Mandy Carter at the Center of a Lesbian-Feminist Activist Hotbed

Interviews by Rose Norman by phone on March 26, 2013, through November 7, 2015 (four interviews)

Social Justice Summer Camp

Rose Norman: Tell us how you got into social justice activism, and what brought you to the South.

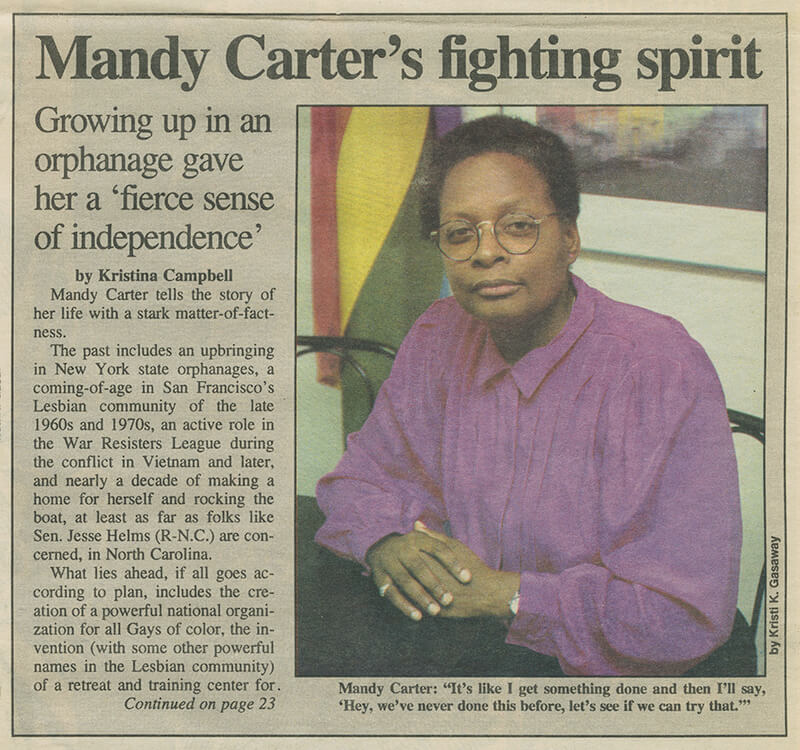

Mandy Carter: I was born in Albany, New York. The most important thing to know about my upbringing is that I was a ward of the state of New York for the first eighteen years of my life. Shortly after I was born, our mother left and never came back. My brother, Ron, my sister, Delores, and I were in an orphanage in Albany. We got split up when we were all living in a foster home. We still can’t find our older sister Delores. We don’t know if she’s dead or alive or has changed her name. I was in raised in two orphanages and one foster home: Albany Children’s Home, Schenectady Children’s Home, and, in between, a foster home in Chatham Center, New York, for four years.

Something that happened in high school is pivotal in knowing how I got involved with what I’m doing now. The Schenectady Children’s Home mainstreamed us into the school system. I went to Mount Pleasant High School in Schenectady, graduating in 1966. In the year before I graduated, a history teacher of ours brought in someone from the American Friends Service Committee or the AFSC. That one, forty-minute class changed my life.

I had never heard of Quakers [the Friends] or the AFSC, and the speaker was just a young staffer from the local AFSC office. He talked about the Quakers, and how they were down South as white allies working in the civil rights movement. He said that one of the tenets of Quakerism is the concept of the power of one: every single person has the capacity to make an impact.

Mandy Carter, born in 1948, speaks from her fifty-five years of activism as a Southern, African American, lesbian activist, organizing for social and racial justice. Carter highlights the importance of allies, and she spreads a message of hope that is deeply important in our lives today.

She attributes the influences of the Quaker-based American Friends Service Committee, the former Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, and the pacifist-based, War Resisters League for her sustained multiracial and multi-issue, intersectional organizing.

He also talked about how if your fundamental philosophy is equality and justice for all, that means that at any particular time, whatever your particular issue, it keeps your work current and relevant. I didn’t quite get that at the time, but it really stuck with me.

Going to that American Friends Service Committee summer camp for a week took me

from hearing great ideas to doing something about it.

We had just had the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, and we had duck-and-cover air raid drills in school. Then, there was the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963. All this is rolling around in my mind when he came in talking about the power of one, and about equality and justice for all. At the end of his presentation, he told us about their American Friends Service Committee High School Work Camp in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. I raised my hand and said that I’d like to go. And the rest is history.

Going to that American Friends Service Committee summer camp for a week took me from hearing great ideas to doing something about it. That experience is the key reason that I do what I do now. We read about Gandhi and nonviolence. There was a young, white, folk-singing couple, Guy and Candie Carawan, from the Highlander Center. I’d never heard of them or the Highlander Center, and I was just fixated on what they were doing in the South. They were singing and recording songs of the civil rights movement. That was just something in the news, now made real for me by them. And they told us about the Institute for the Study of Non-Violence, run by Joan Baez and Ira Sandperl, which I ended up attending. Later, after attending it, I got arrested for protesting the Vietnam War. I went to jail in 1967, and then, I got my first job, which was at the War Resister’s League in San Francisco in 1969.

