KC Wildmoon:

Gail Reeder interviewed KC Wildmoon at KC’s home near Atlanta on June 11, 2025.

Family Background in Tennessee

Gail Reeder (GR): You are a cofounder of the band Moral Hazard, and you were a longtime member of the Atlanta community. Did you grow up in Atlanta?

KC Wildmoon (KCW): I grew up in East Tennessee, in an itty-bitty, tiny town called Russellville, unincorporated. [Russellville is northeast of Knoxville. Population in 2020 was 1,062.]

GR: Did it have a traffic light?

KCW: No. It just had a highway that cruised through it, and passed my dad’s service station.

GR: Did you work in your dad’s service station?

KCW: No, not really. I just kind of wouldn’t. I liked to hang out and watch. He had the greasy hands of an auto mechanic, and he worked on my grandfather’s farm. He baled the hay for my granddad. But mostly, he worked at the service station because my granddad got too old as things started changing. He sent my dad off to automatic transmission school to learn about how to do all the “mechanic” stuff. My dad ran it until he retired, in his seventies.

Running Away from Home

GR: How did you end up in Atlanta, Georgia?

KCW: I ran away from home. What actually happened was that I went to college at Tennessee Tech in Cookeville. It’s probably about three hours away from where I grew up, and it was the first time I had been away from home for any length of time. I was the proverbial fish out of water, not knowing what I was doing, what was going on, or anything. I had picked up guitar when I was a freshman in high school [in Tennessee]. I had the mumps over that Christmas vacation, and I had nothing to do. Dad was a bluegrass bass player and guitar player. I told him I wanted to learn how to play guitar. He bought me a chord book and gave me his guitar. I taught myself how to play. By the time I got to college, I was playing. I played out places while I was there.

But everything got really, really weird for me because the world was really different from how it was in my tiny little town in East Tennessee.

Biographical Note

KC Wildmoon left the lowlands of Tennessee for the bright lights of Atlanta, Georgia, after realizing music would be a much more interesting pursuit than accounting. Eventually finding a few music gigs and a lot of lesbians, she joined a production of women artists. When she met Jan Gibson, that was the beginning of the band Moral Hazard. A song celebrating the members of the band gave birth to her surname, Wildmoon.

Along the way, KC began writing, often with an irreverent flavor, music and theatre reviews for the GLBT newspaper Southern Voice. This launched a writing career, including a sixteen-year stint at CNN, and eventually a job as deputy editor for CrimeOnline.

KC, and whichever cat is running her life, hopes to leave the southland and move to the more liberal north. She’s still writing and, we hope, still making music.

It was toward the end of that first year in school. I can’t remember exactly what happened. My mother, who was kind of a tyrant, got really angry with me about something. She told me that I had to come home at the end of that school year. She said that if I still wanted to go to college, I could go to the community college in the nearby town. She emphasized that she was not going to let me live at the college.

I said, “I don’t like that idea.” What I did was play around, playing solo music around here and there a little bit. I wrote a letter to my parents, saying, “I’m not coming home. I’m going to stay here. I’ve got a job.” I had gotten a job, and I had gotten a place to live near the school. It was so exciting, and I was telling them that everything was going to be good, that I was going to be interviewed on the radio on this particular date at this particular time. Bad idea! They were waiting for me at the radio station.

GR: Oh, no!

KCW: Mostly, my dad was there along for the ride. It was my mother’s huge self that was driving this. She insisted that I was to go home with her. I insisted that I was not.

GR: How old were you then?

KCW: I had just turned eighteen. I insisted that I was not going home with them. They said, “Okay, well you need to give us your car.” My dad, being a mechanic, would buy cars and work on them to fix them up. I would drive them while this was happening. Her saying that I needed to give him my car meant the car that my dad had given me that he had been working on. I said, “Okay, that’s fine. I have to go get it.”

I had a friend pick me up and drive me to go get it, and I told them to meet me at the dormitory because I wasn’t going to have them come to where I lived. I waited and waited and waited, and they never showed up to get the car from me.

GR: Did you do the radio interview?

