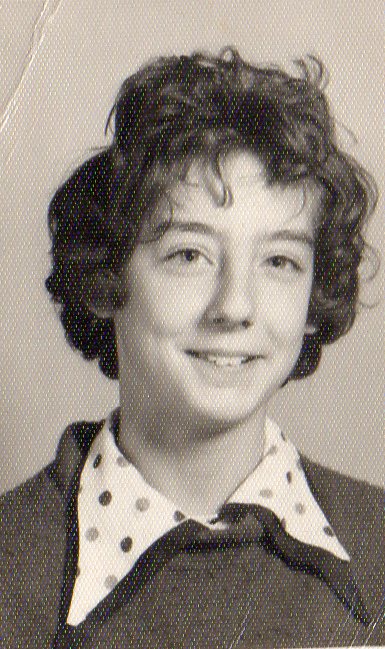

Drea Firewalker: Myte Dyke

- See biography

- Interview with Drea on YouTube

Merril Mushroom interviewed Drea Firewalker via Zoom on July 15, 2025. This interview preceded a joint interview with Firewalker’s wife B. Leaf Cronewrite aka Mary Ann Hopper. You may also view this interview on YouTube.

Biographical Summary

Drea Firewalker (Andrea Nedelsky) was “born lesbian” in 1951, the oldest child in a very poor, violent, abusive family. Her father came from a large, close-knit, male dominated Slavic family, while her mother was a young Southern belle. This was not a good combination. They lived just outside Chicago in a neighborhood of immigrants that was rigidly divided into ethnic groups. Drea’s paternal grandmother, whom she adored, was a psychic who encouraged that spiritual part of Drea to flower.

The family moved around, living with different relatives, until they finally settled into a small four-room house with wood heat and no plumbing. The children were rough, dirty, and frequently did not go to school. Drea’s mother managed to manipulate a situation with some relatives which allowed the family to move to a white, suburban neighborhood. There they were considered to be “white trash” since they carried their old behaviors with them – drinking, fighting, trashing their yard, and creating disturbances.

The poverty in which Drea lived contributed to her poor school attendance, and the suburban schools failed to educate her. She was so far behind that she was placed in special education throughout her high school years, and this turned out to be somewhat of a support group for her. While visiting homes of her more well-off classmates, she became acutely aware of the unfairness of economic differences.

In her teens, Drea had the opportunity to attend a Baptist summer camp, and there she met the woman – not a lesbian – who she would again, serendipitously, encounter years later and who, in both instances, would change Drea’s life. She became independent, finally learned to read and write, completed a college degree, went into the trades, became an activist, and in 1984, met Mary Ann, now known as Leaf. As Drea said, “Mary Ann (Leaf) brought the power of my lesbianism to front and center.”

Drea Firewalker: It’s been interesting getting ready for this interview. Mary Ann and I both had to step back and look at how we got to where we are today. We’ve been together forty plus years. Mary Ann’s first thirty years of navigating the world were based on traditional, normal social expectations. In my first thirty years, I didn’t have a clue of what normal in the world meant. When the two of us met in 1984, my world expanded to how much was going on in the womyn’s movement. I knew about the LGBT groups by attending MCC [Metropolitan Community Church]. I soon discovered how limited I had been with understanding the community outside of the church. Mary Ann brought the power of my lesbianism to front and center.

Slavic Family Background

The structure of my family was about the power my parents had over us children. I made it out of a very violent family that had totally destroyed my self-confidence and sense of self-worth. Back in the ‘60s, being queer brought a lot of physical and verbal abuse from my family, friends, and strangers. As a young person, I was always calculating how I should navigate through this world as a survivor of an incredibly dysfunctional family. My personal journey changed when I found PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays] in 1973. That gave me support for my identity. Instead of feeling like I had to hide who I knew I was, PFLAG helped give me my voice against those who would rather that I stay invisible or silent.

I always say, I know how the story of my life starts: I was born as a lesbian baby. I know how my life shall end: a dyke woman shall be laid to rest, satisfied that I had lived as a Mighty Dyke, the true Keeper of Lesbian Secrets.

I know how my life shall end: a dyke woman shall be laid to rest,

satisfied that I had lived as a Mighty Dyke, the true Keeper of Lesbian Secrets.

I was born March 7, 1951 in Joliet, Illinois. I grew up there just outside of the Chicago area, where the Slavs, Czechs, Poles and other Eastern European immigrants settled. The area runs between South Chicago all the way down to the border of Joliet, Illinois. In those ethnic groups, we always had an unspoken mistrust of outsiders. (There were still the leftover effects of the McCarthyism period.) The African Americans lived on one side of our neighborhoods. They definitely didn’t come across the street where our families lived. On the other side of the neighborhood lived the Native American Indians. The American Whites, what we called English-speaking, lived on the other side of the tracks which separated all of the ethnic groups from them. Conflict among groups was normal. Each group lacked trust of the other groups.

Those were my early years of growing up in an ethnic, Eastern European space. My grandfather owned the Slavic butcher store; my aunts ran the noodle shops and the bakeries. My uncles had gas stations right across from the Joliet prison. I used to hear all those wild stories about the prison. As a child, I pointed to the bullet holes in the walls. The mobsters were real, so I learned early to be cautious of strangers. That was kind of the neighborhood.

