Marie Steinwachs: Waste Warrior and Environmental Champion

Interview by Rose Norman in Melrose, Florida, on July 20, 2024.

Rose Norman (RN:): I’m interviewing Marie Steinwachs in North Florida, where she lives with her spouse, Corky Culver. Marie, you have spent a lifetime on a broad range of activist projects, almost all connected to environment and sustainability, in your career as well as in your personal life. I would consider all of these actions to be broadly feminist, and mostly lesbian feminist, in the sense that lesbian feminism considers the way social justice movements affect women, especially lesbians.

What motivated you toward activism, starting with your family upbringing? Where did you grow up, and what was your family like?

Marie Steinwachs (MS): I was one of five kids in a Catholic family. I was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1954. Our home, my childhood home for the first ten years, was a little farm that my parents had, started by my grandfather. It was more like a hobby farm, but we had an orchard, a big garden, a barn, horses, chickens, and various other animals. Behind us was a big estate, three big estates actually, and they allowed us access as long as we didn’t do anything destructive and we opened and closed the gates. I was able, at some point, to wander back there with friends and my sister to just explore nature. That was really important to me, and I think important to my parents, to engage with the outdoors, the environment.

RN: What were your parents like?

MS: My parents were pretty cool. In New York, my father worked outside the home and my mom stayed home with five kids, or whoever was left at home. My parents have always had a balance of power. They remained married until my father died at almost 99 years old, so they were married something like 69 years. There were power struggles with them sometimes, or disagreements, I should say, that they yelled out. But both of them really gave us a lot of freedom and encouragement.

My mother is a force of nature, even now at age 93. She lives independently, drives, and has good friends on her block. She is smart–maybe has a photographic memory–and she is knowledgeable about politics, sports, the stock market, and local and international affairs. In her youth, Mom rode horses, had a band with some girlfriends, and took business courses at college. When she reached mid-life, she fulfilled a dream by getting her pilot’s license. My parents’ honeymoon involved driving from Buffalo, New York, to Fairbanks, Alaska, and camping along what was then a gravel road most of the way.

Biographical Note

Marie Steinwachs grew up in Florida, coming “late” to Southern feminism after a successful environmental career spanning the United States.

Marie’s parents encouraged her curiosity and adventurous spirit from an early age. She made the most of both, taking off from Venice, Florida, at age eighteen to hitchhike across the country, beginning a relationship with many locations and endeavors. Marie met each with enterprise and enthusiasm.

After a stint at the community college in her early twenties, she earned her master’s degree through a Truman Scholarship. Marie wrapped up her impressive career as the technical director of waste diversion for the University of Florida. She is now taking time to enjoy the environment that she spent so many years serving and protecting.

My father was a very kind man, fun and playful. He challenged us with riddles and puzzles my whole life, which I think helped me later in problem-solving. I had a good family. I had a younger sister who was born with a lot of health issues, and my parents were told that she wasn’t thriving in the Buffalo area climate. We began to explore, taking a long trip out to California one year in the early ‘60s, probably, but didn’t find that to our liking, nor in the Southwest. Finally, we took a trip down to Florida and fell in love with the west coast area.

RN: What was your birth order, and how many brothers and sisters—

MS: I’m the second oldest.

RN: Second oldest, older sister and then—

MS: A younger sister, and then two younger brothers. The boys are the youngest. My middle sister died.

RN: The one with the health problems.

MS: Yes. She finally passed away in her forties. But my other siblings are alive; my mom’s alive at 93. She’s still living alone.

The Early Years

When I had just turned ten, we moved to Venice, Florida, where I lived until I was eighteen years old. I had free rein in a small town. It had many beautiful beaches, and I spent a lot of time riding my bike over to the beach. If I rode the other direction, there was the winter headquarters for Ringling Brothers Circus. They allowed kids to walk around the grounds if you didn’t get in the way, so I thought in some ways the town was idyllic. We struggled financially for a while after my parents left the close support of the extended New York family. My parents opened a little deli in downtown Venice. We did n’t have a lot of money in those early years. I became acutely aware of socioeconomic class issues.

RN: Your father was farming for a living?

MS: No, in New York we sold chickens and leftover vegetables and fruit from the farm to subsidize what Dad earned. He had several jobs. He’d been a security guard for ADT for a while, and he built burglar alarm systems. He was really good with electronics and a whiz with math. He had been in charge of telephone communications across the Yukon and into Alaska and the Bering Strait during World War II.

He and Mom owned a little neighborhood grocery for a while, and a local manufacturing plant asked them to provide meals for the night shift because nothing else was open. They began to serve hot soup in cups and sandwiches, things that people could eat at work without a lot of utensils and things. That led to him and Mom deciding to open a catering business in Florida, along with the deli. They had already served hundreds of people. That proved to be a very good thing. Venice was a small town then, and they were ahead of the curve in the early 1960s, so they cornered the market for that part of the state and did a lot of catering.

RN: You always have food when you live on a farm. But then you aren’t on a farm anymore and you have to learn to live the way people who don’t have a farm live.

MS: Well, sort of, except we had a deli. We ate whatever didn’t sell in the restaurant. We would get a lot of good leftovers. But that family farm sort of stayed in my brain because the canning of vegetables, the growing of vegetables, the raising of animals for consumption and that kind of thing, was part of my early childhood. It came back around to me later in life when I ended up helping manage large pieces of property – an organic farm and a vineyard. I love the country!

Looking for Adventure

RN: Then you went to college?

MS: No…I didn’t go to college at first. The summer I turned eighteen, I took off and hitchhiked across the country. I was looking for adventure, and at that point Venice was stifling to me. I was in high school during the late 60s, the assassinations were happening, the rioting in the streets, the Viet Nam War protests, Civil Rights, Women’s Rights—everything was bubbling and churning. To me, it seemed like the people in Venice were on vacation all the time. I read, and I listened to the news, and I studied things. I felt strongly that I needed to know what was going on. I met a guy, a veteran that had just come back from Viet Nam. He was big, and he wanted to hitchhike with me. So that’s what we did. We hitchhiked out to California, meandering along the way, and then—

RN: What route did you take?

MS: Oh, gosh, southern. Not through the desert, but we probably went out on Interstate 70 maybe. I’m not even sure the interstate was open all the way. There were big chunks where we’d have to get off the interstate, and walk or do something, or we’d detour. We ended up in California, explored a few places, and decided that, by then (this was 1972), it was pretty worn out. People were sick of people migrating to California, looking for the big dream. I had a friend in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and I thought that sounded like a cool place to check out. She invited me to come, and we hitchhiked back toward Ann Arbor—this time we went the northern route —and we ended up in Ann Arbor in November. It was snowing and it was cold, and it was time to get off the road, for sure. I ended up living in Ann Arbor for five years.

From Ann Arbor to Yellowstone

It was really easy for me to get a waitress job anywhere because of the experience in my parents’ restaurant. Within a day I’d have a job where I could be bringing home money, and I did that. I started waiting tables and was trying to figure out what I was doing with my life at the same time I was sampling all the political culture of Ann Arbor and just learning. One of the places I worked was a coffee shop where college students hung out, so I was meeting people and absorbing all sorts of influences there. You know, the first question in the south that people ask you is, “Where do you go to church?” And the first question in Ann Arbor that people ask you is, “Where do you go to school?”

