Laurel Ferejohn: Building Lesbian Community

Interview at Laurel’s home, in Durham, North Carolina, by Rose Norman on July 12, 2015

Not Being Southern

You asked whether I consider myself a Southerner. I’ve lived here since 1983, in Durham, North Carolina. That’s a good long while, over 30 years. I’m from California. Although I very much consider Durham my home, I don’t consider myself a Southerner. I was born and raised in the Los Angeles County area, went to school in California, and graduated from the University of California at Irvine. During all of those formative years, I didn’t have even a whiff of Southern culture. I am a Durhamite now, yet I don’t think I can consider myself a Southerner.

When I moved out here in 1983, I came with my then husband. He was–and still is–on faculty at Duke University [in Durham, North Carolina]. After about three years, we separated. I had some choices to make about where to live, whether to move anywhere else.

Durham, North Carolina’s Lesbian-Feminist Community and The Newsletter

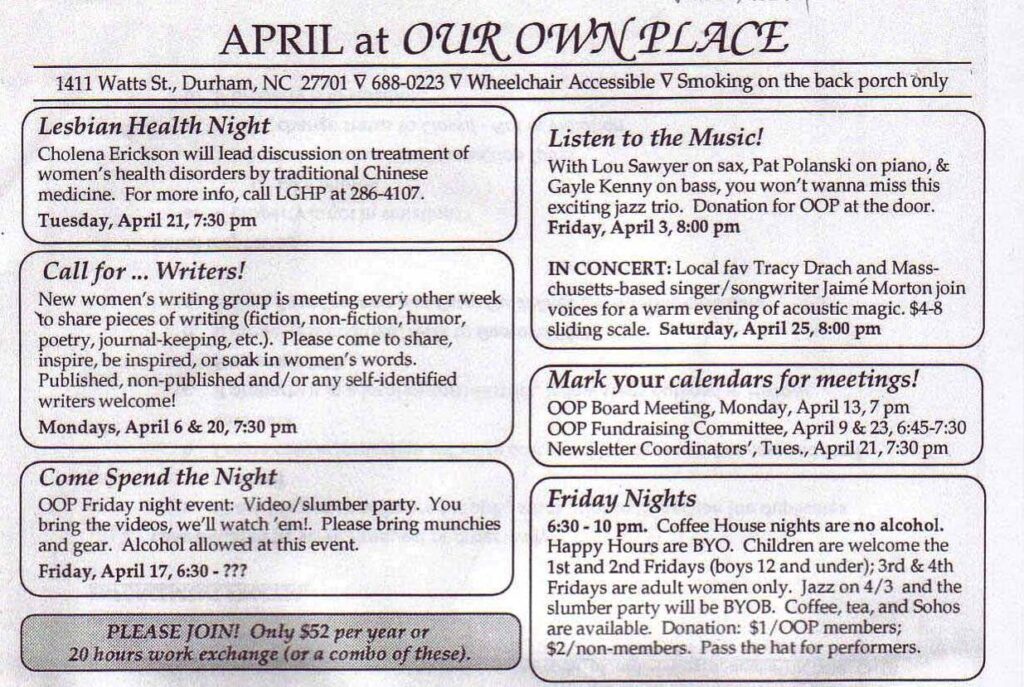

Around that time, some friends clued me in to the lesbian-feminist community here in Durham, which was really exciting to me. It was a vital community, mostly underground, and very organized in some ways. The Newsletter was a publication going at the time, very well established, with a mailing list of, I believe, more than 500 women, which would nearly double over the next five years. It was published and mailed twice a month: a monthly issue with articles contributed mainly by readers, along with some news items too. The monthly version also had a calendar, and then we produced a mid-month calendar. It was a great way to get the word out about any activity, whether it was an activist event or a cultural event.

Any organization that aligned with our vision, nonsexist and nonracist, could use the Newsletter to communicate to the women in the lesbian-feminist community. That was kind of thrilling to me, the community-building and community-supporting mission. The first thing I did was get on the Newsletter committee. I worked on The Newsletter for the next five years [1986 to 1991]. It was essential to everything else I did.