KCW: No, I never did the interview. While we were at the radio station, they called the police. No actually, they didn’t. It was the campus police who called them because I was no longer a student. We were in the campus police office, and they said, “Well, you’re not a student here. We [campus police] can’t do this anymore. You need to leave.”

The police came and said that my mother literally got the police chief out of bed to come and talk to me at the police station. We went to the police station, and the police chief came and talked to me. Later I found out that after I had left, he told my mom, “She’s eighteen; you can’t make her go home.” When I got the car, my parents didn’t show up. I called back to the police station, and the police told me, “No, they’re still here. They said you’re supposed to come here.” I was exasperated, and said, “Okay.”

I got my friends and took the car down there. I was walking through the door of the police station to give them the keys when my mother dragged me back into the police station, right up to a guy whose badge number I still remember, “565.” I said, “Would you please tell her that she can’t do this to me.” He said, “Calm down, young lady.” [Laughter] Well, he did tell her, and it finally ended. They took the car and left. I stayed, and everything was miserable, and I was totally a disaster.

GR: They left you there without a car?

KCW: They left me there without a car.

Moving to Atlanta and Finding Gay Community

KCW: A lot of things happened that I don’t remember very clearly. I ended up coming to Atlanta. I had met a woman who was a talent agent, hoping that she would help me get some jobs. She didn’t. I came to Atlanta without help. All by myself in Atlanta, I was an even smaller fish, and even more of a fish out of water.

I looked around me, and everyone I knew was gay. I thought, “Am I gay?

I really like this woman. I must be gay.”

That was in 1975. I ended up staying at the Salvation Army Girls Lodge on Peachtree Street in downtown Atlanta for a while until they got sick of me, and told me to leave. It was a mess, a total mess. I have very foggy memories about that time. I didn’t know what I was doing, or anything about Atlanta. Plus, I had no experience being in a big city.

Here’s a really funny thing. For probably the first six months that I was in Atlanta, in Midtown Atlanta on 6thStreet, I had the idea that cities are full of big, huge buildings. At that time, that area was not at all full of big, huge buildings. I thought that I was in a suburb for a long time. I didn’t realize it, but I was actually in downtown Atlanta. Eventually, I ended up in Austell, Georgia [a small town west of Atlanta] for a while, trying to figure out how to be, how to know. I just didn’t know.

Somewhere along the line, I met a woman who was a student teacher from Antioch College. I can’t remember how I met her. I wrote for an alternative newspaper, The Great Speckled Bird. [The Great Speckled Bird was an underground newspaper published in Atlanta, Georgia from 1968 to 1976.] I did a lot of these kinds of things. I met this woman, and I just thought she was so cool. Suddenly, I looked around me, and everyone I knew was gay. I thought, “Am I gay? I really like this woman. I must be gay.” That was the moment of my coming out. She wasn’t gay, but she was very cool and very sweet. She never treated me like anything weird. That was when I came out.

I actually began working on the committee for Gay Pride. That was mostly a party for gay boys.

I was there when we added the “L” to it, and I was there when we added the “T” to it.

That was later in 1975 or early in ’76. I fell into the gay community at that point. I spent a lot of time at the Sweet Gum Head, which was a drag bar, my favorite drag bar. I met more people. I tried to grow up, but it was a long and slow process. I pretended to be a lot more “with it” than I actually was. I was totally terrified. Totally and completely terrified.

Somewhere along the line, I actually began working on the committee for Gay Pride. That was mostly a party for gay boys. I was there when we added the “L” to it, and I was there when we added the “T” to it. The boys fought it like crazy because they did not wish to make that change. They just wanted it to be their party. It was an interesting time. I was slowly beginning to grow up, becoming a real human instead of a scared kid, which is mostly what I was for most of those early years: a terrified child, who had no idea.

Finding ALFA, “Other Harmonies,” and Jan Gibson

It was probably in the late 1970s that I found ALFA, the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance. I thought, “Okay. This is more normal people.” I found them although I was still a fish out of water, even with ALFA. I mean if you talk to some of the people who knew me back then, they thought I was insane. Which pretty much, I was. I played some music, and I met Jan Gibson and some other people, the Teeter twins, Alice and Ellen, and Leslie Williams. I started meeting and finding actual, real people. Even though I wasn’t there yet, I recognized in my heart that they were more like what I probably would be once I figured out who I was. But figuring out who I was takes a long time for this kid.

