Lissa LeGrand and Magnolia Productions: Building Lesbian Community Through Music and the Arts in Birmingham, Alabama

Interview in Birmingham, Alabama, at the Birmingham Botanical Gardens by Rose Norman, June 23, 2015

About Activism

I hear the word ‘activist,’ and what comes to mind is people lying down in front of bulldozers, chaining themselves to fences, and sitting on top of hundred-foot-tall trees to keep out the loggers. I really don’t consider myself that kind of an activist. I’m a performer. My activism has taken the form of words and music as a writer, a songwriter, and a performer.

During the heyday of the civil rights era, my father held the title of City Editor of the Birmingham Post-Herald, which was Alabama’s second-largest, and liberal, newspaper. I was a little young to get the full impact of the civil rights era. I was only nine years old in 1963, when the 16th St. Baptist Church in my home town was bombed. The activism of those years sort of sank into my soul. I think in some ways, I wasn’t conscious of it. Papa became editor in chief in the late 1960s. Until his untimely death in 1978, he continued to speak out in his editorials for all human rights; and for equal opportunity, dignity, and justice for all, no exception. I was extremely proud of my father and his voice, always speaking out for women’s rights and civil rights across the board. I wish he were still with us.

My earliest activism was in the environmental front. That’s honestly where my home and heart of activism still is today. I feel as if I’ve come full circle. My years as an activist in the feminist and lesbian cultural milieu were formative, wonderful, and empowering. I don’t feel that I’ve left that in spirit, yet I do feel that I’ve left that in my life. And that’s a regret. But my life now is in dealing with the Earth and the damage we’ve done to it; how can we heal it, and how can we get the message out to people so that they will really understand the trauma. If we don’t save this Earth, we will not save ourselves. I like having my hands in the dirt. That’s my activism these days.

Biographical Note

I have always identified as a Southerner. I was born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama, going to school “up north” at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. I earned a degree in medieval and Renaissance history from Vanderbilt, in 1976.

While I have not always lived in the South, I spent two and a half years in Philadelphia, from 1978 to 1981; and in 1988 and 1989, I was on the road with a band called the Fabulous Dyketones. I spent 1990 and 1991 in Los Angeles, California. Other than that, I’ve pretty much been in my home town, Birmingham, Alabama.

From Environmental Activism to Feminist Activism and Magnolia Productions

I attended many women’s music festivals during the 1980s. I think 1981 was my first festival, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. How did I morph into feminist activism from environmentalist activism? I’ve always been someone who wanted to be outside, climbing trees and all of that. I sort of submerged that during the 1980s to really focus on and put my energy into lifting women up and giving women performers a chance. That’s really what Magnolia Productions was about, giving female performers a chance to do things on stage and behind the scenes, things they were traditionally not doing, or not being encouraged to do before.

My environmental activist side has never gone away. It’s just that for a number of years, feminist activism took precedence. I feel as if I’m coming home now, coming back these last fifteen years or so, to farming, studying, research, and growing things.

Magnolia Productions

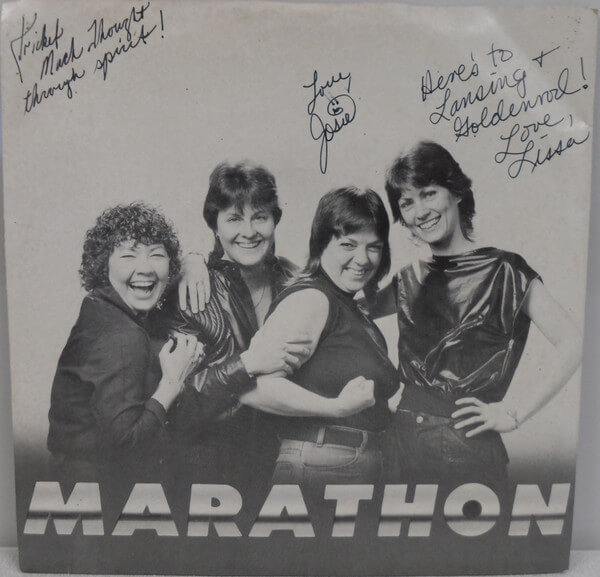

Magnolia Productions was a collective of more than twenty Birmingham [Alabama] lesbians, more than half of them performers, who produced over twenty-five women’s events in Birmingham between 1982 and 1987. We produced local musicians, as well as bringing in major performers like: Robin Flower, April 1983 and April 1986; June Millington, October 1983 and April 1985; Margie Adam, March 1984; Meg Christian, April 1984; Cris Williamson and Tret Fure, November 1984; Casselberry & Dupree, February 1985; Holly Near, April 1987; and many others. We also brought in lesbian writers, such as Minnie Bruce Pratt, November 1983; and storyteller Louise Kessel, January 1986.

