JB (Judy) Sapp: An Engineering Rock Star

Interview by Rose Norman in Crescent Beach, Florida, on November 29, 2024.

JB Sapp (JBS): I grew up in Baldwin, Florida. It’s ten miles west of Jacksonville, a very small town. There were fifty-two people in my graduating class. I tried to get out of Baldwin as soon as I could. I graduated from high school in 1970. That fall, I went to Florida State University. In my junior year there, I got in an exchange program that took us to the University of London, England. After I did that, I came back home and realized that I really wanted to party. I transferred to the University of Florida in Gainesville, where I graduated. in 1974. I got a job in broadcasting in Atlanta, Georgia.

Rose Norman (RN): Was your degree in broadcasting?

JBS: Yes, I got a degree in journalism, specializing in broadcasting. I got a job with the CBS television station up there as their first female engineer. That was quite the story. They wanted a female “experiment” to see if a woman could handle one of those satellite trucks. It was one of these huge, TV news trucks that had a satellite dish on top of it. The satellite dish was about the size of a king-size bed. Whenever the videographer, a reporter, and I would go out to cover these news stories, when we wanted to go live, I would have to climb on top of the TV truck, lift that satellite dish up while I was talking to somebody on a communication device back at the TV station. I’d be aiming the dish, literally, at a satellite, to be able to beam the picture back down to people’s televisions. I always tell people, “That and playing bass were the two reasons I look like a question mark at seventy.” But I did it.

I always played music. I started playing music in the fifth grade. I was probably about eight or ten when I found my first guitar in the basement of one of my relatives. It wasn’t being used, and it only had five strings on it. I knew that I couldn’t get another string, and I did my own tuning on that guitar, learning how to play guitar with only five strings. I played other instruments in the school band from fifth grade on, both in concert band and marching band. I played cornet, tenor sax, and oboe, and I just loved it. I knew that I also liked playing with audio equipment.

RN: When you were in broadcasting during university, were you interested in the technical side of it rather than the “getting in front of the camera” side?

Biographical Note

Judy “JB” Sapp grew up in Baldwin, Florida, a little town near Jacksonville, Florida. After earning a broadcasting degree at the University of Florida in 1974, she worked as a sound engineer for the CBS television affiliate in Atlanta, Georgia. They sent her back to engineering school to get her first-class FCC (Federal Communications Commission) license. In Atlanta in 1980, she became the bass player for the avant garde band Moral Hazard.

Also in 1980, when cable deregulated, JB began a freelance career that soon moved into producing a wide range of sporting events like the Super Bowl and the World Series. She worked as a contractor doing audio engineering for IBM for about fifteen years. Around 2006, she went full-time as a producer with another big company, from which she retired in 2016.

JBS: Oh, I didn’t even want to be in front of the camera. I wanted to be behind it, In fact, I worked at the campus radio station, WUFT, and at the University of Florida Television. WUFT was the Gainesville radio station. In my senior year, I got a fulltime job at the hip radio, the groovy FM station, WGVL, and everyone listened to it. I was one of the late-night DJs there. Then, I got a job as a news reporter for WGGG, the AM station. All of this was while I was still in university. I didn’t want to go home for any holidays or summer vacation, and I liked having a job to be able to stay in Gainesville.

A Cracker is somebody that lived on the land, for the land,

and just always embraced the outdoors.

I knew more about picking cotton and peanuts than anything else.

A Very Well-Educated Southern Cracker

RN: Do you identify as Southern? What does it mean to you to be Southern?

JBS: Oh, yes, very much. My family’s been in Florida for so long that we don’t even know where we originated. We’re all Crackers, and I’m proud of that. I grew up in the country riding horses. My grandparents had their own vegetable farms. I am very, very Southern. With this accent? I couldn’t identify with anything else.

RN: Southern is a positive thing for you.

JBS: Absolutely. I am very proud of my heritage. And to be a Cracker. I mean, to be one of the original Florida people.

RN: Define that for those who don’t understand what a Florida Cracker is.

JBS: A Cracker is somebody that lived on the land, for the land, and just always embraced the outdoors. I knew more about picking cotton and peanuts than anything else because I’d have to do that during the summers when I was growing up. I love the fact that I know how to catch a fish. I love Southern cooking, collard greens, and boiled peanuts.