Somewhere in the late 1970s, there was an actress here, Grace MacEachron. You may know her as Grace Zabriskie. She made movies and television as Grace Zabriskie. When she was here in Atlanta, working at the Alliance Theatre and those kinds of things, she was Grace MacEachron. She actually did that HBO show about Mormons, Big Love. She played the mother of the main character in that one. She was really a fascinating woman, and I really loved her. She put together an event called “Other Harmonies.” It was a conglomeration of women who were performers of some sort: poets, mimes, musicians, dancers, and all of this. She put the entire production together, and she was the director.

I was part of that, and Jan Gibson was part of that. Jan was primarily known at that point as a poet. She also played guitar and sang some songs. But when she delivered her poetry—powerful, powerful poetry—she was alive and vibrant. She was just something else! I mean, really something else.

Beginning Moral Hazard

I already knew Jan when we started doing “Other Harmonies.” During the course of this, I played guitar for a mime. I brought up something to Jan. I said, “What if I play guitar and you sing? Then you can sing like you do your poetry.” She thought that could work. We did it, we tried it out. She was living near Oakland Drive at that point. We sat in her kitchen one night and tried this out. I played some of her songs, and we just invented some. Jan Riley [another Atlanta singer songwriter] was there, and we actually wrote “Bomb Shelter” that night, the three of us sitting there. It worked with me playing guitar and Jan doing her poetry. She was just amazing!

We thought it would work. Now we needed a band. We talked about it for a while. It was 1980, and I remember one night when Jan and I were at the Sports Page. People familiar with Atlanta in that era would remember the Sports Page, a lesbian bar on Cheshire Bridge. Jan and I were sitting at the Sports Page, and we were looking at the TV above the bar. We sat there, realizing that Ronald Reagan was going to be president, and there was nothing we could do about it. We decided at that point, yes, we’re going to do this band. Because of Ronald Reagan.

We waited at Charis until the theatre was ready for us. Then, we rushed over,

pulled all our stuff out from under the seats, set it all up, and did the show.

I don’t remember how we ended up with Jan Gibson, Jaen Black, and JB Sapp. I don’t remember how that happened. I think there were a couple of other people who came and played a little bit for us. But these two, Jaen on drums and JB on bass, stuck with us. JB had very little performance experience and was shy onstage. We used to joke and say in the early days that we were going to put a shower curtain around JB so no one could see her, and she would feel more comfortable. Jaen, too, was really new at being in a band. Jaen, as you probably know, came from Red Dyke Theatre. She had a background in theatre and performing. Somehow the four of us got together, and it worked. It worked! That’s how Moral Hazard actually came together.

Jan started putting together the show, “Flight 101.” We had been messing around with people, and we were friends with the folks at 7 Stages Theatre Atlanta, owned by Del Hamilton and Faye Allen then. They had agreed to let us do our show at midnight, at 7 Stages Theatre after a production of Mother Courage, a Bertolt Brecht play that they were doing. If you are familiar with Brecht and Mother Courage, in particular, it’s a very long, slow play. We never got started at midnight. It was often later. But we would prepare to do the show, and we would put out all the information about it happening. By this time, we had gotten Jayne Pleasants to be our stage manager.

We met at Charis Books and More, the feminist bookstore over on the corner across the street from 7 Stages Theatre at that time. That was where we would prepare to get ready to go on. We waited at Charis until the theatre was ready for us. Then, we rushed over, pulled all our stuff out from under the seats, set it all up, and did the show.

The very first night, we had no idea if anybody was going to come. We didn’t know what was going to happen with this. We were over at Charis, nervous as hell, just hanging out among the books. At one point, Jayne Pleasants said, “Hey, come over here, come over here. I’ve got to show you something.” She led us to the front door and pointed down the street. There were people lined up at the door of 7 Stages Theatre, and the line went all the way back around the corner, past Eat Your Vegetables, the restaurant, and out of sight. They were lined up, waiting to get in to see us.

