Gerry Green of Amelia’s Bookstore

Barbara Esrig interviewed Gerry Green on March 16, 2015

Gerry Green cofounded a feminist counseling service and established Amelia’s, a feminist bookstore, both in Gainesville, Florida, in the 1970s.

Barbara Esrig: What brought you to Florida?

Gerry Green: My partner at the time and I went down to south Florida, to Okeechobee. I taught at a community college in Fort Pierce, Florida, for two years. In 1972, I went to Santa Fe College in Gainesville, Florida, to teach in the nursing school.

BE: What year and where did you come out?

GG: I came out in 1950. I had gone to half a semester at Texas State College for Women (TSCW). We were having a party at a motel. I don’t know why I was asked to arrange it. A lot of TSCW women were there (at the time, I probably called them “girls”). It was my first year in college. I noticed a cute little kid, and I had no idea what was going on with her. We all got to drinking and carrying on, and that’s when she kissed me, and that was it. I mean, that was how I came out.

BE: Did you have a name for lesbianism at that time?

GG: You know, I was so guilty and afraid. We didn’t talk about things like that in those days. We didn’t use the word “lesbian” or anything that would identify us as anything other than straight. I didn’t talk to anyone about it. And although things kept growing in that area [more lesbian visibility was occurring], none of us talked about it, even at parties.

Biographical note

Gerry Green cofounded Breakthrough Counseling Center, a feminist counseling service in Gainesville, Florida, in 1975 or 1976. She also cofounded with Carol Aubin the feminist bookstore, Amelia’s Bookstore, in approximately 1977. Breakthrough Counseling Center shared space with Women Unlimited entities such as the radical newsletter, WomaNews, and with Gainesville’s first feminist bookstore, WomanStore. Amelia’s was a successor to that first bookstore, located in the old Tench Building where the first Women Unlimited was located.

Where we met in those days was the softball diamond and the bars. Yes, only certain bars [the ones that were relatively safe for us]. We had to be very careful because the bars got raided [by the police] a lot. We’d have to run out the back door. In fact, one time I ran out the back door of a bar that was in the country, way out in the country, in San Antonio. When the cops came, we had to run out that door. And we ran through barbed wire, and all of us got scraped up, and we kept on, whatever.

BE: Were you raised in California?

GG: Yes, I’m from California, but I went to school in Texas. My mother died when I was four, and my dad remarried. We went to Fort Worth, Texas. We ended up in Dallas, Texas, where I graduated from high school. It took me about ten years to get a bachelor’s degree. Instead of studying, I played bridge, drank beer, and got kicked out of college. I actually got kicked out by the people who were probably the most “dykey” in the world: it was a women’s college. I was a late bloomer of sorts.

BE: What happened after you got kicked out?

GG: After I got kicked out, I went into the service. Two years, four months, and 21 days later, I wound up at Lackland Air Force Base [in Bexar County, Texas, near San Antonio, Texas]. For some reason, I was red-lined at the time, which means that after you get out of basic training, they keep you in one place until they decide what they’re going to do with you. They were waiting on my orders or whatever. You know, those were the days when they would put you in a room, under a bright light, and question you for being homosexual.

One night, I got a call at 9:00 pm, and then, these two guys came to my barracks, I had to go with them to this room, and they put a light on me, a bare light bulb hanging over my head, exactly like you see in the movies. And they asked me, “Where were you on “blah, blah, blah” night?” And it just so happened that I hadn’t been on base. They kept on questioning me. Finally, I don’t know where I got this idea, and I said, “I’m going to get a lawyer.” In those days, you didn’t get lawyers. Amazingly, they quit at that point. They quit questioning me, and I never heard from them again. Though it was pretty scary. All of us were thinking that we were going to get kicked out. And some of them did. I happened to be lucky. It was in the service when I found nursing, and it was what I wanted to do. You know, our paths in life are very interesting.

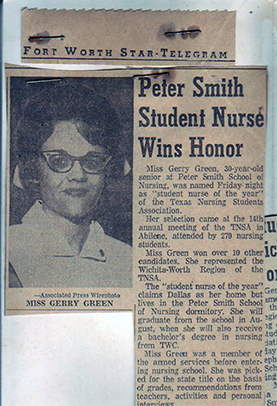

In 1955 or 1956, I got an early release to go to nursing school. They would let you out early if you wanted to go to medical school. Not for nursing school. For some reason, the chief nurse at the air force base made that release possible for me. I owe her a debt of gratitude for that. I went into nursing in Fort Worth, Texas, graduating from a diploma program. It was a three-year program connected to a hospital [John Peter Smith Hospital School of Nursing], a charity hospital in Fort Worth. I was the last to get that program’s diploma. After that, they started the two-year program, and that was a big thing throughout the United States.