RN: Do you think of yourself as an activist, a feminist, a lesbian feminist, an artist—any of the above, all of the above?

JBS: Definitely, an artist. That is the thing that I identify with the most. The others, I’m not sure. I’m not a radical feminist, but I certainly embrace it. I’ve never been anything else but a feminist, and I guess that it’s sort of like when you don’t know anything else, you don’t think about that being your essence. Because it’s just always, always been me. I’ve never known any other way of being.

RN: How did feminism come to you as a concept, a political concept?

JBS: I read everything I could get my hands on. I’m a voracious reader. I love fiction, I love classical novels, and I love learning. That’s been my driving force my whole life. I just love learning anything new, and something that I might not have been taught in high school or in elementary school.

The high school I went to was very backward. In fact, it was in Duval County, Florida, and they weren’t even accredited. When I graduated from high school, I basically had to get my GED [General Educational Development, a test for high school equivalency] to be able to go to college because they didn’t recognize that Baldwin High School could have somebody going to college. I had to take all these extra tests and everything to get into the university. With my high scores on those, I got to start university with something like twelve hours already accredited to me.

In other words, I “clepped” out, or whatever the word was. My first day of college, I already had like a semester’s worth of credits. [CLEP, College-Level Examination Program, is a set of exams administered by the College Board. Passing scores earn college or university credit hours.]

RN: Were there people in your youth, who were important to your ways of thinking about the politics of women’s liberation? This was the big period of women’s liberation.

JBS: No, I really can’t think of any. Again, it was just my own quest for more knowledge and education because I was not surrounded with people like that. They were certainly not in my high school or in the town where I grew up. My mother was college-educated, and she was very smart. She and my father were more together. I tell people that I was basically raised by a Black woman. I was five years old before I found out that my mother wasn’t Black because I was raised by a maid. You know, we always had a maid and a cook who took care of me, and that was it. I did have good grandparents that were always nearby.

RN: Did you have siblings?

JBS: I had one older brother, eight years older.

RN: Tell that story about the family business.

What would piss him off the most? I’ll go into broadcasting!

JBS: It’s funny. I think it was back in 1965 or 1970, my father started a construction company that grew into a railroad construction company. When my brother went to college, he just assumed he was going into the business; and my father assumed he was, too. He was going to be taking over the construction business. I thought, well, that looks great. You’re guaranteed a job when you get out of college. I’m going to sign up for that. I was in building construction classes, planning on doing whatever so I could get a builder-contractor license, that type of thing.

When I was a junior in college, my father, who didn’t communicate with me very well, said to me, “You know, we really can’t have a woman in the business. I just think you’d better plan on something else.” I knew that I’d always liked music and recording. I thought, “What would piss him off the most? I’ll go into broadcasting!” And that’s what I did. I started studying broadcasting, and I was like, okay, I like television and music, and that’s what I’m going to do. It was a sort of F-you.

RN: And your brother?

JBS: He was already working in the business. It was all destined for him. Boy, I tell you, I couldn’t be happier because I’ve had a much better life than if I had tried to work in the construction industry.

RN: Yes, you would have been constantly up against that kind of prejudice.

F’ You, I’m Going Into Television!

JBS: Yes. And wow, the travel I’ve done, the jobs I’ve had. I’ve been so blessed. But I worked hard. My father did not get me the jobs with CBS or all the networks where I worked, or any of the traveling I’ve done. None of my family had anything to do with it. I did it all on my own.

When I went to Atlanta, Georgia in 1974, my first job was with WAGA, the CBS affiliate there. That’s where I got into running the satellite truck. I was the first female engineer there. CBS sent me back to engineering school to get a first-class FCC license. I also have a university degree in electronics engineering along with the broadcasting. I got CBS to pay for it, and I worked there from 1974 to 1980, when cable got deregulated. That was when ESPN, HBO, all the networks started having their own sports programs. The fact that I also knew how to operate a satellite truck was very helpful. I decided to go freelance because I’d started playing in a rock band. I couldn’t adjust my schedule at CBS to be able to do that. You know, I’d much rather go make $50 playing rock and roll music in Atlanta with women.

I quit CBS, and hoped that I would be able to get into freelance work to support myself. In 1980, I unpacked the first ESPN remote satellite truck, where we would go out and televise football games, tennis matches, and basketball games. We would set up all the cameras. We were like a roving bunch of gypsies that would just go meet TV trucks in different places.