We thought, “Oh, my God! This is going to work!” We did that performance for a couple of weekends, and it was apparently wildly successful. People really, really enjoyed it. We did all kinds of crazy, crazy things. It was largely spoken word, Jan’s spoken word, some of her poetry strung together through the show. Jan Gibson is brilliant! I cannot say it enough about her. She’s just so good.

GR: Jan is amazing at so many things.

KCW: Yes, she put this thing together, and somehow, we strung the music with it. We did songs, and some would be songs that she had already written with some new songs that we wrote in the course of rehearsing. We put the whole show together and performed it. We had two other women who were theatre people, Janet Metzger and Jo Leavitt. We called them the “snake” dancers because of the way they moved in their dances with a snake-like weaving thing, in and out of the whole production. It was really fascinating. They kind of augmented the performances that way. Janet and Jo performed with us in those first two shows. We had other snake dancers later on, but they were the first two.

Moral Hazard Shows and Festival Gigs

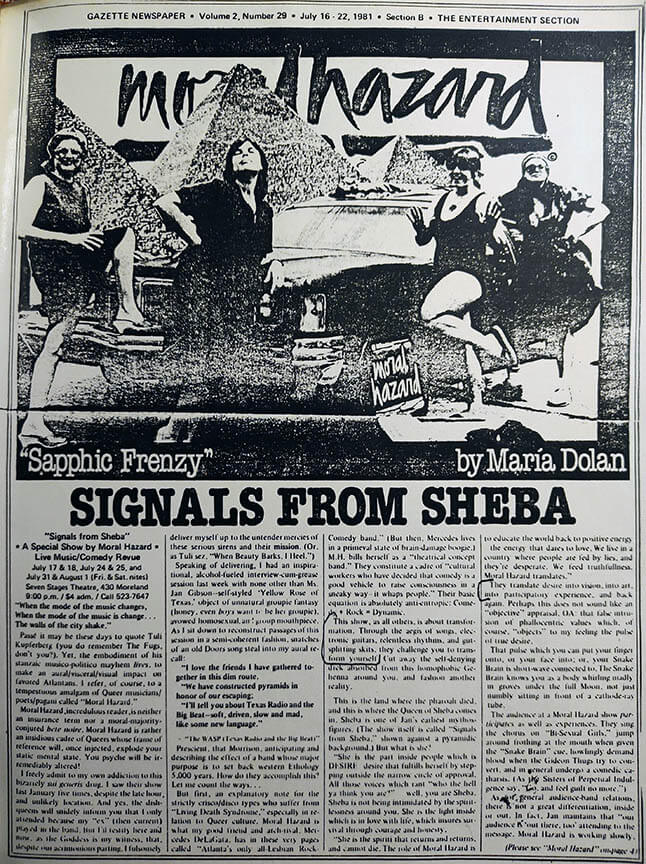

That first show was so successful that Del and Faye, the owners, wanted us to do a second one. Jan started working on “Signals from Sheba,” which we eventually did at 7 Stages Theatre. I think “Signals from Sheba” was at a regular time, not at midnight. Del and Faye came to us and said, “Hey! We’re going to do a benefit for the theatre. It will be at the Little Five Points Pub down the street. Would y’all be interested in just playing some music for it, just music?” We said that yes, we can do that. We could play some music. That was the first time we had ever done just straight music, and that’s when we found out that people liked to dance to our stuff. It was wonderful.

I don’t think we ever took the show, “Flight 101” on the road, but we did take “Signals from Sheba” show on the road. We performed it in Athens, Georgia; in Tallahassee, Florida; and in Knoxville, Tennessee. We went all around with with that performance. It was really quite fun.

In the meantime, we did music performances at the First Existentialist Congregation of Atlanta, which we called “the Vitamin E Church,” and places like that. We just played music for people to dance. That’s when we started to do a few cover songs that people would recognize, some rockabilly kinds of rock and roll. People danced, and they loved it. It went on and on and on like that. It was just amazing, just amazing. We had a thing. We had a good thing.

GR:Why do you call it Moral Hazard?

