womanshare in Oregon, Sugarloaf, and LongLeaf are old enough that they’ve been in every edition.

RVing Women and Resort Communities

RVing Women, that is, women who live in and travel around in recreational vehicles, is an organization that Zoe [Swanagon] and Lovern [King] started, back in the 1960s, I guess. The stories are connected to Carefree, a lesbian community in Florida. They went under the guise of RVing Women for many years. Then, in Tallahassee, at the national convention of RVing Women, the issue came up. Just as it did in NOW [National Organization of Women].

I was the master of ceremonies at the convention that year. Something was said on the stage about lesbians. Four straight women sitting in the back got up and left indignantly. The issue was brought up, and we said, “Well, 75% of this organization is lesbian, so give it up.” Then Zoe and Lovern invited people on the RV email list to come to Pueblo, Arizona, an RV park that they were gradually buying up to sell to lesbians. They also bought the park across the street, Superstition Mountain Resort. Now there are at least 500 lesbians there. They came from all over. There’s no way to know how many were Southern.

Gina [Razete] and Cathy [Groene] went there, and they decided they could do the same thing back home in Florida, near Fort Myers. That became Carefree Resort. It’s 25 acres. They made a beautiful RV park. The connection is that RVing Women led to those two lesbian RV parks in Arizona, and that led to Carefree, the first resort community built exclusively for women. Rainbow Village in New Mexico was likewise built for us women, and was very expensive.

RV communities and lesbian lands are totally different things. There’s no resemblance whatsoever. RV communities are people who live in RVs. On lesbians lands, they could live in anything from shacks to RVs to mansions. There’s no relationship to one another. Carefree just happens to be both. Gina and Cathy have built another community in Boone, North Carolina, an offshoot from Carefree. It has chalets. They made it gay and lesbian, letting men live there.

See also:

Interview in 2003 by Arden Eversmeyer for the Old Lesbians Oral Herstory Project, archived at Smith College. Transcript available on request.

Shewolf Remembrance Gathering (May 2020), sponsored by Sinister Wisdom.

Do you have something you’d like to add to this tribute?

Take the leap and share the lesbian love.

Or you could write a few lines in tribute to another lesbian.

Just contact SLFA.