Faye Williams – Growing Sisterspace

Interview by Woody Blue in Gainesville, Florida, on May 9, 2018

Woody Blue: Faye, were you raised in the South, and are you from Gainesville, Florida?

Faye Williams: Yes, right here in Gainesville, Florida. I grew up in what is called Porters Quarters. I graduated from Gainesville High School, GHS, in 1973, I moved to Tallahassee, where I went to Florida State University (FSU) for a year. Then I said to myself in 1974 that I had to get out of the South. “I got to get out of here. I got to get out.”

WB: Because?

FW: I got a scholarship to FSU, but I didn’t appreciate the racism. The racism and the sexism. I decided that it must be better up North, and I thought about going up to New York. It was to escape. You know, just escape the racism and the sexism and the homophobia.

WB: Had you gone up there before?

FW: Yes, I had a place to live. I have an aunt that lives up there.

WB: Were you out as a lesbian at that time?

FW: Yes. I mean, we didn’t talk about it, but everybody kind of knew that I was looking at women a whole bunch, and I had a whole bunch of women looking at me. They kind of made a deduction from that. Yes, yes.

WB: When you went up north, were you just escaping? You didn’t have a backup plan.

FW: No. I went to visit my auntie. That was it.

WB: Were you wanting to go to school?

FW: No. I never wanted to go to college. I mean, eventually I did, I graduated from George Washington University, in American Studies, and that was that.

WB: When you got to New York to your auntie’s, did you then find the lesbian community there? What was going on?

Biographical Note

Faye Williams was born in Porters Quarters, the historically Black district of Gainesville, Florida. From an early age, she loved to read, and she was driven by a strong commitment to social justice. She has worked for Black Liberation, feminism, peace, and LGBT activist organizations throughout her life.

Realizing her lifelong dream, Faye opened Sisterspace and Books in downtown Washington, D.C. in 1994. More than just providing a showcase for Black literature and authors, Faye created a meeting and forum space for the community. Evicted from the bookstore in 2004, they regrouped and reopened in another location for two more years.

Faye Williams continues her community activism. When she moved back to Porters Quarters, she applied her talent for drawing the community together in creating M.A.M.A.’s Club, a non-profit organization focused on “Music, Art, Movement, Action.”

FW: No, because I got more involved with the prison movement, and I decided, well, okay, that’s great, but I don’t like the cold. I came back home for a minute. I came back to Gainesville, just for a minute. Then I decided–it must have been in 1975 or ’76– that I would go back to Tallahassee. That’s where I met folks from the Feminist Women’s Health Center. That’s where I was able to really come out. I understood the politics of the feminist movement.

The Tallahassee Feminist Women’s Health Center

WB: Was that with Byllye Avery?

FW: No, Byllye Avery was here in Gainesville, but then she went back to Atlanta. She wasn’t part of what we did in Tallahassee, at the Feminist Health Center.

There was one in Atlanta but the original place was in California. Carol Downer [founded the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Los Angeles in 1972, and inspired] Linda Curtis, who cofounded the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Tallahassee in 1974. Linda later became my partner. (Laughing) But anyway, that’s another story. That’s the real news.

NOTE: Carol Downer cofounded the Los Angeles Feminist Women’s Health Center in 1972. “In Tallahassee, Linda Curtis and Lynn Heidelberg were as inspired by the Self-Help movement as they were incensed by the fact that local women were unable to get appointments with local doctors and were forced to travel up to 180 miles away for basic gynecological care. They traveled to Los Angeles to learn more about operating a Self-Help Clinic. In March, 1974, they opened the Tallahassee Feminist Women’s Health Center (FWHC) offering pregnancy tests, basic health information, and outpatient abortion services.” The FWHC still exists today.

WB: Where is she now?

FW: She’s in Texas.

WB: She started the clinic at the time?

FW: Yes, and Marion Banzhaf is still in Tallahassee. I moved to Tallahassee, and I wasn’t interested in school.

NOTE: “The Marion Banzhaf Papers document a 30-year span of Marion Banzhaf’s career as an activist in the women’s health movement and her work with awareness raising and the prevention of and care for HIV/AIDS among women.”

I started noticing certain people at certain protests and mostly folks from the Feminist Women’s Health Center because the anti-abortionists would show up every Saturday. I thought that’s where I’d go. I started protesting, started trying to make something happen. Eventually, they hired me to be in charge of their library.

The Feminist Women’s Health Center had a library. They needed somebody to take charge of the documents and the books. I did that for a few years. But really, in terms of becoming a feminist and holding on to that time, it really did come through the Feminist Women’s Health Center.

I’d already identified myself as a feminist because I was part of the FSP [Freedom Socialist Party] Socialist party. [The Freedom Socialist Party split from the Socialist Workers Pary in 1966, emphasizing issues of women, people of color, and sexual minorities.] I know of certain things, and I would challenge them with certain things, and we always get in a fight about something. I said, you know, how can we be struggling for Black liberation when I see exploitation and oppression of Black women in the socialist party? That’s not going to work with me.

Feminism, Black Liberation, and the Freedom Socialist Party

WB: Say it again. You’re struggling for Black Liberation…

FW: Yes!

Look, this is all great, but you’re not going to oppress me. You’re not going to exploit me.

You’re not going to hold me down for the Black movement because I’m part of the Black Movement.

WB: and how we’re going to get there…

FW: Right! Right. We’re all about uplifting Black folks. But I’m Black folk as well as a Black woman, and I’m not getting the same kind of energy, attention, and thrust that I needed to be a Black woman. I started challenging them. I said, “Look, this is all great, but you’re not going to oppress me. You’re not going to exploit me. You’re not going to hold me down for the Black movement because I’m part of the Black Movement.” I guess that was around the time Womanism and a whole lot of other words were being used.

It’s a kind of playing with feminism. It was sad because a lot of people didn’t understand what I was doing. We Black women felt misunderstood.

WB: Is that how you decided to put in your time with the Feminist Women’s Health Center?

FW: Yes. I appreciate the book that Alice Walker wrote about womanism. I appreciate Alice Walker, period. I want to hold onto the feminism term because when you look it up it means you support women politically, socially, economically, and culturally. What’s wrong with that? Nothing. That’s why I continue to hold onto feminism.