When I graduated, I was voted Student Nurse of the Year in Texas, which is kind of interesting. Actually, it was a great thrill for me. I was the program chair and president of the Wichita-Worth Region, Texas Nursing Student Association.

Upon graduating, the John Peter Smith [Hospital School of Nursing] asked me to teach. So, I taught for five years at the same school where I graduated, working evenings at another hospital [Harris Hospital].

In the middle of all this, I got married to a man. Well, that only lasted about a year and a half. Attempting the straight life did not work for me.

BE: What kind of nursing did you do?

GG: It was general nursing because no specialties existed at that time. We did everything at that hospital. There weren’t enough nurses. I also worked part-time at another hospital [Harris Hospital] from the one where I taught [John Peter Smith Hospital School of Nursing]. I worked the 3-to-11 shift as a staff nurse in this other hospital while I was teaching mornings. I always thought it was good to work while you taught in order to stay current with what’s going on. Next, I went to Austin, Texas, where I got my master’s degree in nursing.

Here’s a funny story that goes with me getting into the nursing graduate program. I took the GRE [General Record Examination, the common graduate school entrance exam in the USA] twice because the math part blew me away. I did OK on the verbal, but not in math. It seemed a good idea to take a course in “new math” to help bring up my math score. That made my math score go down lower! The “new math” confused me totally. How I finally got into the university is an interesting story, and I’m sure a lot of people have stories like these.

I met at a convention one of the deans, a woman, of the University of Texas at Austin. I was very active politically in nursing at that time. I’ve always been politically active in causes I’ve been involved with. Anyway, we all got tipsy one night, and she and I were having a conversation. I asked her, “Why won’t you let me in the program?” She said, “We’ll let you in, and if you do OK after the first year, you’ll be all right.” And so that’s how I got into the master’s program by having a drink with another dyke! Isn’t that funny? That proves that connections are everything. I went for my master’s and I got it.

That was a pretty radical thing for me as a woman to get a master’s in nursing in those days, and I wanted to learn more. Nursing was definitely the thing for me, and I was very fortunate to find something I really loved. And since I was so politically involved, and since things were changing in education as to what degree was good and what wasn’t, I wanted to get a master’s degree. That way, I could assure myself of a teaching job at some level and also continue to learn. It was like a path.

When I went down to Austin, Texas, I went with a really good friend who taught with me, Carl Graves, a gay guy. We were buddies, and I loved him dearly. He’s dead now. We went together, and I was going to major in medical-surgery nursing since that’s what I had always done. I’d been teaching fundamentals of medical-surgery nursing. I taught obstetrics nursing once, and that was pretty scary.

I found myself standing in this huge place: the University of Texas at Austin, and there was the medical-surgical table, and there was a psychiatric table. And I looked at the medical-surgical curriculum and I thought, “Why do I want to do that?” That’s all stuff that I’ve already done and I had worked in that field. In those days when we worked in nursing, I mean, we did everything. We had to learn it on the fly, do you know what I’m saying? I decided to do psychiatric nursing. And so did Carl. He and I were laughing so hard about why we were doing psychiatry since we hated it. We decided to do it, and we did it. And it turned out really, really well.

BE: What did you do after you graduated?

GG: When I got out of graduate school, I had not yet finished my thesis, and I was looking for a job. They offered me a job at Baylor University School of Nursing in Dallas. I taught there for a year. I had one year teaching at college level under my belt. Then I was going to move with my partner.

I had come to the University of Florida, and I talked to Bobby Dykes. You probably don’t know her. She’s dead now too. I went to interview with Bobby, and she was really good. She was also a dyke. Yes, and her last name was Dykes. Of course, we were all closeted. You have to know that. Nobody ever talked about it even at that point. Anyway, Bobby said, “Gerry, you’re not going to be happy here.” I asked her why, and she told me that they were old school, very old fashioned. They were very Freudian in their psychiatric program at the University of Florida. She told me that I had better think about going into a two-year, Associate in Science in Nursing (A.S.N.) degree program because it was really new. She told me that I could create a lot of newer things rather than having to stick with the old, Freudian kind of psychiatric stuff.

