Jan Gibson, Cofounder of Lesbian Band, Moral Hazard

Interview by Lorraine Fontana at Jan Gibson’s home in Atlanta on November 20, 2024

Lorraine Fontana (LF): Where did you grow up, and what was your family like? Also, I like what you say when people ask how to spell your name.

Jan Gibson (JG): Gibson, like the refrigerator. [Laughter] I was born in Abilene, Texas. I was four years old when my mom and my dad divorced. My dad worked on oil rigs back then, and my mom was not given full custody of us. We had to live with his mother (my grandmother) for six years. My dad remarried briefly, three months after his divorce, and only my older sister and I went to live with him.

When I was in the first grade, we came out of school and our bicycles were gone. We had ridden our little bikes to school that day. We went back in to tell the teachers. But our teachers and people in the school said, “Oh, no. Nobody stole your bikes. You just didn’t ride them today. You forgot.” And we looked at each other and said, “I don’t think so.”

We walked home, and everything was gone in our house. My stepmother had left during the day. She had taken our bicycles from the school, she loaded up a trailer, and she was gone. I had a couple of coke bottles hidden, and we took those coke bottles to the store where they gave us a dime. We used the dime to call my grandmother, and she came to get us. We never saw that stepmother again. And we found out that my dad wasn’t even legally married to her because she had used a fake name the whole time. That’s why we lived with my grandmother until I was ten.

My dad had married a woman who was nineteen. My older sister was twelve, my brother was fourteen, and we were shocked. We thought, “Oh, my god, you are marrying a teenager!” Just me and my two sisters went and lived with him, and we began moving around.

Biographical Note

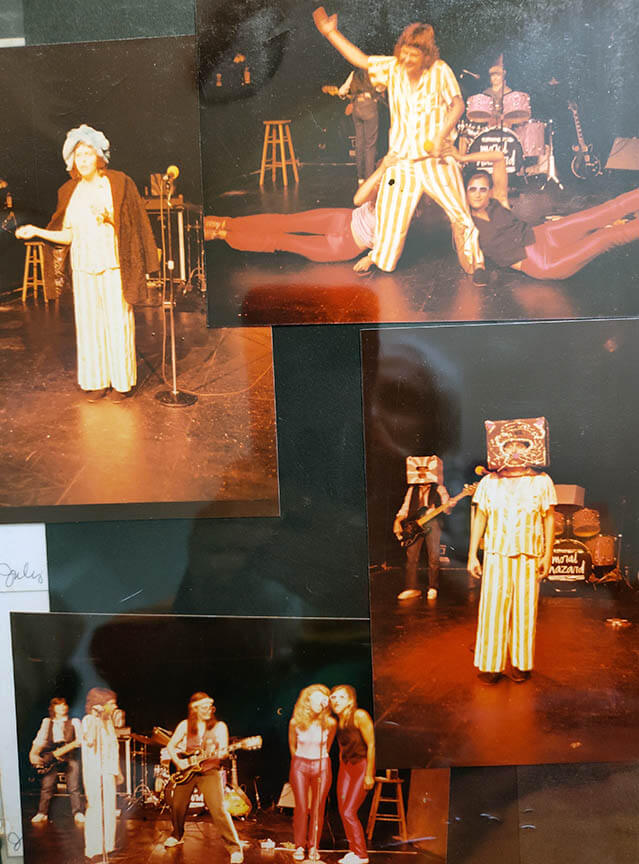

Jan Gibson, together with KC Wildmoon, formed the band Moral Hazard in 1979. The band made its debut with their “Moral Hazard Flight 101” show at Atlanta’s 7 Stages Theatre.

Moral Hazard went on to perform two more stage shows and numerous music performances. They made one CD with ten of their songs on it.

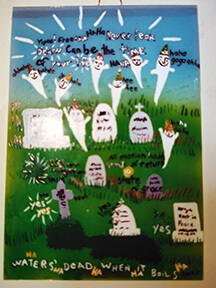

Along with writing most of the lyrics and music for the band, Jan Gibson was an artist through and through. Jan created art and furniture with natural objects. She enjoyed painting on these natural objects as well. She continued to write poetry throughout her life.

We moved to Lake Charles, Louisiana. We moved to San Antonio, Texas; and one summer, we lived with an aunt in Houston, Texas. Then we moved to Raleigh, North Carolina. We moved to Charlotte [North Carolina], and then we moved to Atlanta, Georgia when I was in the ninth grade.

By the tenth grade, I started paying attention in school.

I had started writing poetry when I was about ten, and I always wrote poetry.

We had started skipping school because we were so sick of being new kids. When we arrived in Atlanta, they had to count the days [we had skipped school]. All four of us were going to be held back because we had skipped school too much. We learned how many days we could actually skip not to be held back. In Atlanta, we skipped school together, all four of us, to go to the river. One day, my grandfather died and my stepmother came to school to get us out, and none of us were there. We got caught, but we still didn’t quit skipping. We just got more careful. We actually went to an office supply store and bought an “Out of Order” sign, and we would put it on the handle of a phone booth. This was when they still had phone booths and pay phones. We called our house when nobody was home, and it would keep ringing all day. That way, if the school called, it would give them a busy signal, and they couldn’t get through. That’s one way not to get caught.

We were innovative. By the tenth grade, I started paying attention in school. I had started writing poetry when I was about ten, and I always wrote poetry. I wrote really funny poems. I have some of them, and they really crack me up. When I was ten, I wrote a poem about children. I talked like someone older than ten, like someone who knew stuff. You know, quicksand was a really big thing when we were young. I would write stories about sinking in quicksand, which was probably a metaphor for my home life.

While we were in Atlanta, my parents decided to move again. I was only about a month into my senior year, and I stayed here [in Atlanta]. They moved back to Charlotte [North Carolina]. Initially my sister stayed here, too, until she and her husband moved to Charlotte. But I stayed here, and I ended up finding out about ALFA [Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance] right after I had graduated high school in 1972.

