Beth Marschak: Lesbian Activist for Civil Rights and Human Rights

Notes from phone interview by Rose Norman, November 18, 2015

My feminism began in college. I started a women’s lib group, organized the first Earth Day in Richmond, and got in jail for antiwar and civil rights actions.

Beth Marschak: I was born in Pennsylvania, and I grew up in a working-class family here in Richmond, Virginia. My parents were Southern Baptist, conservative Republicans. Of course, I gradually parted with them on many things although we always stayed on good terms.

I considered myself to be a feminist by the time that I was in college. As I was growing up, I often ran into things that girls were not allowed to do, things that I wanted to do. In high school, I wanted to take shop class*, and girls weren’t allowed to take shop. My option instead of shop was home economics**, which wasn’t really interesting to me. My parents actually backed me up on that. The school would not budge. They would not let me take shop class. The school finally decided to let me take two semesters of art instead of taking home economics. That was a slight victory for me with that. Another time, I wanted to enter a contest that General Motors had about models of cars, and they wouldn’t accept my entry [because I was a girl].

*[In junior high school and high school,shop class was a hands-on, vocational class, teaching how to use tools in the industrial crafts such as carpentry, mechanics, metalworking, welding, etc., a class for boys.]

**[Home economics class consisted mainly of learning basic cooking and sewing skills, a class for girls.]

Biographical note

Beth Marschak grew up in a working-class home in Richmond. She actively engaged in the social-change movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, such as: the American Civil Rights movement, the women’s liberation movement, the ecology/ environmental movement, the peace movement, lesbian rights, and gay liberation. She came out as a lesbian in the early 1970s, openly identifying as a lesbian in her civil rights and human rights activism.

When exploring colleges to attend, I thought first of the University of Virginia. However, at that time, they were not admitting women students. A number of things like that in my life led me in the direction of being open to feminism. By the time I found out what feminism was, I definitely considered myself to be a feminist.

My feminism began in college. I went to Westhampton College, University of Richmond. Although Westhampton was pretty much a women’s college, we sometimes took classes on the men’s side of the campus. I helped to start a women’s liberation group there called the Organization for Women’s Liberation, OWL.

I was not only interested in women’s liberation. I was interested in everything. In college, I became very active in a number of different social and political movements of that time. As part of the ecology movement, I helped to plan and organize the first Earth Day in Richmond in 1971, held in Monroe Park. As part of the antiwar and the civil rights movements, I was arrested and went to jail several times in various actions involving the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

BM: In 1973, after college, organizing was happening around lesbian and gay issues in Richmond. I was in an early group called GAP, Gay Awareness in Perspective. It started off with about half women… but it gradually lost women because the men really had a much narrower concept of what they wanted. Although certainly, some men had a feminist consciousness, many of them were completely sexist. That group didn’t continue to interest me very much. Around the same time that I was dropping out of that group, we started up Richmond Lesbian Feminists [in 1975].

I had been involved early on with the National Women’s Political Caucus, which had an organizational meeting here [in Richmond] in 1971, and I went to it. I had connected with another woman from Westhampton, her name was also Beth, and we decided that we should start something at Westhampton. That’s what led me to help start OWL [Organization for Women’s Liberation]. I remained active in the National Women’s Political Caucus for a long time. I was very much involved with the Richmond Area chapter, which was called the Third District Women’s Political Caucus.

I was active in the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus, serving on their steering committee for a number of years. In 1974 or ‘75, I was elected to the national steering committee of the National Women’s Political Caucus, as the Lesbian Caucus representative. I continued on that steering committee serving in different roles. I was the Lesbian Caucus representative for about six years, then a Virginia representative for a while. Then, I chaired the Site Selection Committee for four years. My last two years, I chaired the Judicial Committee, which settled internal disputes. So, I was in the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus of the National Women’s Political Caucus for about sixteen years.

BM: Before Richmond Lesbian Feminists was started [in 1975], many lesbians were active in another women’s organizing group, the Richmond Women’s Center. We would often meet at the Woody Guthrie Community Center, near the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University. I was also involved with the Woody Guthrie Community Center, a sort of leftist-based group that had a lot of different kinds of progressive programs. We had a food co-op, a child care co-op, and we showed films that could not be found in regular movie theaters, usually political films.

There were quite a few lesbians in the audience. They were so delighted with Home Movie

that I offered to show it again right then. I did. I rewound the tape and showed the film again.

I showed the first lesbian film there. I think it was the first time a lesbian film was shown in Richmond. It’s called Home Movie [1972], a very short film by Jan Oxenberg. I had gotten it through a film collective. I remember that we showed it along with Salt of the Earth, a leftist film with a feminist slant. There were quite a few lesbians in the audience. They were so delighted with Home Movie that I offered to show it again right then. I did. I rewound the tape and showed the film again.

The Richmond Women’s Center eventually had space at the YWCA. The largest project that we did was called the Women Helping Women Hotline [telephone help line]. We were one of the early groups in Richmond to work with sexual assault and domestic violence calls. Eventually, NOW did more – and more in-depth projects – with that. That hotline became a major program of the Richmond YWCA.

We had a falling out with the YWCA because our newsletter had openly lesbian content in it. We were kicked out. We went public with that, and got newspaper coverage [of the discrimination]. The Women’s Center continued for a little while after that, but it wasn’t really possible to do much without a place to work, which we had lost. There wasn’t a good way to keep a dedicated telephone line and things like that. Again, that was happening around the time that we started Richmond Lesbian Feminists.

BM: Stephanie Myers was very interested in starting a lesbian group. She and I were lovers at the time. I was interested in starting a Lesbian Caucus within the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus. I was in the National Women’s Political Caucus, and it had a Lesbian Caucus there. I thought it would be helpful for lesbians in the organization to have a way to work together, talk, and figure out things that we might want to do.