I want to be identified as a feminist, a lesbian, a Black woman, and many other things. I try not to change it because it becomes confusing when you use those terms like womanism and some other terms. I’m a feminist.

Washington, D.C., “That was heaven for me”

After five years, I decided that it was time to get out of Tallahassee. I went back up North, or the so-called “up North,” and I landed in Washington, D.C. That was it. That was heaven for me.

WB: You found your people.

FW: Yes, yes. Mostly through the Black community. It was really the Black community of D.C. When they show it on TV, you only see the monuments and a whole bunch of white folks. It’s a tourist site.

When I got there, I kept asking, “Oh, am I in the Black community?” They’d say, “What are you talking about? D.C.’s Black.” And I’m like, “Really?” Then they’d say, “Have you been to the City Commission?” “Nope.” “Well, why don’t you go on down and check it out?” Got down there, all these Black politicians, all these Black women activists.

That was it for me. That was my heaven in that moment. I learned so much, you know. I learned so much through Marion Barry. Don’t even get me started on that. He was my hero, and he was the mayor of D.C. You probably know him only through his smoking crack.

I can’t separate, you know, being a woman and being a Black person.

For me, it all comes together.

Marion Barry was the chair of SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]. That’s another story. But really, I just started following him and his program. I met so many Black women in that community, and they taught me. They’d say, “You’re new. You have to take time. You have to understand. You have to show us respect, and we’ll bring you into the circle.”

Eventually, probably about two years, I was brought into the circle. They trained me more, and they said, “This is what we agree on; this is what we disagree on.” And I said, “Tell me. What do you disagree on?” and it went back to feminism. “How can you be a feminist, how can you be a Black Nationalist, how can you be…?” I said, it’s the same for me. I can’t separate, you know, being a woman and being a Black person. For me, it all comes together. I’m not going to deny my Black Nationalism; I’m not going to deny my Black feminism. I lost a few friends, but I also gained because people thought I was basically crazy. If they were crazy, we could join forces. And we made it happen that way.

The Black Women’s Self-Help Collective

WB: It puts you into a smaller category with others to work with.

FW: Yes. And that was good. Because you knew exactly what they were about. We didn’t have to struggle on anything. Then we started forming different groups or becoming part of different groups. I was working for the Washington Women’s Self-Help Collective, and I was there for like nine months. And yes, this was a white group.

WB: Was it a Free Clinic?

FW: Yes, Part of St. Stephen’s Church. They hired me full time to teach self-help, and to teach women how to do breast exams and cervical exams. I talked about birth control. There were many forums about and around lesbianism and heterosexism.

After about nine months, I started noticing that most of the folks there were all white, and I said, “You know, I think we need to form a different group.” They gave me permission, and I mean in terms of commissioning me, to pay me, for organizing a group. I organized the Black Women’s Self-Help Collective. We were one of the first ones to promote and help organize the conference that Byllye Avery and others had down there in Atlanta.

WB: What years are we talking about now?

FW: 1982 to 1983. That’s still very early in the movement. Don’t remind me. I was out for a few years. That [Black women’s health] conference was held back in 1983, in Atlanta. After that, what happened? In ’89 I was going back to school. I had a scholarship for George Washington University.

NOTE: For more about the Black women’s health conference, see article by Betty Norwood Chaney, Black Women’s Health Conference, Southern Changes 5.5 (1983): 18-20.

Returning to College

WB: Something urged you to go to school.

FW: It had to do with being in therapy, and talking about racism. It just so happened that the provost for George Washington was part of that group. I didn’t know this guy, and I would constantly talk about racism and one day he just went off. (Yelling) “Goddammit. I’m tired of you talking about racism. It ain’t about racism; it’s just you’re lazy. You’re smart, but you’re lazy.” And I say, “What did you say to me? What do you mean, lazy?” “If I gave you a scholarship, you would not take it because I’m a white man.” Blah, blah, blah. He went on. I said, “I bet I would take it.” It was a weird back and forth. He said, “OK, let’s see. You got a full scholarship for George Washington University.”

I was shocked. I said, “What?”

“Yes,” he said. “You got a full scholarship. I’m the provost for George Washington University. You’ve got a scholarship.”

I said, “Really? You’re the provost?” and he said, “Yes, I am.”

I said, “What you doing in my group?”

He said, “Well, that’s a different story.”

I said, “OK.”

He gave me a full scholarship.

WB: Wow, what a way to get a scholarship. That’s really cool. What did you decide to take?

FW: American Studies. Yep, yep. American studies. Learn a little more history, you know, American history, with a focus on literature.

WB: You decided to go to school. Did you have living expenses?

FW: Yes. I had a full scholarship. Everything was covered. Tuition, books, expenses were all covered.

WB: Did your attitudes change in the university? What happened in the university?

FW: Yes. That was really a good experience for me because I didn’t know; I had not been around middle-class or high society white folks. The racism was everywhere. These were young folks, and I’m in my thirties, going back to college.

It really struck me when one of the students asked me, said, “Faye, what are you doing for Thanksgiving?”

I said, “What do you mean? What am I doing for Thanksgiving? I’m going to relax.”

“Do you want to go to Europe with us?”

“What?”

“Go to Europe with us? For winter break?” (Faye starts laughing, joking)

“I’m not going to Europe.” I say, “No, I don’t have that kind of money.”

“Oh, no problem. We’ll pay for it.”

I said, “No. I’m still not going, but thank you so much for that offer.”

WB: That’s quite an eye-opener.

FW: Yes. The money around me, the speakers they would bring in, the forums they would have, the travels, all of that. George Washington University. They would walk around with these nice shirts, you know, George Washington University tee shirts, meaning something.

I say, “What does it mean when you wear that shirt, what does it mean?”

“Well, that’s just part of our culture.”

“OH, ok, but it’s not part of MY culture. Have you looked on the other side of it? It’s not part of my culture. Let’s talk about George Washington. Did you know that he had slaves, did you know any of that?”

“No.”

“You don’t really know your history, but you’re walking around with it.”

Really, let’s get serious about this. It was all nice and friendly. I met the students as well as the parents.

WB: Did you have a group at the University that you could relate to? Feminist? Black?

FW: Yes. They had the Black Student Union. I was part of that. I was closer with the professors, really, like Maxine Clare. She wrote a book. I can’t think of the name of the book right now, but she’s a Black woman, and I met her through the English department. I just had friends, mostly professors. OK. Let’s put the children [the younger students] to the side.

