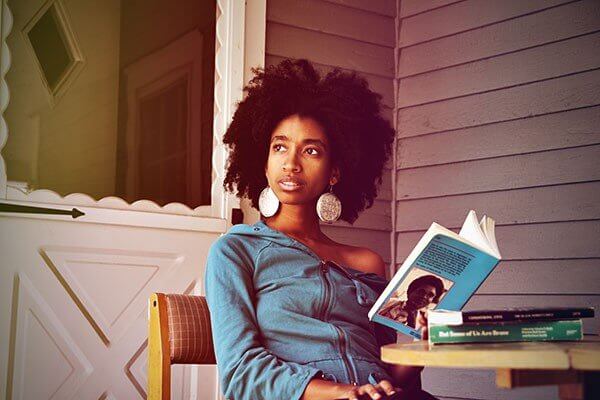

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: Black Feminist Love Evangelist

Interview by Rose Norman in Atlanta, Georgia, June 7, 2019

Alexis Pauline Gumbs is too young to have been part of the second and third wave activism that this project documents. She is, however, a beneficiary of some of it. She is engaged in her own herstory project: the Mobile Homecoming Trust Living Library and Archive, similar to the Southern Lesbian Feminist Activist project, and focused on Black or African American women. This interview ranges into several related projects, including her Black Feminist Bookmobile project.

Personal Background

When Alexis was very young, the spark for writing ignited within her when she wrote a praise poem for her father. As a teenager, Alexis participated in a Youth Communications summer program, and published pieces in Vox, their teen newspaper. The program incorporated a writing contest for teenagers through Charis Circle and More. This led to her weekly participation in the Young Writers Group at Charis Books and More and a life-long love affair with books and Charis.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs has edited one collection, Revolutionary Mothering, with Mai’a Williams and China Martens. She has written three books that are her Black feminist triptych: Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity (inspired by Hortense Spillers, 2016), M Archive: After the End of the World (inspired by M. Jacqui Alexander, 2018), and Dub: Finding Ceremony (inspired by Sylvia Wynter, 2020). Her fourth book Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, won the 2022 Whiting Award in Nonfiction. The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde: Biography as Ceremony, Gumb’s fifth book, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Writing is only one aspect of her brilliance. Alexis has been recognized by the Advocate’s 40 under 40 list, the UTNE Reader’s 50 Visionaries Transforming the World list, the Bitch 50, Colorlines LGBTQ Leaders Transforming the South list, the Too Sexy For 501-C3 award, and more for her work with the Mobile Homecoming Project. She is a Lucille Clifton Honoree, Firefly Ridge Honoree, and Pushcart Prize Nominee.

Biographical Note

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, born in 1982 in New Jersey, moved with her family to south Florida. At age 14, they moved to Atlanta, where Alexis attended high school and subsequently joined Charis Books & More’s Young Women’s Writing Group. During that time, Alexis wrote for Vox Teen Communications. She attended Barnard College at Columbia University, later earning her PhD in English, African and African-American studies, and women and gender studies at Duke University (2010) in Durham, North Carolina.

Alexis’s poetry was included in Best American Experimental Writing in 2015. Along with her partner, Sangodare, she cofounded the Black Feminist Film School to produce films with a Black feminist ethic.

