Theresa Barry and Labrys Books: Virginia’s First Feminist Bookstore

Interview by Rose Norman, December 5, 2015, updated in 2024

Background

I was born in Washington, D.C., and I lived there the first four years of my life. Then my father moved us to southern Maryland, where I lived with my parents, grandmother, and six brothers until I was 18. Except for four years when I lived in New York and New Jersey while working for The New York Times, I have always lived below the Mason-Dixon line. That includes Maryland and Washington, D.C.

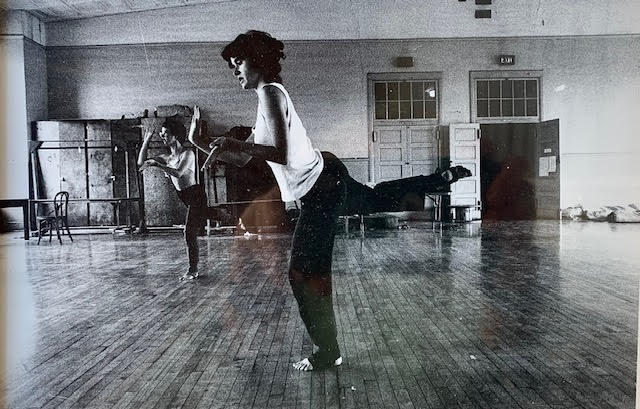

I had a Catholic school education, and then, I went off to Virginia Commonwealth University [in Richmond, Virginia], where I got a Bachelor of Fine Arts in dance and choreography. I was one of the first two graduates of that dance school. I also studied writing through Gotham Writing Workshop online, I taught at Columbia Graduate School of Journalism as an adjunct.

I consider myself to be a lesbian feminist, active to the extent I can be without compromising my position as a journalist. I have always been an artist and writer. I encourage mentoring, coaching writers, and networking relationships with younger journalists.

I had six brothers (one has passed away), and I think that’s enough to get someone started as a feminist. I had a father who preferred boys, by and large, and he made that pretty clear. He was not mean to me in any way. He respected my intelligence. But it did mean I had to fend for myself. I used to go outside to rake all the leaves, or shovel all the snow, or do things I thought could show me off compared to my brothers. Being a girl and other people’s attitudes toward me didn’t dissuade me from doing almost anything.

I learned about community from going to a girls’ summer camp. There I learned that women could do anything they needed to do: chop wood, build a coal fire, cook over a fire, and all these cool things. I learned that I had worth in and of myself, not because I was a girl or a boy. That was especially important once I became a part of a feminist community.

Biographical Note

Born in Washington, D.C., Theresa “Terri” Barry grew up in southern Maryland, in a large Catholic family with six brothers. She was educated in Catholic schools.

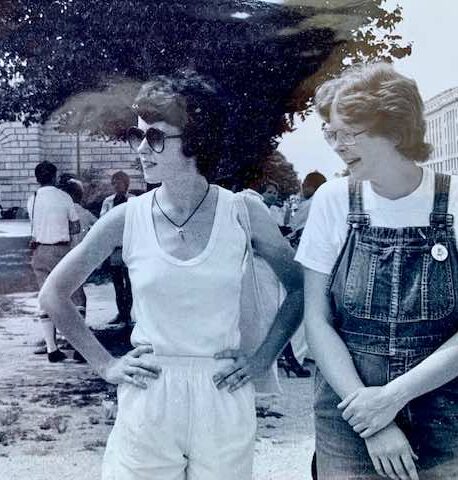

Terri came out as a lesbian in 1976 while working in Michigan. She met her partner, Joan Mayfield, months later when she returned to Richmond, Virginia. From 1977 to approximatey 1980, she and Joan opened and ran Labrys Books in the living room of their Richmond home.