When the annual conference was organized in 1974, we included a lesbian workshop. That workshop recommended that the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus sign on to the Ms. Magazine petition for sanity, which was about lesbian rights. We decided to start a group. The Virginia Women’s Political Caucus did endorse that petition for sanity.

There was a very strong interest in having a lesbian group. For most people in the group, there was a strong desire for it to be also a feminist group. I could see that my idea of having a lesbian caucus of the Virginia WPC was not going to happen.

The people who came to that Virginia Women’s Political Caucus meeting, in many cases, came just for the workshop on organizing lesbian caucuses. It was publicized not just by the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus, but also by the Richmond Women’s Center. Some women who might not normally have come to a Women’s Political Caucus event, but would come to a lesbian caucus event, found out about it.

There was a very strong interest in having a lesbian group. For most people in the group, there was a strong desire for it to be also a feminist group. I could see that my idea of having a lesbian caucus of the Virginia WPC was not going to happen. I have never been one to go down a path that didn’t make sense. At that point, we were talking about a statewide, lesbian-feminist group. I could see that we were open for social, political, and cultural involvement. I was interested in that as well, and I turned my attention to that.

At that workshop, we set up a future meeting. When we had the follow-up meeting, people decided to have a state organization, Virginia Lesbian Feminists. Three localities had enough people to have local chapters: Richmond, Charlottesville, and the Tidewater area.

Within a year, it was obvious that we didn’t really have a way to make a state organization work. The Tidewater one did not last long at all. The Richmond and Charlottesville groups continued to do things in their area, but the state group [Virginia Lesbian Feminists] dissolved. The Charlottesville group continued into the 1980s. The Richmond Lesbian Feminists is still active today. This is their 40th anniversary year [in 2015].

BM: In my experience with various LGBT groups in that area, they have not often lasted very long. An exception was Our Own Community Press, which was there for a long time, out of the Unitarian Universalist Church. That was probably the only LGBT newspaper that tried to cover things happening all over the state.

I think one of the reasons that lesbian groups failed is that they had a large and active bar culture. Not that there weren’t bars in Richmond, but they weren’t on the same scale. Maybe there wasn’t as much interest in having other social things going on. The military has a big impact on that area. Norfolk has a huge naval base. Some people weren’t comfortable being active in a group with a [progressive] name. Also, people were moving in and out all the time because of the military. Probably a variety of factors worked against it.

They did have a lesbian rock group, Mermaids in the Basement, for many years. They played in Richmond, at festivals, even later on at places like In Touch and CampOut. They had their base by playing in the bars down there. That allowed them to last a long time.

BM: In 1974, the Richmond Women’s Center, the Third District Women’s Political Caucus, NOW, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Sisters in Prison, and (I think) the Women of Socialist Worker’s Party (a Marxist group – I can’t recall the exact name) all came together and planned the first women’s festival in Richmond.

This first women’s festival was held in Monroe Park [July 13, 1974]. We had some big-name speakers in the women’s movement: Margaret Sloan worked for Ms. Magazine and had family in Richmond; and she is African American. Florynce (Flo) Kennedy was a well-known activist and feminist, is also African American. They were both involved in the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). Bessida White, one of the women activists here in Richmond, was a vital link. Bessida was also in the National Black Feminist Organization, and she had contact with lots of people. Then we had novelist Rita Mae Brown, who was just becoming famous. Kay Gardner, the wonderful flute player, was there. It was outdoors. There were information tables that included lesbian materials. It was really the first time there was something public [in Richmond] that had an overt lesbian theme to it. That was before Richmond Lesbian Feminists started.

There were three of those women’s festivals. The other two were held in Byrd Park. Those were a little bit more private; therefore, they tended to be only women attending [in 1975 and 1976]. The Richmond Lesbian Feminists organization was involved with those two festivals.

BM: They were the only ones who were openly lesbian there. Margaret Sloan is a lesbian, but she was not out then. Of course, her friends and colleagues knew. And of course, many women who were openly lesbian were involved with planning and coordinating it.

BM: The Richmond Women’s Center and the Third District Women’s Political Caucus were the major organizers of the first women’s festival in Richmond, and there was a lot of cross-membership in those groups. As I mentioned, when the YWCA kicked out the Women’s Center in 1975, we went public with that. We put it in the Richmond newspapers. I think the YWCA was trying to be very quiet about the whole thing.

When we were trying to get backup, and trying to raise some money, we held a fundraiser with Mari Hasegawa as speaker. She was with the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), and she was a very strong supporter of lesbian rights. Mari was at one time president of the national branch of WILPF; and she was one of those who went to Vietnam during the Vietnam War. She had grown up in one of the Japanese internment camps. She was approximately my mother’s age. Mari’s daughter, Maya Hasegawa, was also a delegate to the International Women’s Year gathering [in Houston, Texas, in 1977]. I’m still in touch with her daughter, who is a feminist but not a lesbian.

One of the things that is important to realize is that the Richmond Women’s Center had mostly younger women, women in their 20s, and maybe a few in their 30s. The Women’s Political Caucus had a wider range of women’s ages. Quite a few of them were in my mother’s age group. The same was true of WILPF, and NOW was somewhat that way. There were some younger women in NOW, like Zelda Nordlinger, who was one of the main NOW organizers in the early days. She was in my mother’s age group.

Richmond Lesbian Feminists, from the earliest days, had Black women who participated although not at the level that they were represented in the population. But we did always have Black women participating.