My immediate family ended up consisting of nine of us: me, six siblings, and my parents. My father, Andrew, believed that he was reincarnated as a western diehard, mean son of a bastard. He drank hard, spoke tough, and believed children weren’t to be heard. We lived very, very, very poor. Our home didn’t have very much electricity in the house. There was one line of power that fed the entire home. The well water was just outside the front door. When my dad put the well in, he decided to put a penny in the concrete for the years his children were born. That was about the closest I came to being acknowledged as his own.

My dad, who had been raised in this Slavic community, wanted to have that tough American image. He joined the Air Force and was stationed in Lake Texoma, Texas. (He was an only child, by the way, and he was finding his way out of his Slavic community.) That is where he met my mother, Mary Elaine White. He’s an Eastern European Slav raised with all of the ethnic traditions and the male machismo that comes with it. My mother was an Okie from Oklahoma. She was sixteen when she met my dad at the Air Force base.

My mother, a true Southern gal, would go over to the base to dance and meet the Air Force guys. That’s how my mother and father met. It wasn’t like it was romance. I think that my mother being so different from my father and my father being so different from my mother was the attraction for both of them. My dad was kind of suave, and my mom was very attractive with the Southern charm. The two of them were having a quick attraction affair. They knew nothing about each other’s lives. That would quickly change.

My dad got a call from his mother. His father, who worked at the steel mill, had had a terrible accident at work. He had burned over ninety percent of his body and was not expected to live. His mother called the service [the Air Force] to get him to fly immediately home. His father died a week later. That was in 1950, the end of the year. After his dad’s funeral, my dad went back to the Air Force, but my dad’s mother requested he be released after this tragedy to stay home because he was now the head of the family, and she needed him. Unfortunately for my father, he never had a say in getting out of the service, always a point of anger with him and his mother when he drank. He’d complain how she ruined his life.

PULL QUOTE

My father believed that he was reincarnated as a western diehard, mean son of a bastard.

He drank hard, spoke tough, and believed children weren’t to be heard.

Before my soon-to-be father was released from the service he had gone back to the Texas Air Force base where he learned my soon-to-be mother was pregnant with me. They decide to have a quick civil marriage. Soon he was released from the service and sent back home to his Slavic neighborhood where he carried back with him my mother, who had never lived outside of Oklahoma.

A little bit of my mother’s situation. My mother was the youngest of seven siblings. Her mother, Anna Mae, had passed away when she was twelve years old. My mother was raised by her older siblings.

My dad carried my mom back to this Slavic area, and pretty much plunked her down in a non-English-speaking, not-willing-to-get-to-know-you environment. I was born three months later. So, I say this baby lesbian was born in the middle of turmoil. I always felt like I was there during their tragedy of my dad losing his dad in such a tragic way, my grandmother learning about this southern woman that he’s carrying home. To top it off, my father discovered that my mother had already had a son at age fifteen. She had left that son with her oldest sister, Irene, an aunt who I later adored. I learned about the existence of my brother Terry much later.

So here I would be born into a family from two different cultures, young, and really unemployed, and the family conflicts were always erupting. All of my dad’s family liked to drink heavily, and my mother, who didn’t speak any foreign language, was often shut out of the conversations between families. She was always accusing him of “not wanting her to know what’s going on in the family.” And she was right. They didn’t. They were always badmouthing her about how she ruined my dad’s life.

I was thinking about how to present my Slavic relatives in this interview. Part of my family—the aunts and uncles and great-grampas—were entrepreneurial in their life. They were driven, and they loved being a family. But my dad had married outside the ethnic group. He married a woman who was a Protestant; he was a Russian Orthodox Catholic. He married a woman who already had a child. They didn’t get married in the Slavic church. Everything that caused problems in their early years began with these choices.

The other thing that I was aware of growing up as a child was there are stages. What did I know from zero to four or five? Probably not much, except feeling the turmoil of my parents’ lives.

My early years of instability would be caused by how many relatives our family moved in with before moving to the next one. They shared their homes in Illinois with us until the next argument that would send us to my mother’s family down south to Durant, Oklahoma. There we would live with one of her sisters, or one of the other relatives. My dad would follow and take jobs digging burial plots in Durant because he had to have work. My Grampa White, my mom’s father, would always say, “You’ve got to work!” He’d hammer at my dad until it was time to move back north to the Slavic side of the family. This went on for years. My mother would have us spend time with my half-brother, her son, who lived with Aunt Irene. I never really made the connection that he was my brother until I was seven years old.

I used to tell people that my mother was a Rebel who stood and cried during Dixie [a song, like an anthem for the Southern United States], and my dad was always fighting the Civil War because he wanted to be a real American, a true Yankee. My parents always had these differences hanging over them, and they didn’t fit in with either family. If I named my parent’s relationship, I would name it “The tragedy of love and hate of one another.”

