Sonja Franeta: Writer, Translator, Educator, and Socialist Workers Party Candidate for Mayor of Birmingham, Alabama

Interview by Silk Jazmyne Hindus, May 16, 2023

Growing Up Working Class in the Bronx

Silk Jazmyne Hindus: This is Silk Jazmyne interviewing Sonja Franeta for the Southern Lesbian Feminist Activist Herstory Project. Let’s start with where you grew up and where you were educated.

Sonja Franeta: I grew up in the Bronx in New York, in an immigrant family. My parents were superintendents of the building we lived in. In exchange, we got free rent. We lived in the basement of this building.

I went to Catholic school, which was only two blocks away. I went there for twelve years, actually. And then I went to NYU [New York University], because my entire family worked there. They weren’t intellectuals or anything. My father was a maintenance mechanic, my uncle worked in the carpentry shop, and my grandfather was the head of the carpentry shop.

I chose to go to NYU where I got a scholarship and a work-study grant. At that time, you know, NYU uptown was very close to my house. You don’t think of NYU as being connected to people from the old country, from old Europe or something. It was part of my neighborhood, interestingly enough. My mother worked in the university library. She shelved the books and stuff like that, as the student workers do, since she was one of the staff. I used to go see her sometimes between classes and such. I majored in English and minored in Russian.

University and Moving to California

SJH: You did say that you are from the Bronx, New York. Do you identify as Southern now? If you don’t, then how did you end up in the South?

SF: At NYU, I worked in the Physics Department. I started going out with one of the professors. I wasn’t very interested in getting married, but I wanted to leave my family, and that seemed like the only way. We got married in 1971. For two years, we lived in the Village [Greenwich Village, in Manhattan, where NYU is].

Then, Tom got a job at Stanford Research Institute, and we moved to California. That was in approximately 1974. I went to graduate school at UC Berkeley [The University of California in Berkeley, California]. I wanted to get a PhD. However, they didn’t want me because I was not very articulate or something. I don’t know what it was. I didn’t fit in. I passed my “permission to proceed,” that is, the written part. But when it came to speaking in front of a group of people, the committee, those five professors who were questioning me, it was awful! I just froze. I tried once again, and the same thing happened. And I failed again. They didn’t let me go on for my PhD. Can you believe it? Because I got tongue-tied.

Biographical Note

Sonja Franeta is a writer, translator, educator, and activist born in the Bronx, New York, in 1952 to an immigrant Yugoslav family. She received a master’s degree in Russian from New York University and a master’s degree in comparative literature from the University of California, Berkeley.

She came out as a lesbian while on a trip to the Soviet Union in 1977. When she returned to the San Francisco Bay Area she joined the Socialist Workers Party. She was an activist in the women’s movement, as well as in other movements for social change.In 1980, Sonja moved to Birmingham, Alabama, to work in industry and to do union activism. She worked as a journeyman machinist. She ran for mayor of Birmingham as a socialist candidate in 1983.

After Sonja left the Socialist Workers Party in 1990, she went to Russia to work with LGBT people and as a coordinator for Wheeled Mobility Center’s wheelchair project in Novosibirsk.

(Read full bio.)

Moving to Alabama to do Socialist Workers Party Work

SJH: What year did you move to the South?

SF: I moved to the South in 1980. I had left my husband. I had come out as a lesbian in Russia, actually, on a trip to Russia.

What had happened was that my husband got a research position at the University of Birmingham in Birmingham, England. I was translating a book from Russian to English for publication. I was visiting London one day, which was a short train ride. I passed a neighborhood bookstore, where I saw a small ad taped on the window. This ad was asking for a few more people to join a group of socialists and communists going to the Soviet Union. I decided to go. It was only for two weeks. We went to three cities: Moscow and Leningrad; and to Tallinn in Estonia.