Finding Lesbians

LF: That was the year ALFA started, in 1972.

JG: It was 1973 or ‘74 when I came to ALFA. I came for a poetry workshop. That was when I met Elizabeth K. I had sprained my ankle crossing the street. I was so nervous because I had never known any lesbians. I fell and sprained my ankle crossing the street to get to the ALFA house. In the course of sitting there for the poetry group, my ankle had become swollen. When it was over, I really had a hard time. I had to hop to my car. I went to Grady Hospital the next day where they gave me one crutch. I saw Elizabeth in the library the next day. She told me that she didn’t remember me having a broken foot, and I said, “I actually did it crossing the street to come to ALFA.” That was my introduction to ALFA and the ALFA poetry group.

I knew I was gay or lesbian, but I just hadn’t ever been around any groups. I couldn’t believe it that I just looked up the word lesbian in the phone book, and that’s how I found ALFA.

LF: Did you already know that you were a lesbian?

JG: I had known that for many years. In high school, there were a couple of people that weren’t exactly “out,” but who were definitely gay or lesbian. There was a boy I really loved who was gay, and he ended up dying of AIDS. Anyway, I knew I was gay or lesbian, but I just hadn’t ever been around any groups. I couldn’t believe it that I just looked up the word lesbian in the phone book, and that’s how I found ALFA.

West Texas Feminist Living in the South

LF: I’m glad we used the word lesbian in our name. Obviously, you grew up in the South. Do you consider yourself a Southerner?

JG: I don’t, really. I think that so much of the landscape of our makeup is more, I consider myself more West Texan because that flat, dry land and those little mirages in the distance when it was hot all made a great impression on me. I was very, very lucky because my stepmother’s family was dirt poor. I mean, they were so poor that in the 1970s, they didn’t even have running water. But they owned 356 acres on the Red River, and I could find fossils.

I found tons of fossils there, and I loved it. When we moved, my father would not let me bring my fossils. He said, “I’m not paying to move rocks!” And I said, “These are not rocks. These are millions of years old. This is a sea creature from when this was a shallow ocean.” And he said, “I’m not moving rocks.” I think he lied to me. He said we had an uncle that was a preacher who taught at some Bible seminary or something. And my dad said, “Well, I’m going to donate them to your uncle RJ’s college, to their natural history museum there. And I later thought about it. I bet they don’t have a natural history museum in the seminary. I think he lied to me to make me think he wasn’t going to throw them away; but I think he threw them away. Sad.

I attended tons of ERA marches, and various “rights” marches. I did definitely consider myself a feminist and a lesbian feminist. But my focus was more on writing, on poetry.

LF: You don’t see Texas as in the South, and you don’t identify as a Southerner in that way. But do you identify with other terminology like feminist, lesbian feminist, activist, and artist.

JG: Definitely, but my activism was more like this: I attended tons of ERA [Equal Rights Amendment] marches, and various “rights” marches. I did definitely consider myself a feminist and a lesbian feminist. But my focus was more on writing, on poetry. I was proud to be part of ALFA. There were some women in the Atlanta area who were like upper middle-class women, lesbians, and they made fun of ALFA. They had a negative view of it. I always felt compelled to take up for ALFA, and say, “You’re just saying that because you’re not working class, and you don’t understand something essential about being a feminist.” I encountered some people that were talking bad about ALFA.

LF: Do you have a sense why they were negative about ALFA [Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance]?

JG: I don’t know. I think it was because ALFA didn’t have a whole lot of career women. We weren’t in ALFA because of our careers. We were there because of our politics. I don’t know for sure what it was. I do know that I’ve encountered that among some women here in Atlanta. They tended to be—I hate to say it—a therapist.

The therapist explained to me that he thought he could determine what made me a lesbian and he could change that. I said, “Do you know how ridiculous that is? I mean, really and truly?”

A Broken Heart

LF: Women professionals. And you came out at a fairly young age. Were you active in the feminist movement then?

JG: I was already out. I just didn’t have anybody to be out to. But my stepmother knew, and she tried to make me go to this conversion behavioral therapist. After the first two sessions, I got out of the car and thought, “I am not doing this!” I got out of the car, walked through the building, went out the back door, and walked back home. She would say, “I have to pay for that session.” I would say, “Well, I’m not going. I am not going.” The therapist explained to me that he thought he could determine what made me a lesbian and he could change that. I said, “Do you know how ridiculous that is? I mean, really and truly?” He couldn’t have any way to know that. He did change something, but what he would change was my heart. He broke my heart telling me that I wasn’t good.

LF: I didn’t know this, that that had happened to you. Wow!

JG: My stepmom gave up and said, “Don’t ever say anything to your father, or he will disown you.” That made it even easier to stay here when they moved away.

LF: Tell me more about what you remember about other parts of the community or any of the things that ALFA was doing, for example, around the ERA.

JG: I played music, practicing by myself, just with my guitar. I did perform in lots of ERA benefits. I don’t know if you were there, at the Georgian Terrace luxury hotel when there was that ERA benefit in the ballroom.

A bunch of women who weren’t even touching him were scaring him out of the hotel.

It really made an impact on me. It was non-violent and non-aggressive.

LF: I very well could have been. I don’t remember.

JG: What made the Georgian Terrace Hotel gig unique was that in the bathroom, we discovered a man was in one of the stalls masturbating. A whole group of us women got him out of that stall, and we escorted him to the street! We weren’t pushing him. We were jostling him out and parading him. I could see he was slightly scared because there were so many of us and one of him. I remember thinking that this was really a different scenario than I’ve ever experienced in my life. A bunch of women who weren’t even touching him were scaring him out of the hotel. What he was doing was illegal and disgusting. Gross. It really made an impact on me. It was non-violent and non-aggressive, but it seemed aggressive just in the numbers and just—not pushing him with your hands, just pushing him with your presence, you know? He was so nervous and scared that he tripped going up the stairs, and I thought, “Uh-oh, don’t start kicking him.” [Laughter] But nobody did.

