Between Betty and Me: Art, Activism, and Accessibility

by Susan Robinson, aka Susan Wood-Thompson

The Art Part

I met Betty Bird when I went to her Commission for the Blind office on the University of Texas campus in 1969. I wanted to inquire about getting work reading for a person who was blind. When Betty learned I had a master’s degree in English, she told me that she was tired of readers who couldn’t pronounce the words. She said that she would like to hire me to read her textbooks onto tape for her. I said yes.

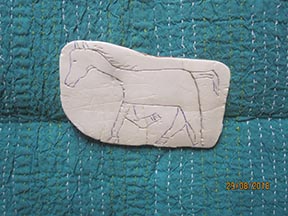

A few months later, we moved in together. One day, we were sitting at a picnic table near campus, eating sandwiches on styrofoam plates. When I learned she’d lost her sight at six, twenty-one years earlier, I asked if she had any visual memory. She said she thought she remembered the color blue, but there was no way to check it out. We had finished our sandwiches. I handed her my ballpoint pen, asking her to draw something from when she could see. Without hesitation, she drew a horse looking determined with mane flying and hooves trotting. She told me that after losing her independent mobility along with her vision, her brother had bought her a horse, Shorty, who soon learned to take her from the farm where she lived to the nearby village. She loved Shorty, and they visited the village most days until Betty’s family moved to town.

We named the horse she’d drawn “Jelly,” and we put him up on the wall of our home, and of every home we had together through the next twelve years. His creation was perhaps the most original thing I’ve ever been part of.

By 1987, Betty and I each had moved to New York City, New York; and each had a new partner. When the four of us were having dinner in a restaurant on her birthday, I showed Betty two stained-glass versions of Jelly. I had hired an artist to make them. There were only minor differences in the two, yet she could feel the difference, and I was pleased when she picked for herself the one that was also visually livelier. Neither captured the beautiful sense of speed the original Jelly had. But Betty loved and kept hers; and I kept and loved mine.

In 2014, I saw in The Paris Review an interview with poet Henri Cole, who had been my student when I was teaching at the College of William and Mary where Betty was getting her PhD, in Williamsburg, Virginia. Henri was often at our house, and he grew to be our good friend. (It turned out that since those days, he had become a prominent author of autobiographical poems, often using images of gay life. He had published a number of books of poetry.) In the interview, he mentioned that having grown up in a military household, he had never been in a home like Betty’s and mine, that we were liberators for him.

When The Paris Review interview came out, Henri and I renewed our correspondence, which led to my sending him the original Jelly. And that led to and his writing and publishing in his book, Blizzard, a poem about Betty and her horse, Shorty, called here “Jelly.” The poem was dedicated to Betty and me.

Betty died in November 2022. In her last year, she and I debated where she wanted the artwork of Jelly to stay for good. She said she wanted Jelly to go to a lesbian archive; and she wanted one of the stained-glass versions to go with it, along with Henri Cole’s poem. Here are photos of them all.

JELLY

by Henri Cole for Betty Bird and Susan Thompson

Rubbing the bristle brush across his backbone,

securing the bridle, riding his stretched-out body

on the dirt road to town (past the Texaco station),

and following his head through hair grass and cornflowers,

she was some kind of in-between creature,

browned from the sun. To the sightless,

at the State School for the Deaf and Blind,

knowledge came in small words—under, over,

next to, inside—but it was the clip-clop of Jelly’s

hooves, his fragrant mane and muscle memory

that carried her forward, hollering, Run, Jelly. Run!

Then, with one soft-firm Whoa, he did, though she

was only six, her child-hands gripping the reins tight,

hearts thumping a testimony to the love feeling.

The Activism Part

Jelly was the result of Betty and my first collaboration, and others followed, some of which were activist projects. In 1978, we and a bunch of other lesbians began meeting for a year to plan what would become the first “WomanWrites,” which came to be spelled Womonwrites. This was a gathering started by Southern lesbian writers. For a number of us, this endeavor was the answer to survival as a growing, Southern writing community, one that was distinct, shaped and colored by the southernness of our lives. Our survival was made urgent when Catherine Nicholson and Harriet Desmoines moved with their three-year-old literary and art journal, Sinister Wisdom, from North Carolina to Nebraska. Catherine and Harriet’s joint sensibility and creativity had fostered Southern lesbian writing with a power that none of us Womonwrites planners were willing to lose.

For a year, these planners met for planning weekends at Betty and my house in Columbia, South Carolina, which was approximately half way for those coming from Atlanta, Georgia, and for those coming from the North Carolina Triangle area. When that began, I noticed something I hadn’t expected: Betty, otherwise a lively, talkative person, was laid back when they were here. I put it together in my head. The rest of us had read, as soon as they hit our mailboxes, the latest issues of lesbian journals. Our conversations drew a lot on those readings. Betty, on the other hand, often hadn’t heard all these yet because she and I had to work around our work schedules for me to read them to her. And reading aloud takes longer.