I left and went back down to Okeechobee, Florida, where I had come from. My partner at the time was from there, and I began teaching psychiatric nursing in nearby Fort Pierce, Florida. Yes, I’d had a partner. She was not my first. My first partner, I met while I was at Texas State College for Women. We were together for about five or six years. And then I was without a partner for a good little bit, and I had kind of messed around, actually. All of us did at that age. Then I met my partner of twelve years. All of her family was in Florida, and that’s why we went to Okeechobee.

BE: Was her family okay with you two being a couple?

GG: Oh, no, they had no idea. We were not out. She’s still not out. We were “roommates.” So, I got a job down in Ft. Pierce teaching at Indian River Community College. There were only three faculty members. It was very small, and they needed a person, which was why I went in. I was there two years, teaching psychiatric nursing. When the person who was the head of it left, they put me in charge. They had not had any good passing scores on their boards. They were terrible.

BE: What was it like being in charge?

GG: I created a new curriculum, and I also created a lot of havoc. Why? Because they hired people without talking to me or asking me. This young guy came up in shorts and a little t-shirt one day and said to me, “I’m your new faculty member.” And I said, “Say, what?” They also got after me for having our students sit with patients when they were dying, allowing the patient to cry. It was that sort of oppression that was going on. They didn’t want us to do that. The president called me in to review this new curriculum I had done, which by the way, my students who took that curriculum were the ones who were passing the boards, 100% of them. He called me in and said, “Gerry, we just can’t do this.” And I said, “No, I can’t do it either.” So, he and I would sit in this library to stuff envelopes [administrative work] after they had taken me out of my position. He and I would discuss two or three times a week how ridiculous things were, but he had no choice.

In any case, at a meeting, I met Carol Bradshaw, who was head of the program for the associate degree in nursing program at Santa Fe Community College (SFCC), in Florida. I told her that I wanted to come work in her program, and she told me to come. I did. It was 1971 or 1972, and soon, a lot would be going on. It was the beginning of new things happening at Santa Fe Nursing School, too, like therapeutic touch, and those kinds of things that Carol brought in to the program.

BE: Women started getting together in consciousness raising (CR) groups in Gainesville, Florida, in the 1970s. Soon, women were setting up outreach and services to local women. You were instrumental in that. Can you tell me more about it?

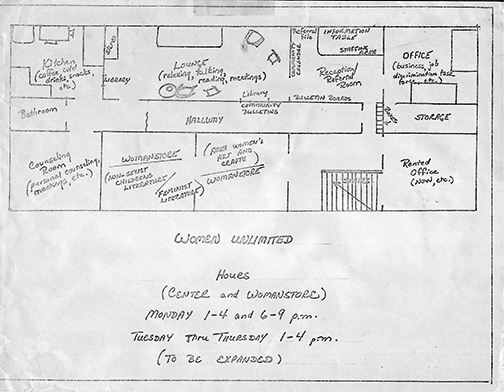

GG: In 1975, a group of women, including Rosalie Miller, Linda Bassham, Judy Koons, and Jan Hahn, formed an umbrella organization called Woman Unlimited, which ultimately would include Womanstore, the first feminist bookstore in Gainesville, WomaNews, a radical feminist monthly newsletter, and the Women’s Center, where women could meet and organize.

Judith Brown was a radical feminist lawyer here in Gainesville. She moved out of her office, giving that space to the women who wanted to start Women Unlimited. It was an old, historic building called the Tench Building on South Main Street. That’s where Women Unlimited started. Then a couple of us wanted to set up an alternative feminist counseling center for women. We needed a place to put our office, and we met with Rosalie Miller and Linda Bassham to have a discussion with them. It all worked out really well, and we began renting a room in that same building.

With Breakthrough Counseling Center, we were dealing with women’s issues within a feminist perspective, whatever the issues were. We worked with men, also. Breakthrough moved to a new building that was named Amelia’s Bookstore. SPARC (Sexual and Physical Abuse Resource Center) had used the space for a little while early on when they had no place else to go. Marcia West would come in and volunteer for them, and they’d do some things back in that Breakthrough office.