To fund these shows, our local performers, most of them members of the Magnolia Productions collective, gave concerts. Donations from these concerts help fund the big shows. This included at least five “Magnolia Jams,” the variety shows that featured many local performers.

A lot of groundwork was being laid for that before I returned to Birmingham from Philadelphia [Pennsylvania] in 1981, like the organization, Third Thursday. My understanding is that Third Thursday was a group of women, not all of them lesbians; and those lesbians were very closeted. It had a lot of women professionals, such as doctors and lawyers and such. They were very political, members of Alabama’s state chapter of the National Organization for Women, and Alabama Women’s Political Caucus. They were doing a lot of political activism around the women’s movement. They met for drinks on third Thursdays after work.

It was right around the time that I came back to Birmingham in 1981 when women were splintering off from that group. They wanted to have a totally lesbian group. That’s how the organization, Second Sundays, was born. It was a monthly potluck, and a strictly social way for women to get together in a safe space without having to be in the bars. That was the thing about Second Sundays. We wanted everybody to know it was safe space, and that what happened at Second Sundays stayed there. It was confidential. No one would out anybody from having seen them at Second Sundays.

Out of the social component of Second Sundays, there arose a compelling need to do something, to give back to the community. We wanted a project.

Before that, I had been away at college, doing summer stock theater from 1972 to 1976. I was not really aware of any women’s community in Birmingham during that time. I returned to Birmingham in 1976 due to my father’s illness, and I left again a few months after his death in 1978. By then, I had connected with a lesbian microcommunity within the city’s theater scene. I still saw no sign of the women’s community that was to blossom over the next two or three years. I moved to Philadelphia [Pennsylvania] in 1978 to pursue a theater career, soon learning what a lesbian community in “the big city” could really be. I also discovered the women’s music scene there, getting familiar with a number of artists through their concerts in Philadelphia. When I came back to Birmingham in 1981, I was delighted to find that we had a strong and growing community here.

When I got back, two other women had just moved to Birmingham from Baltimore [Maryland] and Atlanta [Georgia], Joy Godsey and another woman musician. Joy had been in Atlanta a few years. The other woman musician is from Baltimore or somewhere around there, who had gotten a job with one of the television stations down here in Birmingham. All three of us arrived the same time from big cities with blossoming women’s music scenes. We were aware of how large the women’s music scene was. I think we had a larger sense of its vigorousness than Birmingham women did at that time. This is not to imply that Birmingham women didn’t know about Margie Adam or Meg Christian. I think the three of us brought a larger sense of all of that women’s music scene to Birmingham.

We got a lot of women excited about this at Second Sundays. We were sharing our record albums. One of our founding band members was an active part of that. She was a great guitar player—still is—and singer; and she played a lot of those songs. She would do impromptu concerts in the living room at Second Sundays, and Joy did, too, playing songs by Willie Tyson [a woman], Meg Christian, Cris Williamson, and Holly Near. Everybody was loving it, and they wanted more of it. Out of the social component of Second Sundays, there arose a compelling need to do something, to give back to the community. We wanted a project.

My strength then came from feeling such an integral part of a group. The power and energy of the group empowered us all individually. I didn’t myself feel so much like an individual activist, yet I felt empowered and strong in being part of a group.

Three ideas were tossed around, and I can only remember two of them. One was to have a softball team. A lot of women were interested, and there was a softball league. Another was to form a production company to bring women’s music artists to Birmingham. When I sat down to make a list of the people who were the most active members of the Magnolia Women’s Music Collective, Magnolia Productions, I was shocked to see that many more than half of us were performers. That spoke to our need to have a forum for ourselves to give back to the community. Also, to form a production team that would bring in the national artists, and expose our community to Robin Flower and Deidre McCalla; Casselberry & Dupree; June Millington; and all of these other wonderful artists.