It became sort of embarrassing to admit that I was just waiting tables. I started at a community college two years after I graduated from high school, and then I went to Eastern Michigan University, in Ypsilanti. I engaged with some faculty from the University of Michigan as well–one professor in particular, whose last name was Steinwachs. So of course, we had to connect and found our family relationship, but that’s a whole other story. She was pretty influential in some ways.

I went to school, worked, had a good time, and grew my political awareness in Ann Arbor for a few years. Then there was a bad winter, lots of snow and blizzards. By then I was sort of sick of the whole thing and I decided to go west. In trying to figure out how that would happen, I managed to find an offering for a summer job in Yellowstone Park. I applied for this low-paid position, thinking it would be a steppingstone to go someplace else. When I got out to where they were interviewing for the position, the guy interviewing me said, “I see you’ve got a lot of experience in restaurants. Can you cook?” I asked, “Why?” And he said, “Because we need a cook. You’ll get paid more, have your own room, and have a better—” I was like, “Yeah, I can cook. Sure, I can cook.” I sort of faked my way into being a second cook for Yellowstone Park concession employees. There were about 75 of them in our section, and I did three meals a day for six days a week.

RN: How long did you do that?

MS: Probably May to August, something like that. Then part of the park closed down because it’s often snowing in Yellowstone in August. I went down to Steamboat Springs, Colorado, where I had been before, and thought I’d find a job there. I ended up working three jobs there, just to try to make ends meet because they hadn’t had any snow in two years, and the town was starving (it is primarily a ski resort town). A lot of businesses were at minimum production. I was working as a bartender, a waitress, and a ranch hand, of all things…three jobs to try to support myself out there. Out of necessity, I was living in a trailer with two men I didn’t care for very much. We divided up the space, but not very well.

RN: Had you finished college by now, or are you just…

MS: Nope. No, I dropped out. Anyway, I ended up not staying very long. I’d been there for four months or something when I was walking to a movie by myself one night. I believe it was Star Wars; in fact, I know it was Star Wars. As I walked across the street at the signal light, in the pedestrian crosswalk, I was hit by a pickup truck, and it knocked me into the other lane. I got knocked out. It tore ligaments, gave me whiplash; I felt like I was totally alone. There was a man who I had been involved with while I was in Steamboat, but he had left. I felt like I didn’t know anybody there I could call. Of course, later, all my coworkers said, “Why didn’t you call us?” But at the time I was sort of in shock, so I just went home.

Westward Bound Again

RN: You didn’t go to the hospital?

MS: No, I didn’t go to the hospital because I found out then that when I’m hurt, I come out fighting, and I say, “Just leave me alone!” And that’s what I did. A little while after that, still hurting, etc., I called my parents and said, “Do you need any help down there this winter?” I came back to Florida and worked through the winter (catering), got some medical treatment for my injuries, and saved some money. Then I flew out to California and met up with that guy (from Steamboat) again. I’m sorry, I know this is a lesbian archive, but it was sort of interesting because he was associated with the Whole Earth Catalog and he had been one of the Hog Farm. [The Hog Farm is an organization considered America’s longest running hippie commune beginning as a collective in North Hollywood, California.] He was my introduction into the California counterculture. We always lived with other people, so it was a little bit different from being in a one-on-one relationship because there were always other people around us. But he was sort of “the guy” that I was following at that point.

RN: This is the big guy that crossed the country with you?

MS: Nope. Got rid of him right away. [Laughter}

RN: That’s how you landed in California the first time.

MS: Yeah, this was in California. Different guy. See, it took me a while. We ended up down in the desert. The Hog Farm was trying to raise money to buy a big parcel of land in Northern California so they could have a community there and have everybody together.

RN: I don’t know what the Hog Farm is.

MS: The Hog Farm members were some of the original hippies. If you ever heard of Wavy Gravy, he’s their political clown. I wouldn’t say “leader,” it’s pretty much an anarchy. But people followed them and they did a lot of good deeds. They were at Woodstock. They did the food, the medical, helped with security, had something called the “Please Force” that went around and patrolled people. They took care of people that were having a hard time with drugs. They did all kinds of things. They worked hard. They were a collective of people who had a house in Berkeley where a lot of them lived, but that was pretty crowded for me. They had leased this vineyard in the desert and needed people to grow organic grapes to sell to the food co-ops. Any profits would go toward buying land.

I thought, “Desert! I don’t know, man. I grew up in Florida.” Desert didn’t sound like anything I was interested in, but I agreed to go down for pruning, or something. We drove into the desert in the spring. It had just rained, and every single plant was in bloom. It was the most beautiful place I have ever seen; it was love at first sight.

RN: California desert?

MS: California desert. We were at a place called Desert Center, which was in between Indio and Blythe, and right across the mountain range from Joshua Tree, where three deserts came together. It really was out in the middle of nowhere. The grape farm was out even farther from the town center, which was basically a couple of Quonset huts that served as grocery, bus stop, and gas station. Real small, like a patch on the road, off Interstate 10.

I ended up staying there for over a year and a half managing the grapes. We had 21 acres of little green grapes called Pearlettes that were the first grapes of the season. We grew them organically. We got a lot of good advice from a large grape grower who had gone organic. His family had vast farms out there and a lot of experience. I think he’d studied under Rodale [J.I. Rodale was an early advocate of sustainable agriculture and organic farming in the United States], so he gave us some really good guidance. I began to learn about grapes, and pruning, and how to build up the soil, and to plant clover for nitrogen fixing, and composting large quantities of manure to spread on the grapes. I did that for, like I said, a year and a half, a year and three quarters…some of the times run together.

A Horse Took Me to Arkansas and I Found Lesbians

Then an opportunity came up. A friend had come through as he was leaving the state and asked us to take care of his horse. We said, “Okay,” and then a while later, he said, “I’ll pay you to bring my horse to Arkansas.” I hadn’t seen my family in a while, so I decided it was time to go back for a visit. I thought, well, if we’re paid to go to Arkansas, we can make it down to Florida. So, we drove back across the states, meaning to be gone for a month or so, dropped off the horse in Little Rock, and said we’d be back to explore the Ozarks. I visited family in Florida and went back to Little Rock. That’s when we got in a rear end accident.

We were stopped in traffic and somebody hit us going about 45-50 miles per hour, and just destroyed the truck. It was a full-sized truck with a big, heavy utility bumper and a camper shell on it and everything. It folded that bumper underneath, and it was bad. I slammed against the dashboard about four times because there were a bunch of cars in front of us and a domino effect with our truck rear-ending the car in front, that car hitting the one in front of it, etc. We were all crunched together. Every time one of those cars would hit another, I would go against the dashboard again. There were no seatbelts back then, of course. I was hurt, and needed to do something until we could work out all the insurance mess and my healthcare.

This nice woman, sort of churchy—I don’t even remember how I met her—had just been through a divorce and had two young girls, said she could use the help with the kids, and we could stay in her spare room. We moved in with her and lived there—I can’t tell you how long—a year, maybe, or part of a year. During that time, she realized she was a lesbian, and this was against her faith. We were involved with part of her struggle. She began to bring these gals home from the bars, and I found myself going to a lesbian bar! I helped them make costumes for a variety show they were doing; I sang backup with their performing group. They were fun gals, but, see, I was with this guy…

RN: This was in Little Rock?