LF: It didn’t get violent. That’s a great story. And at the Georgian Terrace luxury hotel. I can’t imagine that.

JG: I used to always have to go to the bathroom a million times before I performed. I don’t know what it was about. I did have kidney disease when I was young. I had it for a number of years and I finally outgrew it. The band used to make fun of me because I got to where I could pee in a beer bottle if I had to.

Turning Poetry into Song

LF: You always wrote from when you were a kid. And the poetry, of course, became songs when you started music. When did you start playing music?

JG: It was when I was in high school. The first song I played was about hippies on Tenth Street, called “Children of the Island.” And it was hokey. It went, “Children of the Island, pray tell where did we meet? On a crowded downtown Atlanta Street.” I was very drawn to hippies because I really loved the idea of the freedom they represented. I wasn’t ever into free love, and I was never promiscuous in terms of lots of partners, or casual sex. One hippy hangout was the strip on Tenth Street. Twelfth Gate Club, and the Great Speckled Bird, and so forth. People hearing this might not know what we’re talking about if they’re not in Atlanta. [The Great Speckled Bird was an alternative weekly newspaper in Atlanta, 1968-76 and 1988-90.]

My stepmother would say, “Who do you think you are, the Queen of Sheba?”

And I would say, “Yes! Yes, I am!”

Moral Hazard and the Queen of Sheba

LF: Tell us about your band, Moral Hazard, how that came about.

JG: KC Wildmoon and I performed in a show called “Other Harmonies: It may not be peace we’re looking for. There are other harmonies.” It was directed by a remarkable woman named Grace Zabriskie, or Grace MacEachron back then. She later went to Hollywood. She was in that movie with Sally Field, Norma Rae, about union organizing, and she was in lots of stuff. That’s how KC and I met.

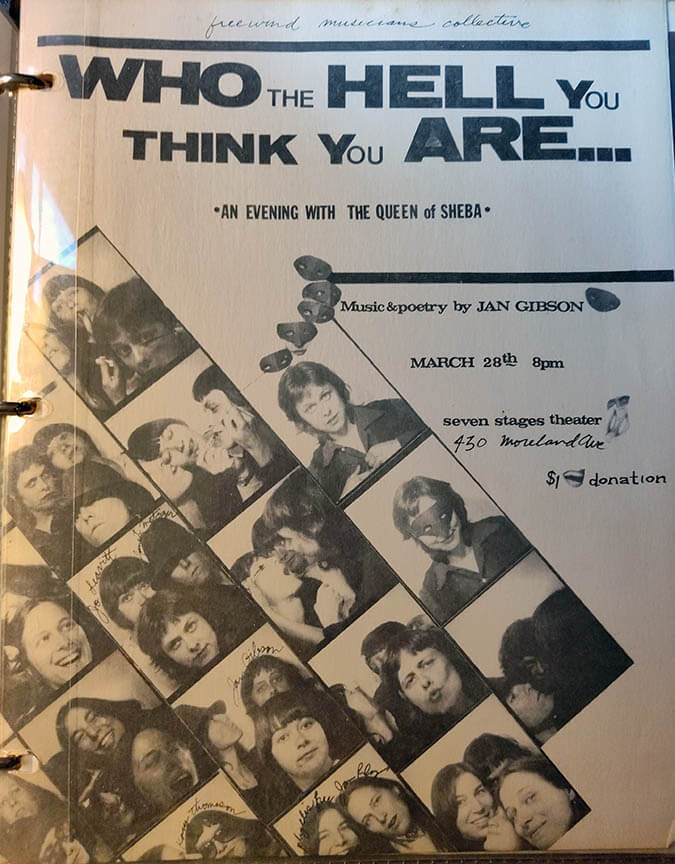

After that, I did that show at 7 Stages Theatre, “Who the Hell Do You Think You Are? An Evening with the Queen of Sheba.” That came out of something that my stepmother always used to say whenever I did stuff that was against what she thought. She would say, “Who do you think you are, the Queen of Sheba?” And I would say, “Yes! Yes, I am!”

But anyway, KC and I met, and we did “Other Harmonies.” We were thinking about doing something else. We were at a café, and it was at night. I think it was an election day. We had gone there to watch the election results when Reagan got elected. It was 1980, and I always saw Reagan’s name as “Raygun,” as in a ray gun.

We decided we needed to do a band with political and social commentary. When we set out to do that, we were actually in Debby C.’s kitchen with Libby H. and Jan R. We started writing “Bomb Shelter.” We looked in dictionaries for ideas to find the name for the band, and Libby found “moral hazard,” the insurance term. It means people who are very high risk. As soon as she said it, we all said, “That’s it!” Jan R. contributed a phrase or a few words to the song, “Bomb Shelter,” but we always credited her even though we had long forgotten what she actually contributed. That was the beginning of the band Moral Hazard. We decided to find a drummer and a bass player.

We probably knew Jaen Black, the drummer, and JB Sapp, the bass player. They had both just started playing their instruments. KC Wildmoon had more musical ability, and her ability to play guitar far exceeded mine. I really used my guitar like a rhythm instrument. To me, my guitar was just to accompany my poetry. I didn’t set my sights on being a great guitar player. At some point, I realized I would be lucky if I were kind of a good guitar player. At least I had some songs.

Interactive Performance

LF: What are the full names of the lesbians in the band?

JG: JB Sapp was the bass player, Jaen Black was the drummer, and KC Wildmoon was the lead guitar player. I played rhythm guitar only on a few songs. I sang lead on all of the songs, and I wrote the lyrics of everything we did. I wrote music and lyrics for a lot of what we did. We started practicing at JB’s house, and it wasn’t long until we did our first show, which was called “Flight 101.” It was a real success. People really liked it.