WB: Because they were serious?

FW: Yes. Guess who was our keynote speaker, our commencement speaker? Hillary Clinton.

I said, “I’m not going to that ceremony,” and my father said,

“Oh yes you are. You are going because we’re coming up there. You’re going to graduate. You’re going to listen to Hillary Clinton.”

I’m like, “I’m not doing it. I’m not doing it. I’m not…I voted against her.”

Nevertheless, she was our commencement speaker.

WB: This is fascinating.

FW: I live life to the fullest.

Sisterspace and Books

WB: You’ve had a wonderful, colorful life and I’m really happy about that. You graduated, and now you’re back on your own. You’re an out lesbian having a relationship. This was well-known at this point?

FW: Yes, right. My partner, Cassandra Burke, opened up a consignment shop, and I was responsible for the marketing. We had no idea what we were doing. I said, “You know what? Let’s do it the old way. Make a flyer and put the flyer on everybody’s car.” We went over on Sunday and put flyers on everybody who’s at church. That’s how we got our customers. The next thing we know, we were rolling. We were rolling. OK. We didn’t have any money, but we made progress. People say, “Why do you put this flyer on here?” and then they say, “OK. I’m coming. I’m coming.” That’s the way it worked.

After about nine months, I started noticing women coming into the shop would have black eyes and scratches, you know, domestic violence. I said, “Cassandra, we can’t continue to just sell clothes. We got to speak to this issue.” She said, “You’re absolutely right.”

I said, “Let me bring in a shelf and a couple of books, dealing with domestic violence, women’s health care, just put something on the shelf that would at least slow them down a minute.” Then, we can approach them about what happened. Because when they’re shopping, they can’t really put a day at a bookstore. They can come this way.

The way we set it up, they had to pass by the books. Then they could stop and talk. Once we did that, probably like another month, we realized we needed to start setting up forums.

We thought, “OK, this is good thing.” Right? Can you imagine this? Right in the front of the clothing store we had a forum.

WB: A forum? Like a discussion?

FW: Yes, discussion and workshops and some women would come. First, we started with healthcare. Everybody who would be into healthcare. They would come, sit down and have a discussion, just for like an hour. It started out with like eight people and grew up to like thirty-five. I said, “OMG. We can’t continue to have a consignment shop as well as the forums.”

WB: This was on the sidewalk?

FW: This was in the store. We were moving clothes to the side, and we would be in the center of the clothes.

The universe heard us because the woman next door moved out, and we grabbed her position. We started having forums there and it went from like eight up to about fifty or sixty. We said, “OK. We got to really do something. We got to make this happen. It’s not about clothes anymore; it’s about saving our lives.”

These women who are coming are beat up. They didn’t want to call the cops for obvious reasons. I said, “Well, we can’t really AFFORD to get a new location. Let’s just stay here for a minute and let’s do less with the clothes and become more like a site for forums and speakers and for music.” That’s the way it happened.

My biggest dream was to open a bookstore.

One day I was passing by this building. I had noticed it for like three years. It was empty, and I said, “Let me take down this number.” Maybe we can afford it now.” I called this guy, and I said, “Can I see the building?” And he said, “Yes” and he came, and he said, “What you want to do?” I said, “We really want to open up a bookstore.” He said, “You’re not going to make any money on bookstores.” He didn’t know that Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Terry McMillan, they had won all the awards that year. Everybody was buying books, you know, Black books, Black women books. “Well,” I said. “I think so.” I said, “If we just have a space.”

This was 1993 or 1994. The bookstore opened in ’94. Because we recognized we could make more money by selling books rather than clothes. It never did fit us. We just wanted to be there for women. They started saying, “Well, OK, can you order this book for me?” And I said,” We’re not a bookstore. They said, “You should be.” OK. OK. OK. OK.

We had another forum and everybody was in the circle and that was the one when we talked about dreams. “What would your dreams be if you could make something happen? What would be your biggest dream?”

My biggest dream was to open a bookstore. I put it out and everybody applauded, and I assumed that they all wanted to be part of the bookstore. That wasn’t true. They just wanted to shop. They didn’t want to help me organize it. They just wanted to come by and shop and have the discussions and meet some women but that was about it. I said, “OMG. What have I got myself into?” We got the building and then I started making phone calls, and it was very disappointing, because nobody wanted to give me credit. I didn’t have any credit and I couldn’t get credit, but I wouldn’t give up. I went to the library and said, “Is there a book or something that can tell me how to open up a bookstore?” They said, “Yes, Yes. There’s a directory for books.”

“You call all these numbers.” I mean it was about 200 numbers. Every day I would take about twenty. I would call and say, “I don’t have any money, but I want to open a bookstore.” Most of them would just hang up on me. That was that. When I got to Random House, there was this brother and I told him. He’s a Black man. It was very seldom to get a Black person on the phone. His name was Manning Barron.

I said, “Tell me. What is it that you do?”

He said, “I’m the guy who goes around the country and I provide Black books to all the bookstores, like Books-A-Million, Barnes and Noble.”

I said, “Oh OK. I’m trying to open up a bookstore. Can you help me?”

He said,” Yes, you need $50,000.00, and you can go from there.”

I said, “Come on, Brother, you know I don’t have $50,000. Is there another way?”

He said, “No, there’s no way and I really have to get off the phone.”

I said, “Could I have your private number then?”

He said, “I don’t know why you want to call me because I’m going to tell you the same thing.”

said, “Just give me your number, please. Give me your extension. You know, and I’ll call you every day.”

By the third week, he said, “You have worn me out. I’m going to see if I can get you a credit for Random House.”

I said, ‘Please, please, please, please do it. Please do it.”

He called me three days later.

He said, “You have $45,000 to $50,000 credit at Random House.

I said, “Does that mean I can order books from them?”

“Yes,” he said. “Once I hang up the phone, I’m sending you a fax, I’ll send you a form, fill it out, put my name at the bottom of it, and you can order books.

Boy, that was it! All the books we had were from Random House. Someone walked in and said, “Oh, you got all the books from Random House. How about Harper Collins?” “Hey, you know, you’re right.” Being arrogant, I called Harper Collins and I said, “I’ve got about $45 or 50,000 credit with Random House. Maybe you can let me get some credit from you.” “Oh, sure. No problem.” That’s how the bookstore started. We had the bookstore from 1994 to 2004.

