My Mother Was Many Things

This story was inspired by Jaime Harker’s book, The Lesbian South, in which she wrote about June Arnold. The story, in a different, original format, was read at a talk given at the University of Mississippi for the Southeastern Women’s Studies Association (SEWSA).

My mother, June, was many things: novelist, publisher, lover, carpenter, lesbian feminist activist, Southern rebel, and my mother. Growing up in Memphis during the depression, June and Fanny, two conflicting siblings, spent their free time in childhood roaming the landscape on their own. They had moved to Houston when their father died so that the family could be helped out financially by their mother’s wealthy brother. June was 12 years old when she rode on the train with her father’s body in a pine box. Later, she recounted that she would go outside each night to wish upon a star for her father to get well.

In Houston, June and Fanny grew up in a world of privilege, one that came with all the trappings of entitlement. Despite this, June saw herself as an outsider. My younger sister said that the message our mother, June, gave her was: How would you feel if that happened to you?

Later, June said that status and hierarchy were divisive, and that she wanted no part of it. “Such status would divide me from my sisters, and perpetuate the same hierarchies where one person is good/talented/beautiful, and where others are not. It would bring us no closer to a world where women’s art is a total, complex expression of our voices.” [From “Feminist Presses & Feminist Politics,” Quest: A Feminist Quarterly III, no. 1. (Summer, 1976).]

The Move to New York City and the First Published Novel

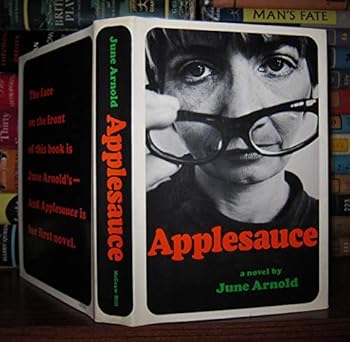

In 1958, at the age of 27 and with three daughters, June returned to get a master’s degree in literature at Rice University in Houston, Texas. By 1959, she had five children when her fourth child drowned in a swimming pool accident. Mentally shattered, June moved herself and her children away from an abusive ex-husband in Texas to New York City. She had begun her first published novel in Texas, and she finished it in New York. Her novel was about how social roles and societal expectations can peel, core, and squash you. This novel was called Applesauce.

In New York City, June enrolled her four children in a school founded and run by lesbians. After renting and moving often, June decided to buy a warehouse for $60,000, which was a good price, even then, for a West Village loft building. We fixed it up together, scouring the brick, painting radiators, waiting weeks while polyurethane was applied to the floors. I watched her rewire a lamp, make a perfect angle with and without a miter saw, and fix what needed to be fixed.

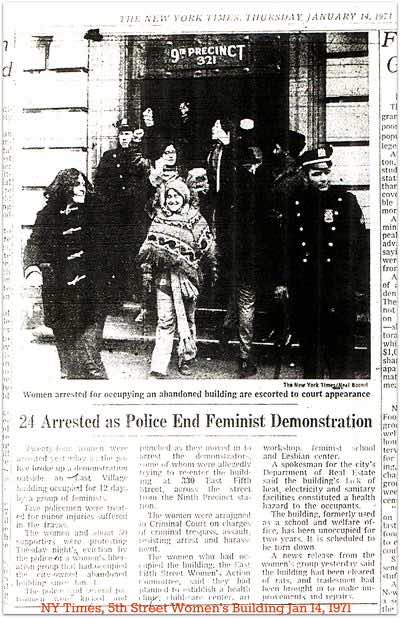

In the late 1960s, June got involved in housing rights. My younger sister and I joined her at one of the squattings [illegal occupations]. We got arrested together, and we sang folk songs through the steel bars of our cell.

The Cook and the Carpenter

June’s second novel, The Cook and the Carpenter, used a Swahili word for male and female pronouns. She says in the unpaginated front: “Since the differences between men and women are so obvious to all, so impossible to confuse, whether we are speaking of learned behavior or inherent characteristics; ordinary conversation or furious passion; work or intimate relationships, the author understands that it is no longer necessary to distinguish between men and women in this novel. I’ve therefore used one pronoun for both, trusting the reader to know which is which.” The Cook and the Carpenter was imagined from a feminist action takeover of an abandoned building on the Lower East Side.

The 5th Street Takeover

Reeni Goldin was at the file cabinet in the Women’s Center on 22nd Street when this stranger, my mother, peered over her shoulder, asking: “Are you looking up housing, too?” The takeover planning began around my mother’s dining room table, a Southern fixture. Reeni and my mother rode the streets on bicycles, looking at the abandoned, city-owned buildings they had staked out together.