RN: Civil rights activism and antiwar activism were connected for you by the Quakers. How did feminism fit in with that?

MC: In San Francisco, the antiwar movement was very male-dominated. We had the military draft at that time, and meeting after meeting, they were all run by men. We had a meeting down in Palo Alto, and they were passing around a sign-up sheet. A woman friend of mine looked at it and said, “There’s nothing but penises on this list!” For me, that made the point crystal clear.

Do you remember that speech Dr. Martin Luther King gave? Not the 1963 speech at the March on Washington, but the one on April 4, 1967, at the Riverside Church in New York. He talked about how we have to challenge what we’re doing in Vietnam. He said how can you ask Black men to go thousands of miles to another country of color, Vietnam, and kill or be killed in the name of democracy when they didn’t have democracy when they left this country, and they didn’t have democracy when they got back.

Those of us who were just a little too young for the civil rights movement, and who were very involved in the anti-Vietnam war movement, heard that and made the connection. I think that was a transformative moment for the country. Here’s a Black man who was leading the civil rights movement down South, saying now, we have to talk about the war in Vietnam against a backdrop of Black men. And he was also talking about economic justice issues. He was saying, “If we fight for the right to sit at a lunch counter, do we have any money in our pocket to buy something once we’re there?” That led to my participation in the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968.

The War Resisters League [WRL] was started in 1923 by three women:

Jessie Wallace Hughan, Tracy Mygatt, and Frances Witherspoon.

A lot of women active in the anti-Vietnam war movement were asking what they could do. There was a great group out of Boston called RESIST. They wanted to figure out how to complement the draft resistance movement, which was all men, with people who couldn’t be drafted, like women, and like men who were too old. That became a point where we felt we could have a voice and visibility. Author and pacifist, Barbara Deming, made a good point about the antiwar movement. She said that it was not only the soldiers, but the Vietnamese women and children who were harmed by that war, by all the things that happen in war, the rapes, and so on.

Note that the War Resisters League [WRL] was started in 1923 by three women: Jessie Wallace Hughan, Tracy Mygatt, and Frances Witherspoon. Thus, for me, early feminism was swirling around in the WRL. We had some very strong, powerful women in the War Resisters League. Never a meeting would happen without equal voices in the room.

Moving to the South for the War Resisters League

RN: How did you get from upstate New York to San Francisco, and then, from San Francisco to Durham, where you have lived since 1982?

MC: After I graduated high school in New York, the Schenectady Children’s Home said that they would pay for my entire college education. This was extraordinary because you “age out” of the welfare system when you turn eighteen. They were willing to put me through college if I got admitted, and if I stayed in college. I tried to do that. By then, I had heard about the Quakers, also called the Friends, and the antiwar movement. I had attended that American Friends Service Committee summer camp. I did get admitted to Hudson Valley Community College, which is part of the State University of New York system. It just wasn’t what I wanted to be doing then. I was living at the YWCA in Troy, New York. To me, it was just one more institution where I was living. I felt that I really needed to get away from institutions, including college, and possibly pursue getting involved in social justice activism.

I dropped out of junior college, and I took a bus to New York City, hoping to get a job. That was the summer of 1967. I had $80 in my pocket, which soon ran out. I was walking in the West Village one day, and I saw a sign in a window that said “Free Lunch.” It turned out to be a place run by Timothy Leary, the well-known LSD advocate. I got a job there for the summer in exchange for a place to live and answering the phone between the hours of 8:00 at night and 8:00 in the morning to tell people when they called about having bad LSD trips how to come down from them. It was an eye-opening and great summer for me.

At the end of that summer, three of us decided to hitchhike to San Francisco, California because that’s where it was happening. At that time, when you went to San Francisco like that, you went directly to the Haight Ashbury switchboard for a place to stay. The three of us went down to the Haight Ashbury switchboard, and we got a phone number of a guy named Vincent O’Connor.

I got the opportunity to go down to the Institute for the Study of Non-Violence with Ira Sandperl and Joan Baez. That took me to a “sit-in action,” from which I landed in jail with 100 other people.

Of all the people we could have met, Vincent O’Connor turned out to be a draft resister, working with the Catholic Peace Fellowship. He let me stay on because I was interested in nonviolence and what was going on, and I volunteered at the Catholic Peace Fellowship. Then, I got the opportunity to go down to the Institute for the Study of Non-Violence with Ira Sandperl and Joan Baez. That took me to a “sit-in action” at the Oakland Induction Center, from which I landed in jail with 100 other people in December 1967.

Jane Shulman came over to me and asked if I’d ever heard of the War Resisters League [WRL]. I said no. She invited me to a potluck they were having. I went, and that led to stuffing envelopes, and to a couple of trips to hear more about WRL. I went to jail again. Then, the WRL had an opening for a paid position, and I got it. That was my first “movement” job. San Francisco was right across the bridge from the Oakland Induction Center, where every single man going to Vietnam had to go first to be processed.

That’s how I got to Durham, too. When I decided to leave San Francisco, I wanted to move back east of the Mississippi because I missed having the four seasons. I asked the War Resisters League where they had an office. The one that had an opening was in Durham, North Carolina. It was the War Resisters League’s Southeast office. I interviewed and got the job.