Freelancing in the TV Trucks

Then I met Ted Turner and some other people there at Turner Broadcasting. They started hiring me freelance to come on their TV trucks to run the audio for sporting events. It would be my job as part of the audio team to go out and set it all up.

I’ve been head audio for the Super Bowl.

I’ve been head audio for the World Series many times.

I’ve done the U.S. Open.

For example, let’s just take a Braves baseball game, for example. We would mic up the whole field, run cables, and put the microphones in specific places so that we could catch the natural sound of the balls being hit. But again, it was television, and we could have microphones on the cameras also. I would be the one in the TV truck who had set up the headsets for the announcers, for whoever was the famous announcer at the time.

RN: Like Howard Cosell?

JBS: Yes, absolutely. I would tell different people, “I’ve had my hand up your shirt” for putting a microphone on them. And then, I’d be down in the TV truck mixing the whole thing. I sat in front of a mixing board with sixty-four channels, and have my announcers on one side with all the headsets. I also had the stick mics where they do the interviews down on the field, and I was the one mixing all that in the TV truck, playing the music, and playing the video tape with the audio. That was very intense because that never stopped. I mean, I might get a two-minute commercial break, but I’d have to sit there for the whole thing. I’d always tell my friends, “When you’re watching a television sports broadcast, looking at the announcer holding that microphone up in front of his mouth, and you’re having to do lip-reading, then somebody’s in big trouble, and it’s probably me.” It’s like, “Here, read my lips!” with the mouth moving, and you’re not hearing anything. I would be in deep trouble.

I did that for about twenty years. I’ve been head audio for the Super Bowl. I’ve been head audio for the World Series many times. I’ve done audio for the U.S. Open. I got into golf. I’ve done the audio for CBS for The Masters television broadcasts. I’ve met many, many famous people. And with HBO, I actually did some boxing broadcasts. I did about two of those, and I said, “I’m not doing that anymore.” That was pretty rough. I did sports for about twenty years as an audio engineer. I also operated cameras if I had to.

At the end of these broadcasts, whether it be football, basketball, or baseball, we technicians would have to wrap up all the cables. If it had been raining, it was muddy. The cables were heavy. All of the men hated me because I couldn’t lift as much as they did. They resented the fact that, as they always used to tell me, “You’re taking a man’s job. Here’s one of our buddies that could be doing what you’re doing, and we don’t like it.” I had to deal with that.

Because I was a freelancer, I just made myself some business cards that said, “Producer/Director.”

I started going around and introducing myself as a producer/director.

I had never been in the front of the truck before. And by god, I got work!

I noticed the guys that were doing the directing up in the front of the truck. That is a very hard job because you’re calling all the cameras, you’re setting up the shots, you’ve got to put it all together, and make it look like you want it to look. I thought, “The only difference between me and them is they have a crease in their jeans. I’ll just start ironing my jeans, and I’ll get to the front of the truck.” Because I was a freelancer, not working for any particular company, I just made myself some business cards that said, “Producer/Director.” I started going around and introducing myself as a producer/director. I had never been in the front of the truck before. And by god, I got work!

That changed my life. I didn’t have to strike the equipment any more. I was like, “You boys, you go! You go ahead, and go do that.” A lot of the big companies in Atlanta, like IBM, Home Depot, Georgia Pacific, and Georgia Power all had their own, in-house television production studios. I started working that circuit. They had beautiful studios where they would make training videos. IBM was the best. I started working for corporate television, which kept me out of the stadiums. I still traveled a lot; they sent me to a lot of different places.

Then I got lucky. One of my lucky breaks was, I think, in the beginning of the 1990s. All these corporations started cutting back their television production because they just couldn’t afford to keep people on staff. Since I’d been out in the freelance world doing all these things, I knew all of the freelance engineers, camera men, television operators, and audio engineers. I was buddies with all of them. IBM hired me under contract to staff their studios when they needed it.