KCW: We called ourselves Moral Hazard from the very beginning. Jan came up with it. She found it in the dictionary. “Moral hazard” is some kind of insurance term that means what you would think it would: a moral hazard. She thought it was a good name for us. We had been joking around, trying to figure out what we should call ourselves. At first, I suggested that we call us “KC and the J’s” since it was me and Jan, Jaen, and JB. But I was never serious about that. When Jan came up with Moral Hazard, we were like, “Yes, that’s us! We’re a moral hazard.”

We did other shows from there. We stretched out and did some performances at the Nexus Theatre. We performed at 7 Stages Theatre when they moved down the street, and continued to do the musical things. Eventually, we all had different ideas of who we were individually, and the band just fell apart. But we had a long run, and it was good.

We started in in 1980, and our last show was in 1993, I think. We performed at Gay Pride a couple of times, too. There’s probably stuff I don’t remember.

After that came Tammy Whynot. Tammy Whynot’s backup band became the Even Strangers.

GR: Tell me about the bands Anima Rising and Tammy Whynot.

KCW: I was with another band that I played with, Anima Rising, in the late 1970s. Anima Rising was with Beth York, and Jan Riley came in later. Jan Smith and Phyllis Free were in it with us, too. [Anima Rising’s last performance was at the Pagoda in St. Augustine, Florida, on September 15, 1979.] That band were very pop-music oriented. I thought of it because Anima Rising played at pride festivities before Moral Hazard did.

During the course of all this, we started doing Tammy Whynot with you [with Gail Reeder]. I had always wanted us to do a country thing. I thought of calling it Merle Hazard and the Even Strangers, based on Merle Haggard, whose band was The Strangers. We would be Merle Hazard and the Even Strangers. There were the “Landofill Sisters.” JB was Chlorine Landofill and Jaen was Tundra Landofill.

After that came Tammy Whynot. Tammy Whynot’s backup band became the Even Strangers. JB talking about their names for that band reminded me that I had a name in that band, too. I was part of an improv theatre group around then, ACME Theatre. We did a lot of strange things, and one of them was a country music “super group,” a la Alabama, that we called Lithonia. We all had different characters to play in Lithonia, and mine was Kansas City Wildmoonpie, a total take on my actual name. So that was my name in the Even Strangers, along with Tundra and Chlorine.

I just found out there actually is a person who started performing in the late 2000s as Merle Hazard. We never used that name. When you started doing Tammy Whynot, we thought, “Hey, we could just back up to Tammy Whynot.”

GR: I couldn’t remember how you became my backup band.

KCW: I don’t remember how it happened either. I mean, somebody asked somebody, and it happened.

GR: We were doing the Amazon Broadcasting project at this time, with the Sisters of No Mercy. The Tammy Whynot show was going to be part of those. And of course, I needed a band.

[The Amazon Broadcasting System was a film created by an all-women comedy group called Sisters of No Mercy. Gail Reeder and Maria Helena Dolan were their two lesbian members. Gail created Tammy Whynot as a performance for the Amazon Broadcasting System film. Moral Hazard played backup for Tammy Whynot’s performance of Gail’s original song “Mama’s Gone to Heaven to Sleep with Jesus.” The song was radical and controversial in the way that Moral Hazard was radical and controversial. Gail sent the 16 mm film to the San Francisco Gay Film Festival that year.]

GR: You went to the San Francisco Gay Film Festival.

KCW: We did?

GR: Yes! We got a nice letter from them saying our sound was very good!

KCW: Excellent. That’s cool. I love that. Yes, Moral Hazard played at the Southern Women’s Music Festival, and Rhythm Fest. We also applied to play at The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, but they didn’t like the idea of rock and roll.

GR: How silly!

KCW: I know. It was totally ridiculous. I remember when I went to Michigan, and I was at a workshop that Alix Dobkin was doing. I don’t remember what the workshop was actually about, but there was a small group of women in there who were absolutely adamant that guitars were phallic symbols and should not ever be used in anything.

GR: Are violins and flutes phallic symbols, too? Because men made them all, and they all look like phallic symbols.