I think of myself as a Southern, Black lesbian, and a social justice activist.

Feminism is certainly part of it.

RN: When in your life did you realize that you wanted to work on sexual orientation along with the race and class issues? Were there specific life experiences or events that led to it?

MC: When I was in San Francisco working for the War Resisters League, I knew gay men who saw themselves as people who believed in pacifism who were gay. In the beginning, I was too young to go to the lesbian bars, where you had to be 21. That was how to meet other lesbians, and the bars were also the breeding ground for queer liberation. I was doing both kinds of activism.

I’m a lesbian, but my world is defined by more than being a lesbian. I care about domestic violence. I care about fighting the Klan. I don’t mind being called a “lesbian-feminist activist.” I think of myself as a Southern, Black lesbian, and a social justice activist. Feminism is certainly part of it. I just wouldn’t necessarily tag it that way.

Cofounding SONG from the Creating Change Conference

RN: Tell us your story about how SONG started, and why you think it has lasted so long.

MC: SONG [Southerners on New Ground] came out of the Creating Change Conference in 1993. Creating Change is an annual conference for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF). That year, Ivy Young, a Black lesbian working for the NGLTF, called me to say that they had just lost the site for that year’s conference. She asked me if they could they bring it to Durham. This would be the first time they had the conference in the South, and I enthusiastically agreed, knowing what a good base of gay and lesbian activists we had in our area.

Then, we started getting phone calls from people coming to the conference asking things like, “Is there an airport down there?” and “Why are we holding it in North Carolina? Isn’t that where Jesse Helms is from?” [Jesse Helms, notorious for his devastating and extremist misogynist, white nationalist policies, was a Republican U.S. Senator from North Carolina for thirty years, 1973-2003.]

I told them “We’re holding it in North Carolina precisely because that’s where Jesse Helms is from!”

The anti-Southern bias was enormous. A few of us who knew each other decided that we would offer a workshop on what it means to be living in and organizing in the South as gay people and as lesbians. The phone calls that we got expressing bias against the South really underlined the need for that workshop. Suzanne Pharr, Mab Segrest, Pat Hussain, Joan Garner, and I organized that workshop. That one workshop, coupled with Mab’s amazing plenary speech for the conference on why we as LGBT people have to care about NAFTA and other “non-gay” issues, led to SONG. [Mab Segrest’s speech, “A Bridge, Not a Wedge,” was published in her Memoir of a Race Traitor, pp 229-246, 1994, and is accessible online through Google books.]

That was the kernel of the dream of what is still going on with SONG from a workshop that happened because of backlash against being in the South. Later we brought in Pam McMichael, who was organizing around labor issues in Kentucky, as the sixth of the SONG cofounders.

Our original statement of purpose that came out of that workshop was “building transformative models of organizing in the South” that would connect race, class, culture, gender, sexual orientation.” I think that we added the phrase “gender identity,” as well. The operative words are “transformative models of organizing.” It wasn’t just about being Southern, or gay, or lesbian. If you took all that and looked at what you were organizing around, you could see the connections.

What was important for the six of us was how to take what we were working on to show that it wasn’t just about us. It wasn’t just about being a lesbian, or a Southerner. What would be the thing we could take anywhere in the South that would let us sit at a number of different tables, tables that were not gay. One of the first things we did was to pick a non-gay issue around economic justice. The Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride around farm labor was one of the intentional things we did. We hooked up the African American history of freedom riders in the South with the farm labor organizing that was Latino/Latina. Another was the Mount Olive brand pickle boycott. SONG was at that table, too.

Organizing around broader groups than sexual orientation lets us

bring all of who we are to what we do. That has been a touchstone for SONG.

We had to go intentionally to somewhere else that wasn’t just about being gay to let people understand that being gay isn’t just about being gay. It could be around broader issues than sexual orientation. Also, for a lot of groups like the farm labor groups, there are a lot of gay and lesbian members. This approach lets them bring all of who they are to what they do. That has been a touchstone for SONG.

Right now, we are still in coalition with immigrant organizing in Georgia and Alabama. People see we show up, we’re there, we’re serious, and we mean it. They see that we’re there because of their issue, and that we all understand the justice issue across all those different levels. SONG will be a constant partner in this effort. We don’t want them to join us, them to be us. We want to see how we can move all of us forward.

There were two critical points in our growth. First, we realized it’s not just Black and white any more, and it’s not just women. The second was always to have codirectors, not just one director. The first two were Pat Hussain, a Black woman in Atlanta, and Pam McMichael, a white lesbian living in Kentucky. We decided to hire a Black gay man, Craig Washington, who took over for Pat. And we also started looking for non-Black, non-white people. The current codirectors are Paulina Helm-Hernandez, who came from the Highlander Center, and Caitlin Breedlove. [In 2025, codirectors were Jade Brooks and Carlin Rushing.]

The key word for the War Resisters League was intentional. If I’ve learned nothing else over the years, that is what I brought to SONG. It was intentional that we started with three Black and three white women. It was intentional that we looked for intersections of “–isms.” Where we are now, and all we’ve done, intentional is the word to me that is the essence of what is and what needs to be right now. That’s one reason SONG has carried on for twenty years now. Another reason is that we have so many people we partner with in the South. I think the South is much more conducive to cooperating without competing.