Psychic and Spiritual Influence of Grandmother Pomykala

Probably the biggest influence in my life was my grandmother Pomykala, on my dad’s side, who I totally adored. She was very influential. She sparked the psychic side of myself, the Russian side of myself, the gypsy side of myself. As a little girl, growing up, she lived in a small house that had been a garage. After she married, she and my grampa were going to build a house, but, because he died, she just stayed in the three-room house with a little bath. She was colorful! Turquoise house outside, a lavender kitchen, pink appliances, and always, it just felt very homey when I visited.

She would have me curl up and sleep with her, but warned, “Don’t bounce on the bed.”

I never thought about it, but as I grew, I discovered that she always had a Seagram 7 whiskey bottle under her pillow. She dealt with her loss that way. She would drink. She would put us little kids, myself and my siblings, next to where she was going to lie down. She would just pat us, and then she’d start telling us the stories about those relatives that had died, and the spirits, and how they come, and how to talk to them, how to pray with them. She had an altar set up in a corner. I have it today in my own home. It had the Black Madonna, from her Russian Orthodox side. The gypsy side of her had a different way of honoring their saints, and the Virgin was black. I would go in and it was always spooky: the candles were lit, the shades were down. I’d go up and she’d tell me what to do. I’d talk to the dead, and I’d call them in.

Then I’d go to sleep. Every so often she’d wake up and start talking to my dead grampa or someone. She tantalized my interest in the psychic side of things. She taught me how to read Tarot cards from a standard deck. She taught me how to read the weather outside, how to listen to surrounding sounds for what to expect, and what was going to happen when calling on spirits.

Move to a Four-Room House

My Uncle George got tired of watching the turmoil of our family moving around from family to family. He offered to build a home on a lot he owned. My dad’s relatives in the Slavic neighborhood built a little four-room house with no hallways that became our place to live. I soon discovered that I had a brother that was going to live with us full-time. It was really kind of a shocker, because he was this little Southern kid, blond and blue eyed. He didn’t talk like us, and he didn’t look like us. His presence created arguments between my folks now and caused me to argue with this brother. I always perceived myself as the older sibling, and my dad’s family recognized me as the oldest sibling. I was named after my dad. We were both called Andy. My dad didn’t really totally embrace my brother as one of us.

Merril Mushroom: Wasn’t it crowded in the house?

D: Oh, gosh yes! Crowded is an understatement. We girls slept in one double bed. Six girls, we slept crisscrossed, foot to head, head to foot. My brother slept on a cot against the wall. The other bedroom was our folks’ room. There was the living room with a fireplace and a woodburning stove for heat. Then a little kitchen with a water pump outside the door. An outhouse was in the backyard. It seemed sufficient. I didn’t know much better.

I believe that my mother and father were selfish, didn’t have a lot of ambition. They both didn’t want to be parents. Right across the field from our little house was a tavern where my parents spent a lot of time. Drinking, card playing and ugly fighting was built into the culture.

Our family was incredibly poor. I was dirty. I didn’t have many manners. I would stay away from home a lot, run until my legs were tired and just collapse in the house. Our cousins would bring food, or we’d get welfare foods, like big cans of Spam. I hate the smell of Spam when it’s cooking. Or peanut butter in gallon buckets.

Community and Family Strife

MM: Did you have a sense of family? A sense of community?

D: I had a sense of our community, the Slavic community. Many were related ethnically. My grandmother had ten siblings, and my step-grampa Clem Pomykala, he had maybe fifteen brothers and sisters. And that’s the other thing. When my grandmother lost her husband, my grampa Nedelsky, my dad picked out the new husband for his mother. That’s what he had to do. She couldn’t live alone; she had to have a man. My Grampa Clem, the one I always knew, was my step-grampa. He was a nice grampa, but the same patterns of drinking and arguing kept up between them, too.

My mother hated my father’s relatives. She’d refer to them as “your people.” It was like she never birthed children with my father. If we were born in Illinois, we were a a part of “his people.” To think in terms of my community, I would say I had my mother’s southern way of life along with my father’s Slavic northern way of life. Both were extremely different from one another. As I’ve mentioned before, the civil war never ended in my home. I grew up watching the interaction among adults who didn’t like one another.

Move to Suburbia

Around my junior high age, my mother made a critical decision about our family. She wanted to buy a home away from the Slavic neighborhood. She decided that she was going to coax one of my dad’s uncles into buying a house across the bridge, across the railroad tracks, in what was considered a suburban, working-class, white neighborhood in Joliet. White America. Uhhh (a groan).

My father worked for his uncle’s construction company that built water tanks out of town. When my dad was on a longer job, my uncles bought a home for our family. I never fully understood how the exchange happened. My father had to accept his uncles’ decision but never overcame his resentment.

The result was that we relocated out of the ethnic neighborhood into suburban white America, where I would discover a totally different identity as a young teen. My excitement of something different was short-lived as the parent quarreling intensified.