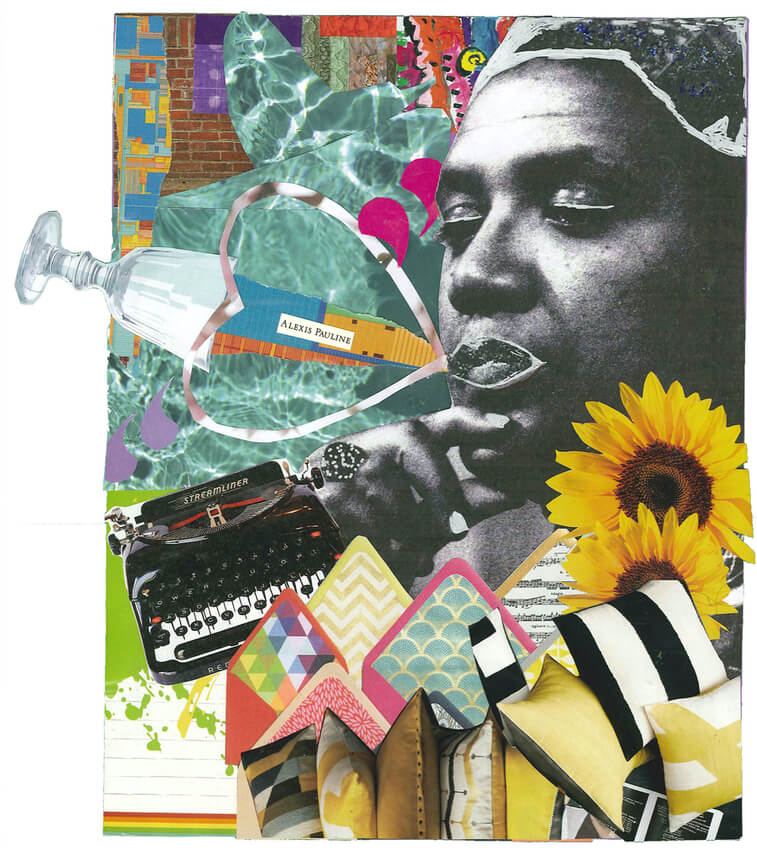

Alexis is also a visual mixed-media artist. Her current series of Black Feminist Breathing Collages are available for purchase.

Interview

Alexis was given a list of questions that she answered, often without prompt, throughout the interview.

Rose Norman: Talk about becoming a Black feminist. Was it due to particular books? People?

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: Really, it’s because of Audre Lorde. I got the collected poems of Audre Lorde from Charis Books & More, and that was my book. Every assignment I had in high school used a quote from either Audre Lorde or James Baldwin. I got his works at Charis, too.

At home, my mom had Angela Davis’s books and Alice Walker’s books. She gave me Ntozake Shange’s books. She [her mom] took one of the first courses ever taught on Black women’s literature. Professor Dr. Margaret Wade at SUNY New Paltz taught a course called The Black Woman in 1976. I was immersed in that context, but it was Audre Lorde’s self-identification and her definition of Black feminism that I strongly identified with. This was what I believed, the type of world I wanted to create.

RN: Was Lorde offering possibilities not available to you?

APG: I don’t think so. I think it was really the clarity Lorde offered. My family offered me huge vistas of possibility. Even before I was born, my Mom told me she would look down at her pregnant belly and say, “You are going to transform the world!” She had worked for Essence Magazine and left that job when she decided to stay home with me, her first child. When people questioned that decision, she would say, “I’m creating a future leader of the world!” She was super clear about that and was telling me that when all I could receive was the vibration.

RN: Your books Spill and M Archive are influenced by Black feminist scholars. Were these people you knew personally, or was it a literary friendship?

APG: It’s different with different ones. Spill is dedicated to Hortense Spillers’ work. I learned about her through reading her work, which was introduced to me by Black feminist scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin. Dr. Griffin teaches at Columbia and was my professor [Dr. Griffin is currently William B. Ransford Professor of English and Comparative Literature and African-American Studies at Columbia]. I gravitated toward Farah Griffin because I knew I was a Black feminist. Hortense Spillers is someone I have since met and do have a relationship with.

I met M. Jacqui Alexander in Atlanta when Dr. Alexander was a visiting chair at Spelman. She mentored me while I was doing dissertation research at Emory; she has been an incredible mentor to me. Jacqui Alexander has her own relationship with Charis, though I didn’t know that in high school. She has been a huge gift in my life.

The third book in the triptych is inspired by the Jamaican scholar Sylvia Wynter, whom I have not met, but who has been super instrumental in ethnic studies at Stanford. I would love to meet her; her writing has impacted me in ways I cannot even innumerate. [Sylvia Wynter was chairperson of African and Afro-American Studies, and professor of Spanish in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Stanford.]

Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind (2007)

APG: While I was in graduate school at Duke, I created The Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind , which I think of as a tiny, Black, feminist university. We conducted intergenerational educational programs in my living room. We had the School of Our Lorde, which was based on my archival research at Spelman on Audre Lorde’s papers. We also had Juneteenth Freedom Academy, which was based on my research on June Jordan at Harvard, and the Lucille Clifton ShapeShifter Survival School, based on my research at Emory.

I love bringing my research on Black feminist writers into forms that are accessible to people of multiple age, to whole families with babies, and the grandparents of those babies. Everybody should be able to engage it together.