Pre-conference for Creating Change in 1993 and Rhythm Fest

RN: How did you all meet?

MC: Our relationship was formed because of Rhythm Fest. That’s how we knew each other. We were already going to do a workshop at the preconference about gays organizing in the South, for Creating Change in 1993. It was Mab’s speech that I referenced above. Also, it was what Pam said about the preconference when we proactively did a conversation about the intersections. SONG started doing those preconference social justice workshops at Creating Change conferences. We did them for several years.

RN: Before the conference Creating Change 1993, you had been doing preconference work on intersectionality.

MC: We did one about the film, Gay Rights, Special Rights. Mab Segrest gave a plenary speech, “A Bridge, not a Wedge,” at the Creating Change preconference. SONG came together during the meetings that we had afterward.

It was a confluence of things. The fact that Creating Change was in Durham, North Carolina, the first time it was held in the South, was what led to many other things. It’s the framing. I don’t want that to get lost.

You know, I could swear it was Suzanne Pharr who came up with the name “Southerners on New Ground.” You said in an email to me that Mab did it. My memory on that point isn’t firm. I think the main thing is that the workshop didn’t come out of the calls. It was just reinforcement about why the workshop was important to do because of those calls.

The birth of Rhythm Fest came out of all the other festivals we’d been attending.

We wanted to start a new model in the South: music, comedy, and politics.

RN: You and others started Rhythm Fest in 1990.

MC: Yes, it was. And it was because of Michelle Crone’s work with other national women’s festivals, mainly the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival and Robin Tyler’s West Coast Women’s Music and Comedy Festival. Rhythm Fest was started in the South by women who had worked at other festivals, and they thought maybe they could start their own festival to create some new culture. Barbara Savage, Michelle Crone, and Kathleen Mahoney had all worked other festivals.

The whole point of Rhythm Fest was to create a different culture. No more wrist bands, nobody treated special. [Festivals like MichFest and West Coast issued different colored wrist bands designating levels of access to different areas of the festival, such as back stage. This formed a kind of social hierarchy that Rhythm Fest resisted.]

It became a festival of people who were not wanted, or not accepted, or just changed the culture of how you would normally do a women’s festival. The only reason I joined was because Michelle Crone called and asked me. I said, “I don’t know, maybe.” The next thing I knew, I was one of the coproducers! It was a mix of the cultural and the political. I had known Michelle Crone from the peace walk that was from Durham to Seneca—from North Carolina to New York—in 1983.

[Mandy Carter organized the peace walk from Durham to Seneca County, New York. Michelle Crone was one of the organizers of the peace encampment in Seneca County that was held from July 4 to Labor Day weekend, 1983. The protesters were camped near the Seneca Army Depot in Romulus, New York. They hoped to stop the deployment of the Cruise and Pershing II missiles to Europe from that weapons depot.]

Michelle Crone was the one who was most responsible for combining culture and politics. Michelle was the “glue” that held us Rhythm Fest producers together. She’s the one who brought in Barbara Savage, Kathleen Mahoney, and me. She also involved her partner at the time, Susan Fuchs. Billie Herman came in later as a coproducer and bookkeeper. Michelle was really the core person.

They wanted to do one in the South for all the people who had been kicked out of all the other festivals, like Michigan [the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, aka MichFest] or Robin Tyler’s Southern Music & Comedy Festival in 1984. Because of my friendship with Michelle, she asked me to come on board. I hesitated, and I finally decided to do it. The six of us became the coproducers of Rhythm Fest.

RN: The Chapel Hill street was also the address for people to register for Rhythm Fest.

MC: Yes, that was a neat thing. We were able to use my office address and phone number. When I answered the phone I would say, “Hello, you have reached either Rhythm Fest or the War Resisters League.”

RN: I love those connections. You said that at the first Rhythm Fest, you had a workshop about the Harvey Gantt U.S. Senate Campaign, too. Rhythm Fest was really a cauldron for political activism.

MC: You know, it was one of those things where you just do what you do without realizing until later the impact it has. Remember that the Rhythm Fest slogan was “women, music, art, and politics,” just to show you how much we wanted to stir up the difference between us and all the other festivals. We had such interesting workshops of all kinds.

Several great things came out of Rhythm Fest, such as some funders later on for SONG, which we started in 1993. Rhythm Fest was a place where a lot of people now in SONG could go and do workshops. The kernels of what would become SONG began at Rhythm Fest.

Rhythm Fest came out of all the other festivals we’d been going to. Michelle and I knew each other from Albany, New York. She said to me, “I have an idea for starting a women’s music festival, and with politics involved. No one else is doing that.” She just got tired of the drama and trauma of some of the other festivals, and she said, “We want to start a new model: music, comedy, and politics.”

We put Rhythm Fest in the South, and because of adding the politics to the festival, that’s how I met Pam McMichael. I already knew Suzanne Pharr, and I think that’s how I met Joan Garner. All of them were SONG cofounders. Rhythm Fest was a place where a lot of people now in SONG could go and do workshops.