MS: Yes, in Little Rock. I was with this guy, but I thought, you know, the lesbians are great! I like them! It’s not my cup of tea, but whatever they’re doing is fine with me. I didn’t mind it, but I wasn’t in love with any of them.

You have to understand that, in my early childhood in New York, we had duck and cover drills

in school and I lived very close to a Nike missile base. Somewhere deep in my psyche

was the idea we were going to go up in a mushroom cloud.

Antinuclear Work

MS: The breakthrough for me in Little Rock was that I began to do antinuclear work. Three Mile Island had just happened while I was in California. We would actually drive to somebody’s house who had a television so we could see what was happening every day. I was really alarmed. When we got to Little Rock, I was on fire about it. You have to understand that, in my early childhood in New York, we had duck and cover drills in school and I lived very close to a Nike missile base. Somewhere deep in my psyche was the idea we were going to go up in a mushroom cloud.

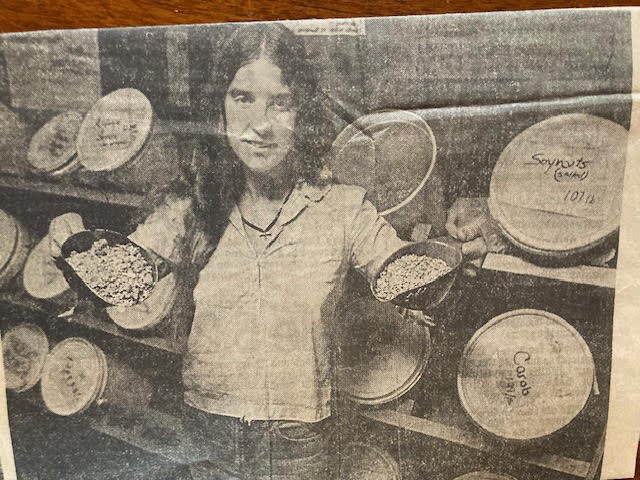

One of the things I always did first in a new town was find the food co-op [cooperative] or where I was going to buy my food, and then find the library. When I got to Little Rock, the food co-op and the library were right across the street from each other. The food co-op at that point was like Facebook or something that linked you to everything. Every place had a bookstore or something as a hub for action; there (in Little Rock), it was the food co-op. The huge bulletin board had every counterculture, alternative thing you could imagine posted on it.

Shopping there at some point, I found out that I qualified to apply for their manager position because it was paid for through CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) grants, and you had to have been unemployed for six months to be hired. Well, I was working in the desert for support and room and board, but I wasn’t getting paid. It worked. I became the manager at the food co-op, which put me right in the middle of all that activity and I began to meet this vast network of people.

There was a lot of political action in Arkansas at that point; Bill and Hillary [Clinton] were in the Governor’s mansion. I quickly found the Heifer Project and Rockefeller Foundation, organizations working on international sustainability issues as well as local sustainability efforts. I met some of the old civil rights activists who had been involved in the Little Rock Central High School integration. At a women’s house, I met feminists who were really engaged with Central America. I began to meet other environmental people.

Sometime around then we were given the state antinuclear program. Some friends and I were the Little Rock Chapter of the Dogwood Alliance and were pretty active. The gals that founded the organization in northwest Arkansas were getting too much flack and intimidation. They had young kids. One of the founders, a farmer, ended up dead under mysterious circumstances.

RN: That would be the Fayetteville people?

MS: No, I think they were in Russellville, where the nuclear power plant was located. They said, “We can’t do this anymore.” So, we got boxes of flyers, signs, a bank account, and a mailing list from them—we had an organization in a box. It became our job, then, to crank up the antinuclear organization for the state. We had a hardcore team, and we began to get more active on antinuclear issues (power plants and arms buildup).

Right around that time, while I was answering the phones at the food co-op, which was also the contact number for the antinuclear group, a nuclear missile blew up in Arkansas. It [the rocket] was being serviced by a mechanic, and an eight-pound socket wrench fell down into the missile silo and sheared off a fuel line or something. The explosion blew this big hole in the ground and blew that poor man to smithereens. It was just awful. The non-detonated nuclear warhead was somewhere out in the hillside in Arkansas.

All of a sudden, here’s me, pretty young still, just getting my activist feet wet, fielding calls from all over the country. I actually talked to Hillary Clinton! I was trying to find out what was going on so I could report back to the Clamshell Alliance and all the other alliances that wanted to know what was happening. That was Damascus, Arkansas where that accident happened.

Ozark Area Community Congress (OACC)

MS: That probably was 1980. We did a lot of demonstrations during those days. I began to hear about an effort that was taking place in the Ozarks; the emerging Bioregional Movement was looking at new ways of organizing for sustainability. I thought that sounded interesting because the issues that they were addressing were water quality, forest management, food production, health care, education, ecofeminism, you know—all the issues. They didn’t say LGBQ (other preferences were not added yet), but it was broad. I went to my first Bioregional Congress in 1980. It was called the Ozark Area Community Congress.

The idea was that rather than having these arbitrary political boundaries,

why not make decisions based on an ecosystem—usually shaped by things like the climate,

the soils, geologic formations, and the watershed.

RN: Bioregional?

MS: Bioregional. The idea was that rather than having these arbitrary political boundaries, why not make decisions based on an ecosystem—usually shaped by things like the climate, the soils, geologic formations, and the watershed. Watersheds were really important in that whole planning idea because what somebody upstream did, everybody downstream felt (“We All Live Downstream” was a popular slogan). That first congress put me in touch with a whole lot of people from around the Ozarks, a much broader network that I even knew in Little Rock. The movement was growing in Arkansas, Missouri, and then Kansas and Oklahoma; there were similar groups in California, around Boston, and beyond. It was also gaining attention around the world with a lot of theory behind it.

RN: This was the first congress, or your first one?

MS: This was the first one, OACC-1, and there were probably about a hundred people who camped out and met on this appropriate technology demonstration farm in the Ozarks called New Life Farm. The property had a methane digester, silviculture and organic gardens, a gray water system, composting toilets, a solar greenhouse, and a passive solar water heating. It was a really pretty, with an old Victorian farmhouse that had been retrofitted to be eco-friendly. All these systems were being demonstrated, plus there were these great comings-together.

The model for the congress involved these little groups that would meet around a topic like water quality, forest stewardship, land trusts, or ecofeminism; usually the people who were already involved or interested in the topic would join that circle. Those people would work together to develop a platform or an action plan, come back and dovetail their ideas with all the other groups (intersectionality). I thought it was a fascinating way of organizing. It was very effective, and some very good things came out of it, like the Ozark Regional Land Trust, and new National Forest Service stewardship practices that replaced clear cutting with selective cutting of trees.