Another difference was that while the Richmond Women’s Center and the Women’s Political Caucus didn’t have a lot of Black women participating, NOW and WILPF had minimal to none. Richmond is a majority Black city, and neither group had even 50% participation by Black women. The Richmond Women’s Center and the Women’s Political Caucus probably had between 10% and 20% Black participation.

The city was more than 60% Black at that time. The Richmond Women’s Center and the Third District Women’s Political Caucus were very interested in getting Black women to be involved. We tried a lot of ways to get that to happen. Richmond Lesbian Feminists, from the earliest days, had Black women who participated although not at the level that they were represented in the population. But we did always have Black women participating. A little bit later in the 1970s, our Richmond Lesbian Feminists were part of a Southern, lesbian, antiracism group that would meet in different parts of the South. I don’t remember if we had a name for that antiracism group. It was very informal.

BM: I think there are a lot of complex reasons for this, not just one reason. For instance, more of the people involved with the Richmond Women’s Center came from working-class backgrounds. More of the women in the Women’s Political Caucus came from middle-class backgrounds. That was a difference that would affect the rich, Black women that they were trying to reach.

We don’t talk much about class any more. I think class was definitely one of the things that had something to do with the approaches that different groups took, and the kinds of activities they would do. Black women who had a very strong, feminist identification, and who might be in groups like the National Black Feminist Organization, also wanted to be in other feminist organizations. They were perhaps more willing to put up with things that other Black women might not put up with.

Certainly, there was a lot of homophobia and heterosexism floating around. There was racism, not necessarily intentional racism; but people had come out of a racist culture. Just as I said about Gay Awareness in Perspective, they probably didn’t think of themselves as that way. I’m sure that for Black women and women of color participating in majority white organizations, they would be dealing with that. It would be a matter of what level of involvement they were willing to have. I think it’s more than just wanting to have their own groups although I do think that people often wanted to have their own groups.

BM: Several women here were part of the National Black Feminist Organization (NFBO) in the 1970s. They did have a local group here for a while, but it didn’t last very long. I am not aware of any formal Black lesbian organizations local to the Richmond area in the 1970s or ‘80s. But there were informal groups I knew of, such as the softball teams. I remember going with several women from the NFBO to New York City to a national program put on by the NFBO and by Sagaris [which means double-headed axe, similar to the labrys]. Sagaris was a feminist, summer institute in 1976 in Vermont. They had feminist and lesbian-feminist instructors, including Rita Mae Brown and Charlotte Bunch.*

Some of the women in that NBFO local chapter were not very comfortable with lesbians or lesbian issues, and some were. Bessida White was very comfortable, and she was involved in leadership in both white and Black organizations. We had an exciting trip. We got to see Ntozake Shange’s choreopoem show, “for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf” when it was first performed off Broadway. I think now there was a local group that was part of the National Black Feminist Organization, and it was active for several years. I believe that was also in the same time frame as the second, two women’s festivals, and that the NBFO were sponsors of them as well.

[*Beth Marschak provides this link to a bibliographic record about an archived recording made at Sagaris: https://www.pacificaradioarchives.org/recording/iz1361]

BM: The Lesbian Womyn of Color (LWC) group, started in the 1990s by Terrie Pendleton, began with a classified ad in Style Weekly, a local general arts and events publication. The group also ran ads in the Richmond Lesbian Feminists Flyer. The LWC group was very successful at first. I went to a couple of their house party events that drew over a hundred people. They had a number of other events as well. You’ll have to get the full story from Terrie. They had various differences of opinion, and it became difficult to keep the group together.

The group that followed the Lesbian Women of Color were the Gatekeepers that had the support of a Black LGBT club here in Richmond, called Club Colours (which is still here). They had a newsletter, and they were active for a couple of years. Those are the only two, Black, lesbian groups that I know of that have been here.

The Black lesbian community has always had more informal levels of organization. While there was an organization with a newsletter publicizing events, there were many other things that Black lesbians were organizing. They were active in the women’s softball league. I saw many teams of Black lesbians playing softball. Also, I know from informal discussions that there were house parties, card clubs, and other kinds of organizing although not in the traditional way we think of organizations in the dominant culture.

The first time that I saw a large number of African American lesbians in Richmond was when I went to a Joan Armatrading concert. This was in Richmond at the Empire Theatre, an old theatre building being renovated. One of the things they did to raise the money to revive the space was a concert. I had never seen so many Black women in couples before. There were clearly a lot of them. This would have been in the early 1980s. The women weren’t necessarily holding hands, but they were clearly couples.

BM: Richmond Lesbian Feminists had a newsletter from the beginning, starting with a one-page flyer that grew into a larger newsletter.

That was back before computers. We would meet together to talk about what we wanted in the newsletter. Individual women would go home and type the stories. After that, we would meet to cut and paste the typed stories together. And then, we had to get it copied. The process of putting together the newsletter was a major activity for a good while.

When Bev Rainey started editing The Richmond Lesbian Feminists Flyer in the late 1980s, she was editor of The Richmond Pride, which had become independent of the Virginia Gay Alliance. By that time, things were done on a computer. She worked on a Mac [personal computer with Apple operating system]. Most of us who had access to computers had PCs [personal computer with IBM-type operating system], and we’d type things to save them on a PC disk. I was the one responsible for transferring things from the PC disks to a Mac floppy disk so that she could use that to put together the newsletter.

Our Own Community Press was active for at least twenty years. There were various places where you could distribute things like that, for example, at some bookstores, some coffeehouses, and lots of the bars. It tried to include things happening all over the state. They used an office at a Unitarian Universalist church down in Norfolk. It was a wonderful newsletter for a long time.