My disappointment was that I would now be seen as white trash in this well-kept white neighborhood. Our family wouldn’t be welcomed by many of the neighbors. And rightfully so! My parents brought their bad behavior. Often, they had loud drunken fights. Police were often called at all hours of the day. My dad threw trash out in the front yard like a burned-up mattress where my parents had fallen asleep smoking and drinking. When they would fight about us children, he threw our belongings into the yard. I never knew what kind of violence might happen day by day. What I knew would be my life had changed. I found it extremely difficult to find friends and to fit into such a different environment. Grama Pomykala’s close proximity and the support of the ethnic relatives would now be miles away. I felt abandoned.

School Days in Special Education

MM: What was it like for you at school? What was it like with the other children?

D: In my younger years, I had teachers who worked in a system that lacked financial support for families where English wouldn’t be the only language spoken. I was in a poor ethnic area. Funding, just like today in 2025, was not available to our school. I personally struggled with understanding English, often hearing a mix of English and Slavic words. There were no tutors. Also, I didn’t attend school every day. If my mother didn’t want to help me dress or there were no clean clothes, I stayed home. If the parents had fought all weekend, I had gotten less sleep, so I stayed home. If the school required me to get supplies like glue, pencils, and notebooks, my parents just ignored the need for me to get them for school. I didn’t go because I lacked supplies. School would be a place I was supposed to go to learn, but it never came true.

I didn’t learn to read or write until later in my life. When I say later, I mean eighteen years of age, after I left my parents’ home. When I moved to the suburban schools I had been tested for reading and writing skills. I failed on all levels. This placed me into special education classes, where in the mid 1960s I would be tagged as retarded all four years of high school. I didn’t have to learn.

School was only a haven of rest for me. If I went, it was because I needed to get some sleep. Being the oldest girl, I became the built-in babysitter of my siblings. My mom did get a job when I was in high school. She’d rather go to work than deal with her children. If one of my sisters were sick, I stayed home.

MM: How did the other kids treat you at school?

D: In high school, I was put in this special ed class with about thirty others. Now special ed meant you were autistic, or you had fits of tantrums, or were blind, or handicapped, or mentally, socially or physically underdeveloped for one’s age. All of us were put into one classroom. We went through all of high school together. We didn’t have to buy our books. We didn’t have to do homework assignments. Fortunately, the advantage of being in a wealthier school district was they allowed us to take art classes with supplies provided. I took full advantage of these classes.

The high school I went to had almost two thousand students. I went from the ethnic school of probably a few hundred students in the rural area of my ethnic community, to the suburb area where every age group class was about four to five hundred students. In my age group, there was only one classroom of special ed students. The difference was, there were also art classes. I didn’t have to go to standard classes. A number of rebellious students ended up in art classes. I did make friends with these art kids, which was good. I did get to hang out with families that were well-to-do, lawyers and doctors. When I visited their homes, I got to see a different world that I had no idea existed. I mean, just because I was tagged simple and poor didn’t mean I couldn’t begin to understand the unfairness of the environment I grew up in. It would be a “Wow!” moment in my life.

MM: What was that like for you?

D: I was jealous. I thought, “Damn! You got it made! You’ve got your own bedroom!” I saw first-hand the economic class, the professional class difference from where I had come from. I went into high school to realize that now I would be a little white American girl in a suburban world. I had to navigate a different life from the one I had grown up in as a non-educated person. I would learn to hide my inability to read and write by fully immersing myself in art. I was beginning to do this little dance of trying to create who and what I was going to be, without others knowing who I had been tagged to be: a functioning illiterate.

One thing that happened in nicer neighborhoods was that Jehovah’s Witnesses or other church groups would come knock at your door asking what church we were going to. Since my family had moved us away from our ethnic family church, we had all but stopped going to any church. One day in 1966, two Baptist women named Shirley and Irene knocked at my parent’s door. When they asked my dad if he had children that might like to go to camp, he agreed he indeed had a daughter. Me. He actually agreed to let me go, which was a shock! Until then I had no freedom. I had been the babysitter, the one that they would loan out to friends of theirs to watch other’s children.

My father and I battled more often. He was determined to make me be like him.

I had my first car hop job at fifteen. My tips went to help pay for the electricity or the water bill or my parents’ beer or cigarettes when they were short of money. But for some odd reason my parents let me go to this summer camp for a couple of weeks. I wouldn’t have to pay any fees if I worked so many hours helping in the camp kitchen with meals. I was excited and hooked. I was exposed to new freedoms without my parents’ control.

A woman counselor I met while there, Margaret, who seemed much older, took me under her wing at that camp. A wonderful thing happened. She didn’t talk down to me. She said, “This is how you brush your teeth. This is how you tie your shoes. This is how you make friends. This is how you do arts and crafts. This is how you get along.” That was in 1966. I was fifteen. It affected me enough that every year from then on, I did go to the camp. I actually joined the board of Pioneer Girls in my twenties. I went for many years to facilitate at that camp, because of a woman named Margaret and her influence over me.

Becoming a “Bull Dyke”

MM: I bet that changed your life at home.

D: I began to assert my “I’m going to do my own thing” attitude. And no, I’m not going to do what you tell me to do. My mother would hit me, knuckle-fist on the head, and say, “You’re going to do what I tell you.” These were the first real physical fights that took place between us.