KCW: Yes, I guess so. But anyway, Michigan didn’t know what to do with us. They could not comprehend what we were doing. But Robin Tyler could. [Robin Tyler produced the Southern Women’s Music and Comedy Festival in Georgia from 1984 to 1992.]

GR: Yes, Robin Tyler had me do my act, Tammy Whynot, on the stage the first night, singing “Tired of Fuckers Fucking Over Me,” something Robin and I performed together.

KCW: That’s a great song! Yes, Michelle Crone, for Rhythm Fest, also didn’t have a problem with rock and roll. We did those festivals, and for a while, we performed at the old Masonic Temple in Grant Park. The Masons were long gone. We were upstairs in the building on Cherokee Drive.

All kinds of people, famous people, would come to see us and hang out.

Alix Dobkin herself came to see us over at the old Masonic Temple when we did a show there.

GR: Yes, that’s where the Sisters of No Mercy had the opening for the Amazon Broadcasting. I don’t know if you were there or not.

KCW: I don’t know, either. We also used that as our rehearsal space for a long time. We did a lot of performances there. We found some bizarro things, like a box full of left-hand gloves that were left by the Masons. I don’t know what those were about.

All kinds of cool people, even famous people like the B-52s, used to come see us. Like Cindy Wilson, the vocalist, keyboard, synth bass player from the B-52s. And Kate Pierson, the vocalist and percussion player from the B-52. They didn’t have their bouffant hairdos when they came, and no one would ever have recognized them. Wendy O. Williams came to see us, and she thought we were absolutely fabulous. She was a punk goddess for a long time [Wendy O. Williams, b. 1949 and d. 1998, was in the punk rock band, the Plasmatics].

My favorite guitar player in the world, Ellen miraculously, came to see us once. Just imagine, Ellen McIlwaine! It made me so nervous when I heard she was coming. She was friends with Jan. I remember that night because that was the night the reverb on my amplifier started to act up. I was worried that I wasn’t going to get the sound that I wanted out of it, and just when Ellen McIlwaine was going to be there. It was terrible. Then, just before the show started, my amp miraculously started working. Phew.

Ellen McIlwaine moved to Canada and died there in 2021. Other famous people came and see us and hang out with us. Alix Dobkin herself came to see us over at the Masonic Temple when we did a show there one night. [Alix Dobkin was a famous lesbian folk musician who published the first lesbian music album, Lavender Jane Loves Women, in 1973.] I don’t know what Alix thought of us. I know that she was not a rock and roller, but she did come to hear us. It was most interesting.

Sometime in the 1990s, Jan and I got together at some ALFA reunion, and that was fun. It was just Jan and me. We played acoustic guitars, doing some Moral Hazard stuff. Every now and then, we’d talk and reminisce about the good old days. I think I’m too old to do rock and roll any more. I sold my guitars except for one.

GR: Moral Hazard had the basics: lead guitar, bass guitar, drums, and a lead singer.

KCW: Occasionally, on a couple of songs, Jan Gibson played a rhythm guitar. But mostly she sang the lead.

The other Jan, Jan Riley, was not a part of Moral Hazard. She just was in the kitchen the night that we first tried to play some stuff, the night we first started messing around. Jan Riley did participate in the writing of the song, “Bomb Shelter.” She has a writing credit on “Bomb Shelter” because she was there.

I got the idea for the music for that song, “Bomb Shelter.” There was a band called New Clear Days. If you say it fast, you know what you get. It sounds like “nuclear” days. I was kind of into some punk music at that time. We called ourselves “no-wave music.” There was punk and there was new wave. We decided that we were no wave. We called our performances “no-wave musical comedies.”

GR: Was it always the basic four of you in Moral Hazard, or did you add other people?

KCW: No, we didn’t, other than the dancers, the snake dancers. Technically, Louise and Barbara were also snake dancers because we just kept using that phrase although they were real dancers. There were never any other members of the band. It was the four of us plus whatever snake dancers we had at that point. There was another woman who was briefly a dancer, whose name I can’t remember. She was only in one show. Her name was HP or something. I think there was one show where Jaen couldn’t be there, and somebody else filled in as a drummer. [A drummer named Joan played for their final show, Gaga.]