New Life Farm and the North American Bioregional Congress (NABC)

I was still a sponge, absorbing it all, but within that year I was offered a position to go to Missouri and manage the New Life Farm property as a caretaker. I was hired by the woman that had bought the land from the nonprofit organization that organized the bioregional congress. They did not have the resources to sustain the land and the nonprofit. They decided if they sold the land and moved to a little office somewhere, they could keep the nonprofit work going. I said, “You can stay here. You can keep your office here; this is a big house.” I was used to collective houses, so why not have a few more people coming and going? Well, I got real involved, and I proceeded to be one of the main coordinators for OACC-2, OACC-3, OACC-4…and then we put on a North American Bioregional Congress (NABC) in 1984, outside of Kansas City, Missouri.

By then, I had learned a lot of nonprofit skills like grant writing and putting out newsletters, which included layout and paste-up. You used to have to do it with wax and all that. I learned how to organize mailing lists and mail outs. We didn’t have computers then, but we had those great, old IBM Selectrics [typewriters]. We could do some fancy typing!

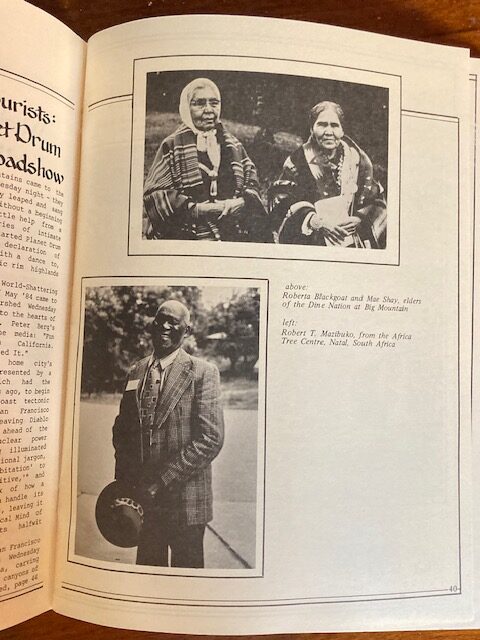

We had about 200, maybe 225 people at the first NABC. We had a man from South Africa who started a movement to plant millions of trees to reforest areas to stop desertification. We had seven different Native American tribes represented, and members of the new Green Party came over from Germany. We had people from all across the country, and some really amazing writers, activists, and artists. Paul Winter came and played music for us one morning at sunrise, out on this little lake at the church camp where we held the congress.

RN: What was the location of these hosts?

MS: We would hold the congresses at different camps that were vacant—state parks or whatever— and we would just rent these spaces for five days. But the first NABC was up north of Kansas City, Missouri. People flew in and out of the Kansas City airport. We had an amazing woman who volunteered to shuttle them from the airport, and she provided all kinds of local support. She was one of my mentors, but that is another story I’m trying to write some day.

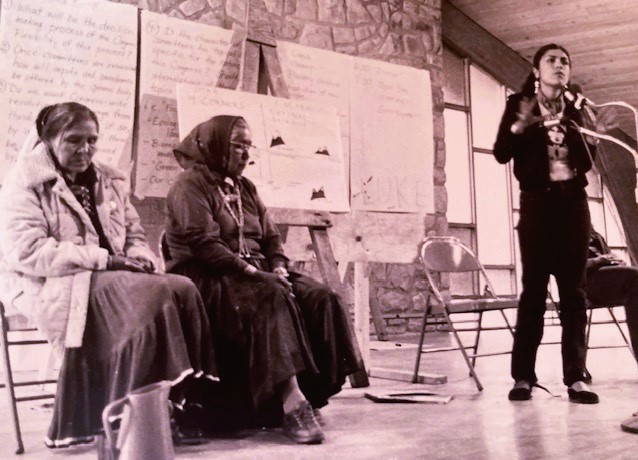

Aid to Big Mountain

At New Life Farm I met a fellow—you know, folks would stop on their way through the Ozarks, you’d always be surprised—and this guy came through on a bus with his beehives that he would position around the countryside. The bus was his home and also held all his bee-keeping equipment. I got to talking to him; he was really involved in the struggle going on at Big Mountain, in the Four Corners area. The government (specifically the Bureau of Land Management) was trying to displace the Navaho people in that area so they could get at the coal and uranium on reservation lands they had mistakenly thought were worthless. That tied very closely to the antinuclear work I’d been doing. I was pretty amazed and upset to learn what he knew about that area. So, I traveled out there with him, this sort of weird guy. He knew many of the Hopi and Navajo people.

I got involved in the Big Mountain resistance. Pelican Lee had done this beautiful slide show of gorgeous photos of the area and a great narrative on the issues to go with it. I took that slide show anywhere anyone would listen to me. I went to college classes, churches, women’s clubs, libraries, and community centers. Every time I went to Big Mountain (three or four times), I’d meet with some of the organizers out there and come back with connections and ideas. At some point, we used the food co-op network, because I still had connections there, to deliver some warm clothes and food supplies out to the encampment. The East Wind community, where I bartered tofu for nut butter, let me use their huge communal laundry to sort and clean all the clothing donations before shipping them.The food co-op responded by saying, “We can take stuff on the back-haul. We have empty trucks going back that way.”

RN: This must have been the Ozark Food Coop?

MS: That was one of them. When I was managing the food co-op, we were part of a larger New Destiny Federation of Co-ops in Fayetteville, and we worked with the trucking collective, which I think was a bunch of dykes [See Trucking for Ozark in Águila’s interview], so it was great. The whole thing ended up working somehow. I just knew who to call, and they knew what to do. That’s how those things happened. I did end up gathering a lot of supplies to send out there and working to make sure they got them.

When we had the North American Bioregional Congress, I’d already been to Big Mountain several times. Some of the Navajo elders came to the NABC and brought that Big Mountain issue back to the Bioregional movement—another cross-pollination of my contacts and careers. But NABC was a very amazing experience. It exposed me to a very high level of awareness.

Along Comes This Woman

I’m going to back up. Right before the NABC, I needed to get down to Florida again to see my family, but I had no means of getting there. I was looking at Greyhound buses because I didn’t have transportation; I was poor and living out in the middle of the Ozarks. A friend said, “I’ve got a friend who just bought a newer car, and she wants to get out of town, take a trip. Why don’t you two go together?” We hooked up by phone and she came out to the farm the night before we planned to leave early the next morning and drive straight through. She was gorgeous. We talked all the way to Florida, and I felt a growing connection to her. Needless to say, at the end of that trip, we were in love. That was 1983. I came back a changed woman. In fact, we stayed gone for a couple more days than we had planned because we didn’t know how reality was going to impact our relationship. But that was (loudly) THE ANSWER to all the problems I’d been having, I thought.

RN: “That” meaning that romance was the answer, or that coming out?

MS: Well, all of it. You know, the guys weren’t working for me anymore. It just—the whole thing was starting to be tarnished. I was lonely a lot. I think what was happening is, a lot of the people I had lived and worked with at the farm would leave for great periods of time and come back, and I was left with a lot of the work. People were splitting up, and going places, and I’d spend sometimes six weeks without ever leaving the farm. I’d be chopping firewood, feeding animals, and maintaining the garden. The guys would come in and ask, “What’s to eat?” You know, I just started thinking the whole thing was not working to my advantage.