The way we got involved with Rhythm Fest, I was working with Dannia Southerland, a white lesbian with the War Resisters League’s Southeast office. We heard about the Women’s Peace Encampment in Seneca, New York. We decided to do a women’s peace walk from Durham, North Carolina, to the Seneca Peace Encampment, and that’s how I met Michelle Crone. That was in 1983.

Because of that peace encampment relationship; and because Dannia was from Albany and I’m from Albany, we kept in touch. The other Rhythm Fest producers had all done festivals before.

[In Seneca County, New York, this peace encampment ran from July 4 to Labor Day weekend, 1983. The protesters were camped near the Seneca Army Depot in Romulus, New York. They were trying to stop deployment of Cruise and Pershing II missiles to Europe from that weapons depot.]

Women’s Music Festivals: The Cultural Arm of Lesbian-Feminism

RN: After meeting Michelle Crone in 1983, when did you all get the idea for Rhythm Fest, and how long did it take you to find the land?

MC: By the late 1980s, Michelle had grown dissatisfied with the organization of women’s festivals. That’s why she contacted us about having a woman-only festival focused on the recognition of minority groups. I had never done a festival. I’ve never been to Michigan for the MichFest. I went to the Southern Women’s Music & Comedy Festival produced by Robin Tyler in 1984. That was the one I knew best.

Michelle was saying that it would be interesting to add politics. We didn’t have the politics in the other ones. The brainstorm for all that really came from Barbara Savage and Kathleen Mahoney.

The way I came to know Kathleen Mahoney was in the time before Melissa Etheridge was famous as Melissa Etheridge. Ladyslipper Music, here in Durham, which I worked for, and now serve on the board, was always bringing women performers into Durham. Laurie Fuchs of Ladyslipper wanted to take a break from women’s music festivals, and we created this thing called Real Women Productions.

It was myself, Cheri Sistek from the Duke Women’s Center, and Cris South. Our idea was to bring women musicians here, since Durham is kind of a hub. We got an email from a woman named Kathleen Mahoney who wanted to bring this singer, a woman with guitar, to Durham. We said the only venue we had was the YWCA in Durham. We asked, “What’s her name?” The singer’s name was Melissa Etheridge. We figured we could charge about $2.50 or $3.00. Who knew?

At that time, we had already started Rhythm Fest, and we were also using these networks to book musicians for Rhythm Fest. We brought her to the YMCA [a non-profit community organization] for a ticket price of about $2.50. And next year, she comes and she’s our headliner at Rhythm Fest.

I find all these links intriguing. I was just on a call with someone working on the 40th anniversary of the Richmond Lesbian Feminists (RLF). Michigan turns 40 this year. The National Women’s Music Festival turned 40 last year. This is the genesis of what became women’s music culture across the country.

I can tell you that Robin Tyler was not at all happy about Rhythm Fest, and we had a major battle with her. She felt like she owned the South and no one else should come in here. Michelle had worked for Robin Tyler, and I had known Robin for years when she invited me to do a workshop at Southern Music & Comedy Festival in 1984. But the second that Robin heard that there might be another festival in the South, even though we were doing it on a date that didn’t in any way compete with hers, she wouldn’t let us bring Rhythm Fest flyers to her Southern festival. Southern was on Memorial Day weekend, at the end of May, and Rhythm Fest was not until Labor Day weekend, months away.

Robin warned us, “If I see flyers on this land, I will throw you off the land.” Damned if she didn’t! I went to Southern, I paid my money, I brought my flyers, and I started hanging them out. You know, “question authority.” And her thugs came and threw me off the land.

Those producers had an attitude, you know, wristbands, VIP areas, etc. That attitude of Robin’s is why Michelle thought we needed another festival. We weren’t going to do any of that. We wanted to do a different culture, not like other festivals. We weren’t going to sit there and act like we had more power than anyone else. We were just like everyone else.

Michelle wanted to do a small festival with more content, more music, and add politics. The instant people knew we had it, people wanted to perform at Rhythm Fest. We booked acts that normally would not get into festivals. Robin Tyler told her vendors they couldn’t go anywhere else, or at least not to Rhythm Fest.

The first three times that we had Rhythm Fest we had it at Lookout Mountain, Georgia. For those three years, we were able to use land owned by two lesbians. The fourth year was in North Carolina, not far from Asheville. It was again in North Carolina in 1994. The last one was at a camp near Aiken, South Carolina, in 1995.

RN: What happened to stop it?

MC: Land. I mean, if you do not own land, it is so hard to find land to accommodate a certain number of women. It had to be land with toilets, and where everything was accessible. Robin Tyler, I think, rented a Girl Scout camp off-season, and her festival was a much bigger festival than we were doing.

RN: Wanda Henson and Brenda Henson bought land in Mississippi because they were having such trouble finding land for the Gulf Coast Festival. They and their land began to be the target of hate crimes. [See the Hensons’ story in Sinister Wisdom 98, fall 2015, pp. 142-45.]

MC: Yes, true. They went through a lot, but they persevered. They got a good number of lesbians coming and going all year helping them. There were obstacles for women to gather for a festival even when women did own the land.

RN: The Hensons had rented a Methodist camp for 1992, and lost the rental contract when the camp heard of plans for a Jewish Seder ritual at the festival. The Hensons had to switch to a Boy Scout camp, which had a lot of male caretakers, and was somewhat safer. Bonnie Morris wrote about it in her book, Eden Built by Eves (1999, page 222).