BE: What influenced you to become political?

GG: We were there to support women. And we started CR [consciousness raising] groups for women. It was really something. That was the beginning of the Breakthrough Counseling Center. And that was the beginning of my coming out and of understanding myself more. When I read Feminism Is Therapy, by Florence Rush, it changed my life, totally changed it overnight. And that’s when I became involved in the politics.

I began reading books, and there was a lot written in those years about feminist therapy. However, it was not accepted, you know, by any of the colleagues that I worked with at the university. When I read that book, it made a difference for me. I can’t remember how that transition occurred. It’s as if I woke up one day, and it was a realization that this is why I had been so miserable all these years.

Feminism Is Therapy talked about the social issues of women, and why women were oppressed. It explained what that did to us, why we’d fight with each other, dislike each other. All of those very basic things we’d been socialized to do, unraveling. I began to understand our relationships with women that we take for granted now. I had no idea. I was raised in a John Birch family.

All this naturally affected the relationship I was in. We broke up.

BE: Getting involved with feminism broke up your relationship?

GG: Well, I came out. I was coming out as a dyke, and was that was too much for her? Oh, yes, it was way too much for her.

It wasn’t like I woke up and said, “Oh, by the way girls, I’m a lesbian.” I just decided not to hide it any longer, and if somebody asked me, I would be honest. Of course, in those days nobody asked you because nobody knew they could ask.

That’s when they opened the Women’s Center. We made the deal about having an office there, and that’s when I started getting political. I remember Rosalie saying “Come to the parade,” and I said, “OK.” I went to Tallahassee. She came up to me and put an armband on me. It was the ERA parade. I didn’t have a clue about what she was talking about. I did not know until later. She said, “Wear this.” I said, “OK.”

BE: What did the armband say?

GG: It didn’t say anything. It was like the armband to show that we were compadres. We marched. After that march, almost everything was changing in my life.

We moved the Breakthrough Counseling Center office over to the Women’s Center, upstairs. Also upstairs was WomaNews, the newspaper. I was not involved with WomaNews. We wrote articles for it and things like that. Those women were Abby Walters (I think), Jan Hahn, and Sallie Harrison. Those kinds of folks really were the ones that wrote a lot. We started with Breakthrough upstairs, and then we moved it downstairs after we got the bookcases built and everything. I remember Diane Cuppy when she was building those bookcases. She was a great carpenter. And they got tables and all of that stuff. That was all Bonnie Coates’s stuff, and it all came together. We did all that over the next couple of years.

BE: How were you paid?

GG: We got CETA funds.[1] When we did the newspaper, CETA said we were not following the law, and they jerked the funds out from under us. When CETA gives you money, you’re not supposed to be political in any fashion. The real reason was that they were ready to find anything to get rid of us.

BE: How did you get the money from CETA in the first place?

GG: Jan Hahn. She was working at the Women’s Center at the time, and she wrote a grant. That’s how we got it. And the City Commission were jerk heads! There was one in particular who didn’t like us, Ed something, and they jerked that money out from under us. WomaNews and the Women’s Center died because the funds ran out. There is only so much volunteering one can do. We all got burned out.

Women Unlimited had a congenial relationship with the Women’s Health Center. We did things like work on the first Southeastern Women’s Health Conference in Gainesville [Florida]. We worked hand in hand with the Women’s Health Center for that.

BE: What was the Southeastern Women’s Health Conference like?

GG: It was really something big. We all got together, and we decided that we would deal with incest, with rape, with sexuality, and with health issues of all kinds. We had 92 workshops. We held it at the Reitz Union [on the University of Florida at Gainesville] campus. When the university found out what we were about, and that maybe 10,000 million or so lesbians [laughing] were going to come from all over, they got scared. They told us, “You can’t have it here.” Judy Coons, who was our attorney, told them that they had signed a contract. And she took care of it so we had it at the Reitz Union.

We had amazing major speakers. Rita Mae Brown, Barbara Ehrenreich, Pauline Bart, Phyllis Chessler. I think, actually, 700 or more people came from all over, mostly from the South, and even a lot of the Boston [Massachusetts] women came. They had just published Our Bodies, Ourselves a couple years before, and that’s how we got the idea to invite them. The women at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center had gone to Boston, where they got the idea from those women who wrote that book. They brought the idea back to our feminist community. Pam Smith was involved in it.