In fact, it garnered the attention of Dell Hamilton, the manager of 7 Stages Theatre in Little Five Points here. Dell talked about it in an article he wrote for the Atlanta art newspapers about the poet as playwright, and about how what we created was really unique because our audience knew us, and our audience would say things to us while we were on stage. Sometimes, people would come back when we would do two weekends in a row, Friday and Saturday nights. They would come back, and they would steal the punch lines! They would yell out the punch lines from the audience. I thought that was really funny.

LF: The theatre, 7 Stages, was in the Little Five Points area in Atlanta, near where the first and second ALFA Houses were located. Little Five Points was also where a lot of queer folks lived then, when it was still fairly cheap to live there. Tell me about the early performances of Moral Hazard.

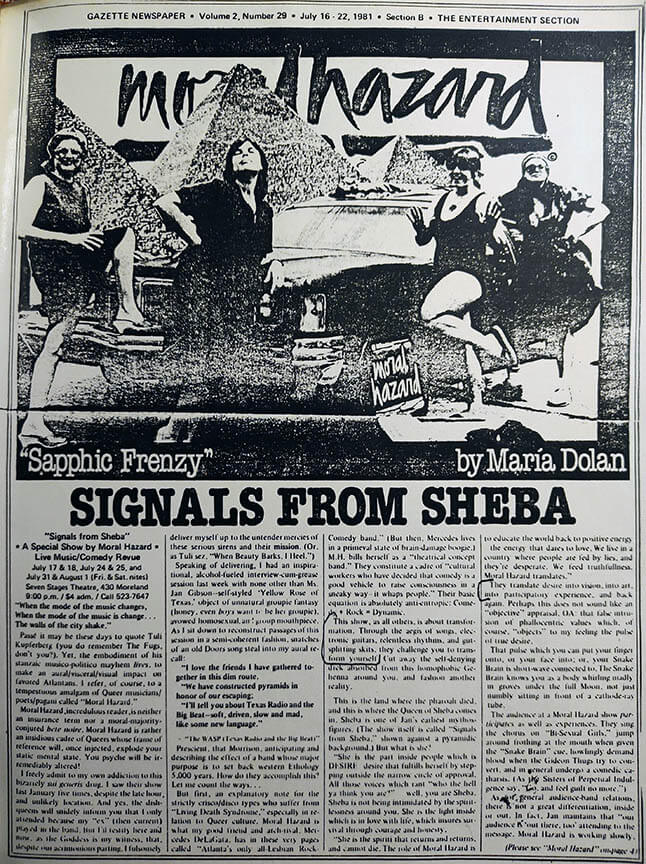

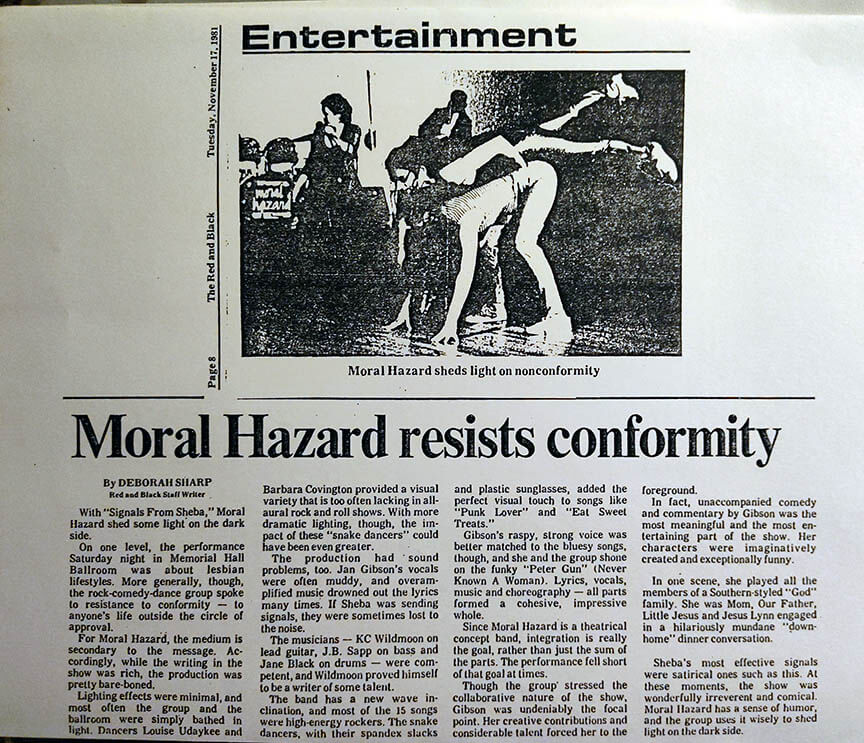

JG: The shows we did at 7 Stages were really successful and really fun. The second show we did, which was within that year of our first, was called “Signals from Sheba.” Again, it was really successful. We did a midnight show. I really didn’t expect that many people to stay up for such a late show, but they did. We also went to the University of Georgia in Athens and did a show there. We did a show in Tallahassee, Florida.

Maria Helena Dolan wrote some of the best reviews of Moral Hazard ever. She wrote, “Lock up the women and children!” [Laughter] Do you want to read part of it? Maria Helena was writing for The Voice and other independent newspapers that reported on arts and culture in Atlanta.

LF: How did you divide the responsibilities in Moral Hazard?

JG: Not so much. I developed a relationship with 7 Stages. When I approached them initially, they had a Shakespearean play scheduled, and they really didn’t have space. I asked if we could do a midnight show, and give the theatre the money from tickets at the door. It’s funny that at first, some of the people in the Shakespeare play were a little snobby toward us. They stayed after their play to watch us, and they became fans. The manager, Dell, and his wife, Fay, became our friends.