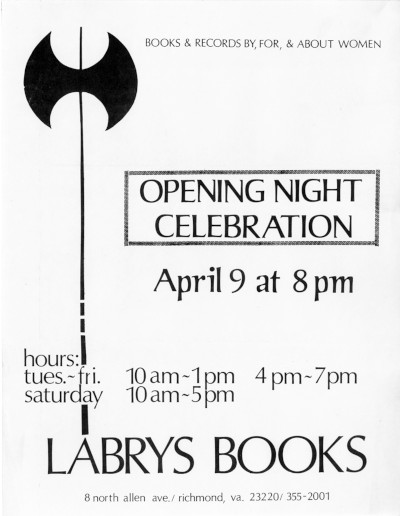

BM: Labrys Books was started by two women, Terri Barry and Joan Mayfield, who were partners, and who lived in the same house. That was in Richmond’s Fan district, which is close to Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), in that part of Richmond.

They had converted their living room into a bookstore. They had books and albums of music, and various other things. Many women in the Richmond community were involved in that in some way. People would come there and volunteer. It was sometimes used as a meeting space, too. Terri and Joan were originally students at VCU. When they left, they moved to the Washington, DC, area.

When Labrys Books closed, people felt a real lack from not having a women’s bookstore. Fairly soon after that happened, WomensBooks was organized. It was organized as a co-op, and I was one of the organizers of that. They originally used space in the YWCA. By that time the YWCA had changed their mind – they were no longer trying to keep lesbians out. The YWCA had had several leadership and board changes between when the Women’s Center was there and when WomensBooks was there.

After what had happened with the Women’s Center, I decided we needed somebody on the YWCA board. As it turned out, I was the person who I served on that board for eight years in the 1980s. Through their national conventions, I was in touch with women all over the country. I worked on getting the organization to take positions around lesbian issues and non-discrimination.

Near the end of my time with the YWCA, I was talking with Bobbi Weinstock. I showed Bobbi a brochure with a non-discrimination statement in it, and she said, “It took three years for those three sentences.” Also, when I was on the YWCA board, I was active in getting them to support disinvestment in South Africa. The local YWCA took a very positive position on lesbian custody rights as well as other discrimination in jobs and so forth.

WomensBooks outgrew the space at the YWCA, which was downtown, and it moved to the basement of the Fare Share Food Co-op, which was located on Main Street near Virginia Commonwealth University. Since they were a food co-op, and we were a co-op as the bookstore, we had some things in common. We also had personal connections. The manager of Fare Share Food Co-op was my sister Cheryl Marschak. She had also been active with the Richmond Women’s Center and the Women’s Political Caucus. She is not a lesbian; but I can’t leave my sister out of the story because she was an important part of how that worked.

We had been gradually declining, not just because of Phoenix Rising, but

because more mainstream bookstores were carrying feminist books now.

BM: What happened was that when Phoenix Rising bookstore opened, we would all go there. They had lesbian books. A year or maybe two after they had opened, our WomensBooks co-op thought it didn’t make sense to operate as a cooperative when people could now get books and other things from Phoenix Rising.

We had been gradually declining, not just because of Phoenix Rising, but because more mainstream bookstores were carrying feminist books now. We did a lot of our sales not at the Fare Share location, but rather by going to conferences and festivals. Those were also reducing a little bit. So there weren’t as many events for us attend where we could sell things.

Maybe people were getting tired, I think. There’s always a burnout factor in that kind of endeavor. We at WomensBooks felt it didn’t make sense to cling on until we would gradually go out of business. It made more sense to consciously close WomensBooks. We negotiated with Phoenix Rising, and they bought a lot of our stock. We put that money into an account to be used for women’s cultural events. Eventually, the money went into the Richmond Lesbian Feminists’ account for concerts and such.

Women’s Music and Women’s Festivals

BM: In the 1970s here in Richmond, there were a number of women who helped to organize and to promote women’s music. There were concerts with lesbian musicians Meg Christian and Cris Williamson, as well as local gay and lesbian musicians. Two of the Richmond musicians performed as Jan and Ann. They reunited and performed at our Richmond Lesbian Feminists’ 40th birthday party. [Several videos of their performance are on the Richmond Lesbian Feminists Facebook page.]

There was a women’s coffeehouse that met in different places at different times, including at several churches. Local women musicians would play at those. The concerts then were organized by lesbians. I’m thinking that Luna Music was one of those groups of two or three women who promoted or sponsored concerts. (I’ll get back in touch if I find further information about that.) There have been women here organizing concerts and music over the years. Certainly, in the 1980s, Richmond Lesbian Feminists women’s festivals included music in their festivals. They weren’t just music festivals because there were workshops, swimming, boating, softball, arm wrestling competitions, and lots of different things at those women’s festivals, in addition to music.

The women’s festivals were important from early on. It was such a great way to get together to have

experience and promote growth in lesbian culture. It was one of the ways that people connected.

In the 1990s, I organized a number of lesbian music events with Wanda Fears, and we called ourselves Purple Lady Productions. We used several restaurants where we would have a special night with a lesbian musician or group performing. The largest thing we did was a Lucie Blue Tremblay concert. Several times, we had Alix Dobkin here, and I helped Suzanne Keller with a couple of those. I don’t remember if we used the production company for that.

The women’s festivals were important from early on. It was such a great way to get together to have experience and promote growth in lesbian culture. It was one of the ways that people connected. I’m glad that CampOut has carried on that tradition.

BM: The women’s festivals that were here in the 1970s included music and workshops and other activities, such as information tables. These were one-day events held outdoors. While music was a part of it, we wouldn’t call them music festivals.