[Magnolia Productions brought all of these artists, and several more, to Birmingham between 1983 and 1987. See chronological list at the end of this interview.].

It’s been really good to think back on all that excitement and energy. It was a very heady time. I remember being passionate and very motivated to getting this message out. And we had strong support from the community, including strong support from a certain segment of the straight community, as well. We had a lot of support from men, who were allowed to come to the concerts, mainly the concerts of local performers, not so much to hear Meg Christian or Margie Adam. When my band, Marathon, got started, we had excellent support from the straight community, men and women; and of course, the lesbian community. It was a nice kind of an “all-in” feeling. I don’t remember any hate stuff going on. Nobody ever threw an egg on the door of the bar where we were playing. It was a very exciting time. My strength then came from feeling such an integral part of a group. The power and energy of the group empowered us all individually. I didn’t myself feel so much like an individual activist, yet I felt empowered and strong in being part of a group. And I’ll take ownership as being a leader in that group. “A” leader, not by any means “the” leader of the group. It was very much a group effort.

You had asked how we divided up the work for Magnolia Productions. We were all politically correct, and we voted on everything. Once we voted on things, the desire to do the music won pretty handily, even over the softball, mainly because we knew that music was something that more of the community could attend and be participants. It would reach a lot more people than the softball would. There was a softball crowd who stuck to just softball and the bars. We were trying to open things up to a wider consciousness. We were all fine with bars and softball. We wanted to add more choices to it.

There was a fairly large number of lesbians that we knew and recognized as family, who we also knew to be closeted. Most of them did not come to Second Sundays except every now and then. They were the older crowd, who had retired, and who wanted to spend their time at the lake. However, they were very supportive of us. It’s interesting how many different factions of the lesbian community that we reached. Younger dykes were coming to our concerts. Older folks would appear and cheer wildly for the artists. The, they would disappear into the night, carefully and quietly. We felt a lot of support. I think that was pretty remarkable, especially if you look at the atmosphere now, with so much hate and intolerance. It’s almost as if we’ve gone backwards.

Everything that could possibly be done to facilitate women getting to come to these concerts and to hear these messages, we did it. Everything. We tried to achieve that.

Once we decided to do concert productions, it was generally voted on by all of us. The work was divided up, and it all just fell into place. We asked who wanted to do what. People would just say that they liked to work sound equipment, or even, “I want to learn about sound equipment.” We were able to dig up a few folks who did know something about it. For the really big concerts, where we knew that the artists would be pretty demanding. We needed somebody who for sure knew what they were doing, and we would call Janet Snyder, in Atlanta [Georgia]. She may have worked with Orchid Productions. She was a great sound engineer, and she did most of our big concerts. Nancy Beatty and June Holloway did lights. Nancy, I think, hated going to meetings of any kind. She would come and do an excellent job. Then, she’d go away until the next event. She was sort of a one-of-a-kind in that department. Most of us were involved daily in all that we had going on in the forefront of our hearts and brains.

We were trying really hard to be politically correct. Those of us who had lived in larger cities had been to concerts where they had interpreters in American Sign Language (ASL) on the stage, where they were careful to have accessibility for differently-abled people, where they would always have child care. Everything that could possibly be done to facilitate women getting to come to these concerts and to hear these messages. Everything. We tried to do that. Mindy Norton, I think, did our ASL interpretation. The ASL interpreter was wonderful. She sign-interpreted almost all of our concerts though she was not an integral member of Magnolia Productions. She was not gay, yet she was happy to sign for us.

Magnolia Finances

You asked what I knew about the finances, and the answer is, “not much,” except that I played a lot for free to raise money to bring in the larger artists. We all did. That was how we got money in the first place: by playing concerts that brought in money, in order to then, bring in the larger artists. Debbie Diehl and probably, Sally Kopp, Marty Billingsley, and Joy Godsey would know more about that. Eventually, we did get 501(c)(3) nonprofit status. Kathy Johnson, an attorney and wonderful friend to the community, set that up for us.