The Decline

LF: How long did the group stay together and perform?

JG: Let me see. Jaen left after the second show, which probably would have been 1983 or maybe 1984. We did do one more show that wasn’t really a Moral Hazard show. It was billed as a Moral Hazard show, but it was actually more of a Barbara show, which she called “Gaga,” the name of a performance artist. Barbara was my girlfriend at the time. I hated the show.

I found out I really don’t like performance art. Also, I was really embarrassed by the show. I don’t know if you’ve ever had this experience where somebody has recently come out as a lesbian. But when they talk, you begin to realize that they have so much unfinished business with men that they’re not likely to stay being a lesbian. Their emotional focus is still on men. That’s how she seemed, and I was very embarrassed. We members of Moral Hazard didn’t make fun of straight people, and we didn’t make fun of men.

In her show, “Gaga,” Barbara had a group of women wearing face masks. All the masks were the same. She called it the “face swarm.” I tried to talk to her because she seemed to show that there’s a bunch of people out there that are exactly alike, but she was not. She was not one of them. And there’s this other group of people that are real. I said, “You know, I don’t agree with that.” She would just blow up at me and go crazy. She also had this shadow thing where she was talking about men, and she was saying, “You’ve got to find a good man.” She was boxing into the air, making it look like hitting balls, that she was boxing men’s balls. I thought that this wasn’t a Moral Hazard show at all. I mean, my name was on it, and Moral Hazard is playing the music. But this wasn’t a Moral Hazard show at all.

“Do you think women are just attacked on public streets? They’re attacked in private institutions.

Mental institutions are a really big, good fishing ground for a predator.”

LF: Where was that performed?

JG: We did that one at Nexus. And I didn’t like it. And she didn’t like me for saying I didn’t like it. After that, I just felt like I couldn’t be trusted with my own integrity, having let this girlfriend embarrass me artistically.

A Dangerous Diagnosis

Also, it’s one of the side effects of being diagnosed as bipolar. I was only thirty, and it was really hard for me to believe that I was a person who fit the criteria. But I couldn’t deny that I had been kind of psychotic. The kind of psychosis was like I couldn’t tell if it was day or night–if it was overcast, I’d be thinking, hmm. And it was all very interesting in a weird way. It destroyed my sense of confidence for a long time because nobody believed me.

When somebody tried to rape me at the Georgia Mental Health Institute, my feminist friends said, “Your psychiatrist said all women say that in there.” I said, “Do you think women are just attacked on public streets? You don’t understand that they’re attacked in private institutions. Mental institutions are a really big, good fishing ground for a predator.”

I was really angry, and I attributed it to people’s class divisions. I thought I was surrounded by women who had professional careers, but who didn’t know how dangerous it is to be in a mental institution. They didn’t know that we don’t have any power, and nobody believes us when we try to talk about it. It just really impacted my ability to talk about things. I started painting. For a long time, I didn’t want to engage with people who were going to tell me that I was lying or trying to create drama. If I want to create drama, I’ll do a show. I’m just not that person.

LF: When you got diagnosed, and when this was happening, where was it in relation to the history of Moral Hazard?

JG: It was after the show “Gaga,” and I was still with Barbara. The band was still practicing, but Jaen had left. Jaen got mad and left.

LF: Was there another drummer at that point?

JG: Yes, but it was somebody that none of us knew, and she didn’t engage with any of us. We missed Jaen a lot. I could not hand over what had been many years of work to this new drummer just because she was pissed off, or because she wanted more attention. I said to this new drummer, “Just bring me some comedy. You’re so funny.” I thought, just to appease her, I have to start writing for her? That’s what I was doing. I had started writing for them all.

When I Look Out and See Your Faces, I See Light

LF: With Moral Hazard, beside singing some songs, what other stuff was happening during a performance?

JG: I would always start with a monologue about the audience, and say, “When I look out and see your faces, I see light. It’s the same light that you see in the texture of leaves. It’s the same light that comes from the sky and comes up from the ground. It’s the light that’s on the water. It’s the light that’s in your eyes.” I talked about how this light probably, I believe, generated the first word. And I said, “We’re going to generate words for you tonight.”

And then the song would be a soft song, with words like this: “I was born a survivor, a survivor I will long be / because I’ve learned the kind of love that sets love free.” It was about acknowledging people’s spirituality. That would always open the show. Then, I would say something like, “Now we’re going to get a little zany!” That was the part that I considered liberal values of inclusiveness and diversity.

Black, a University of Georgia newsletter, 1981.

Sometimes, after the monologue, the show opened with a routine about this man and this woman, Harold and Maxine. The husband convinces the woman to go to a gay bar. He flirts with a guy. At first, you think the woman’s going to be upset. But when another woman comes over to introduce herself, the tag line was, “Oh, hi. I’m Max.” She had already dropped the end of her name and became “Max.” It made me think of Niki and Stewart, friends who both turned out to be gay. And that’s kind of what I was writing. I used things I knew and people I knew.

Also, I would do this comedy thing, probably not very politically correct. I would say, “Last night, my spiritual advisor, Ricky Ricardo, appeared to me, and he said, ‘Jan, I have to tell you something.’ I said, ‘What is it, Ricky?’ He said, ‘Well, you know, God appears to me, and he tells me things he doesn’t tell anybody else. He appears to everybody else, and he tells them things he doesn’t tell me. Last night, God appeared to me. In this little, teeny voice he said, ‘Ricky, I have to confess.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about? You’re God. You don’t confess to me. I’m Ricky Ricardo.’ He said, ‘No, I have to confess. You have to tell them.’ I said, ‘Tell them what?’ He said, ‘I didn’t write that book. You know, that book everybody thinks I wrote? I didn’t write it.’ Ricky says, ‘No, no, no! I’m not telling them. Are you trying to make a mother out of me? I mean, a martyr out of me?’ And God says, “Ah ha ha! I made a fodder out of you.’ ”

It was a silly pun, but it’s also kind of effective. “I didn’t write that book! You have to tell them because everybody’s really fucking up, and they’re blaming me.”