That winter women came out like daffodils bursting from snow. Women reconnoitered, went out on reconnaissance missions, and expanded forces, growing into an action that would establish a community building with nine centers to benefit women.

The 5th Street building was seized by women on Jan 1, 1971. We climbed up the crusty fire escape, edged through a window that had sneakily been broken by the reconnaissance team, crawled onto tenuous floorboards covered in grime and dust, and set up our female troops with only one male, my eleven-year-old brother, Gus. He sported a red hat in the Australian bush fashion, tacked up on one side.

Here is 5th St. from the vantage point of Gus. “I remember going in that first night, and how dangerously dark it was. There was lots of broken glass, loose wires, and debris. Strategic plans were in place with various people to deal with building issues, and to get the power on. The jet engine heater, loud and smelly, had a sign on it that actually said ‘Mr. Heater,’ which someone immediately crossed out to read ‘Sister Heater.’” [Quotation provided by June’s son Gus Arnold.]

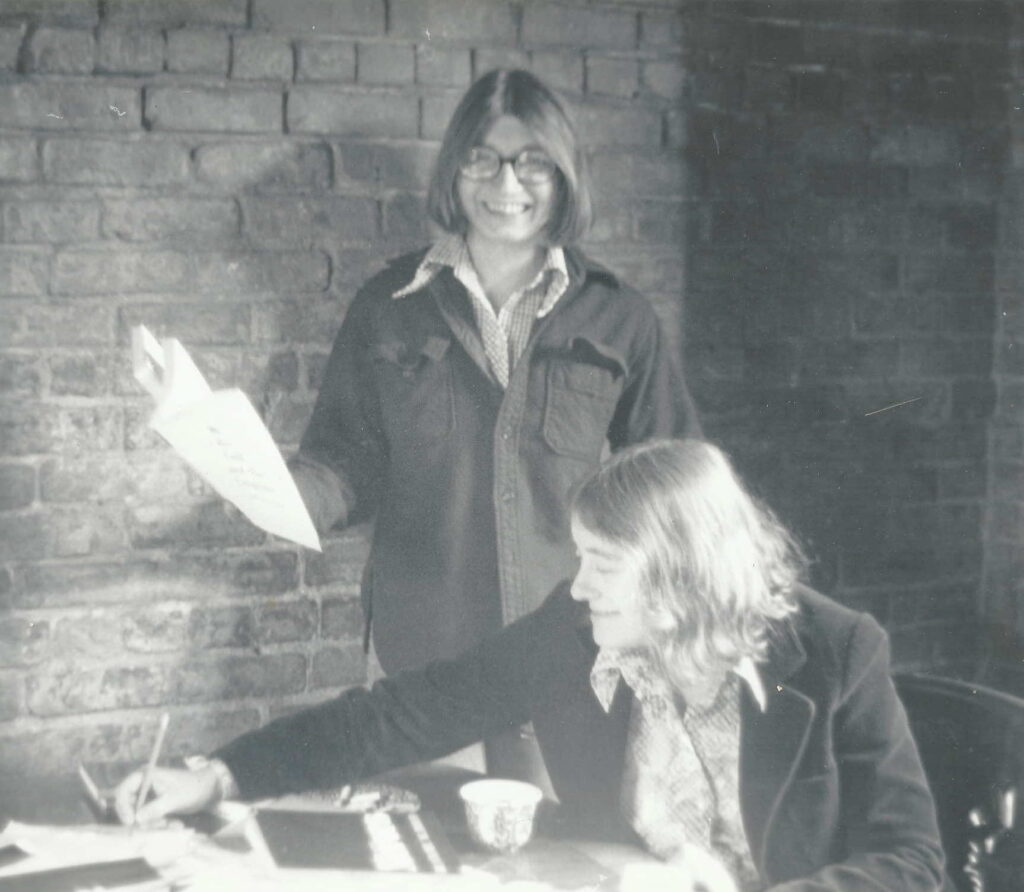

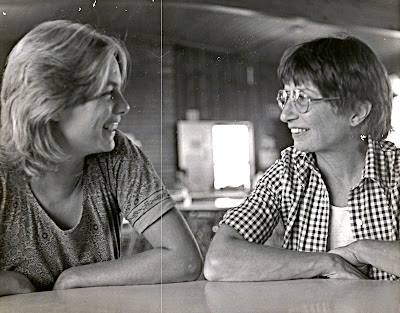

At forty, my mother met the love of her life, Parke Bowman, also known as Patty, a lawyer. In 1972, with $15,000, they began the publishing company, Daughters, Inc., in a Vermont farmhouse that my mother re-plumbed and re-wired herself. Daughters published 23 titles by lesbians and women, beginning with The Cook and the Carpenter by June Arnold and Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown. Later, they published Lover by Bertha Harris, and Monique Wittig’s, The Opoponax. Bertha Harris and Charlotte Bunch joined as editors of the company. June later gifted the company in its entirety to Patty Bowman. After a few years of split-politics and relationship struggles, and with plenty of alcohol in the mix, June’s gift to Patty was an act of love.

Daughters and Code Names

Visiting home from college one evening, I pulled open the heavy, steel front door to the loft, and I saw that someone had spray-painted the side of the building in bright, yellow graffiti: “This building belongs to rich pretty lesbians who can afford to say no.” The tag was in reference to an article about Daughters, Inc. in the New York Times magazine section in which my mother had said: “Women can afford to say no [to Madison Avenue].”