As far as the dissolution of the group, when it finally did fizzle out, I don’t really know if there was any money left at the end. Maybe when we realized it was going to be our last event, we just used up all the money we had. I can’t imagine there would have been much. Our finances were not big at all.

Rose Norman: Maybe because you weren’t having to pay for expensive venues, you weren’t at financial risk as much as Lucina’s Orchid productions in Atlanta. My recollection of that interview is that they had a lot of trouble breaking even. There was a lot of negativity associated with that.

Lissa LeGrand: My part in the money was just trying to do the work to raise it. I’m not sure what happened to it after we paid the performers. Debbie Diehl might know more. My impression was that we were pretty even as to income and expenses. We operated from one event to the next. We figured out how much money that we needed, and then, whoever who was willing to do a concert would try to raise, hopefully, $200. That’s why we held our Magnolia Jams.

Magnolia Jams and Marathon

RN: Tell us more about the Magnolia Jams.

LL: When we made the commitment to form Magnolia Productions, and to bring in national artists, we recognized that we were going to have to have some money to do this. We decided to have a series of three concerts with local people performing that summer. I volunteered to do the first one. I did two nights of original music at Apple Bookstore, a wonderful, intimate space, the perfect place to do a concert. I got several members of Magnolia to sit in with me, or to sing harmony on a song. Kay played flute for me on a couple of tunes. That kicked it off. The next time was the first, “true” Magnolia Jam, a smorgasbord of all of us. I don’t remember playing for that one, where we had seven or eight women performing, some of them doing original music, and others doing covers of women’s music. Later, we had jams in places where there was room. Our singer-guitarist did the third concert.

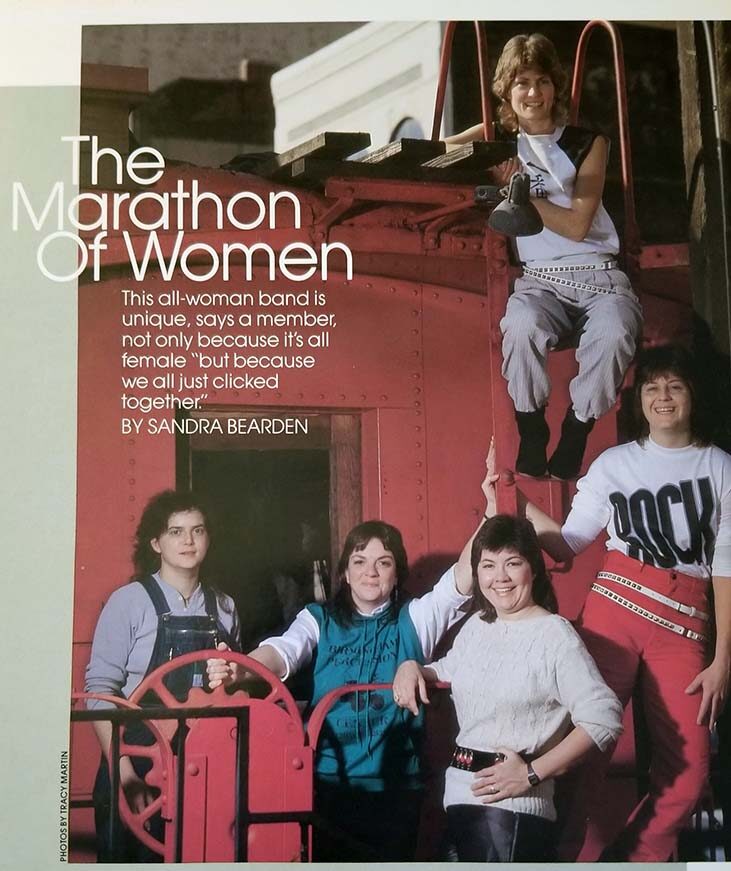

Marathon began when a local, professional singer and songwriter, who had been singing with bands around Birmingham for quite a while, and I had gotten together as a duo. She was a closeted lesbian. We were the first two members of Marathon, and she was our lead singer for the first half of Marathon’s existence.

We were joined after a year or so by Josie Grable on electric guitar, when she moved here from Bradenton Beach, Florida; and Josie has come to Second Sundays. Regina Cates moved here from Columbia, Missouri, and she played drums. We only learned years later that Regina’s first instrument was the French horn. She actually played French horn on occasion with the band. It’s a pretty neat trick to have your drummer pick up a French horn. Regina had picked up drums in short order, doing a really good job. We all jelled into a nice band, and we had an awful lot of fun.