LF: The shows could be all kinds of elements, including not only musical and topical political music, but also skits and comedy.

JG: It was a real mixture of whatever was coming out of my mind. Abortion was a topic back then, as it is now. It was a little off the wall, but I thought it was really funny, about how evangelistic maintenance people go into clubs and restaurants after hours and pull the used tampons out of those boxes because they have to give them proper Christian burials, thinking those are eggs. Stuff like that, which might gross you out, but you think, “Oh, my god! I could see that happening eventually.”

It’s very frightening to think of women being left to die because doctors are afraid to treat them.

LF: Like where we are today, politically?

JG: I’ll tell you what really scares me. My daughter wants to get pregnant. She’s thirty-four, and I’m afraid that she might miscarry. It’s very frightening to think of women being left to die because doctors are afraid to treat them.

It’s gross. it’s criminal. I can’t believe we’re still dealing with it. We’ve gone backwards. We know what’s happening. They want to take us back. We say we’re not going back, but it’s not easy to maintain.

Endings and Struggles

LF: What started happening that ended Moral Hazard?

JG: Really and truly, part of it was that I was in a bad situation. My girlfriend, Barbara, did things like this: We were playing at this club off Tenth Street. When we were just about to take the stage, after setting up equipment, she would ask, “Where’s my microphone?” Everybody looked at each other and said, “I don’t know. It’s your microphone.” She said, “Nobody set up my microphone.” And she just threw a fit. She said, “It’s either me or them, Jan. Right now.”

Well, I’m sorry, but I lived in a house that I shared with her that I couldn’t afford without her in it. I wasn’t prepared to move on a dime to get away from her. But I also didn’t want to get away from the band members. It was ridiculous. That’s the kind of thing Barbara did. She was mean and rude to Janet M. because Janet asked specifics about the show “Gaga.” Barbara acted like that was an insult. I remember thinking over and over, “This person [Barbara] doesn’t share my values. But she shares my house.” It was Linda B.’s old house that we were renting.

It would overwhelm me because I knew I couldn’t afford to live on my own. I can’t tell you how many times I was just left bereft when Chris R. moved to California, and I couldn’t afford the house we rented on Sterling Street together. When she left, I had nowhere to go, nowhere to live. It was just a shock. I had done everything I could to help her. When she left, I realized I had not helped myself, and I had nowhere to live.

I wasn’t ever homeless, exactly. At that point I didn’t have a car, and I drove a van for a little school where I picked up developmentally disabled kids to take them to their place. I ended up living in this little back room for maybe a week. It wasn’t even a room. It was the back porch of Debby C.’s house. There was this little loft with no way to get up into it. I can’t remember what I did with my dog when I had to go to work. You know, my dog Rodeo. When I was hospitalized, he was with me at Linda B.’s. Rodeo would break out and go to every place in Little Five Points and Candler Park that I had lived, to try to find me. It just so happened that there were people that knew him who moved in after I left. But they finally put my truck in the back of Linda’s yard and let him live in it. I was gone for about three weeks or so.

I had worked at Grady Hospital in the psychiatric unit when they introduced patient advocacy laws. That’s how I knew how to get myself out. I got myself out of Georgia Mental Health Institute. I wasn’t really organized yet. I ended up going to stay with my parents, which was a huge mistake. They took me to a Christian practitioner to make sure I wasn’t possessed by a demon. Can you imagine? I felt like, “Uh oh — I am now!”

When I came home, I was so drained. When I saw people that I dearly loved, like Linda B., and even Jaen, I would see their faces do something hard to describe, like a visual stutter. When I would see Jaen, I would think of her pointing at me and laughing. And Linda B., who’s such a sweetheart. Linda B. got annoyed with me because she signed on as my family representative at Georgia Mental Health Institute. I couldn’t leave unless she came to get me. She couldn’t come get me until later in the day even though I could have left first thing that morning. She didn’t understand how important it was to get myself out of there.

I had the weirdest things happen. People thought they knew me. One time with Moral Hazard, I used an empty brandy bottle and used it as a flask. It wasn’t empty. I put honey and lemon juice with tea in it, and people assumed I was swigging, actually drinking. But I wasn’t. When I was admitted to Georgia Mental Health Institute, Linda D., who worked there, told them that I was an alcoholic, and that I needed to be on the alcohol detox ward. I said, “I don’t drink.” I really don’t drink, but they didn’t believe me. They required friend after friend, Linda B. and Kay H. and so-and-so say, “Hey, she doesn’t drink. That was just lemon juice and honey and tea. It was a show, an act.”

LF: This is an interesting example of how women aren’t believed. In this case, if a woman is diagnosed with a mental illness, they assume she can’t be telling the truth if she’s mentally ill as if that’s part of her illness.

JG: It’s also so prevalent. Women are not being believed when they’re attacked. Or when there’s some guy claiming that it was consensual.

We Weren’t in it for the Money

LF: How much money did you make on the band gigs, and who bought all the equipment?

JG: Not very much. We would give the money people paid at the door as our “rent” to pay for the use of the theatre. We had our own equipment, and we didn’t have to rent equipment. In Athens, I’m pretty sure we were paid from some kind of a student grant. Also, we got a grant. Barbara got a grant in part for her show “Gaga.” But we never really made money doing it.

As for equipment, we had our own stuff. Jane P. did the lights, and another friend did the sound. Cherry Omega often did security. For a while, we rented the old Masonic Temple in Grant Park where we could have dances. We set up in the round, in the center to play, and it was kind of like a hullabaloo or something. It was really funny.