MC: The problem with renting land is you have to follow all the rules and regs that go with it.

We had to scramble for land every year. Michigan owns that land where MichFest is held. And they only use it a month out of the year. What do they do with it the rest of the year? Lesbians are now getting older and looking for places to retire. There’s a place in Arizona, and Olivia has a place where people are retiring. Michigan doesn’t seem to want it to be used other than for the festival.

RN: How did you, the Rhythm Fest producers, organize everything?

MC: One of the things we did was for each of the six producers to have a specific role. My role was preregistration and registration for all the volunteers, including all the paperwork we needed before people got on the land. Once on the land, I coordinated the people coming in, as well as their volunteer work shifts, and where they would bunk. You know, the logistics person.

Michelle and Kathleen booked the artists. Barbara Savage took care of the food and all of the meals on site. Billie Herman did all of the books. She is the one who would know how many came, what it cost us, the how many volunteers, how many vendors we had, etc.

Rhythm Fest featured special camping areas for all types of women with special needs: women over 40, disabled women, women with children, chemical free (free of fragrances and such), chemical tolerant, clean & sober, biker dykes, quiet women, and rowdy women.

We also had Ladyslipper coming to sell CDs. They helped us book talent, and they publicized it through their website, building a mailing list. Each of the producers could tell you a different story.

MC: When Michelle, I, and others were talking about adding politics to Rhythm Fest, we were talking about lesbian and gay politics. (The B, T, and other letters weren’t used at that time yet.)

That was 1990, a pivotal year. That was the first year North Carolina had a really organized a senate campaign to take on Jesse Helms, an extreme misogynist and white nationalist. Earlier in 1984, to oppose Helms, we had a vigorous campaign for then-incumbent, Democratic Governor Jim Hunt. Hunt was very much liked by both major parties, and favored to win. Hunt lost by only a slim margin. This new campaign was called North Carolina Senate Vote ‘90. I remember working on that and on Rhythm Fest at the same time.

One of the workshops at Rhythm Fest was focused on organizing to elect Harvey Gantt to defeat Jesse Helms. Carla Wallace and Pam McMichael came from Kentucky. They were interested in what they could do as Southerners to help with what was going on in North Carolina. Even though Helms got re-elected, that work we did in 1990 and the networks we created exist to this day. And that was thanks to Sue Hyde, from the Gay and Lesbian Task Force, who came to Durham in maybe 1989.

There was going to be a Durham City Council conversation about passing a non-discrimination ordinance, based on sexual orientation. Sue Hyde came down to testify at city hall, and we were all in the room, including members of the War Resisters League, etc. Afterward, she asked us what we were going to do to defeat Helms. We didn’t know. She said that we ought to do something, and that’s why we started organizations.

That one meeting became the center of what became North Carolina Senate Vote ‘90. It got national and international attention. It was the most incredible political organizing I had ever done pre-Obama. I had the good fortune to be Harvey Gantt’s campaign manager. I took a year off from Ladyslipper to do that. And we brought all that into Rhythm Fest in 1990. Amazing. From there, I joined the Human Rights Campaign and worked in Washington, D.C.

RN: Is there anything else you’d like to say about Rhythm Fest?

MC: People have to make these things happen. These women’s music festivals were about more than being on the land to hear people’s performances. This was a culture. Lesbians and others had to break through to make a career. If it hadn’t been for church basements and YMCAs, and for people making a way out of no way… you have to appreciate the way this is woven into the fabric of this country.

Melissa Etheridge breaking through, and that country singer who came out after Melissa: K.D. Lang. Some lesbian musicians didn’t even want to be in Ladyslipper because they weren’t out. They were worried about people thinking they were lesbian. They were lesbian! What the hell is that?

Before Lilith Fair, which started with some of the mainline performers, people like Sarah McLachlin, who was there before them? We were! I’m so struck by the importance of women’s culture in music and art and dance. We had to create venues for them out of nothing. This has been such a gift, and I feel so blessed to have been a part of that.

The other thing I thought was about the race and class issues around women’s music. Of course, the majority of women at festivals were white. Yet when I think about Sweet Honey in the Rock; Casselberry and Dupree; and the other performers who were women of color, I don’t know where we’d be if it hadn’t been for women’s culture and these festivals. They kind of led to “mainstream,” or had a pivotal role anyway. I feel humbled that we had a role to play.

Real Women Productions

RN: When did you leave Durham, North Carolina?

MC: What happened was that after the campaign, North Carolina Senate Vote ‘90, which was very high profile, I got a call from one of the board members of the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) Fund in 1991 or ’92, saying that they would love for me to take a job with them in Washington, D.C., based on the work I had done for North Carolina Senate Vote ‘90. And I took the job.

I was at the Human Rights Campaign Fund for three and a half years. It must have been 1992 to 1995. I came back to Durham, North Carolina, in 1995 to run the campaign for the second Gantt versus Helms race in 1996.

RN: When did you start Real Women Productions?