WB: You know how to work the system.

FW: That’s right. But really, it was the people who made it work. It was the Black women. It was the white women. It was the feminist movement. It was the people who did not identify as feminist who made sure that Sisterspace survived.

WB: You got your stuff and you stocked your store…

FW: Then I got speakers. That was a big problem, to get authors to come and speak. I called the publicists who were sending them to all the white bookstores, even to independent, white bookstores, but not to Sisterspace.

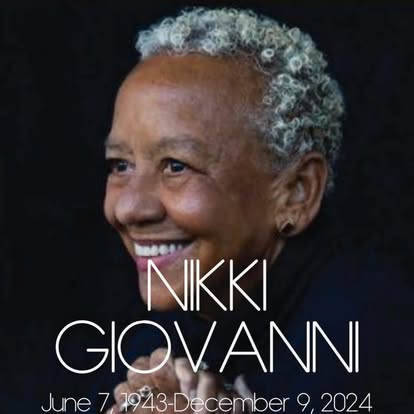

Once I got Nikki Giovanni, then I got Alice Walker. I got Toni Morrison. I got everybody. Everybody who came through D.C. had to come to Sisterspace.

One day, I got pissed off. Nikki Giovanni was speaking down at the Archives in D.C. I went down, and I said, “You know, sis, I own a bookstore and I talked to your publicist at least twice about sending you to Sisterspace. She said “It’s not on my list.” And I said, “Yes, that’s the point. I’m not listed on your list. Can you do something about that?”

She said, “Where’s the store? I’ll be there in two hours.”

I said, “Two hours. I don’t have the books.”

She said, “Well, what are you complaining about?”

I said, “Well, I didn’t know you would come.”

She said, “I’ll tell you what. Here’s my number.” She gave me her number.

She said “Call me when you get back home. We’ll set it up and you better have some books when I come back from Virginia.”

I said “Absolutely.” She was my first big name speaker. Nikki Giovanni.

WB: How long did it take you to get to that point once you started the bookstore?

FW: I think it was about four months.

WB: You got your speakers and Nikki Giovanni. Wow.

FW: Once I got Nikki Giovanni, then I got Alice Walker. I got Toni Morrison. I got everybody. Everybody who came through D.C. had to come to Sisterspace. It was just a great honor to have them, to listen to them, to have the kind of audience, you know. It was too big for the bookstore, and we had to rent out spaces at the university. We had Angela Davis at the University of District of Columbia. We had bell hooks. Should I go on, bragging about all the authors we had?

WB: If you got a speaker, say, Alice Walker, you have to rent out space because she’s a big speaker. What’s the fee to get in? How do you get the audience in there?

FW: Right. First, we would ask them to purchase the book from us. If you decide you want to purchase the book from someplace else, unfortunately, like Amazon or an Indy white bookstore, and you still want to hear her speak at Sisterspace, then we would charge you $10 to come in.

WB: All you had to do is buy a book from you or pay $10.

FW: Exactly. On top of that, we never discriminated against anyone if they didn’t have money. If you didn’t have money, we never said no. We always invited them to come. We’d advertise it that you need to have $10. Most of the time people would give us something extra. They would give us $50 “just because.”

WB: Also, white women were beginning to understand that we need to connect.

FW: That’s right. Two white women were the strongest people, the strongest white folks, the strongest white women who supported Sisterspace. They made sure all their friends understood it.

WB: Did they live in D.C.? How did they support you?

FW: Yes, they did. They supported us and they came to all our events. They bought shirts, like our “Sisterspace and Books” t-shirt. We had a book-signing with Judy Witherow with her book. They were just… we were sisters. We were feminist sisters. That’s the way a feminist sister acts. It makes it easy. At the same time, they were encouraging their white friends to support Sisterspace and Books, telling them, “Don’t be scared. Faye is a little loud. Sometimes, she doesn’t want to talk to people. You know, she’s not sociable sometimes. But keep in mind, it’s a business. She’s trying to make it happen. You don’t have to be friends with her, but come out and support the bookstore.”

It still happens here, in Gainesville, Florida. “She’s not the friendliest person.” No, that’s not really my program. I have friends around me, the people I want to be friends with, like you. You’re my friend. But, you know, I don’t have to be friends with everybody. I can’t. I don’t have that much energy. I’m one woman. I have to remind myself that sometimes that I can’t be friends with everybody. I can’t be friends with every Black woman.

WB: You hosted speakers who wrote books. Are there other events that you held other than signings?

FW: Yes, we mostly made our money from conferences. Any Black groups or women’s groups, when they would call Sisterspace to set up as a member, we were the only bookstore. For most of us, that’s the way the money came in.

WB: You helped those groups.

FW: Yes. If bell hooks was speaking at the Convention Center, she would say, “I need to sell my books, and the only bookstore I’m working with is Sisterspace.” She would say, “Did they call you?” She would call me and say, “Did they call you?” “Yes, they called.” “Will you be there with my books?” “Yes, we will be there with your books.” That’s the way it worked.

WB: Black authors promoted you, and they needed you.

FW: Not only Black women authors. The white women authors as well. We had Barbara Ehrenreich.

WB: As a bookstore, you went to conferences. Did you go to other events besides conferences?

FW: Only if they were located in D.C. I didn’t travel a lot. And didn’t want to. You know, people would invite us to NOW [National Organization for Women] to sell books, but I’d say, “I’m not doing that. Thank you for the invitation, but no. I kept mostly to D.C. and to Virginia.

WB: Did you also stock all those lesbian periodicals, Sinister Wisdom, Maize, off our backs, lesbian newspapers, and the feminist newspapers?

FW: Yes. Sure. It was up front. They created many discussions and arguments. I would love to hear the women’s arguments. ”Why do you have off our backs here?” “Oh, you read off our backs? How do you know about off our backs?” “Oh, you’re new to Sisterspace. How do you know about off our backs?”

“Well, my sister. She was reading it, and I thought I’d take a peek.”

“Oh, are you saying your sister’s a lesbian?”

“Well, you don’t have to announce it, Faye. Yes, she’s a lesbian”

“Is that why you’re here? Why don’t you just say that? Why you upset? Come on, make it happen.”

And then we would sit down and have a full discussion.

“How do you support your lesbian sister?”