My mother was not alone in believing that women needed to have full control over their writing, their presses, their distribution. She believed that art is politics, saying, “It is vital that we maintain control over our future, that we spend the energy of our imaginations and criticisms building feminist institutions that will benefit women, both in money and skills.” [“Feminist Presses & Feminist Politics,” Quest: A Feminist Quarterly 3.1 (Summer 1976) ]

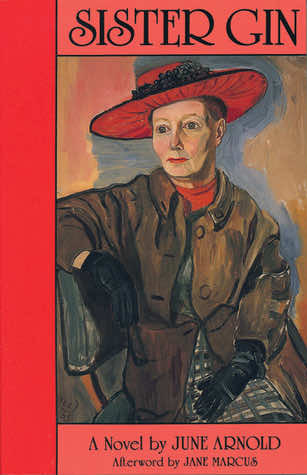

Bertha Harris and Patty Bowman were sitting with my mother in the living room when I came in on a discussion about the future of Daughters in relationship to the graffiti. “If the publishing company tanks, we can always start a lesbian brothel. Each book title would be our code name. I’d be Sister Gin,” my mother said.

“I’d be Lover,” Bertha chimed in.

“And I’ll be the lawyer who bails you all out of jail!” Patty said, in her usual frenetic style of chain-smoking and pacing.

I said: “I’ll be the Cook. But I’m afraid all our customers will be going to Rubyfruit Jungle.”

Sister Gin, June’s third book, was about older lesbians aging, accepting being fat, and going through menopause, and about a group of older women finding and outing the town rapist by marking his forehead with the letter R. As June said in her book, “The truly free is she who can be old at any age. She will be old again as soon as her body stops being under the Moon’s dominion. The child and the old don’t go by clocks and don’t go by fear. Time took away the child and only time can bring her back.”

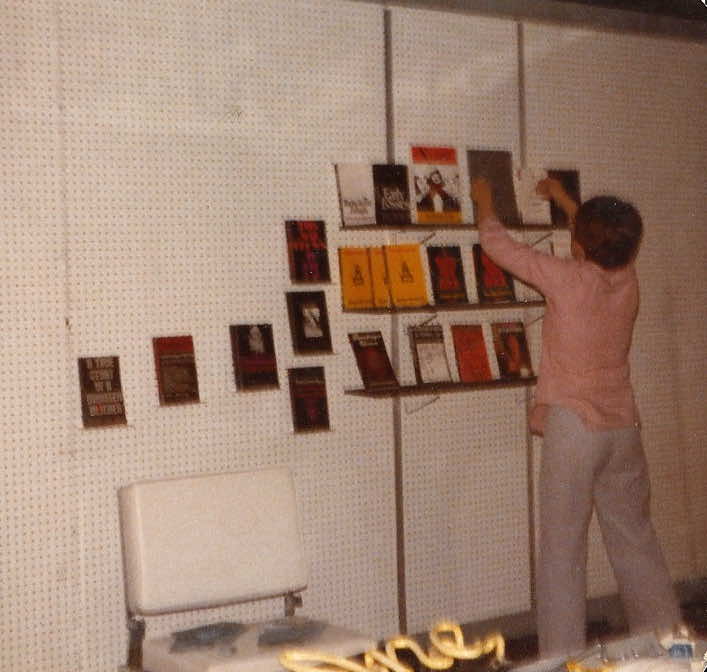

The First Women in Print Conference

The first Women in Print conference, held at a girls’ camp in Omaha, Nebraska, was another event where June was a driving force. “She wanted to see what would happen,” Judy Grahn recollected. “She took the idea out of her head and put it into action, and with some help from some other women, she invited the entire women in print movement to come. It was just amazing.” [Feminist Bookstore News (Summer Supplement, August): 1990)]

June sent invitations to all the women’s presses, feminist bookstores, and distributors that she kept on index cards. In a letter to Nancy Stockwell of Plexus, June said, “I’m looking forward to our conference like a kid to the circus.” [From the Nancy Stockwell Archives.]