Black Feminist Bookmobile

APG: The bookmobile project came out of the Eternal Summer project. We had established a lending library as part of the Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind. We got so many incredible book donations from Black feminists who wanted to give us books from their library, or those they had passed on to their children who then donated them. Some were moving home to take care of their mother and they wanted to donate part of their collection, or they were being displaced and wanted to make sure that their amazing collections of books were safe. We have this incredible library and want to make sure parts of it are visible and shareable. Some books are more for reference but can circulate within the community. [Alexis refers to the bookmobile as “a tiny, Black feminist nerd utopia.”]

RN: How are you storing these? It sounds like a lot of books!

APG: It is a lot of books. They’re stored in beautiful bins that say “Black Feminist Bookmobile” on them. We create installations with them in different places. We just did one at a Humanities for the Public Good gathering in Chapel Hill. We’ve done different reading rooms for people’s birthdays. In July, on June Jordan’s birthday, we set up at a favorite gazebo in a public park in Durham, North Carolina, and it became the June Jordan Reading Room. People come out and look at her books and at books made possible by her work, or that are in conversation with her work.

RN: Do you lend out the books?

APG: We lend out some of the books, books we have multiple copies of. The books that are rarer (books that we want to preserve) can be read and worked with on site.

RN: Do you have an actual vehicle for driving the books around?

APG: We’ve been doing pop-ups under the name Bookmobile for a year and a half now (we had our first event December 2017), but we’ve done pop-ups with the lending library since we started the Eternal Summer project in 2007.

All of it evolves. When we were doing that Eternal Summer programming in my living room, the bookshelves in my living room became the lending library, and then it became more than that. We started circulating books; that’s why we created the Bookmobile. My partner [Sangodare] and I have also been doing the Mobile Homecoming project, which is also an experiential archive project.

Mobile Homecoming Project

The Mobile Homecoming Project started as an interview project, and then moved to retreats. We did ten different retreats over the last ten years. Now we’re moving to the phase where we’re getting ready to buy some land and create the Mobile Homecoming Living Library, which is a gathering space where we get to be an experiential archive together. Ultimately, it will be an intergenerational, interdependent, and assisted living space, both a living library and a space of care and listening.

Gail Reeder (who was present in the room): Listening to this makes me think what a blessing this project is for people who are downsizing and can’t bear to discard their collections.

APG: Yes, they’re [the books] really priceless. When we were doing a residency in Minnesota, we learned about a movement library in St. Paul, Minnesota. A labor historian made an old Carnegie library into a movement library. The way they organize their collection is similar to the way we organize ours, which is by donor, not by author or subject. The collection of Akasha Gloria Hull is an example. The collection itself is an intellectual work. It’s interesting to find bookmarks and concert tickets that you might find stuck in books.

Mobile Homecoming exists as an intergenerational and experiential archive project

to amplify generations of Black LGBTQ brilliance.

Mobile Homecoming Trust Living Library and Archive

As Alexis said, “All of it evolves.” Currently, The Black Feminist Bookmobile and The Mobile Homecoming Project projects have evolved into an inspired union as the Mobile Homecoming Trust Living Library and Archive. The project began with a cross-country journey in a retro RV to find Black elders and to create an intergenerational community of love and support across the United States. Their homecoming brought them to Helena Cragg and Sylvia Williams at the Soul Sanctuary stewarding land in Durham, North Carolina. Mobile Homecoming exists as an intergenerational and experiential archive project to amplify generations of Black LGBTQ brilliance.

University of Minnesota, Winton Chair in the Liberal Arts

[Alexis is the first Black woman ever to hold this endowed chair. She held it for two academic years, 2017-18 and 2018-19. The position has not traditionally involved community interaction apart from public lectures.]

APG: The Twin Cities of Minnesota are an incredible place, especially for Black feminist theatre producers. Part of my project there was due to Laurie Carlos, who passed away in 2016. She did incredible mentorship of young theatre makers in that area. Generations of theatre makers have benefited from her. At the University of Minnesota, I worked with the Mama Mosaic theatre company, under one of the founders, Signe Hardily, a Black lesbian feminist and incredible theatre director and facilitator, creating interactive, community-based theatre based on my books Spill and (especially) M Archive. Actually, we worked with a whole bunch of performance and theatre artists. It was such an honor, an amazing way to learn about performance, and just to learn what you learn when people reflect back your work to you from their own genius.

Signe and Erin Sharkey worked as producers (Signe also as director) of performances, where they generated performance works based on the books, not performances of the books. The choreographer, Leslie Parker, has done a new dance work based on Spill, going up in July [2019]. [Erin Sharkey is also cofounder of the local art project “Free Black Dirt.]