So along comes this woman. We thought alike, we saw things alike, and it was great fun. We came back and everybody caught on pretty quickly that some big romance was happening there. At first there was sort of this chuckling and ‘oh, that’s great.’ Then it got a little hostile because I was still working with many of these people, and they weren’t sure about this “lesbian takeover.” There were a lot of other things happening there, but I felt some homophobia.

We all started waking up. We didn’t have feminist consciousness raising groups in our area. I hadn’t even heard about it. But coming together as women, talking, and having woman space where we just felt the difference, that was a turning point!

At the same time, you know how one door opens and another one closes? Well, prior to the serendipitous trip to Florida, some of the landykes that lived in that area started having new moon gatherings in the middle of the day (helpful when you live far apart in the mountains). Somehow, I managed to bum rides to get to these gatherings. I even hosted a couple at my farm. It was all women and everybody came. There were Ozark grannies, there were mothers with passels of kids…

RN: So, it wasn’t necessarily a dyke gathering?

MS: It wasn’t. It was all women, and the lesbians were there. We’d sing songs with Mimi Baczewski; we’d share food and stories; they’d talk about places they’d been and opportunities. The magic started happening. A lot of women started leaving their men at that time. I helped one woman get away from an abusive husband. I didn’t even know he’d been abusive. We all started waking up. We didn’t have feminist consciousness raising groups in our area. I hadn’t even heard about it. But coming together as women, talking, and having woman space where we just felt the difference, that was a turning point!

When I met this woman and fell in love with her, well then, that seemed natural. It seemed really easy. In fact, I thought, “Is that all it is? Does this mean I’m a lesbian?” I felt the same, except, you know, things were different. After six months of romance, she had moved in with me, along with her seven-year-old son. We lived together on the farm for about a year. Then in 1985 we just decided we couldn’t do it anymore. Money was tight and we couldn’t easily support ourselves. You know, it’s hard out there. So, we moved to Springfield, Missouri. I became very depressed, and I rarely get depressed. I was nearly defeated, and thought, “This town is a god forsaken horrible place to be after the beautiful place I had lived for five years.”

RN: Where was the farm?

MS: New Life Farm was in southeast Missouri, not near anything. It was four miles down a dirt road. But we had forty acres, and a swimming hole, and it was paradise. In comparison, Springfield was like a cow town, pretty conservative, very churchy. It was where the Assemblies of God headquarters was located. You know, Jim and Tammy Faye Baker and all that. Very conservative. I thought I was going to die there!

I didn’t know what in the world I was going to do. After a while, I climbed out of my fetal position and said, all right, you’ve got to do something, and I began to look through the yellow pages—you know we had phone books back then—and I thought, what can I be involved in? I thought about recycling.

Environmental Activism in Missouri

It might have been in the desert that I realized that you could pick up scrap metal and get money for it. In Little Rock, I did more recycling on the side, selling old tires to re-treaders [companies that put new tread on lightly used tires] and collecting and selling all kinds of metals. In Springfield, I thought, well maybe I can get into recycling. I found a community betterment association that ran the local recycling program. I walked into their offices and told them I could write a grant and earn my salary if they’d hire me. After some negotiation, they did.

I worked there for a year or so, getting involved in all kinds of programs for low-income people in the neighborhood, including free health services, home repair, GED (General Educational Development), voter registration, and recycling. There were several things occurring simultaneously. The town was growing quickly and it started to have growing pains. One problem was that the landfill was reaching capacity, or they knew it was about to.

We started a group that opposed the incinerator. We began to put out brochures,

pamphlets, press releases. We talked to people, and we defeated it!

City and county officials wanted a landfill expansion, but the local people who lived nearby and would be most impacted stopped it. Then the officials proposed a large incinerator for the city’s waste. I didn’t know anything about it, but there was some overlay with recycling, and I thought I should look into it. First, local environmentalists learned you could generate electricity from the garbage; so why wasn’t our town proposing that? We met with the utility company and city officials. We went around and talked with people and found out that generating electricity was not an option in our area. We went to a conference in Washington, D.C. and we learned more about incineration.

People were mobilizing because this was the time when the waste industry was hoping to locate incinerators everywhere. There were many questions no one was answering, including what would happen to heavy metals in the trash if they were incinerated? I started thinking, hell no, this is a really bad idea! We came back and got organized. We started a group that opposed the incinerator. We began to put out brochures, pamphlets, press releases. We talked to people, and we defeated it! The Chamber of Commerce got behind us because of the cost of it [incineration], and because of something called “flow control,” which meant everything had to go to the incinerator company, no matter how much they wanted to charge. So, we defeated the incinerator, at which point a city councilwoman walked up and said, “I’d like you to be on a committee to figure out what we’re going to do with our waste now.”

Two of us that had been part of that activist group became part of a solid waste task force for the City of Springfield. All in that same time (we’re talking like 1986 now or around there), when waste was starting to be a big issue. I had been interested in a topic called household hazardous waste, which I’d heard about through the Bioregional people, but I could never find anybody working on it. I heard there was something in Boston; I heard there was something in Seattle. I’d write letters (there was no Internet, right?) thinking somebody would connect me to it. Nothing happened.

From Water Quality to Hazardous Household Waste

Then I was sitting in an auditorium getting ready to testify at a public hearing on water quality. The woman who spoke before me, who was sitting right next to me, stood at the microphone and said she was the director of the Household Hazardous Waste Project. After the hearing, I said, “I want to work with you,” perhaps a bit too eagerly. It wasn’t a nonprofit then, it wasn’t anything. She said it was an idea, but she spoke with such conviction that I was sure that she was further along than she was. Well, when I said I wanted to help her, she was afraid I was going to call her out for not having done much. We are very close friends and still laugh about it.

We spent six months researching and writing a little booklet called

“The Guide to Hazardous Products Around the Home.”

She had pulled together a steering committee that included the Health Department, the Fire Marshall, the Poison Control Center, the regulators, a university —she had the right people on board to help us. We were still learning about the problem, but we went to the state environmental agency with our idea, and they had been thinking the state needed to address this problem as well. They said, “You’re further along than we are. If you can become a nonprofit, we’ll give you a grant.” Interestingly, the director of that funding agency had been one of the contacts and attendees in the bioregional congresses. So, he knew who I was, though indirectly, and I didn’t know him but I knew his name and his leanings.

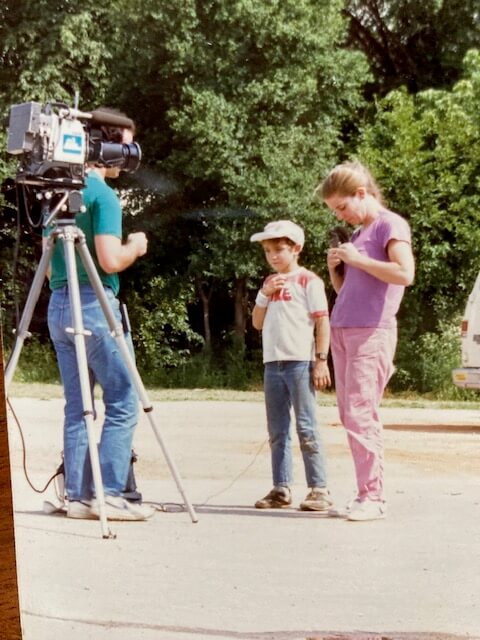

We got adopted by the university and received a small grant (I can’t remember, sixty grand or something like that) to start the Household Hazardous Waste Project. We spent six months researching and writing a little booklet called “The Guide to Hazardous Products Around the Home.” It was made like a little cookbook, with tab dividers, and summarized our findings in sections identifying which products are hazardous, how the consumer can tell whether they’re hazardous, how hazardous products are, and what they did to you and the people around you. We self-published, printed up a bunch of copies, and started talking to anyone interested. We did a lot of presentations. That’s where I learned to be a real bean-counter, you know, count everything: How many people did you reach? How many presentations? We tried to measure impacts all the time.