BE: Was Judith Brown involved in that?

GG: Judith Brown? No, not involved. That was early on. Rita Mae said that we all needed to come out. And she kept saying, “If you come out, it’s going to change things.” Now that was something like fifty years ago. And so, look what’s happened in the last four, five years. Everybody is coming out. She was right to start with. We did have the first workshop about incest, I think, in the country, which was really good. We dealt with that in the women’s health center and at Breakthrough Counseling Center a lot.

BE: How did the bookstore start?

GG: Ann Gill had a few books in the Tench building. At that time period in civil rights and in the women’s movement, it was very important to have a missive of some sort. The written word was really, really important. We decided that we wanted to start a bookstore since several of us that ran the Women’s Center where Rosalie was the director and several of us were involved on the board.

I don’t think we called it a director or a board in those days. Everybody was supposed to be equal. You know, the way lesbians organize. We called it the steering committee. We decided to carry women’s books. We also decided to make the big decision to carry children’s books so that the younger girls would grow up with better images coming from the kind of books that would give them more self-confidence. That’s how the bookstore started, and we named it WomenBooks.

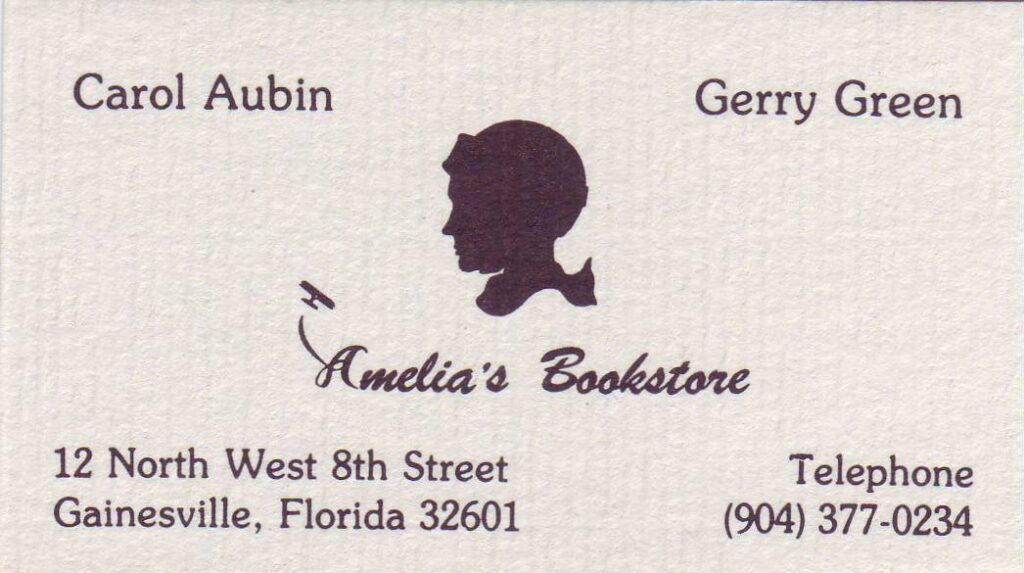

I got involved with the bookstore, and after a couple of years went by, we needed to move. A well-known realtor in Gainesville that we knew before we rented the Tench Building, who was really interested in feminism, found a building for us. A bunch of women put money into that building off North West 8th Street and University Avenue [in Gainesville, Florida]. We changed the name from WomenBooks to Amelia’s Bookstore, named after Amelia Earhart.

They bought that old building. Bonnie Coates’s name was on the title, and all the Women Unlimited businesses moved into it. We rented it from Bonnie Coates back then for $600 a month.

Around 1978 or 1979, Bonnie Coates went to the West Coast, and at some point, Linda Bassham followed her. Rosalie dropped out to finish her doctorate degree, and she had left. I can’t remember quite how that worked out when they were done and they wanted to sell it. Carol Aubin and I bought it, and we had a quiet partner who helped. We bought it from Linda and Bonnie at 18% interest in those days. Can you imagine that?

We made some changes. I was still working at Santa Fe Community College [in Gainesville, Florida] in the nursing program, and bringing feminism into that curriculum. Carol ran the bookstore. It was hard. We couldn’t sell many books at that time. We decided to sell textbooks for the women’s courses at the university, and that worked. That’s what kept our business alive.