WB: Could you tell me certain issues that were particular to a Black bookstore in D.C.?

FW: Yes. Let’s see. You mean in terms of being accepted by the community? We were on 14th and U., and that is a major location. It’s close to the White House. It’s downtown. That’s the spot. Everybody wants to be at that spot. We’re not dead yet.

WB: And that’s where you were.

FW: Yes, for ten years.

WB: Did you attract people from the Black community that probably would never have gone into a white store, and their eyes got opened?

FW: Yes. They would come from Baltimore to shop at Sisterspace. They would come from New Jersey. All day long, they’d come down from New Jersey. They were really proud of Sisterspace. They would come and say, “I wish I could open up a bookstore in New Jersey.” We encouraged them, but they didn’t have the money, and they wouldn’t have the same experience.

Then, one of the issues was that because of AIDS, HIV, and sexually transmitted diseases, we started focusing on that, especially with the young folks. A couple of the preachers would come by and say nasty comments to us. One day, I got pissed off and I went to the church. I stood and I waited till everybody was there. I stood up in the church and I said, “If you come back to my bookstore, I’m going to out you.”

WB: You said this to a Black preacher?

FW: Mm hmm.

WB: In his church?

FW: Mmm hmm.

WB: On a Sunday?

FW: Mmm hmm. Yes.

WB: Oh, boy.

FW: Because he thought he was doing something when he came to the bookstore saying “You’re nothing but a lesbian.” I say, “Yes, and proud of it. I’m going to visit you. And the next time you come down here, I’m going to out you.” Now, I just left it at that, to let everyone wonder “What does she mean, “out” him?” They already knew he was gay. Why are you allowing this guy to be your preacher, your “Jesus man.” I told him, “Don’t you dare come back to our bookstore and try to challenge us.”

Yes, in that church. I left shaking. Nobody attacked me as I was going through the door. They were in shock. They were in shock. They were like, “What?” You know, those kinds of issues. We had a couple of them.

WB: Did you know if other people in that church knew?

FW: They couldn’t wait to come to the bookstore. I think he left nine or ten months later. They got a new preacher. He resigned for some reason. We had to stand up, because if we had taken that, the other preachers would probably have done worse. They were already talking about us. “Don’t go to Sisterspace,” and just putting us down. At some point, you just have to fight back.

Nobody really wanted to deal with folks who had HIV, you know. Say, “That’s what you should be focusing on. Not the fact that we are lesbians and feminists and own a bookstore. Now have you set up anything in your church to talk about what’s happening in our community?” I think after he left–probably about a year later–they did set up a forum with the Walker Clinic that dealt specifically with HIV folks. We saw some progress. Overall, I was just so happy living in D.C.

WB: You’re ecstatically happy in Washington, D.C. for 10 years. What happened with the bookstore?

FW: We were in that building for seven years. The address is 1515 U Street. We were paying $2500/month for that building. It was so-called “cheap,” for D.C. By the third year, we realized that the landlord would not come out and fix the air and the heat. The contract said the landlord is responsible for that.

We got angry. Well, I got angry and I told my partner, “we’re not going to pay him any more rent. She said, “You’re crazy. The man’s going to put us out.” She calmed down. She said, “You’re absolutely right. We have to pay rent; we can pay it through escrow.” The money was in the escrow account, but he was not able to use any of it. This went on for like, another year, and he filed a suit against us. But we were smart. We kept him in court for seven years. He didn’t get any money. We would pay our rent into the escrow accounts. All that money was in the courthouse.

WB: And that’s the first seven years?

FW: Wait. We were in that building for seven years, and we kept him in court for four or five years. The money was in the escrow account. We couldn’t use it. He couldn’t use it. We were happy because we didn’t miss anything but our rent. We knew we’d have to pay that. We paid that. Folks started gathering around us because we would tell them, “We’re in court.” They said, “Why?” I said “We keep complaining about the air conditioning and the heat. We can’t afford to fix that. We’re hoping that our landlord will take us to court, and I’m sure the judge will rule against him and in our favor.” They said, “Good. Good idea.” We kept that going.

Finally, it got in court. We lost because we had transferred everything from Sisterspace to … what was it called? There was a senior center right next to Sisterspace. They had a big room. They allowed us to put extra books there, some storage space. There was a big flood up top. We lost everything.

Everything was lost. The accounting, all the books showing that we were paying him. All the receipts. We went in with stuff but you couldn’t read the bottom of it, the numbers, all of that. Even the judge was about to crack. He said, “You know. I know what Sisterspace is about, and you’re doing a great job. But I have to rule against you only because you don’t have the documents.

We had attorneys from the largest firm in the U.S. We had three firms. Each one of them took us on pro bono. That’s how we were able to stay in court for all those years because they didn’t charge us anything. They were proud of Sisterspace.

WB: The judge ruled against you?

FW: The judge ruled against us and said, “You have to leave the space,” and it was devastating. “You know, you’re going to have to throw me out because I’m not leaving.” “We will throw you out.” “Well, ok. Try. Do it.”

Don’t you know, the day my mom was visiting me on her vacation, here come the marshals. I said, “OMG. OMG. OMG. Not the marshals. I say, “Mom, Stay calm.” She says, “What did you do now?”

“Mom, Stay calm.” She was back there counting the money. We had a big event the day before. I put her over at the table and let her count the money. You know, make her happy. I said, “Mom, put all the money in the bag and stand up and you walk out the door. The marshals are here. I’m not walking out. They’re going to have to drag me out, ok?”

She did. I got one of the guys who was passing by and I said, “Come here. Get the rocking chair and put my mom right next to the church. The Freedom Church. Right next door to us. Put her right there in the yard so she can see what’s going on.”

By then, everybody had started gathering because they saw marshals out there. They said, “OMG, it’s time.” I called WTFW [a public radio and jazz music community radio station], and I said, “The marshals are here. I need folks to come down and protect Sisterspace.” Well, within twelve to fifteen minutes, we blocked the street. It was something. I was thinking, “Wow, this is really happening, huh? This is really happening. Really happening.”

Nobody wanted to get rid of Sisterspace.

WB: What happened next?

FW: They say, “You have to leave.” I said, “ok.” I sat down, and one man pulled me out. I’m not walking out. They pulled me out. That’s what they did.

WB: They didn’t arrest you. They just pulled you out of the building.