Executive Producer for IBM and Stupid Humans

I was an executive producer for IBM for about fifteen years, and it was a marvelous job. Again, I wasn’t an IBM employee, but I had the executive producer card. They started sending me around to all their education and training seminars where we would do what they called “the Hundred Percent Clubs,” for the people who had made the highest revenue. They sent them on a four-day vacation to places like Hawaii, or San Francisco, or down to Miami. There would be a rotating roll of about a hundred to two hundred IBM-ers, who would come in for four days, and they would be taken to all these beautiful banquets and beautiful live events where they would have all these stars come in and play for them. They would be taken out on sailboats, deep sea fishing, horseback riding, or out to play golf.

I followed them around in my shorts with a camera operator and an audio engineer to put together what I called my “Stupid Human” videos. We would take a song like, “You make me want to shout, da da da da,” and we followed them around, We then put together a two-minute video to show at their final meeting four days later. We had to stay up all night editing that, so that at the end of their conference, they’d see themselves up on the big screen doing stupid things, stupid human tricks, as I called them. I did that for, gosh, about fifteen years. That and keeping the company’s studios staffed.

Another great story was when I and some of the technicians developed a process of instantaneous capture. We would go and capture the audience of all the subject matter experts at these educational conferences all over Europe, Hawaii, everywhere. We’d capture all the assets of digitized audio, and we developed the technology for that. We could process it, and put it up within fifteen minutes of having just recorded it. We’d put it up on a satellite so that people who didn’t get to watch that class live had it within fifteen minutes. We were able to download the whole subject matter of the expert, all of it. That was a lot of fun, too. I traveled the world with IBM.

RN: How many years were you with IBM?

JBS: About fifteen years,1990 through 2005. And then, that bubble kind of burst because everybody started doing it. They took our technology, and started doing it a lot cheaper and with lower quality. In other words, we were doing really high-end audio, and people found out that they could just record it on their cameras. And that’s kind of what happened. We had to give up all the good equipment.

Disney sent me through the Disney Legends School where I got all their traditions.

They spent six months just training me about Disney.

Disney and the American Idol

I was still in Atlanta, and Disney contacted me. They wanted to start a thing called “The American Idol Experience” at Hollywood Studios, which is where people would come. It was an exact replica of the show that was on television, where people would come and audition. We spent a year and a half building and designing the studio for it, and all the parts of it, and they hired me to come down because I’d done some freelance work for them as a television director, and they kind of knew what I knew. They hired me full-time, and that was at a time, I think that was 2006, maybe 2007, where it was hard to get a full-time job with Disney with all the benefits and the insurance. As a freelancer for thirty years, I had to take care of all my own healthcare and my retirement. I didn’t have a boss. I was my own boss.

Disney sent me through the Disney Legends School where I got all their traditions. They spent six months just training me about Disney, which was a fascinating experience. I remember when they offered me the full-time job, I said, “Okay, let me get this straight. You’re saying full-time, this is not just a part-time seasonal. You’re offering me a full-time job?” This was when I wasn’t exactly a youngster. And they did. I got to retire from Disney with a pension and everything. I helped design the American Idol Theatre, and the whole show, which we had to teach to the other stage managers that had never directed or called a live show before in their lives.

RN: That’s a version of activism, to get ahead in a nontraditional career for women.

JBS: Absolutely, because I would be the only woman on a forty-man sports crew, and they were not kind to me. When I think about now, the things that people get sued for, like sexual harassment—it was just awful. I had to develop such a thick skin with it. It would even be on the headsets, like the whole TV crew, all the cameramen, everybody in the truck, the Chyron people [electronically generated captions], people that did the typing. Everybody was on a headset, and listening to the things that were being said. To this day, it just takes my breath away that people, men, could even do that. I asked, “Do you talk to your wife like this? Do you want somebody talking to your daughter like you’re talking about me?” Then again, I had some folks who were just my heroes, that I’m still friends with today. There were a couple of good ones that stood up for me. But boy, there weren’t many. I don’t know why. I guess I was just a masochist to go into the most difficult thing like that. Then when I got into corporate, there still was a little of that. But it was so much better than those truck drivers that were driving these huge semis, you know, the TV trucks for setting up stuff and everything. It was brutal. It really was. I don’t know how I did it. Rock and roll really got me into it. I should focus more on that with you.

Revisiting JS Productions

RN: We’re just going to go back a moment to when you were doing JS Productions, freelancing, and spending—say all that again.