In the 1980s, Richmond Lesbian Feminists did lesbian feminist festivals. They were weekend events, starting on Friday night and ending late Saturday afternoon. We did them at Pocahontas State Park. We would rent a whole section of the campground, with cabins, a large meeting space, and a kitchen. Many people would camp out or stay in cabins. These were specifically lesbian festivals, though we advertised them as open to all women. (Almost everything we did was open to all women.) Music would be part of that, but it wasn’t like a music festival.

Many of us had been to women’s music festivals, like Michigan, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, one in Pennsylvania called Sisterspace, and one in DC called Sisterfire. When In Touch. which later changed its name to CampOut, was starting out, they were a year-round, women-owned, camping place that was most of the time for women only. They did some family events that would include male children, things like that. Once a year, they did a women’s music festival, which they still do. It’s a weekend event. It’s a camping experience, not nearly as large as Michigan. They have roofless, outdoor, cold-water showers. They have some cabins and a lot of space where people can set up tents and camp. Also, they can accommodate RVs.

Credit: CampOut.

They have several performance spaces, including a major stage where things are going on all weekend. There are smaller venues within the camp for things like drumming workshops. Friday and Saturday nights, they usually have a women’s dance and a big, campfire circle. They provide food, and people can bring their own food. They have several hundred people, probably never more than five hundred. They have a lake for swimming, boating, and fishing. It’s stocked with fish. There’s a lot of stuff to do there. They have vendors selling women’s crafts. That would be really a women’s music festival.

The woman who started In Touch was named Janet Grubbs. She organized women’s outdoor concerts that she called festivals. With those, she was trying to raise interest and raise money for the projects she wanted to do. She set up a corporation and women could buy shares in it. They sold enough shares to buy property. They bought nearly 100 acres in Louisa County, about halfway between Richmond and Charlottesville. It was women owned, intended as women’s land.

This was not a place where women lived year-round. Usually, somebody would live there as a caretaker, but there was never a group living there all the time. A group of lesbians had built cabins and cleared land for the lake. That group was eventually called the Crew. I was part of the Crew, and I helped to cut down trees, and helped to build cabins there. From early on, they also had a second weekend-long festival. The women’s music festival was Memorial Day weekend in May. On Labor Day weekend in September, they would have a country-western event, called the Wild Western Women’s Weekend. This one was smaller than the Memorial Day women’s festival weekend, but still had a good turnout.

Then they had various other events, and those changed a lot over time. Through most of the year, they offered a women’s campground where you could rent cabins or do tent camping. You had to arrange it ahead of time. When they weren’t having events, it was a campground, and it still is.

At some point, there were differences of opinion, so In Touch dissolved and sold the land to some women who had been part of In Touch. They bought it to continue having women-only space and the women’s festivals. So, that became CampOut. They’re still there. They still have the Memorial Day festival, the Wild Western Women’s Weekend, other events, and camping space for women.

BM: I’d like to talk about how Richmond Lesbian Feminists were instrumental in many efforts at building coalitions. Here’s a timeline of significant events.

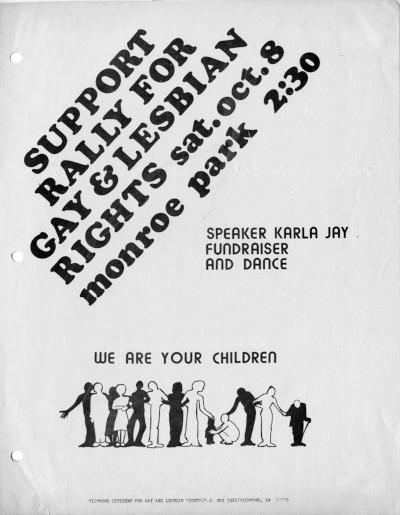

Lesbian and Gay Rights Rally in Monroe Park, 1977

BM: In the 1970s, I was on the board of the National Women’s Political Caucus, and Bobbi Weinstock was on the board of what was then the National Gay Task Force (now the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, or NGLTF). Because we had that kind of involvement, we would also know about things happening other places.

That was partly how we were able to organize a response to an Anita Bryant event.* In many places, people were having demonstrations against her. What we had heard about her antigay events, we didn’t really like very much, and these were also often very antiwomen. There would be signs referencing body parts, basically very sexist content. We did not want to have that in Richmond. We organized a coalition of different groups here to talk about how to respond to Anita’s visit in a way that would benefit us and take the attention off her.

We came up with a Lesbian and Gay Rights Rally in Monroe Park. We had close to two hundred people at that event, a pretty good turnout, even though it was drizzling rain. We had some national people there. Karla Jay spoke. We had pretty good publicity, and we had some religious organizations that were part of our coalition.

A few people still went to protest Anita Bryant, but it was a small number of people. Most of the people came to our rally, and we got very good press coverage. Instead of focusing on Anita Bryant, we focused on our community and what our interests were. We gave Richmond their first, public view of our community doing something positive. There were certainly a few people there with signs referencing Anita Bryant. But the overall focus was more on our desire to have our rights recognized.

[* In 1977, Anita Bryant led a crusade to overturn an antidiscrimination ordinance in Dade County Florida. It was called “Save the Children,” claiming that lesbians and gays recruited children to be homosexuals, presenting a danger to society. Lesbians and gays organized to prevent the ordinance being overturned, and this activism spread across the nation. Although the ordinance was overturned, the activism around it continued. This is seen as a watershed event akin to the Stonewall riots in 1969.]