FW: They wanted to arrest me, but they were a little scared because we had such a crowd. And they were very angry. They wanted to beat up the marshal. I said, “No, stop the violence. We don’t do the violence thing. Just be here for a minute. Now what we have to do is get trucks.” People started calling different radio stations. They put us on, and people started showing up with trucks. There was storage space right down the street. We were able to put everything in the storage space.

WB: The marshals let you do all that?

FW: Well, no. They were really upset because there was a Black woman who was a marshal. She had no idea she was coming to Sisterspace, and when they pulled up, she said, “Oh hell, no. You can fire me, but I will NOT, I will NOT enter Sisterspace. She got in her car and left. She said, “No Way.”

The marshals went to get the labor guys on the corner. The day laborers. They came. They said, “What? Are you crazy? We’re not going to put our sisters out.” They were shocked. Nobody wanted to get rid of Sisterspace. They had to go somewhere else and find some guys who didn’t know about Sisterspace.

By the time they came back, we sat there, and we said, “You know what? Let’s let them pack up everything. We don’t even have to pack anything. Let them take their time, packing into these boxes. We provide the boxes to them. Let them pack up the boxes. Let them bring them out of the store. Then we’ll put it all in the truck and take it to the storage place.” It worked that way. They would pack it up and we would take it down to the storage place. It took maybe an hour and a half.

WB: Wow.

FW: Ain’t that amazing? That’s the way it worked.

WB: And it worked because your community came out.

FW: Yes. Then, I had a book signing. I said, “Oh, oh, Charles Ogletree is speaking, down at the law firm.” Do you know Charles Ogletree? He was the attorney for Anita Hill. I said, “Charles Ogletree is speaking. Leave those books to the side.” And Momma said, “You are not going to a book signing now.” I said, “Yes. Help me. I can’t do it by myself. I’m a little upset right now.” I got four people who volunteered along with my mom. She couldn’t believe I was doing the book signing. I said, “You have the money?” She said, “Yes, I’ve got the money. I said, “We’re going to do a signing down at this law firm for Charles Ogletree,” and we did it. I showed up. He said, “Hey, you got evicted. I can’t believe that you came down here with books.” I said, “Yes, I’m a businesswoman. I’m a businesswoman. I’m going to be here.”

He sold out all of his books. Sold out. Everybody was saying, “I can’t believe you’re here, Faye, but thank you, thank you, thank you.” Because we had worked so hard to get this guy. Everybody loves him. I didn’t want to disappoint them, and I didn’t want to disappoint myself.

After that, I took two weeks. I was really strong. I cried at night and just tried to be active in the community. Then it hit me. I realized that I couldn’t function for a few months. I couldn’t function. That’s when Sisterspace ended.

You always take the strongest ones first. And then, everything else comes down.

We were the strongest, the strongest ones on that block.

Because it’s the system, the white system. The white exploitive system that prevents marginalized people from owning businesses, housing, and everything else that we need.

Because we were an example. Once they shut us down, then they were able to scare everybody. Intimidate them. Everyone in that whole neighborhood.

There was an apartment right behind us. It was mostly Black and Latino women and their children. They were part of the lesbian, gay, and transgender community.

They wanted that building. They wanted that building because it was some very nice apartments. They wanted to make condominiums out of it. We had to struggle with them for like two years.

And they got it, once they got rid of us, of Sisterspace.

To show you an example of what they did. There was an apartment on the other side where people lived who had emotional breakdowns, mostly Black men. People who couldn’t find jobs, drug dealers, and all of that. They changed the land ordinance so that the park would be a dog park. Those men were stuck into their apartment all day long because they didn’t have a place to go.

We kept pointing this out. “Please don’t do that. Do you understand that these guys can’t go anywhere else? They have caregivers. They’re old men.” And they didn’t care. They wanted it because it was convenient for them and because they had jobs, federal government jobs. They could catch the subway in the morning. They would walk their dogs. They had to have a place for their dogs to shit and pee and whatever else you do with your dogs. They had to have a place, and they decided if they organized a group, changed the ordinance, and made this a park for dogs, everyone could just forget about the Black folks over there in that apartment. They had total control of that little community with the dog park and then the condos.

As soon as we left, there was some kind of way they were able to contact the landlord and convince him to do something because a lot of people got evicted from that place. People that had been there for like twenty years.

WB: Is this the gentrification of that neighborhood?

FW: Yes, Yes. Oh Yes. But it could have been handled differently with the gay community because they knew me, and they knew what we were about. But it was their white racism, the racism that came out. They needed that space, and it was beautiful. You know, every time I went up there, I would just stop by and look at it. It’s right on 16th St. It leads you right to the White House. But they got rid of those Black folks. I would ask them, “What happened to the folks that moved out?” No one had any idea.

WB: Would you say that Sisterspace was the glue that was holding that together, keeping your community space?

FW: Absolutely. That’s right. Absolutely.

WB: Once Sisterspace was out, the rest could crumble.

FW: That’s right. You always take the strongest ones first. And then, everything else comes down. We were the strongest, the strongest ones on that block.

WB: And you had been there for ten years.

FW: Right. Exactly. It could have worked the other way. But it didn’t.

WB: And if you had not had that flood?

FW: We would have won. What the landlord [for Sisterspace] wanted to do was to sell the building. We raised $1.8 million to purchase that building. He would not take the money. He would not take the money. That gives you another example of how much people appreciated Sisterspace being there. $1.8 million? We raised it. Yes. We raised it.

WB: You asked to buy the building?

FW: Yes. Exactly. We raised it. It started out that he was asking for $1.1 million. He would raise the price, thinking we would give up. He would raise it, and one of those times, we said, “This is the last time we’re asking you to sell us the building? $1.8 million is what we have in the bank. Do you want to accept this money, or do you not want to accept the money?” He said, “I’m not accepting it.”

WB: That was before the case was decided?

FW: Yes. We were thinking if we could own that building…

WB: It wasn’t about the money for him.

FW: No, it wasn’t. The whole story of Sisterspace needs to be documented. I mean, somebody has got to record it. I’m leaving out so much. I have some tapes; I can show you the tapes and some of the interviews we already had.

WB: You can donate all that stuff. You can copy it, and have it for the archives to preserve it so that people can access it.