On this trip, I met my first love. She was an American woman backpacking through Europe. She had seen the same ad, joining the group of “UKers” [people from the United Kingdom]. I had been thinking about women for a while. I could not figure out how to meet lesbians, even in the San Francisco Bay Area. My husband was aware of my sexual attraction for women. Anyway, when I met Gina, I started talking with her. I had such a physical reaction, such an attraction, that when she asked me innocently if I ever feel attracted to women, I couldn’t speak. Tears came to my eyes.

We first kissed in Lenin Hills Park, and we first made love in a Moscow hotel. When I came home, I told my husband. I knew my life had changed irrevocably. He was patient because he didn’t think I would actually leave him. He thought that this was a side thing. But I had come out as a lesbian. When we came back to California, I moved to San Francisco, and my new life as a lesbian began.

I connected with Gina politically. She was a socialist, and she introduced me to her party when we were both together in San Francisco. I became a socialist and joined the Socialist Workers Party.

I was in the party for a while. I was doing a lot of political work in San Francisco, activism for women’s rights, you know, to stop the intervention of the U.S. in Latin America. Civil Rights and antiwar work. I was involved in all of that.

In 1980, my youngest sister died in a car wreck in New York. It was a big tragedy, and it was terrible. After I got back from the funeral, I remember listening to a speech given by one of the party leaders saying that it would be great if we got involved in the coal miners’ union, UMWA [United Mine Workers of America].

There were big fights coming up, big struggles, and we wanted to be part of this. One of the places that they were focusing on getting people into the mines was in Birmingham, Alabama. There’s a huge coal mining industry there. I decided to go. Part of it was wanting to move, and part was to do something very passionate. Also, I went to Birmingham because I knew some people there, some comrades. I had met some people who were in the party there, and we were very good friends. They helped me a lot to get oriented. I moved there in 1980.

The people in the branch were from different places, a few from Birmingham. The branch had existed for a number of years, and people were very active in the civil rights work and the mines already. Just like in most other cities, we worked out of a bookstore, selling mostly Pathfinder Books, the Socialist Workers Party imprint. We would also bring titles out to put on tables to sell at events.

Activism with the National Organization for Women (NOW)

SJH: In what ways were you active in the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s?

SF: I was very active in NOW, the National Organization for Women, in San Francisco. I even went to their conventions. I was very active in that, and I learned a lot about how lesbians were pushed out of the “scene.” You know, they weren’t really included. And they were shut down, especially if they brought up lesbian issues or identified as lesbian. There also weren’t very many Black women, or Latina women, involved in NOW. That was another one of my concerns. I didn’t understand why they weren’t trying to get more people of color involved. I was involved in all those things, too, the lesbians and recruiting women of color.

Sonja Franeta’s Slavic Ethnicity

SJH: I’m glad that you brought up other marginalized groups. What is your ethnicity? You mentioned going to Russia, and I know a lot about you since I know you personally. For the sake of this interview, how do you identify ethnically?

SF: My parents were both from the former Yugoslavia. When I was growing up, I didn’t know any English when I started school. I just knew Serbo-Croatian. That was really my first language. It was very strong culturally in my youth, the ethnic Croatian, you know. In Astoria [in Queens, New York], there was a Croatian Club. We used to go to dances there.

Ethnically, I thought of myself as Yugoslavian. When I was in college, I tried to look for Serbo-Croatian classes to study the language. I started studying Russian, which is closely related, and I became very interested in Russian literature.

SJH: How many languages do you speak now? What are the languages that you have spoken in your lifetime besides Serbo-Croatian and Russian?

SF: French. I studied French in college, which I really enjoyed. And Spanish. I’m studying Spanish now. I’m getting pretty good at it. I am fluent in Russian because of my education and work. I wish I could be more fluent in Croatian.

SJH: How have your ethnicity and language influenced your worldview?