What I’d like to focus on today is the synergy between that publication, other organizations, and in terms of my own experience, really, any activism I did. All of that overlapped and intertwined with The Newsletter for much greater effectiveness than would have been possible otherwise. And I’ll particularly focus on Our Own Place.

Biographical Note

Laurel Ferejohn has lived in Durham, North Carolina, since 1983, after spending her first thirty-three years based in Los Angeles County. She came to Durham with her then husband [who was on faculty at Duke University]. When they divorced three years later, Laurel stayed in Durham, and with the help of friends, discovered Durham’s lesbian-feminist community. She came out that year, in 1986, and immediately volunteered on The Newsletter, an experience she wrote about for Sinister Wisdom (Spring 2022).

A believer in the power of community-oriented periodicals, she continued with that vital, underground, lesbian publication until she moved temporarily to the Asheville, North Carolina area in 1991. From 1989 to 1991, Ferejohn was a board member of Our Own Place, lesbian space in Durham. She was in charge of fundraising and publicity for programs and events during the first year, successfully rewriting the existing application for 501(c)(3) status, which had been denied until then.

Our Own Place (OOP)

I have my collection here from The Newsletter. It’s spotty, there are some missing issues, and have marked places where Our Own Place is mentioned. Reading through those was a great way to begin to remember what happened during those years. I’ve made copies for you of all those marked pages. [See links to OOP stories in The Newsletter and to Newsletter stories about AIDS-related civil disobedience, and confronting local news gatekeepers.]

With Our Own Place, what had already happened was that a group of women had been fundraising for space for five years. They were having trouble meeting their goal. Very few women had purchased memberships, a major part of the plan. My take on it was kind of chicken-and-egg, that memberships to Our Own Place would pick up once there was a place. I made the case, and other people felt sympathetic with that point of view. We decided to move forward even though the envisioned critical mass of money was not there.

Then it all happened so fast! I had been involved with the organization for a very short time when I found a space, only a block from where I lived on Watts St. in Durham. This was pretty central, and I talked everybody into it. That’s my recollection of it, for better or worse. It might have worked out better if we hadn’t done this, if we had instead found ways to ramp up fundraising. But we went ahead and leased the place, opening as soon as we could.

I became a board member of Our Own Place, in charge of fundraising, which was appropriate since I was the one who had led everyone down this path. Fundraising was going to be the hardest part of it. I did that for quite a while. I got involved in summer 1989, and we signed the lease in October 1989.We had our first OOP membership meeting there on November 15, and after we’d done some renovations,we had a grand opening party there on March 10, 1990.

[See “A Woman’s Place Is… Our Own Place, The Newsletter, vol. 9, no. 2, November 1989, p. 3.]

The rent was $725 a month plus utilities, supplies, and insurance. It was my job to raise about $1,100 a month for the space, and let me say, it was daunting. We constantly asked for memberships to be purchased, now that there was a space. That did get rolling somewhat. Also, there were constant events, and constant other fundraisers, like raffles. Musicians came, and people paid a door charge to listen to music. And we had some big events: multiple musical acts, comedians, storytellers, you name it. We had discussion groups where people were asked to make a donation. We had workshops, lectures, everything we could think of in that space.

We also made Our Own Place available for meetings and events by other lesbian-feminist organizations. All of that put together kept the doors open for quite a while. However, it was exhausting for everyone, especially those of us on the fundraising committee. It did not take flight in the way that I had envisioned, or that anyone else on the board had hoped, in terms of people purchasing memberships. If we had had 400 or 450 women purchase memberships that first year, it would have been very different. We wouldn’t have had to run ourselves ragged with the fundraising.But my build-it-and-they-will-come position bore fruit only in attendees and not so much in dollars.

Lucy Harris wrote a newsletter story stating that membership in November 1990 cost $52.00 a year, and that OOP had 100 members, which she wanted to triple by December. By November 1991, it had 163 members.