FW: I want somebody to make a documentary on Sisterspace. Do you realize what I’ve been collecting for almost sixty years? I have that Black Panther newspaper. I have feminist and gay stuff. I have so much.

WB: What was next after the bookstore closed?

FW: I said, “Oh, it’s time for another Sisterspace and Books. What about another building?” I don’t give up. I don’t give up. Well, you know, I couldn’t give up. You know, there’s a song by Yolanda Adams. It says, “Don’t give up. Don’t give up.” One of my favorite songs. I decided I would reestablish Sisterspace and Books. Everybody told me, “Faye, let it go. You can’t do it.” And I said, “Watch me. We’re going to do it.”

Everything had changed in the publishing industry.

They were not sending out Black women authors anymore.

We were able to get another building on Georgia Avenue, which is close to Howard University, and that was a good spot. But so much had changed. Even over those two years a lot had changed. A lot of people left D.C. Either they lost their jobs, or it was part of all the politics in D.C. It didn’t flow easily.

People didn’t have a bunch of money to come and spend for books. It was a small place. In the first Sisterspace we had 2000 square feet. That was pretty good for a bookstore. The second one was maybe about 400 square feet, and that was not really on the same level. Plus, the second store didn’t have the kind of parking that we used to have at the first Sisterspace. At the first Sisterspace, we were right there close to the subway. People could take the subway. They didn’t have to worry about parking.

This spot, you had to drive, and that had a big effect on the bookstore. I was still able to provide books for conferences and conventions, but I wasn’t able to get authors to come back. Everything had changed in the publishing industry. They were not sending out Black women authors anymore. They had to pay to come to D.C., and spend their money to come for a book signing. That was in 2006.

Return to Porters Quarters

WB: Things had changed that much?

FW: Yes, things had changed a lot. I was happy with the fact that we were able to have forums and have conventions and conferences, but it was totally different. Eventually, I decided that this is not working. My bones were saying, “It’s time for you to go home.” You know that cold weather, yes, yes. Cold weather is touching these bones and time to go back South.

It took me two years to make that final decision. Would I come back to Gainesville, or would I go and live with my friend down in Miami? I never liked Miami. Plus, I needed to go back home. I needed to come back to Porter’s because that’s where I grew up. I wanted to continue to be active in many ways: politically active, socially active, and so on. And I felt I might have support here.

When I came back, people kept saying, “Why would you move back to Porters?”

I said, “Why? Why are you saying that? I don’t get it. Why would I LEAVE Porters? That’s the question you should be asking. Don’t you understand that the University of Florida and these developers want Porters? Do you understand that every time you put Porters on the Internet, it’s the first thing that pops up? Porters Quarters? Do you realize that you’re living on prime property?” That’s the reason I wanted to move back to Porters, so that I can be part of stopping the University of Florida from taking our land.

Most of the people who live over in Porters right now, folks who are [homeowners]… There’s sixty houses over there, and they’ve already paid their mortgage. They own those houses. We’ve got three landlords. Three landlords, and 57 percent of the houses are owned by the people who live in them. Developers constantly are knocking on their doors on Saturday, and asking “Do you want to sell your house?” They all say the same thing, “Do you see a sign in my yard? Hell, no. I’m going to die in my house. I’m going to die in my house.” Get proud of living in Porters. These are people who came from the projects, who were able to work and to pay the mortgage. They’re proud of living in those gray houses.

WB: Are you living in your family house?

FW: No, I live behind my mama. My mom still lives on a corner, right across the street from Porters Community Center. I’m leasing from my landlord; our house used to be across the street from her. It’s a Black woman, Jamie Williams. She was a principal. You see her around. She’s done a lot of stuff in Gainesville. I’m leasing from her, hoping that she’ll be able to sell me her house, that house, or even the corner house.

The guy said, “Well, if you have the money in about a year, you could purchase this house.” I said, “OK. That’s my goal. To raise the money, and purchase a home over in Porters because we see what’s happening.”

The University of Florida’s program is to knock down those houses and make it a parking lot for the Cade Museum, because they don’t have enough parking. They’ve already made a brochure instructing their students, “You walk on the sidewalk from 13th St. When you get to 3rd St, you make a right turn, then a left turn to Depot Ave., and then you’re right there at Cade Museum.” In other words, don’t go through Porters. Don’t talk with the people who live in Porters. Stay on this street, and it will take you right to Cade Museum. They told them that even in orientation.

WB: Why are they doing that? Why would they not want any contact between Porters and their students?

FW: Well, Porters, Black folks. They’re students. White students. Plus, they say, “You need a safe place.”

WB: They don’t want you to have any alliance or friendships.

FW: They don’t want any friendship to happen. Some of the white students who are coming through Porters, maybe the guys on the corner would say, “Oh, are you a student?” Maybe they’d have that kind of conversation. They don’t want that to happen. How’s that creating a problem? Just simple stuff like that really indicates what the University of Florida is about.

WB: What happened when the Black woman got upset by it?

FW: Oh, she just called and told me. She said, “I don’t know what I can do about it, but I ain’t calling anybody to come over to Porters.” She said, “If I’m out walking, I’m going to bring them through Porters. Then I’ll call you and I can let you know we’re coming over so you can talk to them.”

I said, “OK. I’ll be happy to do that.” Let them pass by the Porters Community Center. Why can’t we just have a stop here? Introduce ourselves and let people know we’re available. We can volunteer. We can be tutors. We can…

WB: When you left to come back here, you left everything up there. Your whole life.

FW: Except my books. I wanted my books. I got all my books in my house. I’m going to have to start selling some of them. Especially the signed copies, Toni Morrison, Angela Davis.

WB: Looking back on all of this incredibly rich information, are there things you would have done differently? Are there things that make you super proud?

FW: I guess if I wanted to give a story, this is one way. I didn’t realize this until I got into therapy. Why did I need to have a bookstore? It came out that when I was growing up over in Porters, when the bookmobile would come from the library into Porters. My best friend was a white girl, Carol. They would allow her to go inside of the bookmobile to choose her books. (Faye getting emotional.) Sorry… (heavy sigh)

We were friends, you know. She lived right across the street from me, by S&S Cleaners. I lived on the other side. We became friends because we both went to Kirby Smith [Elementary School]. Ha ha, the Confederate school. [It’s named for a Confederate general].