GR: Moral Hazard performed at the first Southern Women’s Music and Comedy Festival in 1984. How did you feel about that festival?

KCW: I found it to be a lot of fun, really fun. They weren’t used to rock and roll music. We walked in, we set up, and we’re did our sound check. One of the first things I do in a sound check is to get my feedback levels. You know, I use feedback on the guitar. The sound technician shut down the whole sound system because she thought something crazy was happening. She said, “What the hell is that?” I said, “Um, feedback. You’ve never heard of that before?” I couldn’t believe it.

I remember the night that we played at Southern. Cris Williamson was playing immediately before us. They scheduled us to play late, very late. Cris Williamson played right before us, and we thanked her for opening for us as a joke. What fun. I think we played a second time, another year. But that first one was the one that I remember the most.

I also remember Janet Snyder telling us later that when she had seen us going on the stage, she thought, “Oh, look, a bunch of hayseeds coming up here.” I mean, we were wearing our jeans and all. She was surprised that we turned out to be kick-ass rock and roll players. Janet Snyder actually ended up recording our first demo record, which was a different thing. She wasn’t used to rock and roll.

GR: I was a disability coordinator for the first Southern Women’s Music and Comedy Festival. At the little guardhouse out front, two Southern women were playing bluegrass country music on the porch. I was just so pleased, thinking, “How perfect is this?” One of the women from California said, “Are we going to have to listen to this shit all day?”

KCW: You’re in the South, child.

GR: That’s right! They came and asked me, “Do you think that the women would prefer herb butter chicken or teriyaki chicken?” I said, “This is the South, honey. I think they want barbequed chicken.”

KCW: Yes, that’s pretty funny. But it was great to meet people like Kate Millett and Rita Mae Brown and those kinds of people there. I liked Cris Williamson and Meg Christian, too.

ALFA and the Atlanta Feminist Women’s Chorus

GR: Did you think of yourself as an activist? A feminist, a lesbian, a feminist activist, or an artist? Or as all of the above?

KCW: I was pretty political from the start, once I figured it out. As soon as I came out, I started moving into that realm of things. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I was a stupid, dumb kid for most of it. But political was the direction that I going.

Definitely, ALFA certainly did help. I took part in of a lot of ALFA projects. I helped coordinate ALFA’s tenth anniversary in the 1980s when we introduced the chorus. [ALFA was founded in 1972, and the tenth anniversary was in 1982.] That was the first performance of the Feminist Women’s Chorus at ALFA’s tenth anniversary party.

Moral Hazard played for that anniversary party. ALFA also had the first performance of the chorus there, and it was so much fun. I remember how we brought a huge bouquet of flowers to Linda Vaughn, chorus director, because it was their first performance. (See Charlene Ball, “Atlanta Feminist Women’s Chorus, Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017): 61-68).

At the time, we were just too outrageous. It was just too outrageous to have an all-lesbian band.

GR: Moral Hazard never really went mainstream.

KCW: Interestingly, somewhere in the course of all that, a small, independent record label wanted to sign us. They had a caveat though. They wanted us to tone it down. We said, “No,” and that was that. They didn’t want “us.”

Lyrically, the most outrageous, radical thing we did was in the spoken word part. Our song lyrics are pretty much milquetoast, other than “Bisexual Girl.” But for the most part, the lyrics themselves are not radical. I mean, they’re certainly not boring or anything like that. We were ahead of our time. I think that if we had we come on the scene even five years later, maybe we could have gone a little further with that. But at the time, we were just too outrageous. It was just too outrageous to have an all-lesbian band.

GR: Well, in the 1980s to the ‘90s, lesbians weren’t really in the forefront of music.

KCW: They started to have some. Melissa Etheridge, KD Lang, and those people starting to filter into fame. But for the most part, no. It wasn’t happening. It’s okay. We had our place, and we did it well.

GR: I wrote for Southern Voice and Pulse Magazine, which came out after The Great Speckled Bird quit publishing. Didn’t you as well?