At the end of our first year, we were already reaching into sixteen counties, so the state gave us a bigger grant and we expanded our reach. At that point, we were starting to look for ways for people to get rid of things that they had, like who would take their old motor oil? I was literally beating the pavement county by county in those sixteen [rural Ozark] counties, finding out where they could take things, going down talking to people, making phone calls. Really on-the-ground stuff. By the fourth year, we were a state-wide program and beyond. We just hit a nerve. Whereas Boston and Seattle had started earlier, their efforts had come out of the local government. Their idea was to have special collections of this hazardous material and pay to dispose of it safely. Missouri said, “We don’t have any money, we don’t have the ability to do collections, and we really wish you wouldn’t talk about it at all. But if you’re going to talk about it, you can’t tell them to dispose of it through the state because we can’t do it.”

This was the George H. Bush administration, and I knew they weren’t much helping

the environment. They were giving awards instead of doing anything significant.

We focused on the front of the pipeline, really targeting the consumers with information. If you buy it, you have some responsibility. This is a consumer product. Do you really want to buy it? Do you know what you’re buying? Do you really need this product? We wrote syndicated newspaper columns; we had all kinds of outreach. We began to network now, nationally, with these other groups that were all starting up in different parts of the country, but most of them still focusing on collection. We were sort of the weird ones.

In 1990, the national focus shifted to preventing pollution, rather than cleaning it up. Our program was nominated for—and won—a White House award for our work, which changed things. It’s hard to get officials to take the kid next door seriously, right? The closer to home you are, or if you’re doing environmental work, or if you’re women, they don’t listen to you too much. But if you get a White House award, it opens doors. I got the game right then. This was the George H. Bush administration, and I knew they weren’t much helping the environment. They were giving awards instead of doing anything significant. I was aware of that. But I thought, if you’re going to use us, we’re going to use you. So, using that credential helped the program really expand. For the next few years, we were able to get in on a higher level of state and federal policy and began to work on that.

International Conference on Women and the Environment

I had a thrilling opportunity—one of my career highlights was to attend the International Conference on Women and Environment in 1991. It was one of the big events leading up to the Earth Summit in Rio De Janeiro. This conference included 1500 women from all around the world. They met in Miami and I got to go down and speak on the Household Hazardous Waste Project and what we’d done.

There were—oh my god – so many amazing women! Bella Abzug was there. I got to shake the hand of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who was a hundred and one years old then and still a strong speaker. It was just an amazing experience for me. I loved it even though I always felt like I was in over my head. I was getting thrust out there (beyond my comfort level) a lot.

RN: Were you closeted all this time?

MS: You know, I was never closeted. Here’s the thing: I didn’t make it my issue. I was ever grateful for the people who fought that battle, but it seemed to me, being focused on the environment, that it was going to muddy the water. I saw what happened at the farm with people that I thought would know better. I didn’t want to fight that fight everywhere I went, where people would say, “Oh, she’s a lesbian,” and close their minds to anything I said. But I’d talk about my partner and my kid (my “stepson,” I called him). People would talk about their kids in Scouts, so I’d talk about him going to Scouts. Why not?

I wasn’t out-front out. I did work with a group to start a little pride center in Springfield at one point. Linda Thomas (I still see her out there in the network) brought me into it. She was an electrician. We raised money and got a sweet little storefront place. It’s still there, to my knowledge. It was more a place for young LGBTQ people to hang out so they wouldn’t feel alone. I was engaged somewhat, and we still had some potlucks and ceremonies with the landykes out in the country.

Truman Scholarship

I was living in the city and, all of a sudden, my career was really demanding. Along about the time when we started getting all these national awards, the woman I started the program with, my dear friend, said, “I don’t want to do this anymore. I want to go walk around the world.” The university where we had housed the program said, “Your program is way too big. We don’t know what to do with you. We don’t know what kind of liability you bring to us.” They said they’d prefer we find another organization. So, we met with our state funder and a lot of different state agency heads to see who wanted us, basically.

The University of Missouri Extension came forward and said, “We know what to do.” Plans were made in 1991 for us to become an extension program. I didn’t have my bachelor’s degree yet. I had gone back to school in Springfield, picking up one or two classes per semester, while doing all this other important work. I felt like school was sort of secondary to what I was learning out in the field. But when the program was going to transfer under the banner of Missouri’s flagship university, and I didn’t have a degree, they said, “Okay, well, the first year you can be interim director, then we’re going to put somebody qualified in charge and move the project offices to Columbia.”

Almost right after they said that, we won the White House award. Then we got invited to another program at the White House. We received a Friends of the United Nations Environment Programme Award and several from EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). We were also recognized by the State of Missouri, as well as by state and local organizations focused on waste and the environment. I was becoming a well-known representative.

Then the university called me with their new plan. “Get your degree as quickly as possible,” they said. I put my nose to the grindstone then and started really working on that degree. I was also working the whole time, still doing household hazardous waste. I think that because we had measurable impacts, the state began to talk to us about expanding into small business waste, which was newly regulated. Backyard auto mechanics, painters, artists, and other people that might be dealing with hazardous material were now going to have to handle their waste more effectively than they had been. We began to expand, but it wasn’t an easy market.

I was working hard at school. I was leaving for the holiday break after a night class on the last day of the semester in what would have been my junior year. I remember empty halls and walking down a stairway and seeing this new flyer on the wall that said, “Do you care about the environment? Do you care about social justice? Equality?” It said, “You might be a Truman Scholar.” I pulled the flyer off the wall, went home, and spent all of my holiday writing this application. Later I found out there was a process, which was supposed to initiate through the college where I was going. I didn’t know any of that.

Long story short—I won it. I got a scholarship that paid for my entire Master’s program. I had entertained ideas of going to Gainesville then, and going to the University of Florida. I actually went down and interviewed.

RN: Was that where you went for the master’s?

MS: I considered a PhD in ecology of some sort; and Florida was ahead of the curve then. They were one of the national leaders in waste research. I thought this was a hot spot. This was where I wanted to be. But I was only offered a teaching assistant job. I would have had to pay out-of-state tuition, and I had a partner and a kid. The decision I made was to stay in Missouri, keep working at 75% time, which would still give me benefits and a decent income, and use my scholarship there. With the high costs of education, I don’t know how people could complete a master’s degree and still have money in the bank; yet that’s what I was able to do.You could use the scholarship funds to pay for your housing and you could use it to pay for anything related to education.