MC: That was before I left Durham to work for the HRC. Ladyslipper Music, by being here in Durham, and because of all the artists that they carried, produced many concerts in our city. Those women and lesbian artists would purposely put Durham on their tour because of Ladyslipper. Laurie Fuchs decided that Ladyslipper didn’t want to produce concerts for a while. That’s why a group of us started Real Women Productions. It was Cheri Sistek, Cris South, and myself who started that production company just to keep it all going as a sort of a placeholder while Ladyslipper took a break from it.

RN: Lucy Harris, who was later one of the Real Women producers, said that those concerts were fundraisers; and you always made money or broke even.

MC: Yes, that’s true. And the idea was not to make money for ourselves. Any money we made was donated to another organization, or maybe a group that cosponsored a concert. Also, the money was put back in to keep the company going. We did it for four or five years, 1986 to 1990.

After I left to go to D.C., Lucy and her partner took over, and they changed the name to Blue Moon Productions. Ours was never intended as anything other than something to fill in while Ladyslipper was on pause. It was a way to bring good acts into town.

Some of the fundraising we did with these concerts went for North Carolina Senate Vote ‘90. One of the acts we brought was Lea Delaria, who’s now on Orange is the New Black. Small world! Another time, we brought this young white woman with a guitar named Melissa Etheridge to play at the YMCA for an admission of something like $3.50. Who knew what would happen with that? There were some interesting “who knew?” stories, because we wanted to have some culture in Durham, North Carolina.

Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists (TALF): Durham Was a Hotbed of Lesbian-Feminist Activism

RN: Could you talk a little more about what made Durham such a hotbed of lesbian-feminist activism in those years?

MC: It was due to several things. Ladyslipper Music was there. It was not only because they existed as an organization, but also because a lot of people got their first jobs at Ladyslipper. People moved here because they had heard of Ladyslipper, and this was in the heyday of all those women’s music festivals. Of course, Ladyslipper had their catalog across the entire country and the world. Thus, people recognized Durham, North Carolina, because Ladyslipper was here. That had to be one of those anchors.

Another was Duke University. That’s where Mab Segrest came from. A lot of lesbian feminists at Duke were finding ways to do collaborations. Lesbians were coming here from all over as well. [Mab Segrest was in graduate school at Duke, working on her PhD in English. Minnie Bruce Pratt was in the PhD program at UNC Chapel Hill at that same time. Duke and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill are only 12 miles apart. It is hard to separate the influence of Duke and Chapel Hill though the city of Durham is much larger. Both communities had a lot of cross-pollination.]

Other anchors as to why this was happening here at that time would include our forming an organization called Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists (TALF). Feminary was here also, with Mab Segrest, Minnie Bruce Pratt, and several other lesbian writers. We just opened our first LGBTQ Center here in Durham last month. Durham has this reputation as a “hotbed of lesbian-feminist activism” to this day. [Feminary was the name of a collective that published a lesbian-feminist newsletter that became an important lesbian literary quarterly of the same name (1977-82). See Merril Mushroom, “Feminary: A Feminist Journal for the South Emphasizing the Lesbian Vision,” Sinister Wisdom 116 (Spring 2020): 133-36.]

RN: I interviewed eight lesbians when I visited Durham in July 2015. One thing that I noticed is that even though it’s very multicultural with all those universities, including North Carolina Central, a historically Black university, I wasn’t getting anything about African American people’s organizations or events.

MC: That had to be because of the people you talked to. Did you talk to any African American lesbians besides me?

RN: No, only you. Who else is someone I could interview?

MC: Let’s just put some cards on the table here. Even in San Francisco when I first moved there in 1969, there weren’t a whole lot of women of color coming into San Francisco because they already had this stuff in the East Bay. You had Black Lesbians and Latina Lesbians. Sometimes it’s geographical, and sometimes it’s cultural. To this day, in Durham, North Carolina, it’s mostly white lesbians that you’ll see organizing.

I can recommend that you talk to at least one other out Black lesbian I know: Helena Cragg. Helena is the one who was instrumental in the fact that we have our first ever LGBTQ Center of Durham. She’s on Facebook, and the LGBTQ Center is on Facebook, too.

There’s a reason why you have these culturally-rich,

Black pride events that celebrate our Blackness as well as our gayness.

One thing that’s happening is that there are so many pride celebrations. I was just in San Francisco, and their pride had something like 1.4 million people come to that thing. Yet that’s not how it started out. With the growing number of people of color coming out of the closet, there are now numerous Black Pride celebrations happening in the same cities, different dates. When we started our first Black Pride here in Durham, people wanted to know why we were starting that, since we already had a pride event. They were not saying, “We’re so happy for you,” or “We’re so glad.” People thought of it as a negative thing, as if we were competing with traditional white pride events. The reality is that we do both. It was the same way in Washington, D.C. Black pride was met with such hostility. Why? They finally realize that there’s more than enough pride to go around. And, frankly, this country’s population is becoming more of color, not less.

There’s a reason why you have these culturally-rich, Black pride events that celebrate our Blackness as well as our gayness. Some people would never set foot in a white pride parade, but they will come to a Black pride event. We’ve had Triangle Black Pride for quite some time. Now we have Triangle Shades of Pride because our communities of colors, plural, are growing, which reflects the diversity of the community. And we still go to the regular, (white) Durham pride celebrations, or at least, to parts of it.