KCW: I wrote music reviews for The Great Speckled Bird. I think I reviewed Cris Williamson’s first album, and Patti Smith’s Horses album. Because man, when I heard that, that was a huge musical influence. I thought, “Wow!” A lot of my music after that, and what I brought to Moral Hazard, was influenced by Patti Smith. I loved her and I still do. I still think she’s fabulous. She’s one of my favorite performers. There was a time, a few years ago, when she did a spoken word tour that came to the Variety Playhouse. I was going to go, and I was so excited. Then I got sick. What a disappointment! I gave my tickets to a friend of mine who was so excited to get to go. But I didn’t get to see her with her long gray hair. A big part of my music was Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye, who was her guitar player.

I have my dad’s double bass. My dad was a bass player. He played in a bluegrass band. I sold his electric bass. Double bass is what he played most of the time. He was a mechanic who played music and drove a school bus.

GR: You’re a Southern woman, born and bred in such a small town where the gay revolution never came.

KCW: Exactly. I think I have one cousin who is gay, but he won’t ever say it. I have another cousin who knows that I’m a lesbian. I had a piece of property in Tennessee until earlier this year, and I sold it. I had a log cabin that’s 240 years old up there. I was going to restore it to live in it. But after the elections in November [2024], I said, “There’s no fucking way I’m going to live in Tennessee.”

GR: You gave me a much broader picture of Moral Hazard, and how Jan Gibson was a poet who ended up performing and singing with you.

KCW: Jan was the impetus. She wrote a poem called, “Onward, O Greasy Americans,” which I loved. Her performance of that poem was something to behold. That was that first benefit at 7 Stages Theatre, people dancing to our music, saying, “Oh, man, people like to dance to Moral Hazard!” It was the beat.

We did this version of Bobby Gentry’s hit song, “Ode to Billy Joe.” I based the arrangement of it on the song that Ellen McIlwaine, my favorite guitarist, did. It’s slightly different from Bobby Gentry’s version, and of course, we Moral Hazard-ified it.

I got to meet Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash one time. There used to be an all-night restaurant called Gregory’s in downtown Atlanta on West Peach Tree Street. This was back in those days when I stayed up all night long. I would frequently go down there in the middle of the night to have eggs benedict or whatever. One night, I was sitting there with a bunch of friends around a table, and who walks in but Johnny and June, along with their whole entourage. They sat down at the table right next to us. I think they had performed at the Fox Theatre, and came to eat afterwards. It was pretty fascinating.

How Moral Hazard Ended

GR: The band was your life for ten or fifteen years.

KCW: Yes, it was huge. Our rehearsal space was at JB’s house in Lake Claire. JB worked for IBM then. That comes up in our lyrics on the song, “Lavender Jane Loves Money.” We rehearsed at JB’s house. Then she moved. I don’t remember where it was, but it was some bizarre place in the middle of nowhere where she bought a house. We moved there and rehearsed in her garage. We were literally a garage band, ha.

From there, we moved to the Masonic Temple space. There was sort of the dissolution of the band as it was going on in there. Janet and Jo had gone, and Barbara C. had become part of it as a “snake” dancer. I won’t say any more about that. Louise and Barbara were both primarily dancers, real dancers, unlike Janet and Jo, who were from the theatre. Things just got really weird during that time. The performances that we did were heavily influenced by the dancer, Barbara, actually.

We had some okay music that came out of that, but it wasn’t as good as the early stuff. From there, that’s kind of how it split apart. Very sad. But again, we had a long life, and it was a good one. We had something really special.

Oh, man, and it was really, really fun. I don’t listen to the music any more. I can’t imagine being that spirited. I’m way too slow and old. This is my speed now, my little, old, nice acoustic guitar. I might learn the banjo.

See also:

Beth York, “Consciousness Raising with Anima Rising,” Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017); 15-25.

Moral Hazard, Step Over This Line, CD, ten songs, 41 minutes, available on iTunes and Spotify.

Rose Norman, “Moral Hazard: The South’s First Out Lesbian Band”Rose Norman, “Moral Hazard: The South’s First Out Lesbian Band” ADD LINK TO FEATURE STORY

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee and again edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.