These [performance works] were especially appealing to me because it’s what I am about: how these things that are in books and archives can be made accessible to people who actually experience them. I feel really blessed to be part of a community of Black feminist activists and theatre makers, and to see those two things intertwined.

Zenzele Isoke was chair of the Winton committee at the University of Minnesota at the time I was chosen, and is the person who invited my partner and me to come. She had the vision of using these resources in a way that was collaborative, and feminist, and involved the community. The position is defined for innovative people with boundary-breaking ideas. I feel like we approached it in a way that was more collective because of our feminist values. Penny Winton created this endowment. She is an elder who went to the University of Minnesota and wanted to create something that would allow innovative thinkers to transform the university community.

Question: Yet you are the first person in that position to come there and do anything but write a book?

APG: Well, I think they gave a public lecture! No shade to the former Winton chairs! They are really amazing. We just took a much more collective approach.

GR: Minnesota is a very white state. They’ve gotten a lot of refugees, though, and that has given them more diversity.

APG: That’s true. There’s a community of folks in the Rondo area who either freed themselves [from slavery] or, upon Emancipation, moved to Minnesota and founded the community called Rondo. The grandparents of Leslie Parker, the choreographer who’s doing a dance piece based on Spill, were part of that wave of migration. There’s a whiteness of the state that covers over pockets of diversity.

Coming Out

“… Black feminism: it’s a love-based ethic. It means that love transforms us. Nothing, certainly not patriarchy and not heternormativity or structure, comes before what love is. We get to be present to love.”

RN: You haven’t mentioned anything about coming out as a lesbian during all this immersion in feminist literature.

Katina Parker interviewed me and my mom for a project called Truth. Be. Told. When she asked my mom about me coming out, my Mom said to me, “Were you ever in??” (laughter)

I was a late-bloomer. I was already a Black feminist. I already had my conceptual queer politics before I was ever in any kind of dating situation. I was really clear in my politics, a super-outspoken queer ally and participant in [Gay] Pride in high school, but for myself, personally, it was a mysterious, indeterminate thing. I had graduated from college before I dated a woman. When I first talked to my family about the first woman I was dating, they were not surprised.

I definitely knew that I was not conforming to the idea that you reproduce the status quo

through your interpersonal relationships. In fact, the opposite,

we destroy the status quo through the power of our love and our relationships.

They saw it as consistent with a love ethic that I had spoken about, that I think of as part of a Black feminist ethic. In the way that I live Black feminism, it’s a love-based ethic. It means that love transforms us. Nothing, certainly not patriarchy, and not heternormativity or structure, comes before what love is. We get to be present to love. I didn’t necessarily know that the love of my life would be a woman (those are things that are a mystery), but I definitely knew that I was not about to be conforming to the idea that you reproduce the status quo through your interpersonal relationships. In fact, the opposite, we destroy the status quo through the power of our love and our relationships.

NOTE: These interview notes have been edited by the interviewer and the interviewee. Extraneous material and repetitions have been removed, and in some cases, material has been rearranged for coherence. The interviewee has been encouraged to change or add anything attributed to or about her in these edited notes, including completely rewriting the interview as a personal memoir.

These edited notes will go to the archives at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubinstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University, in Durham, North Carolina, along with the unedited audio interview.

See also:

Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s conversation with Hortense Spillers on Left of Black

Biographical information, works, projects, and inspirations of Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Communiqué to White Ally Heaven, Sinister Wisdom 87 (Tribute to Adrienne Rich – Fall 2012): 86-100.

Dub: Finding Ceremony, Duke University Press, 2020.

Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind

Evidence, a contribution to Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, AK Press, 2015.

An introduction to M Archive: After the End of the World, Duke University Press.

Excerpts from the echolocation lecture by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, author of M Archive: After the End of the World, Evergreen Art Lecture Series, 2017.

Exhale. Collage by Alexis Pauline Gumbs for Toni Cade Bambara based on a photograph by Susan Ross.

Honeypot (contributor), Duke University Press, 2019.

M Archive: After the End of the World, Duke University Press, 2018.

Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines, PM Press, 2016.

Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity, Duke University Press, 2016.

Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, AK Press, 2020.

Video: “A Homemade Field of Love,” The Poetry Project, 2021.

The concept behind Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s current project, “Visionary Daughtering”

who breathes with me, BrokenBeautiful Press.

Without Apology: Poems in Honor of Black Women by Clyde E. Gumbs, Blurb, 2016.