We featured our lead singer in a double-bill concert that was held in a bigger space: a nice church on the campus of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, often used as a performance space. Reggie, Josie, and I played a little bit with our lead singer during that concert. That concert, combined with the money from the previous three concerts, gave us enough money to bring Robin Flower and her band to Birmingham the next spring. That was the first, real, Magnolia Productions women’s music concert on April 30, 1983.

After our three summer concerts, we moved up a notch, and we brought Jan Riley from Atlanta. Georgia. She is a professional singer and songwriter, who had done a double bill with another one of our Magnolia Productions founding members. She was a natural fit for being front person and lead singer for the band.

Just a side note. One reason I took up bass guitar was that I wanted an all-woman band, a real band, and not just a group of people playing guitars. I looked around, and saw that everybody played acoustic guitar. I realized somebody had to do something different, and I’m glad I did. I still play bass today, and I love it. It was nice to learn on the job.

RN: Have you always worked three jobs as you do today? You mentioned that you work for 90.3 WBHM, for your company, LSL Event Design, and that you also perform from time to time. You also farm, and that would make four jobs in all.

LL: It kind of feels like it! Variety is the spice of life. Actually, during that time, I was just working at the radio station WBHM, a National Public Radio station. I announced classical music and hosted “All Things Considered.” I’ve been associated with that station off and on for so long, doing so many things on air and hosting different shows. But I was doing just that as my way to make a living during those times. That’s how I could put all of my free time into Magnolia Productions and our band, Marathon.

RN: Did you say that Magnolia Productions grew out of the band, Marathon, or did Marathon grow out of Magnolia?

LL: As Magnolia Productions was starting as a women’s music collective, before we were “officially” a production company, I was learning to play bass guitar, when another musician and I were doing work as a duo. I had met this other woman musician at Second Sundays. We hit it off really well, and we started playing together, calling ourselves Marathon. That was at the same time as Magnolia was forming. In future Second Sundays, as Josie and Reggie arrived in town, we got to know them, too. We realized that we really could be a band. Marathon was really “born” out of Second Sundays, and we were already really involved in Magnolia Productions.

RN: Tell us about Holly Near and what Magnolia paid performing artists.

LL: Yes, I remember that Holly Near signed an album for me, and I think she put the date on it. She came in April of 1987. Her concert was really close to my birthday [April 16], and she may have written Happy Birthday when she signed the album.

I remember that when we first started, Holly Near was one of the first artists we looked at, which makes me laugh thinking about it now. I was working at the radio station, WBHM, and I had dropped the needle on a Beethoven quartet. That gave me 28 minutes to talk to somebody in California. I talked to Holly Near’s manager, who told me that her fee was $1,500. I gasped. There was no way that could we afford that. Her manager kept saying, “That’s a very reasonable fee.” I tried to explain that we would be lucky to get a hundred people at the concert, and they would not pay more than five dollars per person. We went around and around about it until it became obvious that we couldn’t work out anything.

I encountered Holly Near several times later at music festivals around the country, and she was very nice. She did express interest in coming to Birmingham, and we did finally bring her. We must have partnered with somebody else to put her at the Alabama Theatre. The Alabama chapter of NOW, maybe.

RN: The Magnolia Productions list shows that the Meg Christian concert was for the 9th Annual Southeastern Conference of Lesbians and Gay Men on April 14, 1984.

LL: Meg Christian was the other concert that I was going to say we partnered with another organization like Alabama NOW. We held it at the Parliament House on 20th Street in Birmingham. She came with Diane Lindsay. They may have been on tour. Magnolia Productions certainly participated in that. We probably could not have pulled that off and paid them all by ourselves. I’m guessing we did partner with somebody else. I don’t have any idea what we paid Holly when she did come.

RN: Do you remember what you paid Meg Christian?