My father and I battled more often. He was determined to make me be like him. I felt sad and grew angry a lot because I started to internalize the hatred toward my parents. In my sophomore year, my dad wanted me to quit high school and get married. He had married his mother off, and it was time to marry off his daughters. I told him I would NEVER marry, especially his kind. I liked my girlfriends. The second I made that announcement my father went into a violent rage.

This was the first time I heard the term “bull dyke.” Besides naming me a bull dyke, he decided to beat it out of me. As he attacked me with the wooden part of a broom handle, this would be the first time my mother ever stepped in to stop him. Until then, he would slap us kids around all he wanted. Due to the violence we both exhibited, I knew I had changed. My father had lost control over me. From then on, I was more determined to buck him at every turn.

I remember the first lesbian stripper I met in a Chicago bar; I was sixteen.

She would come up and pinch me, and call me “little dyke,” “little butch,” and play with me.

Leaving Home

I started running the streets when I was sixteen. I had a gay cousin, Johnnie, five years older than me, who lived up in the area. He took me under his care once he had heard what had happened between me and my father about my declared bull dyke stance. He actually encouraged me to “go on out there and find friends that are like you.“ I did. I remember the first lesbian stripper I met in a Chicago bar; I was sixteen. She would come up and pinch me, and call me “little dyke,” “little butch,” and play with me. I would learn the new rules for my life.

I had learned more about myself, and by 1968, when the war protest took place up in Chicago, outside the Democratic presidential convention, I went with my cousin Johnnie. He would teach me about protesting. He’d say, “Protest adults, protest their laws, protest their demands over us” to the point that it went through me, in me, to where I carried it home. Anything any adult said, if I didn’t like it, I would protest. I’d just get ugly with adults.

I had become hardheaded but my mother, who never finished high school, wanted more than anything for me to graduate, even at the very bottom of the class. She pushed me to stay in school. For whatever reason, I stayed and received my diploma, even if I couldn’t spell the word “diploma.” The second I got that certificate, I mean literally, I got a brown paper bag and shoved in my worldly belongings: clothes and little trinkets that I had saved in my life that were special. I moved in with my cousin’s friend, a prostitute, above a tavern. He had told her I was a little baby dyke. I had to pay her some amount of money to sleep on the couch. When she had her clients in, I went downstairs and would sit at the bar until her clients left.

MM: How did you get the money to pay her?

D: I had worked since age fifteen. I worked in a nursing home serving meals by age sixteen. I didn’t have to read, just ask for a job. As a young person, nursing homes were the best place for me to get hired. They needed someone to do the laundry. I could cook, clean, and swing a mop. I didn’t have any skills outside of that, so my jobs would be in that environment for a long time. Never had to fill out an application once hired. All you had to claim was experience at other nursing homes.

My parents had gotten heavy into drugs while I was in high school. I had begun to see myself sliding down the same habits of my parents. I had run the streets. I hung out with the artists and other dykes like myself. I never had relationships. Because of the violence of my life, I would be a “Do not touch me” person. I had a quick temper if something would seem wrong to me or I felt an injustice.

Move to St. Louis and a New Life

Somewhere along the line, in the early 1970s, a light bulb went off in my head. I told my roommate that I had grown tired of sleeping on the couch. I was tired of how my life had no purpose. “I’m out of here!” I had this old car that would get me around town. I put myself in it and drove out of Joliet and said goodbye to a life that I knew would have either landed me in jail or caused an early death. I must have been half out of my mind. But I went south.

I headed for the St. Louis area, because I knew that Margaret lived in a little town near there. This is Margaret that I met in 1966 at that Baptist camp. She had sent me mail over the years to encourage me. I had an address, but I had never left Joliet. I had very limited reading skills, but I had my bravery, along with extreme naiveness. I was determined to find her. I believed that when I found her, she would know how to guide me. And that’s exactly what happened.

This was the time of the hippies and the flower children. I knew that if one smoked pot there would be a welcoming commune somewhere. I had indeed landed at a good open commune, where the people gave me advice on how to navigate the area. Remarkably, I landed a few miles from where Margaret attended church. One day I walked through those church doors and looked around. There she stood in the foyer. “I’m here!” (nervous laughter) “I’m here, and I need help, and I need a change.”

She acted just like I had met her at camp many years prior. She welcomed me without question. She was not a lesbian, and I don’t fully know if she thought of me that way, but she had the heart of gold. A good person. Without hesitation she said, “Okay!” She introduced me to Liz and Ron Stevens, a Christian family from her church, who had two children. She shared my situation and asked if they would let me live with them. Again, there was an instant yes.

This family didn’t push marriage. They didn’t push me to be a Christian.

They pushed me to be a good person. They encouraged education and learning as important.

MM: Psychic convergence!

D: Totally! Totally! I lived with them and got a job at a nursing home just up the road. I had agreed to pay them $20 a week. My car had broken down so I walked to work for a while. The man who had hired me agreed to buy a used car so I could go back and forth. He would hold the title and take the payments out of my check until it was paid off. I agreed. This is where I would learn about trust.