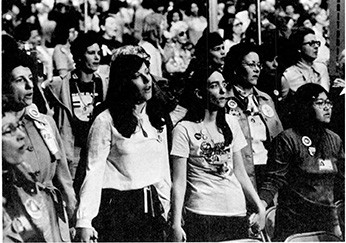

International Women’s Year Planning, 1977

BM: International Women’s Year (IWY) is another example of coalition building. We were able to get involved in the early stages to organize that. We knew what had happened in other states when women that I call the “antiwomen women” organized against the various issues, including against lesbian rights. We organized very effectively with the Virginia International Women’s Year group. We had a workshop at that event with the intent to put forth a position on recommendations for lesbian rights, which the entire group endorsed. We elected lesbian delegates [to the national IWY gathering in Houston, TX, that year, 1977], and I was one of those delegates. Overall, we had a much better experience here in Virginia.

This International Women’s Year in Houston, Texas, in 1977, was really a defining moment for feminism and lesbians. For the first time, a lot of feminist groups and feminist leaders realized that it was lesbian participation that turned the tide at these meetings and that made it possible for feminist issues to reach that national meeting.

I could tell a difference in that day of meetings here. About halfway through the day, there was a difference in what people were doing. The ERA Ratification Council had always been uncomfortable with lesbians, and it had had a slate of people put forth as delegates to the national meeting. Halfway through the day, they approached me about being on their slate. That’s just a small example. There was really much more than that. There was really a turnaround in perceptions. At this Houston meeting, even Betty Friedan, who had been one of the worst, began to backtrack a little bit. They were no longer in opposing lesbian issues and lesbian visibility in the women’s movement. That was very significant for lesbian feminists all over the country. What happened in Virginia was replicated in other places.

Because Bobbi Weinstock and I were on national groups, that was one of the reasons we were able to be effective in our involvement with the Houston meeting. We also benefited from our connection to Bessida White, who was appointed by the governor to be on the Virginia commission that was working on International Women’s Year. Bessida White was very open to working with us in order for us to have more participation.

The original outline for the national plan of action did not include lesbian issues even though the national group did include Jean O’Leary. I believe that Jean O’Leary was at that time director of NGTF [she was co-executive director, with Bruce Voeller]. She was possibly the first out lesbian or gay person to be appointed to a commission by a President. [President Jimmy Carter appointed O’Leary to the presidential commission on International Women’s Year. Wikipedia says she was the first openly gay or lesbian person appointed to a presidential commission.]

The plan that was approved in Houston did include lesbian issues. One thing was general discrimination issues facing lesbians. One was doing away with sodomy laws, which affected women in terms of child custody. The argument for taking custody of their children was by claiming that lesbians were guilty of sodomy [sodomy was anything other than narrowly-defined, “normal,” heterosexual intercourse]. The whole issue of child custody was very big. Those three issues, general discrimination, sodomy, and child custody, were included as part of NGTF’s strategy. The strategy was that in every state meeting, they would pass similar things, even including the wording pertaining to lesbian life. That made it easier to get these issues passed at the national level.

Virginia Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights

BM: We also helped to organize the Virginia Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Bobbi Weinstock and I were very active with that, along with other lesbian feminists. That group met regularly to share information about what was happening all over the state. It was politically oriented, and it had a volunteer lobbyist. They laid the groundwork for what would later become Virginians for Justice, a political lobbying group that is today Equality Virginia.

One of the things about Richmond Lesbian Feminists is that while we were doing all these other things with lesbians in Richmond, we were also very engaged with the wider community. We very much wanted to work with other groups, with feminist groups, with LGBT groups, and with civil rights and human rights groups. That was an important part of our lesbian culture. Lesbians often have a broad agenda about social justice.

Jacqui Singleton, Richmond Singer/Songwriter/Playwright (1955-2013)

BM: Jacqui Singleton was a good friend of mine. She was African American, originally from the Tidewater area, and she had gone to Longwood College, which had been a predominately women’s college [it went fully coed in 1976]. She was a singer, songwriter, and playwright.

Jacqui Singleton performed at the first gay pride event here in 1979, and she continued to be active in the community for the rest of her life. She was in a group called the Richmond Jazz Ladies in the 1970s.

She played the guitar, and she often performed by herself, as well as putting together bands that played at festivals. You can download some of her music from YouTube. [The YouTube video includes an interview and her song “Liar.” The video is described as “from the second broadcast season of Network Q Out Across America, which originally aired on public television in the United States.”]

Jacqui Singleton was involved with Richmond Lesbian Feminists at various points. In the book,* we have a picture of her playing with her band at our New Year’s Eve dance on the eve of 2000. [*Lesbian and Gay Richmond (2008), p. 113.]

Jacqui also was very involved with writing and producing plays. The Richmond Triangle Players was started in 1992 by three gay men who put on a series of one-act plays by Harvey Fierstein, Safe Sex Trilogy. They weren’t yet the Richmond Triangle Players. It worked so well that they started what would become the Richmond Triangle Players. At that point, Jacqui Singleton was on their board, and she directed her own play, Manny & Jake, as their first full-length production. They were doing plays at an after-hours LGBT bar, Fielden’s, in Richmond. They eventually had their own space. Jacqui was involved with them from early on, and she was eventually considered a board member emerita.

Jacqui also produced plays on her own. She put together a production company called JERA Productions. I worked with her on that, scouting for scenery and props, and I helped to promote it. She produced several of her own plays at various venues, including Babes of Carytown, the local lesbian bar. She also produced some plays by other playwrights, including the celebrated, prolific, lesbian playwright, Carolyn Gage, who grew up in Richmond, and who no longer lives here. Carolyn Gage also writes one-act plays, and we produced several of these.

Jacqui Singleton also wrote a series of lesbian science fiction stories which were published, sword and sorcery tales, and some lesbian fiction that she published as well.