There had been an application for 501(c)(3) nonprofit status sometime before I got involved. No one had heard anything, and it had turned out that it was dead in the water because the person at the office in Washington, DC told me that there wasn’t enough information. There were no activities listed in the application, and the purpose of OOP wasn’t fleshed out. That wasn’t surprising since the space didn’t exist at the time the application went in. That’s why I rewrote that application since we now had all kinds of activities happening. We got approved for nonprofit status in June of 1991, shortly before I left the Triangle and the organization.

What also happened before that, in May 1990, was that Lucy Harris had approached me about taking on the position of executive director of Our Own Place. She wanted to do the job, raising the funds to keep it open and to pay her salary. I took that to the board, and they thought that there were possibilities there. I had a full-time job outside of Our Own Place. I thought that maybe if we had a full-time fundraiser, it would make it all work. Lucy Harris was very well connected, and she had done fundraising for a number of different projects. We thought she was worth a try. I believe that she came on first as a volunteer, and then, after a certain number of months, maybe four months, the board would put her under contract as an employee. That happened in October 1990, I believe. Or it could have been that she started volunteering in October. The Newsletter says she started then, but doesn’t specify if that’s when she started being paid. [A 1992 Newsletter story says the agreement was for Lucy to volunteer 40 hours a week from September to mid-November, 1990, after which she would go on salary, which she would fundraise. By mid-February 1991, Lucy had done a lot of events and a lot of fundraising; but due to a financial crisis, they terminated her contract. Vol. 11, no. 20, January 1992.]

In February 1991, I moved away from Durham, stopping my involvement in The Newsletter and Our Own Place. My partner at the time had just graduated from veterinarian school at North Carolina State University. She was offered a position in a rural, equine, veterinarian practice in the mountains, which was her top choice. We lived in Marshall, North Carolina, in Madison County, 35 miles from Asheville.

Initially, I went to work for Community Connections, an Asheville newspaper for lesbians and gays. I was called “executive editor” at the time, but I did a lot of projects for them, including desktop publishing, and just plain editing. I was a jack of all trades for them for about six months [see story in The Newsletter, vol. 11, no. 5, May 1992, p. 2]. Also that year, the statewide gay pride march was held in Asheville. The Community Connections had agreed to do the pride promotional brochure, and I did that.

I got a job as publications manager for a research organization at University of North Carolina, Asheville. I eventually moved back here to Durham, doing other work in publishing. Somehow, I never dove back into community volunteering the way I had before. I did serve for a couple of years on the LGBT Task Force at Duke University. That was 2002 to 2004, I think, and it was several years after I had returned to work at Duke. The LGBT Task Force was very interesting work.

During those earlier years in Durham, it was so powerful for me being with both of those organizations for the time that I was, as the board member of Our Own Place working on fundraising and publicity; and on the committee that published The Newsletter. It was the synergy of it: organizing, making something happen in the community, and having the ability to communicate about it, all during the process, to a sizable group of women in the community. The two fed each other very well. The Newsletter enabled OOP, and many other organizations and projects, to accomplish more. And my reporting and commenting on these events and actions made The Newsletter current and vital. On a practical level, I always knew the newsletter deadlines, getting articles in, and the calendar items posted. I could tell the OOP board what was going on with The Newsletter, and what was coming. Having these different affiliations in one person worked well. And it was very satisfying to me to be able to pull those threads together.

Issues OOP Addressed

Several noteworthy issues came up at Our Own Place during the time that I was there, starting with whether to keep the space for women only. The organizing structure of Our Own Place was that decisions were made by consensus of members. Meetings were open to all women; but only members could vote and participate in consensus decision-making. We had four separate meetings about “gender inclusivity,” and the final outcome was to keep the space women only, except for children twelve and under [as reported in the October 1990 Newsletter, p. 7]. There wasn’t a lot of controversy once the decision was made. There was some dissent. However, most people, I think, were fine with it.

Also, there was a whiteness to Our Own Place that was common to a lot of organizations in this area. That was very unfortunate because the area is certainly not white. It means that when you look at the results, an organization isn’t welcoming to everyone. That was the case with Our Own Place. Mandy Carter served on the board. No other women of color did. The membership, by consensus, decided early on that a certain number of board slots would not be filled until they could be filled by women of color. And that basically never happened.