JBS: It was six to eight weeks in Maui at the Ka’anapali Resort because that’s where all the IBM-ers would come. I’d have to go boating with them, horseback riding, out on the golf course, and then go to these fantastic concerts. I remember Hall and Oats was one of our big performers. Their band and our production stage crew would have softball games on the weekends. We were there for four to eight weeks, staying in the same beautiful hotel room. One time, I was at the Fontainebleau Hotel down in Miami Beach for four weeks, also the Doral. I would be over in Barcelona, Spain; Lisbon, Portugal; France, and the south of France, just incredible travels. And San Francisco. And that was just corporate. That doesn’t even mention the sporting venues that I got to see.

I may not have been able to lift the most cable, but I was one of the best mixers out there.

One of my favorite stories when I was doing sports was this. They would book me for all kinds of bizarre events, a year in advance, because as I said, I’ve done the Super Bowl, the World Series, and golf tournaments all over the place. One time, I got a job to do a ski tournament. This was in January or February. I thought, okay, that won’t be so bad. I’ll probably be down in Miami. It will be nice weather, so I’ll go ahead and accept this. Well, it was for ABC, and I accepted the job to do the audio for the ski tournament. About a month before the ski tournament was coming up, I got a plane ticket to New York to a big ski resort up there in Lake Placid. I realized, “Oh my god, this is like one of these national, downhill skiing events. I’ve never had to do mics up a mountain before. How am I going to do this? Well, I guess I’m just going to have to figure it out.” And it was terrifying. But I did it.

RN: And how did you keep getting the freelance jobs?

JBS: I loved freelancing because you were only as good as your last job. In other words, if you didn’t do the best job, there was somebody else who was going to take that from you. I thought, “Let them have it. If they can do a better job than I can, that’s fine.” I got to know a lot of the TV directors and producers, and they would request me. I may not have been able to lift the most cable, but I was one of the best mixers out there.

Let’s Talk Rock and Roll

JBS: I started playing music in Gainesville, at the University of Florida. That’s when I met this whole, wonderful group of women, the Kampho Femnique Frothingslosh. [Kathleen “Corky” Culver writes about Kampho Femnique Frothingslosh (KFS) in “Sparks and Prairie Fires: A Memoir (Sinister Wisdom 93 (2014): 18. They were an informal women’s group that planned political actions with a lot of emphasis on fun.]

I was a guitar player who would play with anybody, but there were so many good guitar players and singers. I figured out that I’d better look into something else. That’s when I got myself a bass. I started playing bass because of that. And I would just play with anybody around the campfires, or the marching guitar band. I’d be there with my bass. Somebody was always saying, “Okay, JB, come on.”

The four of us just clicked. I mean, it was like puppies of the same litter. It was magic.

I started out with a washtub bass, you know, the string and the broomstick with the big washtub. I thought, “I feel this. I get the bass. I really get it!” There was just one string, and I could tighten it up or loosen it up, and play with all the other guitar players. I’m sure some substances were involved that made it seem really special, probably more than a Miller High Life beer. I went out and bought myself a little hundred dollar bass guitar and a tiny little amp. And I said, “I’m going to learn this thing.” And I did.

RN: You’re self-taught on bass?

JBS: Yes. Oh, it changed my life when I picked up a bass. I just knew that was for me.

RN: Did you go to Atlanta right after graduating from Florida?

JBS: Yes.

RN: And that was in 1974. Were you playing in bands before Moral Hazard started?

JBS: I was playing. I’d go to parties and things like that, yes. We Moral Hazard band members all kind of met each other, and it was just instantaneous. The four of us just clicked. I mean, it was like puppies of the same litter. That was another reason I decided to quit CBS. I really wanted to be a musician. That was my ultimate dream, to be a rock star. But I also saw that the money wasn’t there for me, and maybe not quite the talent that I needed. But I tell you, Moral Hazard came really close because we were so avant-garde, “out there,” that everybody was like the RCA Victor dog: “Hum? What is this? What is happening here?” I wasn’t a great musician, but I had the rhythm. And we just clicked, the four of us. It was magic.

RN: How did you meet?

JBS: We met through going to parties and seeing each other play. I’d heard Jan Gibson play, and heard some of the things that she did. KC Wildmoon was in a band called Anima Rising. [See Beth York’s essay “Consciousness-Raising with Anima Rising” in Sinister Wisdom 104 (2018): 15-25.]