SF: Oh, that’s a really good question. I think that I’ve always been interested in other cultures and in languages. I do think the languages helped me get interested in other cultures. I’ve always wanted to connect with other cultures, other ethnicities, yes. Also, maybe it was the influence of both of my parents, who were very interested in other cultures. They talked a lot about their cultures with each other. My father was a Serb, and my mother was Croatian. We were very open to other people when we were growing up. My parents had friends, people from different cultures all the time. My father would bring home people he met. For example, this Dominican guy. I don’t know where he met him. It was not very common in our neighborhood for people to mix, you know, colorwise. No matter. My father brought him home, and sometimes, this guy would have supper with us, or work with my father.

Linking Socialist Workers Party to Lesbian Feminist Activism

SJH: How did you get involved with the Socialist Workers Party in San Francisco?

SF: When I met my first girlfriend, she actually turned me on to all this, really. We would talk about a lot of the things that I had been thinking over the past couple of years. I would say, as for women, I mean, I was very, very sheltered, you could say, by my marriage. I didn’t really interact with any kind of activists or anything like that. But I was drawn to the women’s movement. I was drawn to the antiwar movement and the civil rights movement. I was drawn to all of these things, wanting to know more about them, and I read about them. I never really did anything until I met her.

She basically supported me in my thinking, you know, and she said “Yes, and why didn’t they want you in that PhD program? Because you were working class.” And that was really true. There was even a conversation that the head of my committee had with me, right before one of my exam things. He had asked me, “So, what did your father do for a living?” I said, “He was a maintenance mechanic and a locksmith.” He said, “Oh,” almost as if he were fishing around to figure out why I didn’t belong, you know, in this PhD level. Gina was right. I really felt that she was right, and that I was being filtered out.

She got me excited about a lot of these political ideas that I was already having, about women and racism and war. She would talk to me about the Socialist Workers Party and socialist ideas. I didn’t join right away, but I joined the San Francisco chapter of NOW [National Organization for Women], and I did a lot of work with the women’s movement. I loved sitting on those tables, and trying to petition for this and that, giving out brochures. I loved talking to people. Then, when I became part of the party, I was so amazed at how people were interested in my ideas. I mean, I was amazed at myself, getting up in front of a group of people, because I was pretty shy. I would say what I thought, and when I would get support, I thought, wow, this is really validating! I was acquiring my own voice.

Starting Lesbians WriteOn in 2021

SJH: Tell me more about Lesbians WriteOn and how that started.

SF: This is a long time after that. I’m not a part of the Socialist Workers Party any longer. I left the party in 1990 in San Francisco. I wanted to have time for my writing, and for my own thoughts. Not to have to be pushing myself to be an activist all the time. I never stopped being an activist.

When I moved to Florida, eight years ago, I was really impressed that ReadOut was happening in the little town of Gulfport, near St. Petersburg. This was a lesbian literature event happening once a year. [ReadOut has now become an LGBTQ event.] I got involved in that, almost from the beginning. Then we had a disagreement in that group. Several of us had a problem with one of the organizers, and the way that they were conducting the group. We were also organizers, but she was the head of the Library board. We were told to leave. Our group of six formed our own organization: Lesbians WriteOn.

That was just two years ago, in the autumn of 2021. We started in October putting on our events, basically weekly workshops, presentations by lesbian writers. It was a safe place, an opportunity for lesbians to get together and to read their work. It’s been a really wonderful space for lesbians to say what they think, and it’s a safe space.

SJH: Definitely safe space. Do you regularly partner with other organizations who have events?

SF: Partner for events? We tried to, but we haven’t really been able to partner with other organizations. We do partner with other individuals, yes.

SJH: Has this new group been pretty much even keel since the beginning?

SF: It’s been pretty much the same since the beginning. I really have grown to appreciate the other women who are organizing Lesbians WriteOn. Also, many of the people who come regularly. The number of attendees has grown. It’s been a community. It has become a community. And it’s really wonderful.

Civil Rights Issues in Birmingham

SJH: Can you tell me a little bit more about your involvement with the civil rights movement?