I sent her this stuff about that transition, and about how I believe that we all live inside love,

and that there’s no outside, ever. We just forget where we are.

We All Belonged There

LF: Tell me a story about your life recently.

JG: At the Masonic Temple, they had a concession stand to sell beer. Cherry Omega was our security person at the door down the steps. A few years ago, Cherry called me when she was dying. I was so sad. She said that she was scared. I felt really bad for her. I sent her this stuff about that transition, and about how I believe that we all live inside love, and that there’s no outside, ever. We just forget where we are.

Then, she died. I didn’t know if she had even gotten my letter. But I got a letter from Cherry’s caretaker in hospice, who said Cherry had gotten my letter! She said that Cherry had left me a thousand bucks! She had left me whatever the end of her account was. I was so glad that she did get my letter, and that it did help her. I was so relieved. I felt so bad when I heard she had died, worried that my letter didn’t get to her in time.

LF: What was the most memorable performance outside of Atlanta?

JG: None. The experience of being in our community, at 7 Stages Theatre, was the highlight. That was the best. To look out and see people beaming at us, people who had known us for years. They were so surprised that we were doing that, that it was just a real feeling of being embraced by your community, and of us embracing them. It was really phenomenal. That’s one of the things that Dell, the manager of 7 Stages, wrote about in the art section of the newspapers, how there was an immediacy between us as the performers and the audience. They were seated in a community and we all belonged there. That was just the very best, being home with everybody.

The Eye of an Artist

When Catherine was maybe nine years old, we used to practice at Kay B,’s basement. Kay would play drums, JB played bass, KC played guitar, and I sang. But we weren’t working toward anything. I had lost the desire to put myself in front of people in a certain kind of way. I wasn’t doing poetry readings anymore. The only thing I did was paint. I started painting and doing once-a-year art sales at the First Existentialist Congregation of Atlanta in Candler Park. I did that for a long time, and then I stopped doing that, too.

LF: Your life as an artist has been through many different mediums, clearly. Do you see yourself primarily as an artist in the world?

JG: I think so. Even when I’m not doing art, I have an artistic eye, I have an artistic ear for phrases and words. I’m addicted to writing on a typewriter or a keyboard because I can see it. But I don’t like writing by hand on a sheet of lined paper because I’ve never liked my handwriting. I’m left-handed, and I smear it up and it just doesn’t come out right.

Writing those stories really helped me re-seat myself in my “self.”

LF: Do you keep a journal?

JG: Yes, I do. I had an experience that really rocked my sense of belonging in the world. To remedy it, I sat down with several composition notebooks. I wrote story after story after story of things that really happened in my childhood. I realized that I’ve got a great sense of humor. Those stories really make me laugh. For some reason, even the ones that are kind of sad, I think they are funny. Writing those stories really helped me re-seat myself in my “self.”

Being Made a Pariah

I had experienced being made a kind of pariah by a bunch of women who were very grossly misinformed. I thought somebody was giving me land in Elijay, Georgia [near Atlanta] to build a little house. They swore up and down they were going to deed me the land. After I built the house, they charged me. They said after I’d been there for four years that I owed them thousands of dollars because they had decided that I was renting the land underneath my house. They also said that I was renting the house even though there wasn’t a house before I built it. They said that they could do whatever they wanted because they owned it. It was horrible.

When I came to Atlanta to try to find someplace to live, they also gave away my daughter’s horse. We never saw him again. And I had specifically said, “Do not do anything about Red until I get back up here. Don’t.”

It just blew my mind because what had happened was that this individual was a big liar, and I didn’t know it. She had turned to me one day and said, “Oh listen, I need you to tell Catherine not to say anything. Neither one of you can say anything about Doris being up here.” I said, “Well, I understand. Haven’t you broken up with Karen?” She said, “No, Karen can’t find out about Doris because Karen’s taking me to California. If she finds out, she might not take me.” I said, “So you’re stringing your partner along? Really? You’ve broken up with her, but she doesn’t know? And you’re stringing her along so she’ll pay for a trip to California?” She said, “Yes.” And I said, “Don’t involve me. Catherine is seven years old. I’m not going to tell her to lie for you. And I don’t want to lie, either. So just leave us out of those kinds of intrigue.”

I understood that she didn’t realize that it was abusive. Karen was really depressed. And she prolonged her depression by keeping her uninformed, and she was gaslighting her. Oh, my god, she hated me. She used me. She treated me like I was a bum, that I was bumming off of her, and I wasn’t. I mean, I even sent my daughter to camp. I bought a horse. I built that house. I spent $12,000 on her property. That was my life savings. It was just the most bizarre thing.

Back-up Band or the Main Thing?

LF: Do you miss Moral Hazard?

JG: I loved doing it, but when I listen to those songs now, I think, “We should not have played it like that.” A lot of times back then, I would tell them, “Y’all, don’t you hear how we sped up, slowed down, sped up, and slowed down the song? Could we just do it slower?” They had this idea that they were like kick-ass rock and rollers. I had this idea that slow, sweet music is just fine. I didn’t have any interest in being a kick-ass.

LF: How do you describe the kind of band Moral Hazard was?

JG: Musically, we were really a garage band. I mean that we weren’t that accomplished in terms of our musicianship. But I always saw Moral Hazard as a back-up band playing back-up music. The others saw Moral Hazard as the main thing. I understand that it was, in a way. But when we started it, I saw it as augmenting a show. It was Moral Hazard and comedy.

LF: Is there something about your life story that connects with your lesbian feminist part of your life?

JG: I wish that ALFA still existed. I wish that there was still a base of some kind. Linda B. would say, “Jan, I wish you’d come back into the community.” And I would say, “I can’t find it. I don’t even know where it is!” I mean, I can’t just go to Charis Books and More. When I say that I don’t know, that’s the only thing that exists as far as I know. As for women’s stuff and feminist stuff, there are organizations that are queer and that have women in them. I joined SONG [Southerners on New Ground] when I first got back to Atlanta, when I found out about them. I thought I could be in the Atlanta Women’s Chorus. But to tell you the truth, I don’t like to go places that much.