We all ran in the same circle. That was when the Indigo Girls, Emily and Amy, were coming up. And Dede Vogt, and Pretty Good for Girls. There was such a musical crowd there, and wow, did I want to be a part of it. That was all I wanted to do. I also owned a house, and I didn’t like being downwardly mobile. So I really wanted to work, also. I had the television gig that I could do, and that was a great gift, being able to do it freelance. Even though I think it stopped me from really pursuing music because I thought about the money and travel, and doing other things. I kind of let that dream go by because I was trying to be realistic. I didn’t really know that I could do it on that scale. But I wish I had tried it more.

RN: Everybody remembers Moral Hazard, everybody in that scene. They have very positive memories of it. It was different in many ways, not only avant-garde, but you were doing theatrical stuff, too.

JBS: Oh, yes, absolutely. And the song-writing was just incredible. The images that we could put out there. Of course, most of it was Jan Gibson, but we all contributed.

RN: Did you write different songs?

JBS: We would collaborate with them. Jan would come in with a line, like “Wow, this is like a Talking Heads kind of thing.” She would have two lines that can portray an image in your mind. We would just sit and work out music with it, contributing a sentence here, a sentence there. KC and Jan were the main songwriters, but Jaen Black, the drummer, and I would set the rhythm and the music. KC would then do the guitar parts.

RN: When I interviewed Jaen Black, we listened to some Moral Hazard songs she had on her computer. We listened to about ten songs, and the bass has a prominent role in many of those songs.

JBS: Yes, Jaen and I had a psychic connection. She would get the beat going, and I would stay just enough on the back beat to make it interesting. The lines and everything, they allowed me complete freedom on that. The song “A Bomb Shelter,”the bass just drove that. I love that song. To this day, I can still play it. And “Bisexual Girl,” too. That was the other one. I loved how they’d let me start it, just kind of slapping the bass more than anything. Then we’d all rock into it. Oh, it was such a great feeling!

We had so much more to say than just the music.

In other words, we didn’t just want to play music.

We wanted to be able to incorporate messages with it, activism, and visual concepts,

not just all of us playing instruments.

RN: I’ve heard musicians like Keith Jarrett talk about that exact same thing you’re talking about. About how you would fuse, somehow, and how the group seemed to have a psychic connection.

JBS: Oh, you had to. You just really had to. I mean, I loved Keith Jarrett, and I love Jaco Pastorius, who played bass with him a lot, and wow! It gives me goose pimples to this day to think about when we really clicked it. And the live performances were magic to me.

With my engineering background, I did a lot of the sound for whenever we’d go to set up. We’d set up our own sound equipment. KC was very knowledgeable about that, too. It was really great because I could come in when we’d be playing bigger venues, and there would be a sound engineer there. I knew how to talk to them. We spoke the same language, and I loved doing that. I always tried to listen to us. I’d go off somewhere while they were playing and singing to make sure everything was how we wanted to it to sound.

RN: Y’all played with a theatrical group, right?