SF: When I came to Birmingham, I really loved it. It’s a beautiful place, a beautiful city, and Alabama is beautiful. It was 1980. I lived in a house with another woman, and there were other apartments in the house. It was on a hill, and there were trees everywhere. It’s a city with a lot of trees. I learned a lot, looking for a job in the mines for one thing, and about the industry, and the area there, and some of the ways people are with each other, like the separation of African Americans and white people. The separation was incredible. I worked in a military airplane repair place, which was one of the biggest employers of Birmingham. I remember meeting this one guy. He was kind of reluctant to say it, but he said that his wife was Mexican. And I said, “Why would you be reluctant to say it?” He said, “Well, you know, there’s a lot of prejudice here.” He was a white guy.

There was such prejudice, there was such a separation. I had never seen such a thing. And I did do a lot of work in the union to try to counteract that, of course. One of the things we did was that we were very active in the anti-apartheid movement. We tried to bring that into the union, and to get the union to support the boycott of South Africa. We got such a name for ourselves, you know, in the union.

Not only that, but there were little skirmishes in the union that involved some of the Black workers. For example, the area that was the absolute worst part of the whole place was the cleaning area. The workers would clean the outside of military planes with this harsh chemical. I don’t even know what it was, but it stunk to high heaven. The only people who worked there were Black people, mostly Black women. This work area was right next to the machine shop where I worked, and also, it was next to the women’s bathroom. I’d go in the bathroom, and they would be throwing up or they would be sick. It would be so crowded with women trying to get out of that mess to be in the bathroom for a while to rest from it. I mean, that was the only way they could rest from that smell.

I’m going on about this, I know, but that was one of the places where I did some political work, among those women. We talked a lot, talked about politics, you know, and they appreciated me. There were many instances like that, where I would make friends with some of the Black workers, and it would be very much observed in the plant. One of the men that I worked with in the shop made a remark about how the Black coworkers stick together and help each other out. He said, “I never saw no white people sticking up for them except for you people.” By “you people,” he meant me and the other socialists in the plant. These problems of how people were treated at work or how they were penalized for not doing something, often it was dangerous. Stuff like that.

Running for Mayor of Birmingham

SJH: “What’s going on there?”

SF: “What’s going on?” I did run for mayor of Birmingham.

SJH: Yay! That’s a big deal!

SF: It was 1983, and I had been in that workplace for a couple of years already. The party said to me, “You know, you’re in a very good position. We want to run somebody for mayor. It’s going to be a big campaign, and we’d like you to be the Socialist Workers Party candidate.” I said, “Oh, no, really?” They said, “Yes, yes!” I was convinced to do it, knowing that I’d have a lot of help.

So, I ran for mayor, and it was a fascinating campaign. At work, suddenly other people who were known to be in the party would find these nooses at their machines, as threats. Can you believe that? One day I came in, and there was a fake penis at my machine. It had steel shavings as pubic hair on the penis. And it was right in my toolbox. I said “Yuck!” and I took it, and I threw it in the trash, you know, demonstratively. We talked to some people about it, and people were really upset.

Some of the white workers, the union people, said, “Really, you have every right to run for office. You have every right to talk about your politics. Why should they do that to you?” As soon as we reported the threats to the union and made it known, the threats stopped. It was a very interesting campaign. A couple of times I was prevented from participating in debates. I did participate in several debates, official ones, even on television.

SJH: There’s probably an archive where we could go find that footage of your debates.

SF: It was really fun. Many of the women in the other parts of the plant would come over to visit me at the machine shop. They said, “I’m going to vote for you because it feels so great to vote for a woman.”And we did get to say a lot about our politics. That was the reason that we ran people for candidates. The Socialist Workers Party got to have a forum, a platform for our politics, and to explain to people some of these ideas, to show that there is something besides the two-party system.

Art and Activism

SJH: Right. I think that’s definitely necessary. You have such an extensive history of activism. At this point in time, have you had involvement in present-day liberation movements, like recently protesting? Do you think of your art as your activism?