Privately, I worried about how this affected Betty’s ability to talk in the group and to be included. When the first Womonwrites took place at the end of a year of planning meetings, it was held at a campsite outside Atlanta. There, one day as Vicki Gabriner and I were walking down a dirt road, I told her about my dismay at realizing Betty’s exclusion from the literary and political discussions that were so important in our community, and about my failure to find a solution.

I had considered the two sources for turning print material into audio that were available to people who were blind. Recordings for the Blind did that, but you had to send them two copies of each publication to be recorded: one for the person reading it onto tape, and one for the one listening to make sure there were no mistakes. At the time, the average annual income for a person living with blindness was only $2,000, making the costs of buying two copies of a publication, and buying the postage required to mail them, out of our reach. The other source was the Library of Congress. When I contacted them about what I wanted on audio, they said that the library didn’t believe blind women should be reading “that type of material” (which meant lesbian and feminist material), and they wouldn’t record that for us.

I told Vicki about all that, and that I had to find someone to put the lesbian journals on tape. Vicki said, “You have to do it yourself.” At first, I was discouraged by not knowing how to make that happen. It sank in for me that Vicki was right.

Once we got back home, I told Betty about all this. She and I set to work to make it happen. With the experience that I’d had with the Library of Congress in mind, we chose the cautious title for our project, “Feminist Taping for Handicapped Readers.” I applied and got us 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status. Betty ordered 100 cassette tapes for $1 apiece from an organization she knew. We arranged for women to read onto tape from each of the four journals that we wanted to include: Sinister Wisdom, Feminary, off our backs, and Conditions. We sent them the format that Recordings for the Blind used to make sure every recorded journal would as closely as possible replicate the experience of sighted readers when reading the print versions. For example, the page numbers were read at the end of the first sentence on each new page.

Betty and my next puzzle was to figure out how to duplicate the cassettes in a way that was affordable. That way, we could send them to as many women who wanted to read/hear them. We were taking a trip to New York City, and we stopped on the way to meet and visit with Kady van Deurs and Eileen Pagan. They lived in Monticello, New York. Kady was a carer for their friend Connie Panzarino, who lived with spinal muscular atrophy. Pagan had transcribed Connie’s words on tapes into print that would become Connie’s autobiographical book, The Me in the Mirror (1994).

When we told them what Betty and I were hoping to establish, Kady and Pagan suggested we meet in Manhattan (in New York City) to brainstorm. At Peaches lesbian bar, the four of us reviewed Betty and my progress. Kady and Pagan told us that they knew a gay man, Ramon, who worked in the tape duplication shop of the New York Lighthouse for the Blind. They contacted him the next day, and he was on board to duplicate for free our tapes, which he would do after his work hours. We sent him the original tapes through the U.S. Post Office’s program, Free Matter for the Blind, and Ramon sent us the duplicated copies, also through Free Matter for the Blind.

Meanwhile, Betty and I had advertised our project, Feminist Taping for Handicapped Readers, in the journals to be taped, as well as to other lesbian publications. We also advertised through facilities that served people who were blind or print-handicapped (unable to hold books or turn pages). Sixteen U.S. and Canadian women answered our ads. For the next two years, I put Sinister Wisdom on tape. Other women recorded the other three journals. Betty spot-checked each tape to be sure it complied with the guidelines of Recordings for the Blind. We mailed the tapes to the sixteen women.

At the end of the two years, Betty told me she was burning out. We notified the sixteen women that our service would end. Shortly, we got a call from Marj Schneider in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She, her friend Kathy Hagan, and lesbians they knew had relied on our tapes. Marj wanted to know if she and Kathy could come to Washington, DC, where Betty and I now lived, to learn from us everything to carry on the work. Marj and Kathy came for a weekend, and Betty and I told them every part of the process we used. We learned from them that more lesbians than we’d known benefited from our tapes because once the sixteen women finished reading, they passed along their tapes to friends, who when they finished, passed them along to others again.

Marj and Kathy returned home, bought a duplicator, found women to read the journals onto a tape, and found volunteers for related jobs for the four established journals and more, including many books by lesbians. They did this for ten years under the name, Womyn’s Braille Press. Then Marj, the central worker, burned out. They donated the many tapes they had made to a gay archive in the Midwest.

Years after Betty and I had given our taping venture to Womyn’s Braille Press, I was traveling in Canada. At a flea market, I was delighted to see something I hadn’t known about before. It was a white sweatshirt with the words, “Womyn’s Braille Press,” written in raised-print black letters and also in Braille.

Do you have something you’d like to add to this tribute?

Take the leap and share the lesbian love.

Or you could write a few lines in tribute to another lesbian.

Just contact SLFA.