I mean that I don’t even like to go to the place wherever you would go to practice. For one thing, my little dog is thirteen, and I try to spend as much time with him as possible. I love him so much, and he’s been such a great companion for me. You know, if ALFA existed in its old location, that’s pretty close to me. I mean, you could just go to the ALFA house and hang out. You would run into people, and there was the poetry group.

Reading and Writing

LF: Did you ever go to Womonwrites?

JG: Yes, I think I went there two times, and I really liked it. But I’m not comfortable with people who might critique my stuff, or where I would critique other people’s stuff. I used to be in poetry groups a lot. At Callenwolde Fine Arts Center in Atlanta, I got to read with Rosemary Daniels, “Sleeping with Soldiers.” And I got to meet Adrienne Rich. At Callenwolde, that’s where I met Jimmy Starr. It turned out that he was Barbara’s husband back then. But I didn’t know her yet. I just knew him. He and I started the Awkward Unicorn, a poetry newsletter. And I started the readers series at the Great Southeast Music Hall, but very few people ever came to that in the early 1970s. That was way before there was Spoken Word Enthusiasm.

I wish I still had some copies of that newsletter. I used to laugh and say to Jimmy, “We’re just going to do what Ru Paul does.” That was back when Ru Paul wasn’t famous yet. We knew Ru Paul was going to be famous. Every time you got on a city bus, there were Ru Paul posters, flyers, and such. I said to Jimmy, “We’re just going to go around and put this poetry newsletter all over Atlanta. We’ll just set it down in places. And that’s what we did. Ru Paul did really get famous like that.

The best thing that ever happened to me was cutting the cord when

Catherine, our daughter, came out and was born.

The Joy of Being Nonnie

LF: Do you want to say anything else about your life?

JG: The best thing that ever happened to me was cutting the cord when Catherine, our daughter, came out and was born.

I think we were the first two women as a couple to have a baby there at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta. They had a thing called the “stork club” where the new parents could go and have a little dinner together. And when we went in there, and we were, of course, the only lesbian couple, everybody was like… it was so hilarious to us.

Catherine was born in 1990. And she and my partner Judy, had to stay for a couple of days. I was staying in the hospital with them. I would go up to the nurse’s station and say, “Is it okay if I take a shower?” They would say, “Oh, well, the showers are just for females.” They are for the mothers. I said, “Well, I’m a female.” But I didn’t give birth to the baby. They said, “I guess so, this once.” I’m like, “All right. I’m going to make a habit of it. I’m going to come here every day just to take a shower and to bug you.” It was so hilarious, it was so horrible, and it was so funny the day she was born.

LF: How is your daughter doing now?

JG: Catherine is married, and her husband, David, is a writer. She’s thirty-four. She just sent me David’s new book. This is his twenty-something novel. She went to Georgia Tech, and I’m so proud of her. She went there on a Hope scholarship, and she came out with zero debt. Zero! Because she also worked as a resident assistant for her dormitory. She worked her way through university, and she got a job immediately with some financial analyst. She’s brilliant and she makes a ton of money.

LF: She became one of those professionals.

JG: She did. But I’ll tell you, she’s so together. I’m really proud of her. And you know, she’s the sweetest. She says, “Nonnie.” She always called me Nonnie. She says, “Nonnie, you made my childhood. If I hadn’t had you, I wouldn’t have had anything. You gave me so much, and we had so much joy. And it was because of you.” And she tears up. She makes me cry when she talks like that.

My mom is ninety-two and she loves to read. She wants to read one of David’s books, but she has a lot of trouble seeing. She usually reads big print, and I’m going to have to go buy her one of those page magnifiers somewhere. I’ll have to whiz through it and send it to her. I have a Kindle that Catherine gave me, and it’s great. I can make the print as large as I want. But my mom doesn’t have a Kindle, and she really wants to read one of David’s books.

We Can Still Hear Your Voice

LF: Is there anything else that you want to say?

JG: I’ve been really disappointed that the band members haven’t stayed in touch with me. I was really disappointed when I heard that KC Wildmoon had posted our stuff on iTunes and Spotify. She didn’t let me know, and—I mean—it’s my stuff. It’s weird. I have offered many times over the years to get together and write more. I thought that we could write some songs just for fun, you know, not necessarily to write performance-quality songs.

LF: To hear Moral Hazard’s CD, Step over This Line, can people go to Spotify and iTunes?

JG: Yes, they can. They can hear our CD that we made, Step over This Line.

The names of the ten songs on that CD are:

“Take a Walk on the Dark Side”

“Lavender Jane Loves Money, She Works for IBM.”

“Bisexual Girls” is really funny. It says, “Hi, I’m Lisa. I’m bisexual in theory, but not in practice. / I mean, I am a part of the bisexual generation. / I’ve always just kind of assumed / I’d have a brief affair with a woman, / when I met the right woman.”

“We Don’t Make No Plans No More,” which is a really good rock song.

“Yellow Rose,” which is kind of sexy.

“Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.”

“Eat Sweet Treats,” which is a really simple, funny little song.

And “Meditation.” That’s a good song, too.

I don’t know about iTunes, but I know that Spotify does not credit the writers, like for lyrics or for the music. Spotify only uses the band’s name. Look there for Moral Hazard.

LF: We will not see your name, Jan Gibson, unfortunately, on Spotify. But we can hear your music. And we can hear your voice through this interview. Thank you so much for letting me come to interview you, and to find out more about you. I’m so happy to see you, dear. This is wonderful.

JG: Yes, it is wonderful. I’ve been happy to see you, too!