North Carolina Central just had their second annual Lavender Graduation, because they had a straight ally over there who was so deeply committed to having a center for LGBT allies that they now have a full office with paid staff. That took ten years to make a reality. And that’s happening with other HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in the South. [Lavender graduation is honoring LGBTQ people who graduate.]

Yet many Black lesbians and gays are still in the closet, and they don’t want anyone to know. And here’s why. A lot of Black folk don’t have the money to move to San Francisco, New York, Chicago. And their families live here. They are more likely to come out in some other town, like Charlotte, where their families would not know. That’s just real.

There are times when it is important for us to be in our safe spaces

of who we are as a class, race, or whatever it might be.

RN: From what I can gather, Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists, TALF, was almost exclusively white.

MC: Almost the entire lesbian community here was phenomenally white. Part of what kept Black lesbians away was that they were in the closet, as I just mentioned. Part of it was… I don’t know quite how to say this. For example, TALF would always meet where white women would normally go. They would never go anywhere that was not like them. There were other opportunities, other groups that formed with people of color, and other Black lesbian groups that I was a part of. People just tend to stay with people who are like themselves and who go where they go. Think about it.

When somebody says, “We’re having a pride celebration,” you don’t think about it. You just go. But if somebody says, “We’re having a Black pride celebration,” you might wonder if you are welcome if you aren’t Black. One of the big mistakes that the Washington, D.C. Black Pride celebration made was that they assumed everyone knew they were welcome. Unless you specifically said, “Everyone Welcome,” people thought, out of respect, maybe they shouldn’t be there.

Now, I think there’s more a matter of understanding that we need more diverse groups in order to connect. Also, more people are out now. There’s also the dynamics of the communities of color. We have a large Latino/Latina community that’s out and gay, too. Triangle Shades of Pride is in its fifth or sixth year (before that it was Triangle Black Pride).

People of color wanted to have their own TALF, one that celebrated their own identity. I can’t remember the name of that organization. There’s also a social group where they play cards. There are two women who do an annual conference for the Black lesbian community. One time they tried to do it with the gay men.

I don’t think the South is unique in being “segregated” in this way. Part of it is an understanding of the importance of cultural identity. That’s why you have the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People], and La Raza [civil rights for Hispanic people]. That doesn’t preclude that people will also get together in a multiracial way. We definitely want to work together. However, there are times when it is important for us to be in our safe spaces, spaces of who we are as a class, race, or whatever the affinity might be.

I don’t want to give the impression that it’s segregated down here. It’s almost the opposite. Especially now that more and more people of color are advancing. We just elected our first, straight African American ally to the Durham City Council. She had the complete support of both our LGBT communities and our communities of color. That’s why she’s sitting on the Durham City Council; and there’s an important role for her to play there. That’s what happens when you have collaboration and cooperation. It’s not because we’re racially segregated, or segregated by class, or by rural versus urban.

El Centro Hispano has its own LGBT group here that would tap into the Latina lesbian community in Durham, and in other parts of the Triangle area.

RN: I guess it’s a positive form of separatism to have culturally similar groups.

MC: I wonder if there’s a more positive word than “separatism” for talking about what happens in urban areas like Durham. What about “affinity groups?

RN: Yes, affinity groups. Is this analogy true? The reason Black lesbians would want to have their own group is the same reason that lesbians in general want groups separate from gay men?

MC: That is probably more of a correlation. Also, remember that we want our own space, and it’s not an either/or situation. It’s a both/and. We want to be in collaboration with, cooperating with, partnering with people who are not like us. At the same time, we also need our own space. That’s how it goes from “me” to “we.” That’s a more positive way than thinking of it as segregating. Both/and; not either/or.

RN: There’s also the fact that the dominant culture here is white and male.

MC: For now. California is no longer white. It’s predominately people of color. However, people in leadership continue to be white folk. The question is whether we’re going to have adequate representation of the reality of the population, or if it’s going to be as it always has been. The codirector model used at SONG is more the shape of the future. That’s what’s so cool about it. Instead of a single executive with hierarchical management, the codirector model can be up to ten or fifteen people sharing power.

It’s the same thing with gay student alliances. Some start out all white or all Black. But if you start out as SONG did, with equal numbers of Black and white founders, executives, and board members, with it looking the way you want from the beginning, you are more likely to get there. We’re now in our twenty-third year, and that model still works. [SONG is still active in 2025, after thirty-two years .]

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Barbara Ester, “Women’s Music Festivals in the South,” Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017): 168-71.

“Mandy Carter, Scientist of Activism“, Duke University Library Exhibits.

Mandy Carter Papers (1970-2013), Real Women Production Series (1986-90), 4 boxes, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture, Duke University.

Michelle Crone Papers (1927-2000), University of Albany, SUNY.

Phyllis Free, “Southerners on New Ground (SONG) 1993-Present,” Sinister Wisdom 93 (Summer 2014): 119-26.

Rose Norman, “Robin Tyler and the Live and Let Live Southern Festival,” Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017): 178-81.

Rose Norman and Merril Mushroom, “Rhythm Fest: Women’s Music, Art & Politics (1990-95), Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017):188-95.