LL: I really don’t know. We were paying $350 to $500, maybe. I’m sure we paid Meg Christian more than that. Some of the artists were giving us a cut rate because they were on tour, and they would have played a big gig in Atlanta. With Birmingham being only two hours away, they could often add us to their tours for less money than usual. Most of these artists were content to stay with us, in our homes, which was really ideal. Most of them seemed to enjoy that. We certainly did. June Millington stayed at our house several times. She is one of a kind, really amazing. She’s a night owl. She often stayed up all night and slept till noon. One time, I had to warn her about not going out walking alone really late at night. She wanted to walk from our house down to Birmingham’s Five Points area at 3:00 am. It’s not very far to walk; but it’s not safe to walk alone in that neighborhood at that hour.

RN: Was anything open in Birmingham at 3:00 am?

LL: She wouldn’t have cared. She was just walking, seeing the sights, whatever.

Kay and Bootsie

LL: Bootsie and her partner, Kay, now Kay Virago, were integral parts of Magnolia Productions. Kay was then Kay Crutcher, from the Crutcher bookstore family. Bootsie was one of the founding members. Kay and Bootsie were an interesting couple. Bootsie was older than Kay by maybe 20 or 25 years.

They were awesome. I remember that they were the most careful of all to try to keep us politically correct. I know that’s become a dirty word these days. People like to throw “politically correct” in your face, and it can be taken too far. It can get ridiculous. Then, it was very important to them to keep a pure feminist ethic, and to keep feminism and lesbianism in its purest form at the forefront of everything that we did. I appreciated that. That certainly doesn’t imply that any of us were of the man-hating variety of lesbians. We had a lot of really strong support from men in our community. Dan Gainey, a really good sound engineer, still in business here in Birmingham, was so kind to us. He was helpful when we had questions about running sound. He would loan us equipment, that sort of thing.

Bootsie was sort of like the Magnolia Mama, in a way. She was a very maternal figure, and she did have children of her own. She had not had an easy life. She was a survivor of a lot of trouble, difficult relationships, death. She was just such a good-hearted woman, such a radiant, positive soul.

Bootsie was the sane person. Kay would get a little volatile from time to time, keeping us on the straight and narrow stuff. Bootsie would calm everything down, explaining why we needed to do things, making us all feel heard. She was a very stabilizing force in the group, gentle and wise. And she had a lot of life experience under her belt.

She had that little grocery store, Bootsie’s Bohemiam, where the store Rojo is now. She had a little performance space there and a piano. Suzanne Ray gave a concert one night, one of our local artists.

Bootsie also brought in Alix Dobkin, and I missed that one. I think maybe I was no longer in town at that point.

I’m trying to think of jobs Bootsie took on. Some of us rotated jobs. Folks who did sound and lights, those were kind of fixed jobs. Those folks always welcomed an extra pair of hands. And everybody was always willing to come in to clean the hall and to carry in the equipment.

I took it on myself to approach the chair of the Music Department about using their recital hall for our concerts. Somehow, I managed to negotiate with him without ever mentioning that this was lesbian music, just women playing music, giving back to the community.

Most of our events were held at Hulsey Hall at the University of Alabama in Birmingham (UAB), which was a brand-new facility at the time. Since I worked at the WBHM radio station at UAB then, I took it on myself to approach the chair of the Music Department about using their recital hall for our concerts. Somehow, I managed to negotiate with him without ever mentioning that this was lesbian music, just women playing music, giving back to the community. After all, wasn’t Hulsey Hall built for the express purpose of giving recitals for the community? As far as I know, no money changed hands. Whether that had to do with my approaching him as a member of the UAB community, I don’t know. We were really lucky to have that space. It seated 190 people, yet it was an intimate space. We always had it pretty packed full. It was just right, really. Because if we’d had to rent a concert hall, we’d have gone in the hole at the first concert, and that would have been that.

Bootsie was more often than not our emcee, and everybody really enjoyed her. She wasn’t exactly what you would call a professional emcee. She was just so charming, personable, funny, and self-deprecating in a sweet and gentle way that people just loved her. Kay was a really fabulous flautist. She was a performer, also. She sang and played flute for various ones of us who had written a song that needed a flute.

Somebody in the Department of Women’s Studies at Birmingham-Southern College [Birmingham, Alabama] called me. I was sort of a network person. I seemed to be able to connect people who needed connecting, professionally or otherwise. People would call me for stuff, and I could tell them who to go to. They were having a Women’s Studies Program during their January interim term at Birmingham-Southern College, before spring term began, and they wanted to cap it off with a gala concert.