To be an owner, to be recognized as a leader,

to be brave enough to be an out lesbian feminist, a radical feminist

We were best friends. The bookmobile would come over. She was able to go inside. But as for me, they would hand me my books. I could not choose. I could not enter the bookmobile. This is the Alachua County Library system. I was discriminated against.

WB: How old were you?

FW: I was in fifth grade.

WB: You would have to read whatever they gave you.

FW: Right, which was kind of good. They gave me books. I didn’t have the vocabulary in fifth grade, but they taught me the vocabulary. It was on the high-school level reading. My friend always said, “We’ll share books. Read my books.” We read our books, and we would share our books with each other.

I guess at some point you have to suppress stuff because it hurts so much to remember.

When I had the opportunity to open up a bookstore, the first speech I gave in that bookstore was about that. I told them about the bookmobile and I said, “I promise, that one day I’m going to own a bookstore and I’m going to make sure that ANYBODY AND EVERYBODY that wants a book will be able to have a book from my bookstore.” That’s years later, years later. It comes back and I own a bookstore. I had no idea that it would come to me but I didn’t want to focus on it because it’s so painful. I would just say, “OK, let it go.”

Then the opportunity, the chance to own a bookstore meant so much to me. It’s not just that I like to read, but to OWN something, that I was denied the opportunity in Gainesville, but I could do it in D.C. To be an owner, to be recognized as a leader, to be brave enough to be an out lesbian feminist, a radical feminist, to make the kind of friendships that I’ve made over the years, to be able to travel to Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Jamaica. All of this as a poor woman. Still poor but able to travel and communicate with people, and it all comes from loving people, loving humanity.

Because it’s not always that you see progress. It’s not always about money. It’s about the kind of friendships that you form along the way, and what you put out comes back to you in many different ways.

My story is just to be open to everybody and everything, and let me see how it flows. That’s served me well. That serves me well. I’m proud of the fact that people from D.C. still call me, and remind me. They say, “Miss Faye, do you remember when you gave me that book? I just want you to know that I’m a lesbian.” I would say, “I don’t know. If you didn’t tell me all of that because I don’t know.” They say, “Well, that’s when it started, when you gave me that book about Barbara Smith. Remember that book you gave me?” I say, “No, I don’t remember.”

You know, having that kind of impact. To let people know it’s OK. You don’t have to commit suicide. You don’t have to run away from your family. You just have to be brave enough to say this is me. This is what I’m about. You can accept me or leave me alone.

I had those kinds of experiences. Especially with the young women, the young Black women because they needed more leadership in D.C. They need the same thing here. The same thing is happening here.

They call me. I say, “Come over to Porters.”

“No, somebody may see me.”

Well, that’s OK. Then meet me up at Bo Didley Plaza to go get lunch. We’ll sit down and talk there. It’s been something. My life story. Many things happened.

WB: You worked so hard for your identity as a feminist Black lesbian. Where do you see the future…good? Bad?

FW: I’m so proud of the young folks. It’s almost like you don’t even have to say, “I’m a lesbian; I’m a feminist.” It comes out. When you sit down and talk with them, they really get it.

My concern is they need to know our history because they’re moving forward without knowing our history. If they knew our history, they would have more Sisterspace and Books. They would have more. That’s not happening because they don’t read enough, number one. We don’t have the same kind of forums.

We had a meeting over at M.A.M.A’s Club. [Also called Mama’s Club]

[M.A.M.A’s Club (Music, Art, Music, Action) is a community center that Faye Williams started in 2017.

I said, “You know, back in the day we used to have an agenda, and then we’d meet.”

They say, “Ms. Faye, we have an agenda. It’s on the phone.”

“What? Let me see.” Their agenda was right there.

I say, “Oh, OK.”

I just sat over in the corner, listening to them talk, and they were ready. They were organizing around the Richard Spencer event [Spencer is a neo-Nazi white supremacist speaker]. Lesbian, gay, everybody in Mama’s Club. They met like three times there, and they organized. “I don’t see any papers. I don’t see any books.”

“Oh, we read at night.” “Read what?” “It’s on the phone.” I say, “Everything’s not on the phone. C’mon. You really need to start reading some bell hooks. You need to read Angela Davis,” “Angela Davis is on our board.” The board of the Dream Defenders. [Dream Defenders is a youth-led Black organization with groups all over Florida, including Gainesville.

“OK, that’s good, that’s good. But still you need to read all of her books. I’m sure she’s inside. You need to read, read, read, read, read. Even if you’re not reading her books, you need to just read, read, read.”

I’m feeling optimistic. I’m feeling happy. I see the vision. A lot of people complain about the younger folks, but I see them. I see the revolutionaries. Right in front of us. We got to support them. We may get upset with them, but we still got to support them. Because people got upset with us. Let’s just support them as much as we can.

Then, when we have to shut them down, let’s do that too. Because sometimes we have to say, “No, no you just can’t not work.” They give you a tone of appreciation once you shut them down. They may be mad at that moment, but my experience is that two or three days later they say, “Ms. Faye, we understand what you’re talking about. We promise you we will not do that.”

I’m not about violence. Going back to [the action against] Richard Spencer, “No, you cannot go out and create bottlenecks because of Richard Spencer? No, no, no, no, no. Because it comes back to you. You will be arrested, and then we have to go and bail you out. It affects the whole community. Don’t do that. I’m honored that they even allow me to be in the meetings.

WB: What are your future plans?

FW: My future plan is to relax at some point. I don’t know if that’s going to happen. But they say, along the way, you’ve got to relax. I say, “OK, I’m relaxing right now.” This is it for me. Beyond that, I don’t know.

WB: I guess my question was really, “Are you going anywhere with M.A.M.A.’s Club?

FW: Oh yes. It’s coming. We’re going to get that building. That’s become our community. People who went to the city commission meeting; people who testified, the people who were meeting with the city commissioners individually. I got to get one more nonprofit to come in with me and we’re now going to be able to pay rent. We have to be responsible for the utilities, plus we have parking. It’s going to happen.

WB: And it’s right downtown.

FW: It’s coming back. Yes, it’s coming.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Woody Blue, “Sisterspace and Books,” Sinister Wisdom 116 (Spring 2020): 62-66.

Feminist Women’s Health Center, FSU Archives, “Organizational records documenting the administration and research of the Feminist Women’s Health Center, Inc. and the Women’s Choice Clinic of Tallahassee, Florida.”