I ended up getting my degree in sociology very quickly then. My master’s degree and my bachelor’s degree are both in sociology because, as you may have noticed, I love movements and how people organize to get things accomplished. At that point, I was reading theories on chaos, self-organization, and quantum physics. And I mean, I just went way into it. I thought sociology was great stuff. I also learned about surveys; and how to measure behaviors, attitudes, and changes more effectively. That was very good.

RN: Was that at the University of Missouri?

MS: No, actually, Missouri State University in Springfield, Missouri. I was still in Springfield. I was still with my partner, the woman I came out with. We continued the new moon gatherings in Springfield, then began to host them, just because we wanted to see and meet women. We met a lot of professional lesbians, really amazing, wonderful women. We had a small group of mostly lesbians that we would meet with once a month, and that was really fun. But again, work, school, work, school—I was into it. At the same time, I was flying all around the country, doing presentations at big conferences, doing training for other states. At one point I got flown to Research Triangle Park [in Raleigh, North Carolina] to meet with all these industry leaders and federal regulators. I was getting challenged in every way. So, the meeting with lesbians and hanging out with women is what I did for recreation and fun, not as part of the “movement.”

Working on the Ground for the Environment

I talked about the experience that I was able to get working on the ground, at the community level. I mentioned the Springfield Solid Waste Task Force; that ended up being a five-year commitment. We came up with the state’s first integrated solid waste management plan. Local officials thought we would choose between a landfill or an incinerator, but we said, “Oh no, we have to have waste reduction, we have to educate people, we have to have recycling, composting, household hazardous waste, market development for the recycled materials, and the landfill.” When that was presented to voters, it won with like 72% of the vote or something, even though it meant it was going to be a cost increase over time. The community got it right away.

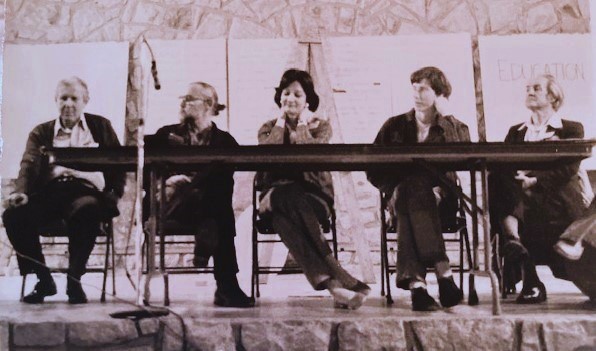

Then I became involved in something called the Community Task Force. The City of Springfield was growing exponentially. They wanted to do some advance planning and also deal with the social inequities in the town, and figure out how to address poverty issues when the federal government was cutting back on social services. This was something coordinated by United Way, and I chaired the environmental part of that effort. The committee I chaired represented every group in town that was doing anything related to environment: Audubon, Sierra Club, the regulators for air pollution and water quality, population control advocates. We would feed them so they’d be able to come on lunch hour, and then I’d report back to the larger group that included chairs from each of the committees (i.e., education, health services, recreation, art and historic preservation).

Because, as lesbian feminists know, all these issues are connected.

You can’t scratch one without hitting the other.

I’ll say the environmental outcome of that, another five-year project, was that the way the city developed left lots of green spaces and bike trails along rivers that connected schools and parks. They planted lots of trees or preserved the trees that were there. Springfield, which had seemed like a very conservative kind of town when I first landed there, is now what I would call a pretty cosmopolitan little town. I’ve heard it described as a conservative town with progressive values, or a progressive town with conservative values. But it’s a mixture of both, and it’s very nice what they did there through collaboration. I love seeing that model played out. It was very much like the bioregional congresses that we did: small circles, feeding information through larger circles and interconnecting those issues. Because, as lesbian feminists know, all these issues are connected. You can’t scratch one without hitting the other.

I also worked on the state level in the 1990s; I was appointed by the Governor of Missouri to the Hazardous Waste Commission. During the seven years I did that, which was the same time I was doing all this other activity, I would go to Commission meetings around the state. We oversaw superfund sites. I’ve been to Times Beach, Weldon Springs, and I’ve been to a lot of horrific places that were in the process of being cleaned up (or still involved in litigation), including the lead contamination around Joplin, vast areas of contamination that they were trying to remediate, even as new disasters were being discovered or created. We also did legislation, rule making, and hearings.

That was a very difficult commitment for me. But when the governor asks you to do something, and he was a good governor, of course you do it. I did it as well as I could, and I tried to have an impact where I could. A lot of it was dictated by lawyers and rules about what we could do, and I sometimes felt like we were just giving industry a license to pollute, within regulatory limits. I had to be impressed with the efforts to clean up these impossible environmental situations that the state had inherited, and I got to see that close up.

Going National and Teaching Locally

The national work I did started out with household hazardous waste, then began to include engaging manufacturers to help solve the problem. I worked with paint manufacturers, electronics manufacturers, policy makers, the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency], and legislators. I beat the halls of Congress a few times. We did things that actually sounded like they were relaxing some environmental regulations but were, in effect, making it more possible to do the right thing. I worked on a lot of those issues and organized the national household hazardous waste conferences. By then I was on the national steering committee.

I finally moved to Columbia during my last years in Missouri. I was on the University of Missouri campus doing continuing education and training on waste, teaching engineering students, and managing a summer intern program. I was more focused on large industrial generators of waste, and teaching students to equate waste of any kind, whether it be water, energy or raw materials, with loss of profits, a loss of money, and an increase in liability. I taught that course every semester for about six years.

RN: This is a course in the Engineering curriculum?

MS: Yes, I developed and taught an undergraduate Engineering course that was online and very interactive. I’m not an engineer, so I had to learn everything I wanted to teach and I validated all the technical part with Engineering faculty. We were a trio of women, one of whom was a software wiz from South Korea. She helped me with the interactive technology part of it. The other was a chemical engineer genius who helped me with the engineering part of it. We used a simulated factory model that was developed in Iowa that we were given permission to use. Students were able to virtually, with pictures and lots of information, see what a factory looked like. They were able to track the entire production process, starting with where the raw materials came in. The students could monitor how many products they manufactured, how much energy and water they used, how much waste they had at the end, and how much profit they made.

We taught them every scenario we could think of that they might find in a real company. In teaching them how to break down a massive process, we just had them follow the raw materials coming in and walking through assembly lines. It was hard for me. I had to master a lot of math and science, very challenging. But I did like the teaching and working with interns in the field where they would have a paid summer job in a company. We would actually go in with our equipment and test things, then write a comprehensive report of environmental and cost saving potentials. We saved companies a lot of money, and many of those kids got good jobs afterwards. One of my students used his intern experience on his application and was accepted to Oxford University [in England]. They used the experience to advance their careers, and they never lost their environmental concern. I thought that was a success.

Then I got tired. It was hard to keep working at that pace. My relationship with my first true lesbian love was coming to an end after thirty years. The son I helped raise was grown; he had his own kids. I wanted to come back to Florida. I felt like Florida was home all those years. My family was here. Finally, I ended my career at the University of Florida. They basically made me the “technical director of waste diversion;” and they turned me loose on the campus to find waste and to get rid of it any way other than disposal. [Laughter]

RN: Did you make up that job for them?