Throughout its history, at least that I know of, and it ended not long after I left, Our Own Place was operating with half of a board. No one could manage to recruit women of color for the board. That was a big issue and a big problem. There was some diversity in the membership, just very little. None of us could figure out what to do to change it.

Another thing for me as a board member and a Newsletter person was to come up with different ways of using the space, to recruit or to create groups that could make use of it. It was a simple thing to schedule something, put it in the newsletter, and see if it would fly. I repeatedly scheduled antiracism discussion groups at Our Own Place, to which only one other person besides myself ever showed up. That was just monumentally depressing. Month after month, I would schedule that antiracism discussion in the newsletter, put it in the OOP calendar, and mention it in newsletter articles, trying to interest people. It was a plea that went out, and an attempt to enroll some people in the idea that this was a worthwhile and necessary topic of discussion. It just didn’t work. I don’t know why. There was a large, educated class of diverse people here. You would expect many people would want to get together to talk about antiracism.

The lack of diverse representation wasn’t just a problem for OOP but for a lot of other organizations as well, including The Newsletter, which was almost entirely white, with zero women of color on the core publishing committee. That was also true of the organization NARAL Pro-Choice America [now known as Reproductive Freedom for All], North Carolina chapter, and the Triangle Lesbian Gay Alliance, if I’m recalling correctly. These other organizations may not have been white to the extent that Our Own Place was. Maybe they had a couple of women of color on the board.

Some organizations, the Lesbian and Gay Health Project for example, had more volunteers and board members who were women of color. That still did not reflect the local demographics. I was left with the theory that when white women, or white LGBT people, got together to set up an organization and its goals. Then, they went about recruiting people of color, and that didn’t work. It was already defined. Why would anyone think it would be a place for everyone if it was already defined by white people? That may have been what happened with Our Own Place, and with The Newsletter.

Rose Norman: SONG (Southerners on New Ground) is the only lesbian group we’ve interviewed where the founders were both white and women of color, and where they had that built into the structure of the organization.

Laurel Ferejohn: SONG is certainly a success story. And the founders included women of color. That wasn’t the case with Our Own Place. Right away, we tried to make the board half women of color. But the founding had already occurred. And the fundraising had been going on for five years, which was all white, and everyone knew that. It wasn’t foundationally diverse, as SONG was. SONG is still going strong.

Other Lesbian-Feminist Activism

I did want to touch on some of the other activism because it all seemed like part of the same thing: lesbian-feminist space, newsletter, actions. I was involved at the same time as a volunteer and activist in a few other organizations. My involvement with The Newsletter also fed into those other things.

I would participate in something, and I’d write an article for The Newsletter. Or I would know about something that was going on, and I’d make sure it got into The Newsletter calendar for the community to find out about it, in order for readers who might choose to lend their voices and presence. There was a lot of synergy there.

As I went through back issues of The Newsletter, I came across a few things I’d like to mention. June 28, 1988: “Local Gay and Lesbian Protesters Get Arrested” is an article that Elizabeth Edmiston and I wrote for The Newsletter, vol. 7, no. 21, August 1988, which includes a photo of us three who were arrested. We were protesting North Carolina’s U.S. Senator Jesse Helms, whose homophobic actions in the U.S. Senate affected AIDS policies. He was rabidly homophobic, saying things like this: “We should round them all up, and put them in concentration camps.”

The Triangle Lesbian & Gay Alliance decided to do an action to raise awareness among the general public of his ridiculous positions, and to get some mainstream publicity for these issues. I was one of those demonstrators. The demonstration was outside Helms’s office in Raleigh. We had been warned by the building manager that this is federal property, and that if we breached its wall, so to speak, we could be prosecuted under federal law. Instead of staging a sit-in inside the building, which was the original plan, we decided to sit in the street and stop traffic. The street was not federal property. The three of us who agreed to sit down in the street were supported by others protesting at the curb. We stopped traffic. When police arrived, we got arrested.