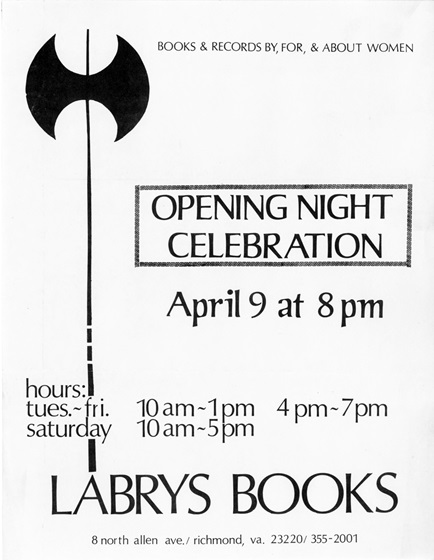

They chose the name Labrys, after the double headed ritual axe found in ancient Minoan depictions of the Mother Goddess. The bookstore was run with the support of the Richmond Lesbian Feminists, an organization that still exists today. Both Terri Barry and Joan Mayfield helped publish the newsletter for the Richmond Lesbian Feminists every month.

That didn’t happen until about 1976, when I was 24. I came out as a lesbian that year, and I met my first feminists. It might have been 1977 when I went with Beth Marschak to a Virginia Women’s Political Caucus meeting at a women’s college. You know how you look around and pick out people you might like to talk to later? I picked out five or six people who looked fairly interesting to me. At some point, a woman stood up, saying she thought it was important that everybody who identified as lesbians should stand up. Damned if all of those people I’d noticed didn’t stand up! [laughter] A big old light bulb went off.

A little later, I went back to my friends who were lesbians and asked why they didn’t tell me that they knew I was a lesbian. They said that at the time I was way too young to handle that information. I gradually grew into those friendships.

This was the 1970s, and we were making art, making music, and certainly not focused on career. The people I hung out with, if they weren’t politically active, they were artists or musicians, thinking about the next thing they were going to work on and the people they’d work with. A career seemed pretty remote. Even so, once I did graduate, I moved up to Washington, D.C. to be with a new partner.

Labrys Books

In 1977, I got actively involved in Virginia with Richmond Lesbian Feminists, which published a newsletter and sponsored dances, softball, and soccer pickup games. At about that time I met my partner, Joan Mayfield, who was also living in Richmond. Joan and I both had a passion for books. We thought that a bookstore, especially a women’s bookstore, would be a natural fit.

We decided to go on a cross-country trip. The goal of this would be, other than having a good time, to visit coast to coast women’s bookstores and rock shops because we both were into collecting rocks . We went to Minneapolis, Minnesota; Ann Arbor, Michigan; San Francisco, California. I know there must have been a women’s bookstore in Seattle. We visited five or six bookstores, with an eye to where they were located, how much it took to get the bookstore started, what their place in the community was, and anything they thought they could teach us because we knew nothing. Neither of us had run a business before although we had experience in retail. We paid a visit to the Small Business Administration. When we came back, we thought we kind of had what we needed to get started. We didn’t exactly, but we adapted.

We called it Labrys Books after the double-headed axe, from some historical research we had done. It was kind of an unfortunate choice in some ways. People kept misreading it to say Larry’s Books! [laughter] We were so focused on our core group that it didn’t occur to us that people are thinking differently from us.

We started taking the bookstore with us just about everywhere. If there was a conference, we were there. If there were workshops, we would teach some of them. I started teaching things at sci-fi workshops, sci-fi by women. Joan knew about mysteries. If there was some other workshop they needed, we’d figure it out and teach it. We would throw those fifty-pound boxes of books in the car and head out to the next one. We met some cool people. We also met people that grew to be friends, like Laurie Fuchs of Ladyslipper [Durham, North Carolina]. There’s a whole chain of the lesbian community that runs from Washington, D.C. to Durham and further on. We met Mary Farmer, who owned Lammas Books in Washington D.C.