She was quite talented in many different areas. Toward the end of her life, Jacqui Singleton had some major health issues, unable to do as much. She died in 2013. Toward the end of her life, when she was more limited in what she could do, she was a member of MCC church here. She helped them do their Christmas play and pageant every year, and she remained actively engaged until the end of her life. I would consider her one of the founders of Richmond Triangle Players, but I guess it depends on how you interpret their history.

Sharon Bottoms Custody Case

BM: In the early 1990s, Sharon Bottoms had a lesbian relationship with April Wade that led to Sharon losing her young son. Sharon’s mother had gone to court to take away custody, solely on the basis of her daughter being a lesbian. Sharon did something that few lesbians did. She decided to appeal that decision. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) represented her, and they got it overturned at the first appeal level. But when the Virginia Supreme Court heard that appeal, they took custody away from her again.

Richmond Lesbian Feminists were very involved with the effort to restore custody to Sharon Bottoms. We offered support for Sharon and her partner, April, because their own families were not being supportive of them. We did a number of fundraisers and other things to help them out. The ACLU covered their legal costs, but we helped in other ways. That was one of the things that Richmond Lesbian Feminists and Lesbian Womyn of Color did together, a fundraiser at Club Colours.

A lot of people had negative feelings about that issue because it put into people’s minds that you could take custody away from somebody. But the reality was that this had been an issue since the 1970s.

Very few women would appeal custody verdicts due to the fact that at the level where you lose custody, it is handled in family court, and it remains a sealed record. It doesn’t get into the news. Once you appeal it, though, it becomes public record. A woman who did it several years after Sharon Bottoms did it as a Jane Doe; she didn’t use her own name. It was very courageous of Sharon and April both to be involved in very public scrutiny in trying to regain custody of their child. While tragically, they were not successful, they did make people more aware. The average person had no idea that lesbians were losing custody of their children. Lesbians knew about it, but not the average person. It’s amazing how many women would come up to Sharon Bottoms’s mother to say that they couldn’t believe a mother would do that to her daughter. I think it had national impact in getting people to change their views.

There was so much going on in the 1970s. It’s phenomenal to look back at all that.

BM: Richmond Lesbian Feminists has also had political involvement. We’ve supported things that the Virginians for Justice group and the Equality Virginia group does. We never incorporated for good reason. It was discussed several times, and we always decided not to incorporate. While we are organized for non-profit purposes, we do occasionally take political positions.

There was so much going on in the 1970s. It’s phenomenal to look back at all that. One of the organizers of ActUp was a member of Virginians for Justice. Leadership in feminist organizations were often lesbians, and I think that was true for everything. Organizing around the AIDS epidemic involved a lot of lesbians and a lot of lesbian caregivers. A local women’s golf tournament is organized by lesbians, and it has mostly lesbian participants. That raises a large amount of money for the Virginia Breast Cancer Foundation.

There is another Black lesbian women’s group active now, Women of Essence. [See them on Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/Women-of-Essence-Inc-530817617023657/] That group is led by a woman named Luise Farmer. That group has organized mostly events to raise money for breast cancer, including an annual dance. They have now joined with Richmond Lesbian Feminists in their New Year’s Eve celebration.

Another group that has joined with us is GRITS, which is Girls Rolling in the South. They are women bowlers. I don’t believe it’s all lesbians, but there must be a lot of lesbians in the group. They have partnered with us for the New Year’s Eve program for a number of years.

Timeline of Richmond Lesbian Feminist Activism

1971: Virginia Women’s Political Caucus has an organizational meeting attended by Beth Marschak and another student at Westhampton College, University of Richmond. Together, they start the Organization for Women’s Liberation at Westhampton. Marschak is active in the Women’s Political Caucus, both at the state and national levela, for sixteen years, serving on their national steering committee for much of that time.

Winter 1974: Beth Marschak and Stephanie Myers announce the beginning of Virginia Lesbian Feminists at a workshop at the winter meeting of the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus (VWPC). Initially, a statewide organization with chapters in Richmond, Tidewater (Norfolk area), and Charlottesville, the statewide organization failed after a year. The Tidewater chapter did not last the year. The Charlottesville chapter lasted into the 1980s, but failed due to financial reverses when a venue booked for an event broke a contract. The Richmond chapter in 1975 became the Richmond Lesbian Feminists, and it celebrated 40years in July 2015. (From Shepherd’s thesis: “Although Marschak had originally intended for the group to operate as a lesbian caucus for the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus, mirroring the structure of the national organization, she quickly surmised that many of the women who attended were there not as feminist activists, but simply because the group offered a social alternative for lesbians. …As a result, RLF began not as a political organization, but as a social option for lesbians.” p. 30.)

July 13, 1974: “The first Richmond Women’s Festival was held in Monroe Park… Women’s organizations from Richmond and across the state attended the event. Speakers included Margaret Sloan and Florynce Kennedy, founders of the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), and novelist Rita Mae Brown… The Richmond Women’s Festivals were the first in the city of outdoor, public festivals with a sense of lesbian or gay pride.” (Caption to poster, p. 42, Marschak and Lorch). Kay Gardner performed. Richmond Women’s Center and the Third District Women’s Political Caucus organized it, with support from several other organizations (NOW, WILPF, and others). This is before RLF was formed, which would have its first meeting in July 1975. RLF participates in organizing two more women’s festivals, 1975 and 1976.

July 1975: Richmond Lesbian Feminists (RLF) meets as a group for their first meeting, held at the Richmond Friends Meeting House (the Quakers are known as the Friends). RLF came from a statewide organization, the Virginia Lesbian Feminists. It began at a state workshop led by Beth Marschak at the Virginia Women’s Political Caucus (VWPC) in winter 1974. Marschak and Stephanie Myers were founding members of RLF. For some years, Myers had been wanting to start a local, lesbian organization for social purposes; and she was not interested in the women’s movement. Marschak was very involved with the VWPC and also with the Women’s Center in Richmond, organizations deeply involved in the women’s movement. Myers left RLF soon after it started. RLF celebrated its 40th anniversary in July 2015. Their newsletter is the Richmond Lesbian Feminist Flyer (“The Flyer,” 1975-present), edited by Beverly Rainey. SEE: Prentiss, 2015.