This action did get reported in the papers although not exactly in the way that we had hoped. According to the article that Elizabeth and I wrote, one television station, WRAL, showed a clip of Helms talking about quarantining people with AIDS as the TV commentator talked about our action. That was appropriate, and we got the word out that this was what we were targeting: this hideous, inhumane position Helms was taking. Other news outlets, like the Durham Morning Herald, ignored it; or they just said that gay people had a demonstration and got arrested without reporting what and why we were protesting.

For me, personally, it was an amazing experience. However, it was also a pretty harrowing one in the aftermath because I almost lost my job. I was the managing editor of a medical journal. When the editor of the journal found this notice in the Raleigh News and Observer about certain people having been arrested in this demonstration, he saw that my name was printed. He called me up on the telephone. He had no idea that I was an activist of any kind, let alone an activist around gay and lesbian issues. I explained to him my reasoning, that AIDS is a major public health crisis, and that here, a U.S. Senator, for political reasons, was basically proposing that we make it worse and not better. I said that I hoped he could understand that. He was a doctor and a decent guy. He came around, and he understood it.

But the business manager of the organization that published this medical journal decided he had it in for me. I went to a business event, a dinner and dance, and that business manager cornered me, and he tried to sexually harass me. He threatened to convince the editor and board of directors to fire me if I didn’t go along with him. I recruited a couple of women there from other medical journals to chaperone me out of the room to my hotel room, and he gave up on that. As a result, I soon left that organization. That was what we were open to when we weren’t out and couldn’t be out. Every organization where I worked after that, I made sure it was okay to be out, and I was out. I wasn’t going to let that happen to me again. That was all fallout from that one action and arrest.

October 1988, Durham Morning Herald

See “Dialogue with the Enemy: Gay and Lesbian Activists Talk to The Durham Morning Herald, The Newsletter,”vol. 8, no. 1, October 1988, pages 2-8, where The Newsletter story prints questions and answers from the meeting.

I mentioned the Durham Morning Herald as being a paper that didn’t even bother to report anything about our activism. They were notorious for their bigotry, their homophobia. (We used to call them the Durham Morning Fishwrap.) For example, the actual first march had taken place almost a decade before, yet when we had the first, annual, Gay and Lesbian Pride march here in Durham in 1986, they published editorials excoriating the community. The Ku Klux Klan in turn planned a march the following week to counter us. The Klan march was in downtown Durham. The Durham Morning Herald published an editorial saying that the Klan and gay rights activists should be made to pay for their own “parades,” that the public shouldn’t have to pay for their protection, and lumping us together. They were sorely in need of an education.

I and others wrote some letters to the editor of the Durham Morning Herald. Also, one of the things I decided to do a year or two down the road, when the newspaper got a new editor, Rick Kaspar, was to invite him to come to talk to a group of gay and lesbian activists, to sit down in a room together with us, and to hear our concerns. Surprisingly, he took me up on it. He came, and he brought his editorial page editor, Jack Adams, who had written just horrible, antigay editorials. Mandy Carter was at that meeting; and Joe Hertzenberg, a member of the Chapel Hill town council at that time; Nancy W.,from the Triangle Lesbian & Gay Alliance; Carol A., from the Durham Human Relations Commission and the 1986 Durham mayoral antirecall effort; and me. In those days, for safety reasons, The Newsletter used only first name and last initial.

It was a good discussion. We presented our concerns, and they tried to answer them. The way it ended up, as I recall, was that we came to an understanding. When members of our community wrote letters to the editor, those would get a fair shot at appearing in the paper, and not be discarded just because of the politics of the people who wrote them. We also tried to pin them down on their approach to the writing of editorials, including who vetted these, who decided it was okay, for example, to lump the Klan and gay activists together. That, of course, had not happened on the new editor’s watch. He was taken aback by that, and he seemed a little ashamed.

Things at the newspaper did seem to improve somewhat after that meeting. It could have been because he was new, taking a different tack. I’d like to think that we had something to do with it. Who knows? I found it helpful in trying to understand what this paper was all about, what were their blind spots, and what changes might be possible in the future. Now, I think the Durham Morning Herald is much friendlier and accepting today, and has been for a few years. It’s a bit more reflective of the community. But back then, at the time, it was just awful.