Also, some women were wonderful. The local women were wonderful. They would come into the store, and they would hand us a big check, like $500.00. They helped us out a lot. It was things like that from the local women – and I adore them still today – who really saved our butt for a long time.

BE: Most feminist bookstores also organized community events. Was Amelia’s Bookstore involved in that? Did you have social and political events at the bookstore?

GG: As far as I was concerned, it was all political stuff. Though much of it was political, we did have dances and things like that at the Unitarian Universalist Church and other places. The social things were mostly dances.

Then we decided to have the Wine Down. That’s when it became a truly social place for people to come. If they bought something [a book or even a bumper sticker] they could get a glass of wine. Women would be outside and in the back of the building. We built that fence out back, with an all-concrete base to make an area for us to party.

The bookstore was a focal point. The newsletter was, too. Mostly, lesbians heard about dances and events through the UU church, and through the lesbians who came to Wine Down, which was always packed full.

We would meet to plan a march. We marched on the university campus over sports, over rape, and over whatever. Some professors might not do something we liked. We did a lot of things, like the second ERA parade in Tallahassee, and some Take Back the Night marches. There was always something going on.

BE: How long did you have the bookstore?

GG: We had that bookstore until 1982. It was my 50th birthday, I believe, when we closed it.

That was the end of the first feminist bookstore. Interestingly, in 1992, Cary Godwin and Susan Keel found the building where the second feminist bookstore, Wild Iris Books, was to be. It was a building that was right next door to where Amelia’s Bookstore had been.

BE: What was the atmosphere in Gainesville, Florida at that time?

GG: A lot had changed in those years between 1974 and 1982. By the 1980s, lots of social events were going on, like sports. I wasn’t involved in sports, yet we did have a softball team for Amelia’s Bookstore. That was a big deal. It was something I liked, and I’d go to all the games. You know, I did play. I wasn’t on an official team, but I played socially. That’s a good memory. We’d all go out to Bonnie’s place and play softball. We had the OWL’s basketball team, the Older Wiser Lesbians; and we’d play out at Sunland. And we had a volleyball team. We played volleyball out at Sunland, too. Yes, the Older Wiser Lesbians was definitely for anybody over 40. When we played volleyball, we would have so much fun. There were probably four volleyball teams and several basketball teams that we’d play. None of us knew what we were doing. We had a wonderful time.

BE: Tell me more about these sports teams.

GG: Other dyke groups got teams together. The softball was arranged by the City Recreation Department. There were a lot of teams plus Amelia’s Bookstore team. Softball, basketball, and volleyball were often simply put together by women who liked to play.

Lavender Menace came after that in 1991. It was organized by women who wanted to play sports together. They wanted to make the rule that all women could play regardless of their ability. They mixed each team with good and not-so-good players, and everyone could be a part of it if they wanted. This was after Amelia’s Bookstore had closed and the younger folks came along when Lavender Menace began. They did a lot of things. They would have walks, they would bike, or they would play. They had a softball team, again a part of the City Recreation Department. Rosalie and I wrote a grant for something about that to get money for the teams.

BE: Did the City Recreation Department know that any of the teams were lesbians?

GG: If they did know, they never said anything. Half of the people that were out there were dykes for sure. It must have been pretty much OK with the city. It was not a problem at all since we had to pay to be in the league.

We used to talk a lot and have meetings about the politics of softball, about how it was a working-class sport. We also had a lot of talks about Black women in softball. And Judith Brown had some good points about Black women at that stage, feeling so different, and so not-valued. We would spend hours talking about those things, hours and hours. Two of the things that we dealt with in those days: classism and racism in the lesbian community.

BE: Was there a lot of music that came to Gainesville?

GG: There was music and comedy that came to the MCC, the Metropolitan Community Church, you know, the gay church. We had a lot of women come, like Lea DeLaria. I think that was in the 1990s. And Suede. Yes, Suede came. Oh, yes, one of the very first lesbian entertainers, Alix Dobkin, “Lavender Jane Loves Women.”

We went to the Pagoda a lot, too, in Saint Augustine [Florida]. That was another social thing. And a lot of women, a lot of the musicians went to the Pagoda, too, like Holly Near and Alix Dobkin. The Pagoda would get into their own political issues. And it was a really wonderful time, and it was a hard time, too… there was a lot of infighting. We were doing what we’d been taught to do, trying to undo that. I think we’ve moved beyond that.