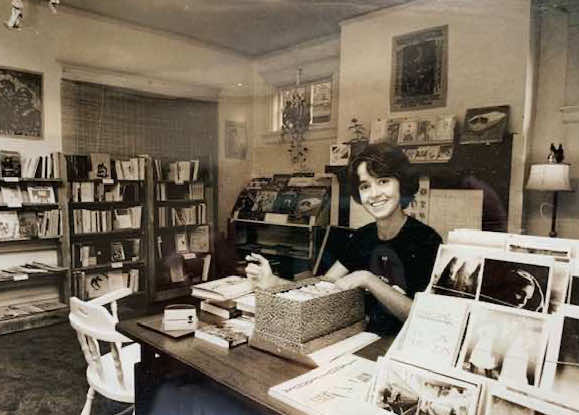

Since the house I owned was zoned commercial and residential, we were able to open the bookstore in a place that would not cost us anything. That was important to us at the time. People came, but not in the droves we had hoped. There were readers, but not enough readers. So, we did not do well. We had to have other jobs at the same time. We did readings at the store, had a book group. Anything anybody wanted to do, we would try to host so as to bring people into the bookstore. None of this was saying that we didn’t enjoy participating in all of this. We got as much enjoyment out of it as anybody, but our bottom line wasn’t improving.

We were very optimistic. We were hugely undercapitalized to the extent that we didn’t learn everything we needed from other women’s bookstores although they really did help us a lot. We not only didn’t know what we were doing, but we didn’t realize some important things, such as: we needed to be in a higher traffic area. If there had been online sales then, that would have helped. I didn’t know there was a Feminist Bookstore Network. At least I don’t think I did. We knew those other women who owned bookstores, and some of the women running publishing houses. We had both worked in retail, so we weren’t totally ignorant. But running a bookstore and working for it is a whole different story.

I think our choice of inventory was good. It turned out I was good at selling books. I could sell anybody anything if I could just get them in there. Joan was good at a whole lot of the business, including selling. She and I were complementary in style. She was good at the practical decisions and bookkeeping. Joan built the bookshelves. She was a sculptor, and building things was a strong suit. We got along well. It was pretty much an equal effort at every level. We made all decisions together.

Eventually, having the business in the house and not being able to talk about anything else took a toll on the relationship. There was a breakdown between us, and Joan went to Durham, North Carolina. I guess the bookstore kept going for a while. It didn’t work out for her in Durham, and she moved back to Richmond. We lived together as friends. At some point, we passed the bookstore over to the next iteration, which Beth Marschak can tell you more about. [Marschak says that it was 1981 when she and others opened WomensBooks, organized as a co-op. It lasted until 1993.] By 1980, I had started spending summers up in Washington, D.C., so I would have missed some of that. It was a strange time.

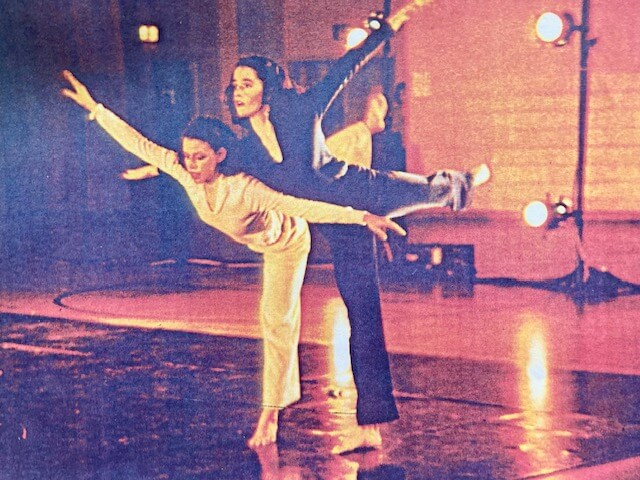

Between 1980 and 1982, I was going full-time back to school. The dance school came to me to sat that they were starting a dance department. They asked if I wanted to be one of the first two people to graduate. I said yes, and two years later I had a dance degree, after twelve years total at Virginia Commonwealth University. I wasn’t really fussed about the degree thing, but it turned out to be a good career move to have one.

On Being Southern and Living in the South

I have always lived below the Mason-Dixon line, which includes both Maryland and the District of Columbia. I would not have considered Maryland to be really Southern until I was older, learning more of its history and the Civil War and Maryland: Harriet Tubman having grown up on the Eastern Shore, Frederick Douglass having been born there, John Wilkes Booth having to flee Washington right past where I lived, and go on down to the river. At the time, it didn’t seem to have a real Southern identity to me; however yes, I think I grew up in the South.