The Stevens children, Sarah and David, became my teachers. Liz instructed her children to sit with Andie after school and read grade school books together. (Andie was my nickname at camp, and that is how I was introduced to the Stevens family.) Sarah and David found me fun to play board games and ride bikes with. I believe they found it interesting that I couldn’t read or write very well. They were my tutors for the next year or so.

MM: How old were the kids?

D: Sarah was nine, David was twelve. They were fascinated. I would be like a playmate, only older. I had fun when I wasn’t in this situation of my family with all the adult responsibilities of raising my siblings. I learned to laugh for fun. I loved everything about the world that I would learn about. It was exciting. I was willing to change; I was willing to be the person I wanted to be! This family didn’t push marriage. They didn’t push me to be a Christian. They pushed me to be a good person. They encouraged education and learning as important. I was influenced by them, and I was influenced by Margaret.

Going to College in Kansas City

During that period of time, I joined the Latin-American missions. I served for nine months in Mexico as a missionary with Margaret, who had volunteered to work with the orphan children. The Church paid for us to serve and covered all our expenses. I learned a lot, but after that experience, I decided it was time to get a real education.

I learned that Liz and Ron Stevens had gone to school with the president of Calvary Bible College in Kansas City. When I returned from the mission field, Ron called up the president of the college. He spoke with him about me this way: “We have this young girl (me), who can’t read or write, not well, but she’s spunky and she’s a quick learner. Will you accept her in school?” He said yes. I entered college without any transcripts. The school managed to get me a scholarship for my learning disability. And off I went! This time heading westward.

I went to Kansas City just like when I left home with my little brown bag of possessions. Only this time I felt like I had purpose. I entered this college that wasn’t heavy into pushing extreme Christian teachings at that time. I could earn a teacher certification. I thought I could get certification in camp recreation. I didn’t understand how degrees all worked. I knew that if I got training, I could get a better job, make better pay.

Unfortunately, the college president would be voted out and the new board would set new guidelines for their students. As a student, I had to sign a mandatory agreement not to participate in any homosexual groups. The money people, the newly elected board, decided that the college would become a more religious school. not an open school for anybody who wanted to come and get their degrees. I had one full year of wonderful teaching, but the school policies changed.

I knew that I was a dyke, a lesbian. I had already met people there in the LGBT community who had worked on their teacher certification. Also, I met my first girlfriend there, Pat. The school now came under review for losing accreditation for certification. Some friends felt totally comfortable in the environment of the school. Once I had to sign the agreements not to be a homosexual, though, Pat and I, along with others, left the college.

Finding PFLAG and a Path Forward

In 1973, PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) formed in Kansas City at the Presbyterian Church. The church was located in Midtown, close to where I lived in a house with Pat, two gay guys, a lesbian, and a couple of other artists, all in this one big house. When I discovered this new PFLAG just up the road, I went there. They had little circle groups they formed. I shared my family’s lack of acceptance. I had grown distant from their way of life. I would go see my family once a year at Christmas. My life had really gone different ways from their drinking, drug, and party lifestyle.

Although I was far away in Kansas City, I still struggled dealing with my parents’ expectations of me. They were tired of raising some of my sisters who were acting out, so they sent two of my sisters, at two different times, to live with us. One sister stayed a year and graduated from high school. One sister that I couldn’t handle got in too much trouble in Kansas City, so I sent her back home. It was a constant financial struggle, too. My parents kept asking for money to pay their mortgage, so I had to find a lot of extra work. I was grateful to find PFLAG that helped me get focused on going to a community college.

Since I had lost my scholarship from the Bible college, I now had to figure out work. Pat and I both got jobs at the Red Cross, and I eventually got promoted to work as assistant to disaster response. Since I didn’t have a degree, I couldn’t get the director’s job, so I quit. That made me more determined to get a degree and also to make better money. Pat stayed on a few more years before getting a job at Hallmark cards. She stayed at Hallmark until she retired.

After the Red Cross, I cleared out people’s garages and did yard work. During this time, I met Mr. Meyers, an older man who hired me to pull boilers out of apartment buildings. He needed somebody he could boss around, young and strong. I convinced him I could do the work if he taught me along the way. He had me work various jobs at the apartment buildings that he owned. This salary allowed me to start college classes.

I started to learn trades. I was going to Penn Valley Community College in Kansas City, where I took art classes along with tech classes in HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning).

There was a push for discussion groups about LGBT communities at school. Being an out lesbian at the college, I got invited to represent my community on panels with the drag queens and other out gays and lesbians. Those of us who were out were in demand in the early 70s., “Come tell us about how you’re being discriminated against. Talk to us.”

Finding MCC, Women’s Liberation, and Gay Pride

In 1975, I landed at MCC, the Metropolitan Community Church, founded by Troy Perry. Perry had started a church in Midtown, near Penn Valley College. I got involved with MCC. I think it was John Balboa who ran the church, and he encouraged us to be our true selves. Pat and I made a lot of friends there. Eve Eggleston became a friend I worked with and hung out with for years. I joined the MCC softball team. The open leagues meant any group could pay dues and form a team. This meant the straight teams also played through Parks and Recreation. Out lesbian ball teams often got booed or hollered at by a few, but we were there to have fun.

The first gay pride in Kansas City was in 1977.