Our Own Place Events

Our first, real event was the grand opening, March 10, 1990. Loli Oates sang, Louise Kessel, a professional storyteller who lived in the area at the time, told stories. I can’t remember who else was there. It was held from 3 pm until 1 am, one performance after another. The Newsletter story says, “Roxanne Seagraves told erotic stories. And there were Triangle musicians, Tracy Drach, and the band Trillium, as well as Asheville’s Ellen Hines.” See Sarah Lauren Palmer, “A Very Grand OOPening!” The Newsletter, vol. 9, no. 15, May 1990, page 2.

We didn’t pay the performers a set fee, offering them a percentage of the door instead. That way, they wouldn’t go home empty handed. They probably had a tip jar, too. These performers really wanted to be there supporting this project. I believe we asked for donations of $5, or probably a sliding scale $3 to $6 or so. More than a hundred women showed up for the grand opening! We were very happy. We sold soft drinks, and we might have had beer. We made money from the tickets at the door and the sale of beverages. Some people signed up for memberships.

It was a success as a fundraiser, and it was a success in terms of good, word-of-mouth publicity. People had a really good time. The only wrinkle that night was that the police showed up. A few women took their shirts off on the porch, totally treating it as lesbian space. It turned out to be something that we should have anticipated, raising awareness about that being illegal. This was in a regular, Durham neighborhood, and the neighbors had called the police. It ended up not being too bad. The police just explained the problem, and we assured them we would take care of it.

RN: Was it mostly Triangle area performers doing these events for free?

LF: We did have Ferron come to perform for us once, and some performers from other parts of North Carolina. Mainly, during my time there, it was local talent. We all looked forward to a future in which we could pay performers, but it never became possible. For a lot of the performers, it was good just to have another place to perform, and a tip jar was fine. They were very generous and supportive of the lesbian space. We also had movie nights, raffles, and discussion groups. Those all show up in the calendars of The Newsletter pages that I gave you. Anytime there was anything happening in the space, we suggested people make a donation. Only big events had admission charges. For an organization that had no budget other than what we raised that month, the only way to do an event was to have it on a shoestring.

I raised about $1,100 a month from about October 1989, at least until Lucy started in October 1990. By the time I left in 1991, I was burned out. I loved doing it, but I was exhausted from working full time while doing this work, too. When I moved to Asheville, I just found myself in a sort of almost comatose state. I had to rest. When I started working for Community Connections, it was part-time.

By the time I took the full-time position at the University of North Carolina, Asheville, it had been about six months, and I was back up to speed. But I never got back to volunteering as much as I had. I think it was because I was burned out. I was 41 years old in 1991, still young.

I think the burnout factor was important in the fate of Our Own Place. There was a very active group of women, including those who had started it. And there were women who had run The Newsletter for so many years. Some other organizations, like TALF, had already bitten the dust by then. Triangle Gay and Lesbian Alliance and NARAL-NC and lots of other organizations had been supported by volunteers. At some point, people who had been the backbones, so to speak, for years, started opting out. It was time for a rest. Those were the people who were the most powerful agents of lesbian community development in the Triangle.

Other people had different approaches, and they may not have been committed in the same way to giving their time, giving their money, giving their commitment to an organization. If Our Own Place had come along a decade earlier, there would have been no stopping it, at least for a decade. But by the 1990s, it was very difficult to recruit people willing to sign on for that kind of committed endeavor. Many of those who would be inclined to do it had retired from such things. That’s certainly true of me now. I consider myself retired from such things. Politics aside, I’m not able or willing to put in the time and effort, the sweat and tears that it takes to pull off something like that. That was the case for many of the women who were pivotal in the 1970s and 1980s, and who were near the age I am now 65, back in the 1990s.

This interview was edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

OOP Stories in The Newsletter, 1989-92.

Other Newsletter stories, 1988.

Timeline: Our Own Place (from The Newsletter Monthly OOP Calendar, and selected issues)