The first Women in Print Conference was a wonderful success. Big Mama Rag, Lesbian Connection, Quest, Diana Press, Sinister Wisdom, Black Maria, Iowa City Women’s Press Collective, Off Our Backs, and Naiad Press were just a handful on the schedule to give talks or workshops that summer.

Kate, my older sister, attended. She was a co-owner of a woman’s gallery and feminist bookstore in New Mexico. She recalled that our mother had asked her to “organize a chili dinner” for the huge crowd on the first night. She continued, “I remember being uncertain if it would work out. But she just encouraged me to make it as normal, and with 10 times the ingredients. It was the first and last time I have ever cooked in such a huge pot! The synergy of all the women and everyone’s excitement at meeting people whose newspaper they sold, or whose bookstore they had visited or heard about, was beyond palpable. People were high on the energy. I think everyone went home fully charged to do even more.”

[From an Albuquerque newspaper at the time: “Four women, Kate Arnold, Connie Samaras, Alice Echols, and Deborah Ritchey, are acutely attuned to what they assert is a widespread pattern of discrimination against women in the art world, and their “doing something about it” involves setting up their own counter-culture center.”]

Tributes

My younger sister sums up in her own words the spirit of my mother, June, during that time period. “One trait stands out for me: sitting around the table, ideas lofting high with imagination, and everyone chipping in as the idea rolled and grew to possibility. Swimming pool in the New York City basement? Of course! Take over New York City building? Of course! Start a publishing company? Of course! What else? Anything was possible. I took that to live by.”

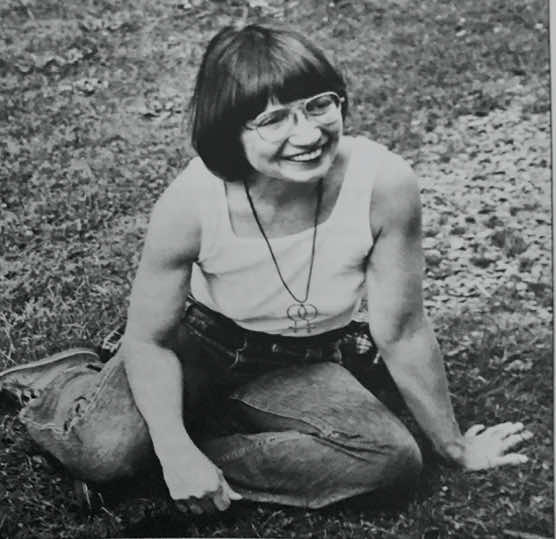

The photo of June that brings her to mind best for me was taken by Barbara Adams [see feature photo at the top of this post]. She was sitting on the grass at a feminist gathering, hair in a Dutch-boy bowl-cut, with a hammered-metal, double women’s symbol on a leather string around her neck. Her legs were at angles, one half-tucked beneath her, the other bent at the knee, thrust back. Wearing worn jeans, sneakers, and a sleeveless, white t-shirt, the expression behind her aviator glasses was thoughtfully welcoming. One wiry, muscled arm was outstretched, palm flat on the earth, the other rested on her leg, fist in a gentle clench.

Some Last Words

When she was fifty-four my mother felt her arm go numb while hammering on a bookcase in a condo that she had just purchased in Houston, Texas, for her and Patty. It was 1979. A little over a year later, she died from brain cancer. June honored the women she loved in the Women’s Movement on scraps of writing paper we found by her bed during that last year. One piece began, “We stood at the bow, which was lifted and perfectly balanced thirty-five degrees off the horizontal as if by a university of whales. We three—Audrey, Glenda, and Jane—at the bow, where all adventures begin.”

See also:

Cowan, Liza. “Side Trip: The Fifth Street Women’s Building Takeover: a Feminist Urban Action, January 1971.” Dyke: A Quarterly, July 26, 2012.