Leah Hopkins organized it through a gay group called Christopher Street.

The other thing that came out of the MCC was a Women’s Liberation Union that used that space to do the first ever Gay Pride event openly in Kansas City. I got to do that. I felt like part of a community. I think it was in ’76 that they had the protest against the Republican National Convention. Those of us who were out protested. What did we have to lose? Our careers? I couldn’t even be hired as a substitute teacher as an out lesbian. I understood there were those [lesbians, gays] who had children to support or could lose in custody battles. I believed I could be out for many who couldn’t.

The first gay pride in Kansas City was in 1977. Leah Hopkins organized it through a gay group called Christopher Street. Leah, who I just adored, was a beautiful African American woman. She put me on the dyke security team. I had always been called a little butch dyke, and she said, “You’ll be good!” I had to wear armbands with the pink triangle. The parade with all of our drag queens was maybe a mile long. The police stood up on the hills where they could watch. We marched, but they had let our group know they planned no involvement. Along the way, people threw things at us. I and others were available for safety in case somebody jumped onto a float or tried to pull the drag queens off the float. I had been involved in Kansas City from a political standpoint of “Out and Proud.” I was learning!

Womyn’s Music, Lesbian Connection, and Becoming a Home Owner

In 1978, the Lyric Theatre had a music event. I’m going to say it was Teresa Trull. I remember being so impressed that they had somebody that did sign language. But the cool thing about it was, I went to it. I thought, “This is lesbian music, women’s music? Many years later I learned that Mary Ann was there. She didn’t live in Kansas City at that point, but she had driven from her small-town school to go. Our paths didn’t cross that night but six years later we met.

I learned about Lesbian Connection. I would start to get exposed to the broader world of lesbians. Pat and I had been renting in the gay ghetto, and the rent kept going up, so I decided I’d buy my own house in the gay ghetto. I couldn’t get a loan, because I didn’t have a good enough job. Banks didn’t loan to a single wommon unless she had a male cosigner. I didn’t have anyone. I looked at these rundowns, usually for sale by owner, that were boarded up houses that the owners wanted to sell before they burned down. I found an owner that would carry the loan for $10,000 for a run-down three-story brick house on Harrison Street. I bought my first home in what would, ten years later, become Womontown.

Pat and I had been together ten years, and she really wanted to have children. I didn’t want that kind of responsibility. So when I bought the house, she moved into an apartment in a building I managed. Not long afterward she met a man and married. We are still close friends to this day. I’m an auntie to her three kids and her grandkids.

The other thing that happened in 1978 was the Southern Baptist Convention with Anita Bryant and her “Save the Children” anti-gay campaign. Through MCC and other groups, I joined the protestors with the posters saying, “We Are Your Children” and “Stop the Hate.” I stayed involved for the right to be my true self.

The AIDS crisis hit in the ‘80s. At MCC church in 1981, people started getting sick and dying. That’s when the politics shifted from just trying to get our rights to just trying to keep our gay men from dying. The lesbians were just as fearful for we didn’t know if we could get it or not. Those of us who had been out in the community in some way were still out there, but many people disappeared back into the closet. A very rough time in our community.

In the gay ghetto, gay guys had bought homes, too. The MCC Church was located just up the street, ten minutes from my house. In time, the houses around me were being left vacant. The people disappeared. They went back home, or died. I remember doing fundraisers with MCC, trying to raise money just to make sure the sick guys had blankets, food or transportation home to their families that would accept them back. A number of families wouldn’t even take them back. I felt helpless; it was hard to watch so many of my friends I came out with disappear.

A few years after I bought my house, my mom sent my dad to live with me. He had become a full-fledged alcoholic by then. He tried to help me with some of my home renovations, but he really drank too much. When I was at work, he’d sell my tools to anyone who walked by the house just to get money for alcohol. When he finally admitted to me that drinking was more important to him than any family, I just couldn’t help him anymore. I no longer trusted him. After two months of dealing with him, I had to send him back home. It was very sad. He died less than a year later, in 1984. He was only 52.

Right around the corner from where our primary home was located in Womontown, my good friend Floyd died. Here today and gone tomorrow is how I dealt. I remember just thinking, I don’t know how to deal with it, try to be busy. But I just did accept it. Of course, I still see the prejudice in 2025 with AIDS programs being cut today.

Kansas City Women’s Support Group (KCWSG)

The other thing that was going on at that time was a group called the KCWSG, Kansas City Women’s Support Group. The assistant pastor, Pam, and her partner Patty, who were good friends of mine, started that group at MCC. But due to the AIDS situation, they stepped back. I remember Pam saying, “Ski, (my other nickname back then) would you take it over?” I said, “I’ll take it over, but I’m not going to take it over under the church. I’ll make sure we have our meetings but not in the church.” They agreed and, from that point, I organized the group for the next ten years.

It was an odd time, because in the gay community in Kansas City, we were culturally mixed:

African American women, whites, and some Latinas.

But at Pete’s Bar, black women went upstairs, white women stayed downstairs.