You can look at what’s happening today in terms of social issues like the party that’s going to happen in a few days where we’re raising money for Ky to adopt her third child as a single lesbian. It’s not based on yelling about something. It’s based on love and compassion. And it seems like we’ve achieved that.

We did go through that bit of fussing at the end of the 1970s. A lot of drinking went on, and a lot of women didn’t like that. They would be on one side and the drinkers on the other. I think we handled that fairly well. It was a no-smoking space, too, you know? Those kinds of issues were all dealt with by the women in the community.

I think one of the turning points was the Peace Walk. Yes, that was incredible. I remember the ones that got put in jail at the anti-nuke [anti-nuclear plants and bombs] demonstration. That was political, and it also was social. It’s how it was then. We mixed it up.

Carol and I went to the jail to see them, and it was really something, a real hoot. They were just as cute as they could be behind those bars. Yes, the Peace Walk. I wasn’t involved in that, but I remember that a lot of the women who were would come in and give us checks at the store.

BE: Do you remember any kind of social thing when you first came to Florida?

GG: You mean when I was living in Okeechobee? No, I didn’t do anything then. Yes, I was in a relationship that was secret, and that was the extent of our social life. We knew nobody else. Nobody else. And well, if you want to give the world an enema, send it down to Okeechobee. It was the pits. It was awful.

BE: Did you go down to Miami or Fort Lauderdale?

GG: No, we didn’t go to Miami. I know Fort Lauderdale has come a long way. I didn’t know what was going on in Miami. I had no idea. I was so closeted. It was the same way when I left Texas. We had a few friends, sure. As we got older, we got into professional jobs. It wasn’t like we were going out and playing softball, and drinking ourselves silly, like when you do when you’re in your teens.

It was never much social stuff going on. I mean, in the 1950s, you couldn’t even wear shorts. Women could not wear shorts in public! We would put on Bermuda shorts – that’s what we called them in those days. We did stuff like that to be ornery. One time, we all went to downtown Dallas to see the movie, The Killing of Sister George.[2] We wore our brogans, leather jackets, and all that “dykey” stuff that we used to do. Brogans? You know, the shoes that are laced up like men’s shoes, brogans. And I got arrested, too. Anyway, Sister George has an awful, awful ending. It was a terrible movie. We were all so hungry for some mirror of some kind.

And books like The Well of Loneliness. I read that book, and I hid that book, I can’t tell you how many times. And finally, my stepmother found it. And she took it out and burned it. At the same time, she burned some jeans of mine. So, I left home. We did auction off a Well of Loneliness when we closed the bookstore. We had a big auction for people to buy the books, and we did auction off an old, old copy of that one.

BE: Is there anything else that you want to mention?

GG: I know the most important thing that I see women doing now, as opposed to then, is we’re not attacking each other as much as we were in those days. We’re much kinder to each other. It’s a good feeling. The social media, I think, helps a lot in that way. We had no way to contact each other in those days, not that we would because we were closeted. You know, because we were so afraid. When I think about lesbians being able to get married now, and what was going on in the 1950s with me and people like me, it’s like a miracle. It’s as if it’s almost not understandable. You know, 50, 60, 70 years ago is not very long. Oh, my, what a huge shift. Yes. Yes.

One more thing. The idea of the bookstore initially was not only having a bookstore for women to buy books. Just as important, it was a gathering place to bring women together, to get the word out about feminism. It was definitely for Carol and me a place for getting a lot of people together with our Wine Down parties and dances. Carol was very creative, and the main thing was to get people together to get them into the store. Yes, it helps to sell books. Even if they didn’t drink, they would be able to socialize with each other, and at least to look at the books. They’d bring in goodies to eat and we had a lot of really nice volunteers.

I don’t think we had a bulletin board about social events that were happening. I don’t remember any bulletin board. It was done by word of mouth. Who knows where the people came from, and Goddess, people would come in there that I had never seen before. Yes, word gets out. Yes, the word got out.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it has been edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

[1] CETA stands for Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (1973), a federal jobs program for low-income and long-term, unemployed people.

[2] The Killing of Sister George (1968) was about a character in a British soap opera, who was a district nurse named Sister George, who was to be killed off in the TV show. The actor who plays Sister George loses both her job and her woman lover.