“Who are your people?” That was new to me. Once I was in the lesbian-feminist community,

I could say who my people were.

Living in Richmond 1970 to 1982, I was thrilled to be in a place with an identity as the South. Here’s one of the reasons. I felt as though I was much more on the front lines when it came to sexism and racism. People would just say what they had to say. They didn’t pretend that they weren’t sexist or racist. They just came out with it. My favorite anecdote about this is from when I worked at the Richmond Times Dispatch. I was standing at the elevator, and here came a city editor, a guy full of bluff and bluster, holding a lot of boxes in his arms. I said to him, “Go ahead, Earl.” And he looked at me and said, “Don’t give me any of that women’s lib shit!” [laughter]. I got on the elevator and said, “Why Earl, how chivalrous of you!” He didn’t like that either.

You had a chance to talk to people, say what you believed, and hear what they believed. Everybody got to see each other as a human being. I thought it was great. I know that’s an odd thing to be happy about, yet I was. I also loved the fact that in the South, the first thing people asked was, “Who are your people?” That was new to me. Once I was in the lesbian-feminist community, I could say who my people were. I had a place in society that I didn’t feel I had before when I was living in Maryland, and it stuck with me.

On Being a Lesbian-Feminist Activist and Artist

I do think of myself as a lesbian-feminist activist and as an artist. I got to be an artist the whole twelve years I was in college. I didn’t graduate until the end of that because I was having way too much fun. There was a lot of studio time. I was making photographs, and I was part of a dance company. That went on through 1982. I think I’ve always been a feminist, but I just didn’t say that word out loud until probably 1976. Once there was a word that I could attach to what it was that I believed, that was much better for me. There was a community that I could support and be supported by. Joan and I both went to an early Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, which was a revelation.

As far as being politically active, I don’t have a lot of specifics in my head. I was in the march on Washington for equal rights [National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, 1979]. I cut off my hair for that. That seemed to kind of make the statement for me. For the most part, I didn’t speak to my family about this business of being a lesbian. Later, they liked to tell me they already knew (and of course they didn’t).

My father, who worked for a national intelligence agency, did know what I was up to. He would call me on a few occasions when protests occurred. These weren’t in the Washington papers, and I wondered how he knew about these protests. Turns out, the FBI used to keep him apprised of some of my actions. I’m sure I wasn’t their focus. I was nowhere near that important; but he did get their alerts. When I was getting ready to open the bookstore, he called me and asked, “Are you sure you know what you’re doing?” I knew he didn’t mean did I know how to run a business, but was I willing to pay the consequences if there were any. If you grow up with a man whose career went through the McCarthy era, you know what he’s talking about. Are you willing to deal with any political or job or life consequences? He didn’t ask if I wanted to go to jail, and yet I’m sure that was in there somewhere.

If I want to go to a protest, I think about how that might affect my job. Am I willing to go to jail?

As a result, most of my adult life, I do consider those things. If I want to go to a protest, I think about how that might affect my job. Am I willing to go to jail? Am I willing to have my face published somewhere? (Not that it happened.) Am I willing to take the consequences of my actions? I always decide yes before I go. Then, I’m at peace with what I’m doing. It’s a very considered kind of activism.

Somebody you probably want to talk to is Colevia Carter. I moved to Washington, D.C. in 1982 to begin a long relationship with her. She’s very active and vital on her own merits in the lesbian, gay, bi, transsexual community, and has been ever since I’ve known her.

Once I got up here, I lucked into a job with USA Today, before it opened, which made me one of the founders. As a result of becoming a journalist, I realized I was going to have to tone down the political stuff. I looked at what we were doing that I could continue. That was to work with health care. I became active, along with my partner, at Whitman-Walker, a clinic that served the needs of the gay community, and still does. I was on their AIDS hotline, explaining prevention, causes, and behaviors, whatever it was that people needed. We went on to work with Damien Ministries, who was serving women with AIDS.