My band was kind of in flux at that point. Our lead singer had moved away. We were just getting acquainted with Carol Griffin, who became our second lead singer. The college wanted a band, and I gathered a bunch of performers, including a dancer, Sylvia Toffel aka Sycamore. Also, a unnamed founding member; plus Joy Godsey, Sherry Atkinson, and the remaining members of Marathon: Regina Cates on drums, Josie Grable on guitar, and me on bass. We backed up for everybody who wanted back-up. And we had a really terrific concert. By 1986, Carol Griffin was entrenched in the band, and we played at Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. That concert at Birmingham-Southern College must have been 1985; and it was Marathon and Friends that produced it. It was not a Magnolia Productions event.

Marching on Washington, D.C.

RN: If you have pictures of your band playing at Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival or at the March on Washington [D.C.] for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation in 1993, I would love to have those, as well as any other photos of Alabama lesbian musicians in a political setting.

LL: My then-partner, Josie Grable, and I played on the MichFest main stage at the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation in 1993, with Harry Wingfield, who was well known in Birmingham’s gay community as a talented singer-songwriter. I think Josie and I flew up in 1993, and we met Harry Wingfield, who was a major AIDS activist, and who was living with HIV. He was invited to perform at that march. He asked Josie and me to back him up. That was fun. We played three or four songs. It was packed like sardines. Everybody played microscopic sets. There were so many performers. He has moved away from Birmingham since then.

RN: When did it all end, and why?

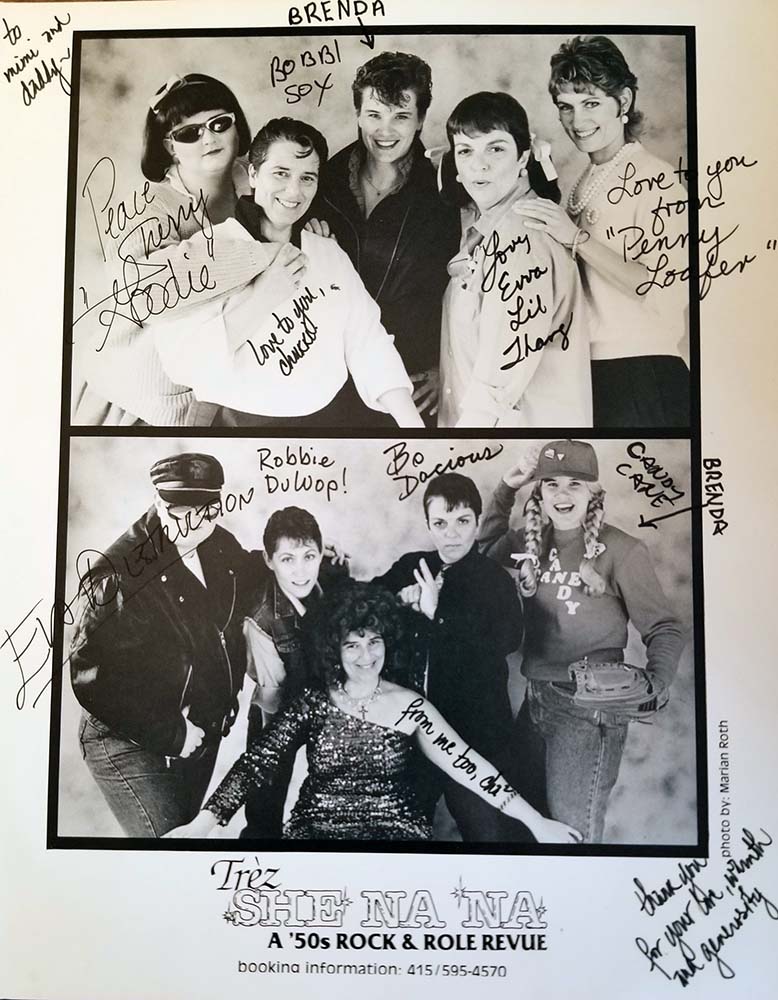

LL: I think there was a 1987 jam, maybe. Marathon did its last performance for the Alabama state convention for the National Organization for Women in the fall of 1987. We had morphed into The Janes. We were trying to branch out commercially, and to be the all-female rock band that could actually play at fraternity parties and be accepted. Did we really want that life? I don’t know. It ended up not working. After a few months of going that route, we had decided to call it quits, but we played that last concert in the fall of 1987. The next spring, Josie and I got the call from the Dyketones to go to Provincetown [Massachusetts]. That’s when I left. Effectively, I was not back in Birmingham until 1991. I was either on the road with the bands, or just in and out briefly. Not back enough to have any real part in the community.