MS: I helped them make up the title. We brainstormed about it, but they didn’t have the real clear idea, they just knew that they had a lot of material that was going into the waste stream that could go someplace else. The biggest project I set up was a large composting operation for all their campus landscaping waste and leaves. Every year they replaced the turf on the athletic fields, and they were hauling all that sod out of the county to dispose of it.

We cleared a site right at the edge of campus for our operation. It took a couple years to refine the process for doing a large-scale composting program like that—finding people who had the right equipment we could borrow when we needed it and figuring out the timing. Finally, we came up with a winning formula: right after school ended in the spring, athletic fields would deliver their old turf, we would mix it with the leaves, start the new long, tall piles called “windrows,” screen the compost from the previous year’s windrows, and spread the finished compost on the athletic fields before they re-sodded. It saved the university tens of thousands of dollars a year doing that.

I think that was because I would follow opportunities after my own heart.

We also sent a lot of materials that would otherwise have gone to the landfill (furniture, office supplies, excess building materials) to nonprofits that could use them. We did another program with a commercial composter for the food services on campus. Wherever I could, I worked to divert waste and, of course, measure everything. You always gotta prove it!

That’s how I ended my career, and that was kind of fun because I didn’t have to raise my own program funding. I reported my results to the management, but I didn’t have to defend my position to anybody. I had a salary that I didn’t have to go out and write a grant for every year. To me, that was an easy job, and a wonderful job, and I loved the people I was working with. But that was it. I told them when I came to the University of Florida that I was going to retire at age 65, and on my 65th birthday they had a party for me, and I was gone.

RN: You know, it strikes me that your whole life you have created your own jobs and made the things happen that you wanted to have happen.

MS: It’s true, and I think that was because I would follow opportunities after my own heart. The nonprofit part of New Life Farm was already housed on the farm I was caretaking, and all I had to do was agree that it stayed there. But I wanted to be involved in it, and so I figured out how, first as a volunteer and, when they saw what I could do, they all decided to hire me. Then I became part of the grant writing team and once I knew how to write grant proposals, of course, it opened opportunities. I had a lot of help with grant writing at the universities. I would develop the game plan for what we were going to achieve and create a budget. But the university would complete all the federal grant forms and the structuring you have to do.

I grew up with this awareness that the world, to me, was not a place suitable for kids.

I didn’t want to be responsible for bringing them into the world.

I guess that was part of my early feminism – avoiding getting pregnant.

I didn’t do regular jobs very well, I’m afraid. I couldn’t easily—I don’t even know how many regular jobs I had, to tell you the truth. I know I did freelance writing, and photography assistant, plant nursery work. It’s just hard for me to do a job only for the pay, but I would work hard for something I was passionate about!

RN: Let’s go back to lesbian feminist activism, which I see as an umbrella term—anything a lesbian feminist does is lesbian feminist activism. But where did feminism find you, or you find it, and how did it connect to the rest of your life?

MS: Well, okay. First of all, my mother’s a—what do you call it—an adventurous woman? She and my dad shared the power, so I never grew up with a model of women being subservient in any way. Women were a strong influence in my life, always. As soon as I became sexually active as a teenager, a friend’s mother (who I would say was a very wise woman) got me on the pill. I don’t know how she did it. My parents might not have approved of that, but it saved my life. I never wanted to have children; I grew up with this awareness that the world, to me, was not a place suitable for kids. I didn’t want to be responsible for bringing them into the world. I guess that was part of my early feminism—avoiding getting pregnant.

Feminism was a sort of dawning. I was really tired of the guys thinking that they called the shots when the women were actually doing all the work.

Dawning Feminism

I never wanted to get married, I never wanted to do any of those traditional things. I’d never had the calling, or whatever you’d say, for that. I helped a friend get an abortion when we were in high school, and at that point you had to fly to New York. I think we went up to Sarasota, which was the big city, and met some feminists: they were tough looking women, they scared me and at the same time I was impressed. They were so competent and reassuring. I felt like my friend was in good hands, and I remembered those women always. I worked with women everywhere, even the grape farm. The guys would be off tinkering with tractors for some reason, and it would be the women out in the fields with our big hats, pruning the grapes and singing. It was always women, it turns out.

Feminism was a sort of dawning. I was really tired of the guys thinking that they called the shots when the women were actually doing all the work. With me, it was a growing resentment about that kind of BS. It was really when I started getting together [with women], through women’s gatherings, that I bloomed. Maybe I really bloomed when I finally got to Gainesville—the women have been doing it down here for decades—but maybe I’m still blooming. I can’t remember when I didn’t feel the right to judge men that thought they knew better than me, and I knew they didn’t. Challenge authority! Question authority!

RN: You didn’t have consciousness raising groups where you were? It doesn’t sound like you needed your consciousness raised.

MS: Oh, I could have used my consciousness raised a few times. I mean, when you get in a relationship with men, there are some preconceptions. They were different; none of them were the normal ‘let’s settle down, have a family’ kind of guys, but I don’t know. It was hard. When I finally realized there was an alternative, well, that was good to know. That was really helpful! I think it was a slow dawning with me, but it started out with never having those expectations put on me that I had to grow up and be a girl that got married.

My parents gave me the impression that I could do whatever I wanted to do, and they taught me how. For example, as soon as my sister and I could drive a car, her with a license and me with a learner’s permit, they filled up the car with gas and set us loose in Florida to go explore! I think we went to Gainesville or over to Orlando or something. Before I got my driver’s license, Dad made sure I knew how to change a tire and check the oil and some other basics. Then the message was, “Go have an adventure!” That was a good start, I think.

Unfolding Awareness

You know, there’s another thing that was probably important in my dawning awareness. I was aware of the Love Canal, just from the news and that kind of thing, and that they were moving people out of a contaminated town. It was in the news. When I was in Ann Arbor, there was a mix-up at a chemical warehouse and they ended up sending this flame retardant to dairy farms all around the state, thinking it was a cattle feed supplement. I was living in Michigan all during that time and millions of people were contaminated with PBBs (polybrominated biphenyls), which is an endocrine disruptor. I think that was one of the things that really prompted me to leave Ann Arbor; I felt contaminated. I felt dirty, I felt scared that I didn’t know what I had been eating.

I made the connection that if we quit buying this stuff, producers will quit making it, and they’ll quit using those chemicals. From small actions can come large results.

It took a long time. It was an unfolding thing. At first, when they said “We’re not going to eat the meat from Michigan anymore,” I was like, “Well, no problem, I’m a vegetarian now.” I did a lot of dairy and cheese, and that ended up being the worst; it was concentrated in the fat. I’ve had endocrine problems that came on as a young adult. Were PBBs the cause? You can’t find the smoking gun with that kind of exposure, but there’s a possibility. They’re still studying it; it’s just one big research project over all those decades.

When something like that happens and you realize that just from one mistake, or one sheer act of stupidity, we all ended up getting this chemical exposure and we don’t know what it’s going to do. I began to be mistrustful of large companies and their chemicals. I think the household hazardous waste interest was, “Well what am I bringing into my home then?” I made the connection that if we quit buying this stuff, producers will quit making it, and they’ll quit using those chemicals. From small actions can come large results.

See also:

Sky Chadde, “Marie Steinwachs, sustainability pioneer, continues work at MU Extension.” Columbia Missourian, October 1, 2013.