Dance and Writing

I joined a second dance company when I moved to D.C., and we were putting on concerts, but then I had an injury, a ruptured disc in my neck, along with carpal tunnel. After a series of injuries, one of which I had surgery for, I decided my body was saying that’s enough. So, I stopped working with choreography. I did keep on with writing. I’ve been writing since I was a kid. In fact, I found a letter I wrote to Sinister Wisdom when I was looking for the bookstore stuff that I couldn’t find. That was in August of 1980. I sent them about ten poems, and they published at least one, “Black Against a Clear Sky.” That was one of the nicest things that has happened to me. Everything else I’ve published has been self-published. I’ve moved on from poetry, and just do fiction now. My business card says “artist/journalist” because I never did choose. I wasn’t going to put “activist” on a card as long as I was a journalist.

From Sinister Wisdom volume 24 (1983), 67-68.

Activism in the 1980s and 90s

During the ‘80s and ‘90s, I kept up with my political work with Whitman-Walker [a community health care center in D.C., with a special expertise in LGBTQ+ and HIV care]. I was a founding member of Best Friends, a group for Black gay men. All of the members were friends of mine and of my then-partner Colevia. The goal was to make sure that their care was the equivalent to what white gay men were getting. I also wrote a grant about women and AIDS for NIDA [National Institute on Drug Abuse] with my partner. In 1988, I helped edit the AIDS Sourcebook, when I was working for USA Today. I kept on mentoring relationships and things like that.

Working in Journalism

I’m a very nosy person who likes to swear, so working at a newspaper was a great fit. At least we weren’t drinking in the newsroom at USA Today (they sure did in old newsrooms). It was fascinating stuff, being at the beginning of a business, and they were throwing a lot of money at it. It was just an exciting-to-be-at newspaper. I did not feel so bad about not staying with dance. It seemed to me that things were beginning to break down body-wise, and I might as well find something else to do

I know some journalists who are such purists that they don’t even vote. I call them journalism priests and nuns. I don’t go that far. In fact, I feel that journalists who can express a considered opinion are the ones best able to filter their opinion out of their work to give people a balanced approach. I do vote, and I do stuff in the newsroom when there’s an opportunity to balance out possible bias.

There are a lot of politics in a newsroom, of course, and there can be bias in choices. I will say one thing for USA Today. I have never in my life worked in a newsroom as diverse as the ones at USA Today. It was a top-down choice. Al Neuharth, whatever people say about him, insisted that the newsroom include Black journalists, Hispanic journalists, different ages of journalists, and that a woman be on the front page every day. There was a lot of resistance to that. We had Brooke Shields on the front page an awful lot.

Neuharth also insisted that women athletes be covered in the sports section. Racial diversity was a real plus of working at USA Today. I was exposed to a very broad community that I learned a lot from and that I was happy to have near me. Their discussion of issues meant it would be much broader in the paper. It was a great paper. USA Today was a grand experiment. Some of the changes that it inspired were not such bad things. I’m not such an old school journalist as I might be.

After USA Today, I worked for a Gannett Wire Service in the same building. Then I worked on books for a while. Then I went back to USA Today. This whole time I was working, I finally decided I was going to keep my head down and work as hard as I could. I figured that would get me somewhere someday. Sure enough, one day I got a call from a former colleague who wanted to know if I wanted him to put my name in to The New York Times. They brought me in on trial, and hired me. I asked why they wanted to hire me, and the person said I was assertive or aggressive in my editing and paid attention to details. These were things I was proud of. I thought if they don’t mind my being the kind of editor I am, then sure, let’s do this.

I moved to New York for four years. I lived in New Jersey for most of that. When I was there, I didn’t do any activism. I worked sometimes sixty hours a week, and I taught sometimes as an adjunct in the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. The rest of the time I took online writing classes. I was pretty busy.

At the end of the four years, it was clear that my parents were getting older enough that I needed to be around them again, so I moved back to Washington, D.C. Bloomberg News hired me, and I worked there for nine years, during which my parents became ill and died. After my parents died, everything stopped. It was a lot to take in, and it had been a long struggle with the medical establishment. I’m not trying to say I did the whole thing, because my brothers were there, too.

I left Bloomberg and went to a smaller news publication. Eventually I landed where I am now, in northern Virginia, at a publisher of regulatory newsletters.

This interview was edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. More recently, it was edited and updated for posting on this website. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.