When Josie and I came back in 1991 to live in Birmingham, we had one final, and maybe “the” final, meeting of Second Sundays at our house. We were all excited about having it. I know I had something to do that day; maybe it was to do a quick shift at the radio station that afternoon. This is when I knew it was really all over and done.

At our house, there came a few of the old folks from Magnolia Productions and Second Sundays, but there were hordes who came. There must have been seventy-five people in my house, fifty of whom I had never seen before, and forty of whom were under the age of 25. They brought beer and smoked cigarettes in the hot tub, trashing the place. The event had started at noon or 1:00 pm, and we expected people to be leaving by 4:00 or 5:00 pm. I came back at 7:00 pm, and Josie told me that they had been going out for beer and coming back. We finally had to tell them, “OK, everybody out! This is over. Thank you for coming. Hope you had a good time. Sorry that we didn’t get to meet you.”

It was the absolute antithesis of everything Second Sundays had originally been. I was so shocked by the disrespect of coming into the home of someone you don’t even know, and acting this way. I was absolutely stunned, and I was so disheartened. I knew this was not anything that I was going to try to continue if this was what it had come to. Bootsie, Kay, Joy, others came and stayed a couple of hours, saw how it was going, and left.

It was like an earthquake, and the earthquake was AIDS.

I think that event speaks to what was happening at the time, and why it all ended. Magnolia productions began to fizzle, and Lodestar was failing. It was like an earthquake, and the earthquake was AIDS. Everybody’s time, attention, energy, and focus were suddenly on the guys in a very personal way. How could we help these friends that we know and love, and who are dying right and left? How can we ease their transition? How can we stop this disease? How can we turn to political activism, rather than the more social and cultural activism that we had been doing? From then on, it was all focused on AIDS and on the guys. That’s where everybody’s energy, time, and money were going.

There didn’t seem to be many younger dykes coming into this community who wanted to do the kind of concerts that we had been doing. When we would put out a call for who wanted to help at the last few concerts, we didn’t get any new blood. It was just all of us who had been doing it for four years, and loving it, always happy to do it. But we were always looking for new people.

I think the music at that time was beginning to change, and the younger people were looking for something different. I don’t think they were putting much effort into getting what they were looking for. Maybe it’s kind of harsh to say that. I wasn’t around much, and I didn’t get to know them much. Maybe it’s unfair of me to say that. But my impression was that there was a turning of the tide, one toward the AIDS crisis, and the other, the younger women, who were turning back toward the bars and softball.

And this magical time just dissolved. That’s the wild thing. In my memory, looking back on that last year, it was like a wave that had come to the shore, a wave that was sinking and spreading out thinner and thinner into the sand… and then it was gone.

Also, one of our goals was to open this up to the community in as gentle a way as we could to let in folks beyond our little lesbian community, to say to people, “Don’t be afraid of this. This is artistic expression, and it needs to come out. It’s not going to hurt you, it’s not harmful, and you may find things you really enjoy here. Come and be with us at our concerts, come see what this is all about.” It’s in a non-threatening way. We were empowering people who have not had the chance to do these things, historically. It was a magical time, and I think we were aware of it at that time. Sometimes in a big movement, people are so focused on their own actions within the movement that they may not be aware of how special and magical the time is in the big picture of things. But I think that most of us had a sense of it being something very special though I don’t think we had a sense that it would end. I didn’t think that it would ever end. I was pretty shocked and surprised when I realized that it was ending.

And this magical time just dissolved. That’s the wild thing. In my memory, looking back on that last year, it was like a wave that had come to the shore, a wave that was sinking and spreading out thinner and thinner into the sand… and then it was gone.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.