August 1976: Our Own Community Press began as a newsletter of a newly-formed gay and lesbian organization Norfolk, Virginia. It soon began publishing as a statewide newspaper, working from an office in a Unitarian Universality Church. It went bankrupt and closed in August 1998. “At the time it ceased production, Our Own Community Press was one of the country’s oldest, existing, gay and lesbian newspapers.” (Caption to photo of front page of first issue, p. 48, in Marschak and Lorch.)

October 8, 1977: Lesbian and Gay Rights Rally in Monroe Park was organized by RLF and other LGBTQ and ally groups on the same night that Anita Bryant was speaking in Richmond on her “Save the Children” homophobic crusade. This rally was designed to direct attention away from that event and toward the lesbian and gay community in Richmond, and to gain positive press for the lesbian and gay issues.

April 9, 1978: Opening night celebration at Labrys Books, Richmond, VA. Founded by Theresa “Terri” Barry and Joan Mayfield, Labrys Books “sold books and music by and for women. The store also served as a meeting space for feminists and lesbians.” (Caption to flyer, p. 62, in Marschak and Lorch.) It closed in 1981, to be replaced by WomensBooks, which opened in YWCA space in downtown Richmond, later moving to the basement of a food co-op in the Fan District.

June 23, 1979: Richmond, Virginia had its first Lesbian and Gay Pride event. I think it is important that in the 1970s, the rallies and gay pride included lesbian in their names. That did not merely “happen.” We advocated and fought for it.

1980: Virginia Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights (VCLGR) elects Beth Marschak “to speak for their interests as a registered lobbyist at the Virginia General Assembly. She was the first person to lobby the Virginia legislature on behalf of LGBT rights.” VCLGR was founded February 25, 1978. (Caption to photo, p. 53, in Marschak and Lorch).

1981: WomensBooks opens after Labrys Books closes in Richmond, VA. “WomensBooks was a feminist-owned bookstore cooperative that started at the YWCA on North Fifth Street in the winter of 1981… [and it] later moved to the basement of Fare Share Food Co-op at 2132 East Main Street. …Shortly after that, Phoenix Rising bookstore [a gay and lesbian bookstore] opened in 1993, and WomensBooks closed.” (Caption to photo, p. 63, Marschak and Lorch.)

1984: Jacqui Singleton, an African American singer, playwright, and novelist from Norfolk, Virginia, founded the Arts Alliance, “a theater group under the wing of the Richmond Department of Recreation and Parks, which produced several of her plays, including The Breaking,” (Robertson obituary of Jacqui Singleton, d. 2013). Singleton was also a cofounder of Richmond Triangle Players, the LGBT theatre troupe founded in 1992.

August 1987: Richmond lesbian, Beverly Rainey, becomes editor of The Richmond Pride, originally the newsletter of the Virginia Gay Alliance. By then, it was a newspaper with a large readership. Rainey had been a reporter for the paper since it began in 1986. It ceased publication in 1990. Rainy also edited the Richmond Lesbian Feminist Flyer, the newsletter of Richmond Lesbian Feminists (RLF), 1975 to the present. (Caption to photos, p. 84, Marschak and Lorch.)

1992: Jacqui Singleton, an African American singer and playwright, directed her play Manny and Jake as the first Richmond Triangle Players full-length production. (They had previously produced a series of one-act plays by Harvey Fierstein, Safe Sex Triology, before they had formally formed the company.) RTP was a gay and lesbian theatre troupe begun in 1992 by three gay men (according to Lesbian and Gay Richmond), and Singleton was on its board from the beginning. “Jacqui also produced and directed a number of plays, including her own work and that of others, through her production company JERA Productions.” Jacqui Singleton died in 2013. (Quote is from Beth Marschak’s obituary for Singleton, posted to the RLF Facebook page December 15, 2013.) See also photos of Jacqui Singleton, p 113, of Lesbian and Gay Richmond. From Robertson obit: “Two plays, The Crazy Man in 1982, and later, The Breaking, were produced off-off-Broadway. Others were staged at the University of Connecticut, Philadelphia’s New Freedom Theatre, Virginia Union University. and the now-defunct Children’s Theatre of Richmond.”

March 1993: Sharon Bottoms loses custody of her young son because she is a lesbian. Bottoms and her partner April Wade contested the initial decision, which was very unusual, since family court appeals became public. The ACLU took her case to the first level of appeals, where the initial decision was reversed. Ultimately and tragically, the Virginia Supreme Court upheld the custody decision. RLF supported Sharon Bottoms and her partner, and the publicity brought attention to an issue that most people were unaware existed. (See p. 97 in Marschak and Lorch).

1993: Lesbian Women of Color (WOC) is active in Richmond, VA. “Lesbian Women of Color (later, Lesbian Womyn of Color) was organized by Terrie Pendleton in the early 1990s. The group provided a range of activities from potlucks and raps to teas and dances.” (Caption to poster, p. 100, in Marschak and Lorch). Another group followed them, Gatekeepers. They had a newsletter, and they were active for a few years.

1994-present: In Touch (later named CampOut) begins having activities on 100 acres of women’s land in Louisa County, between Richmond and Charlottesville. Memorial Day weekend women’s music festivals and Labor Day Wild Western Women’s Weekends continue to this day.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.