SF: I do still go out to demonstrations. I have gone to a number of demonstrations in St. Petersburg [Florida]. I did want to mention one other part of my activism that is really important for me, and that is the LGBTQ activism in Russia, which really was invaluable to those people.

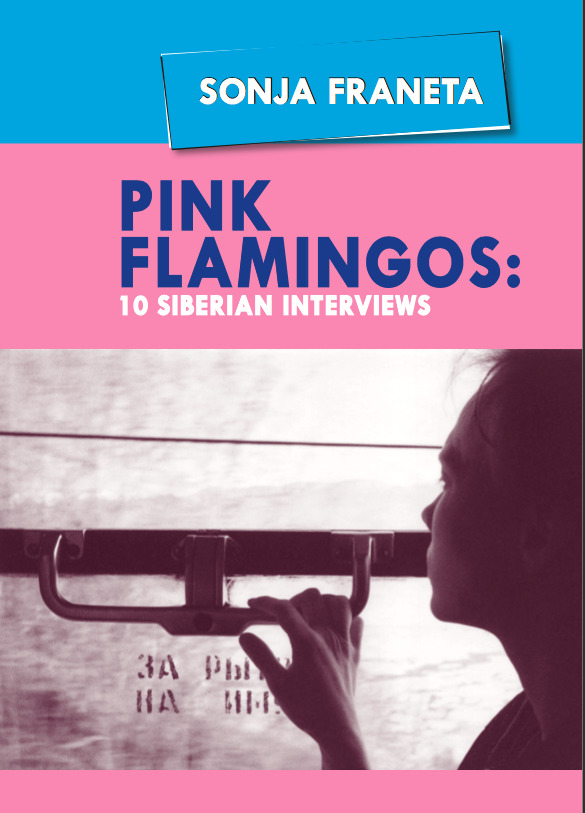

When I published my book Pink Flamingos: Ten Siberian Interviews, I did interviews with gays and lesbians in Russia. When I heard what some of the activists there said about me, I was really touched. They saw me as one of them, as an activist like them. And that is what I did when I went to Russia in the 1990s. I helped them with speaking, with writing about things, with interviews. I did a lot of work in the ‘90s to help the gays and lesbians in Russia to be more public about their rights. And even when they were too hesitant to get on TV or be more public, I did it for them. I spoke Russian well enough that I could even be on a Russian talk show.

SJH: I remember that for Lesbians WriteOn, for International Women’s Day, how you featured the Russian poet. You translated for her so that we could all understand. That was amazing, for sure.

SF: I’m still doing that now, continuing to connect with Ukrainian and Russian gays and lesbians.

SJH: Absolutely, yes, because we need it. We need to hear those stories and hear what’s coming out of there. Is there anything else to add about your history of activism or your history of feminism?

SF: I also want to mention that some friends from Argentina and I did some work together around lesbian activism. You mentioned this thing about art. I do think that art can be a form of activism. And I think I’m doing that in my writing today. I’m finishing a novel, an activist novel, trying to show women who had to leave the United States for being lesbians, in order to be themselves, and how they found themselves in Russia where there was also repression of lesbians. There’s this whole explanation that happens in the book, besides it being a story. I think that some of the writing today that’s really wonderful is activist writing. Right now, Black women are getting published and being activists in their writing. It’s happening. It’s a great time for arts and activism.

SJH: Right, and trying to keep access to those books since obviously, in the state of Florida, where we’re dealing with book bans and things of that sort, we need to keep them going. Thank you so much for this time.

This interview has been edited for archiving by the interviewer and interviewee, close to the time of the interview. Original interviews are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

See also:

Sonja Franeta, “My Birmingham,” unpublished memoir.

My Pink Road to Russia: Tales of Amazons, Peasants, and Queers. Dacha Books, 2015.

Sonja Franeta, Pink Flamingos: 10 Siberian Interviews. Dacha Books, 2017.