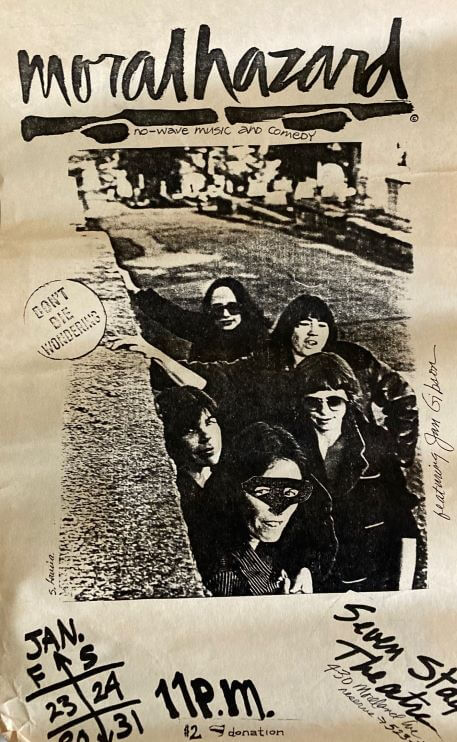

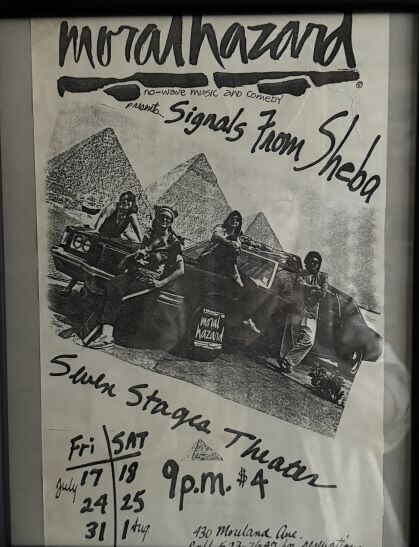

JBS: Yes, we played at Seven Stages, which was a theatre group. I’ve got some posters.

RN: What made Moral Hazard want to do theatrical things like “Signals from Sheba.”

JBS: We had so much more to say than just the music. In other words, we didn’t just want to play music. We wanted to be able to incorporate messages with it, activism, and visual concepts, not just all of us playing instruments. You know, music that people could dance to. We wanted to make it like a play, a musical.

Coming Out

RN: Tell me about coming out, and what connected you with all these other lesbians.

JBS: Again, it was the music thing. I had loved playing music in Gainesville with all the wonderful musicians that were there. Of course, none of us were doing it professionally. It was more like campfires, parties, and informal things like that. I don’t think any of us really thought about doing it professionally. But when I got to Atlanta, it was a big deal. There were the Indigo Girls, and Pretty Good for Girls, and there were just all these wonderful musicians up there. There was R.E.M., the B52’s, not just women musicians but a whole group that was all out, and they were performing. There were wonderful places like Little Five Points Pub, Eddie’s Attic, and all kinds of music venues.

RN: Those weren’t gay or lesbian, right? They were just regular bars.

JBS: Yes. The Moon Shadow, the Harvest Moon, and places where you might have an audience of fifteen people. Or you might have an audience at the Moon Shadow where they could handle a thousand people. I don’t know how in the world Moral Hazard got it. In fact, when Jaen and I were talking, we remembered some of the gigs we played, like Center Stage Theater, opening for the Washington Squares, and incredible venues like that. I thought, “How did we get there?” But it just all worked out. We got chances to play, and we took them. We really loved the theatrical, the more performance part, as opposed to just the music.

RN: For the performance, did you have lines? Did you have a script to go with the music?

JBS: Yes, we did. And we’d have a very loose outline of where we wanted to go with it. And yes, there were some very specific things we wanted to bring out. Some of the things that we did on stage probably weren’t good ideas, but we did it anyway. And then we would incorporate it into the music. We would then sort of break the fourth wall, go get our instruments, and then incorporate that into it.

RN: You know, it sounds like improv. That was big at that time.

JBS: It was, it was!

RN: Did you know Gail Reeder in Atlanta?

JBS: Oh, yes, in fact Jaen Black and I started a band with Gail Reeder on the side. We called it Tammy Whynot and the Even Strangers. That was it. We were Tammy Whynot and the Even Strangers. And what was really funny about that is Jaen and I developed these two personas. We were Chlorine and Tundra Landafille. I loved it. We were the Landafille Sisters. I was Chlorine and Jaen was Tundra.

RN: That’s great, Tammy Whynot and the Even Strangers.

JBS: Yes, and Gail Reeder was the lead singer on that. We were her backup band.

RN: Gail is interviewing KC. Beth York and Phyllis Free are part of this Herstory Project.

JBS: I know them, too.

RN: Tell us the last thing you’d like to have on your interview.

JBS: I’ve had such a wonderful life. I’ve been able to chart my course in many ways. I’ve had angels looking over me. There are not many things I would change. I think probably being a rock star would have been a lot of fun, but it might not have been. And then again, I believe in the fifteen-minute principle: if you’re not doing what you want to do for the next fifteen minutes, change it and go for it. If you can imagine it, you can have it.

See also:

Beth York, “Consciousness Raising with Anima Rising,” Sinister Wisdom 104 (Spring 2017): 15-25.

Moral Hazard, Step Over This Line, CD, ten songs, 41 minutes, available on iTunes and Spotify.

Rose Norman, “Moral Hazard: The South’s First Out Lesbian Band.”

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee and again edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.