I would meet Mary Ann just a couple of years later, in 1984. She had heard about the group I facilitated that met in different women’s homes monthly. The group organized retreats, canoe trips, and potlucks for our lesbian community Many of us were tired from daily discrimination in our lives. The group provided a way to integrate playtime and safe space outside the bars. Another ball team, called “The Independent Women,” formed through the KCWSG. By then, I had met Mary Ann, and she was involved with KCWSG in that 1985 ball team. They said, “Put me in, coach!” (Well, I would be the coach.) When I met Mary Ann, I said, “Don’t you want to play ball?” (laughter)

MM: I bet you did! (More laughter) And she did!

D: She did! I had just met her in 1984 at Pete’s Bar where I had been a part-time bouncer and ID checker. It was an odd time, because in the gay community in Kansas City, we were culturally mixed: African American women, whites, and some Latinas. But at Pete’s Bar, black women went upstairs, white women stayed downstairs. I checked the IDs. I can remember thinking, crazy! How the bar was still segregated by color. Of course, I’m not sure what politics were at play. I do know bar owners paid off police. Probably if black women were out of sight upstairs, cops didn’t harass Pete’s as much as other mixed bars.

Another good friend of mine, Jean Green, who I met at PFLAG, was a very dark African American. She couldn’t come in and be on the same dance floor with me. We used to razz about it. We were both butches, and we would just cuss the hell out of Pete and her partner but they kept it light. They had to deal with the politics of the day. The police would come in, raid the place. Bad enough they’d come, but if there were black women downstairs, I’m not sure what might happen. “Just stand there against the wall, don’t anybody move or breathe” until they’re done calling you whatever names they’re going to call you. Then they’d leave.

Mighty Dyke

My activism had been heavily entrenched in Kansas City. I’ve always been pretty much out. On one of the KCWSG canoe trips, I came up with the story of Mighty Dyke. (I didn’t spell it politically correct for the time. I do today, Myte Dyke.) Ever since 1985, I shared stories about this special character. Later, I related it back to the beginning. I was born a lesbian, a Myte dyke. I look at my life like a full circle.

From the time I met Mary Ann, it became the story of how we brought together different groups,

how we later became known for the Womontown movement and all the other stuff we do.

The love of my life, Mary Ann (now known as Leaf, her crone name), entered my life in 1984. She changed my life for the next forty years. She introduced me to academia, to writers, to readers, to artists, lesbian festivals, feminist gatherings. I had none of that as a background. I only had the tradeswoman, rough, tough, protected side of me. I had the dyke-dyke, and I didn’t have that feminist side. I didn’t know who my shero’s were. Those that I know went before me, I would read about later, during Womontown. I didn’t know any of the famous feminists. They weren’t in my world. The drag queens were in my world, the rough out people were in my world, the political “keep the police away from us” had been in my world.

From the time I met Mary Ann, it became the story of how we brought together different groups, how we later became known for the Womontown movement and all the other stuff we do. Even today we are very strong activists—

MM: And writers, and activists, and a perfect segue to the interview with the two of you.

Drea D: Before we start that interview, I want to recap. From 1968 to 1972, I was doing nursing home jobs, and I was not educated. From 1973 to 1990, I was a self-starter. I built my own maintenance business from the ground up, where I met a lot of businessmen who were property owners. They enjoyed having a young dyke with trade skills, like electrical, plumbing, and carpentry. I had been able to develop quite a skill level that took me out of nursing home work to where I would run million-dollar businesses, getting myself hired under HUD (U.S. Dept of Housing and Urban Development]. I also went ahead and got myself a real estate and broker licenses in ’85, which I hold all the way to the present.

I want to clarify that there was an educational process during those ten years of finding myself. I took nighttime classes while I worked during the day. I stayed active with the women’s community, but I wasn’t aware of the lesbian-feminist community. I did Pride marches, I had been an activist in that way, but I hung out in the trades world, lower education, not totally aware of what was going on, until I met Mary Ann in 1984. There had been a gap to learn about the women’s community, trades community, educational community. From age twenty-seven to thirty-three, my life was educating myself, getting myself a degree—actually graduating with honors. In 1982 I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Missouri at Kansas City. I moved on so I could use clout against the wealthy and the political when we created the world of Womontown, and joined other lesbian feminist activist movements, and the politics of it all.

I made two or three career changes. Being in the trades, I was looked at one way. By the time I got to my mid-forties, I was in a position where I could demand better salaries and end up with some security. From 1993 to 2015, I began doing things in the spiritual world, setting aside a lot of the trade stuff, so that we could help grow the effects of Womontown later by participating in womyn’s spiritual gatherings later in life.

The last thing I’d like to mention is that when I first created Mighty Dyke back in the early ‘80s, I spelled it “m-i-g-h-t-y” because, again, I was not aware of how words worked. After I met Mary Ann, Leaf, I now spell Mighty Dyke m-y-t-e, with a full emphasis on the M-y-TEE Dyke, as opposed to the patriarchal way of spelling it.

I just wanted to clarify that it was a journey, but I didn’t want to leave it hanging that I never educated myself. I did. I wasn’t into the feminist community—obviously I am now—then that pushed my activism to where I am today, fifty years later.